Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Development of Mycelium Leather (Mylea) from Oil Palm Empty Fruit Bunch (OPEFB) Waste Using White Rot Fungi as a Renewable Leather Material

1 School of Life Sciences and Technology, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Jalan Ganesha No. 10, Bandung, 40132, Indonesia

2 Department of Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Industrial Technology, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Bandung, 40132, Indonesia

3 Research Center for Biomass and Bioproducts, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), JI Raya Bogor KM 46, Cibinong, 16911, Indonesia

* Corresponding Author: Rudi Dungani. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2026, 14(1), 5 https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0113

Received 13 June 2025; Accepted 12 August 2025; Issue published 23 January 2026

Abstract

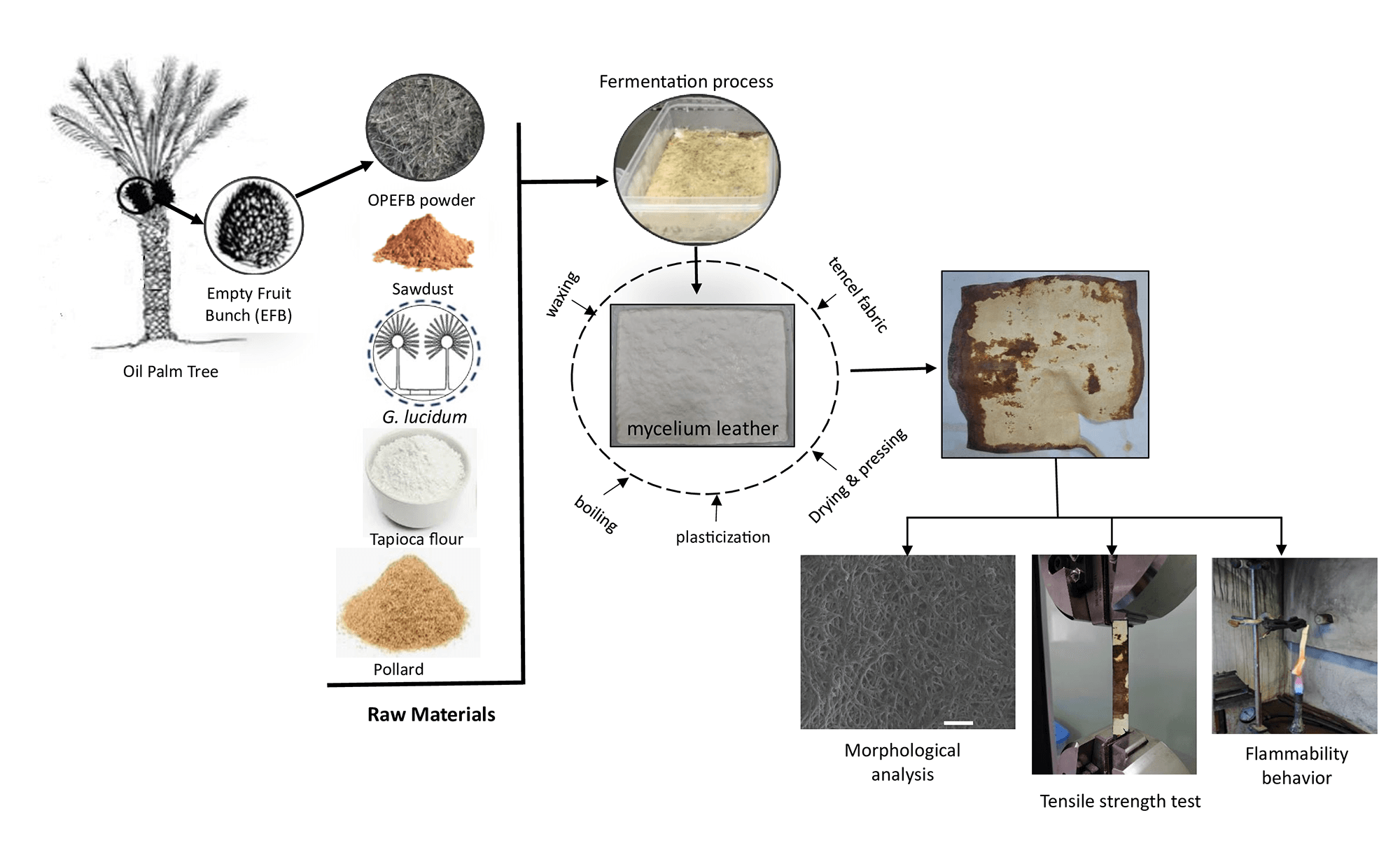

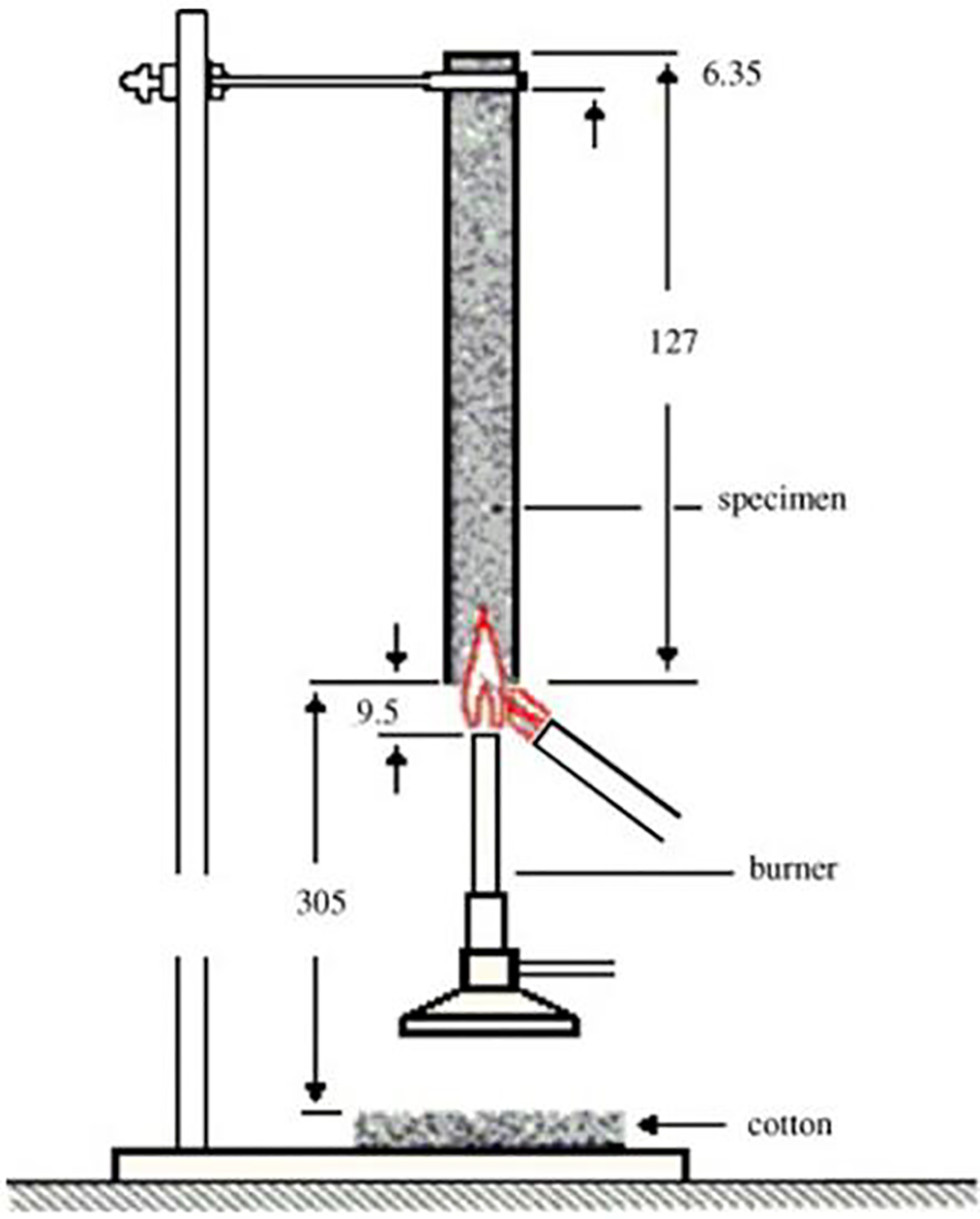

This study aimed to produce and characterize mycelium leather (Mylea) derived from oil palm empty fruit bunch (OPEFB). Variations in OPEFB composition (10%, 20%, 30%, and 40%) were tested using a 10% w/w Ganoderma lucidum inoculum. The mycelium underwent boiling, plasticization, drying, pressing, waxing, and Tencel fabric reinforcement to form Mylea. The physical, mechanical, and flammability properties of OPEFB-based Mylea were evaluated as a potential animal leather substitute. The highest tensile strength (8.47 MPa) was observed in the 0% OPEFB sample due to reinforcement with the Tencel fabric layer. Meanwhile, the 20% OPEFB sample after drying exhibited a tensile strength of 5.78 MPa and a lower elastic modulus (14.48 MPa), indicating increased flexibility but reduced stiffness. Among the tested compositions, 20% OPEFB provided the best balance between growth time and material quality. Flammability tests showed that Mylea with 20% OPEFB had a longer burn time (43.5 ± 7.78 s) compared to 0% OPEFB (21.0 ± 1.41 s). However, the addition of OPEFB did not improve fire resistance, as none of the samples met UL 94 V-0, V-1, or V-2 standards.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Over the past twenty years, a global movement has emerged focused on advancing and employing more sustainable materials and technologies for the production of industrial and technological goods [1]. Renewable resources, such as mycelium-based materials, exhibit positive effects, including reduced embodied energies and increased energy efficiencies [2,3]. Mycelium-based materials, either on their own or as composites, are created by cultivating the vegetative component of mushroom-producing fungi on various organic substrates. This growth can occur both on the substrate’s surface and within it [4]. In some cases, the fungi extend beyond the substrate, forming a dense or soft layer known as fungal skin. Mycelium-based materials find potential application in different fields, including paper [5], biomedical [6], packaging [7], films [8], textile [9], cosmetic [10], bricks and panels [11], construction industry [12], noise reduction [13], thermal degradation resistance [14] and imitation leather [15–17].

Furthermore, the use of mycelium in composite production aligns with the growing demand for sustainable materials derived from renewable resources [18]. The filamentous part of a fungus is the mycelium on an organic substrate, which results in the development of fascinating biocomposite with a wide range of properties and applications such as mycelium leather (mylea). Mylea from mushroom mycelium, which is an environmentally friendly alternative to animal and synthetic leather. Fungi and agro-residue such as oil palm empty fruit bunch (OPEFB) are the most suitable combinations for future mylea development. The organism (fungal species) has been identified as one of the factors that determine the properties of the mycelium [19]. It was reported that the activity of Trametes multicolor on rapeseed straw results in a smooth and foam-like structure whereas the colonization of P. ostreatus on the same substrate (rapeseed straw) produced mycelium with rough structure [20]. However, the white rots saprotrophs species of fungi were noted to exhibit good substrate colonization rate, have strong mycorrhizal, endophytic, or pathogenic character, and are most efficient in digesting plant cell wall material (lignocellulose) due to secretion of ligninolytic enzymes [20].

Early studies on mycelium materials were primarily focused on their applications in packaging and insulation [21]. However, recent advancements in fungal biotechnology, substrate optimization, and biofabrication techniques have expanded the scope of research into flexible composites suitable for textiles and consumer products. Notably, studies have explored the effects of fungal species (e.g., Ganoderma lucidum, Pleurotus ostreatus) [22,23], substrate composition [24], and environmental growth conditions [25] on the morphology, density, and mechanical properties of the resulting mycelium leather. Concurrently, post-processing methods such as plasticization, drying, pressing, coating, and reinforcement (e.g., with fabrics or natural waxes) have become central to improving the functional characteristics of mycelium leather-such as durability, water resistance, and flame retardancy-enabling comparisons with conventional materials like polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyurethane (PU), and animal hides.

The empty fruit bunch (EFB) is classified as a lignocellulosic compound, which contains cellulose and hemicellulose as well as polysaccharide and lignin in its cell wall [26]. Every year, more than 15 million tons are produced from palm oil processing in Indonesia [27], most of which are not efficiently utilized. The higher the oil palm production is, the more OPEFB waste is produced. OPEFB waste can reach more than 50% of the total weight of the solid waste. In addition to being inexpensive and widely available, OPEFB contains approximately 34.9% glucose [20], which can be used as carbon source for bacterial metabolism and fungal [28,29].

On the other hand, global leather demand continues to increase every year, reaching a value of 93.2 billion USD in 2016 and is projected to reach 121.16 billion USD in 2022 [30]. This rise in the leather market is believed alternatives pose new challenges, which include their non-biodegradability and the release of various hazardous chemicals which is synonymous with their production processes. The production of animal skins for leather raw materials requires high water, energy and land, resulting in large greenhouse gases (CO2 and NH4) [31]. Animal leather production also requires chemicals such as chromium salts and heavy metal dyes. The use of chromium compounds requires a lot of water, is toxic and carcinogenic to the environment and humans if spilled [31]. Furthermore, the fashion and textile industry is starting to popularize the concept of sustainable fashion as an effort to protect the environment from the dangers of non-biodegradable waste and waste that endangers human life. Sustainable fashion emphasizes the use of environmentally friendly raw materials, minimizing waste, processing production waste, and processing used products [32,33].

The challenge in producing mylea primarily lies in selecting the appropriate media and fermentation agents [2,34,35]. Several studies have explored cost-effective and readily available media options, such as molasses, industrial waste, and fruit waste [36]. Fruit waste like banana, mangosteen, sapodilla, pear, apple, and coconut water are recognized for producing mylea with higher yields [37]. Nevertheless, the mylea produced by this fruit waste does tend to be less durable than premium animal leather or synthetic polyurethane (PU). Being made from organic matter, mycelium leather is vulnerable to degradation in high-humidity conditions and may also pose a flammability risk. Ongoing research in fungal biotechnology, substrate engineering, and post-processing techniques will be critical to enhancing its viability and competitiveness in commercial markets. Furthermore, the economic feasibility of scaling up the production of mycelium-based composites (MBCs) remains uncertain, largely due to the limited amount of research focused on this area [38]. Likewise, there is a noticeable lack of studies examining the long-term performance of MBCs, particularly when used as imitation leather, highlighting the urgent need for further investigation in this field.

Considering the potential of OPEFB waste and white rot fungi as a fermentation starter for mylea production, this study focused on producing mylea using OPEFB waste as a substrate and white rot fungi as an inoculum. Mycelium is treated with boiling, plasticization, drying, pressing, waxing, and adding tencel cloth to become mylea. The study involved morphological evaluation using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), tensile strength tests of the resulting mycelial sheets, and flammability behavior. The characterization results of mylea derived from OPEFB waste can be further investigated regarding its potential utilization for imitation leather.

By integrating fungal biotechnology with waste valorization and material engineering, this study significantly advances the development of regionally relevant, sustainable biomaterials and fills a gap in the current literature concerning the use of oil palm biomass for bioleather production.

In this study, the substrate utilized was oil palm empty fruit bunch (OPEFB) fiber, obtained from the Kertajaya Palm Oil mill located in Banten, Indonesia. The bunches were air-dried for two weeks until they reached a moisture content of 8.0%. Subsequently, they were processed using a screw press and cut into fibers measuring approximately 10 to 15 mm in length (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Crushed and dried OPEFB powder for use in this study

The white rot fungus Ganoderma lucidum used in this study was obtained from the Microbiology Laboratory at the School of Life Sciences and Technology, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Indonesia. The fungal cultures were initially grown on agar plates containing 3% malt extract, 0.3% soy peptone, and 1.5% agar at pH 5.6. Incubation was carried out at 25°C–26°C with 60% relative humidity using 9.4 cm diameter petri dishes. All chemicals utilized in this study were sourced from Bratachem, Jakarta, Indonesia.

A culture of G. lucidum grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) was sectioned into squares measuring 1.0 cm × 1.0 cm. These culture segments were then inoculated into a 400-g substrate composed of a mixture of 313 g of dried cracked corn and 36.36 g of sawdust.

To prepare the substrate, cracked corn was hydrated until its weight reached 363.64 g. Sawdust was subsequently added to achieve a total substrate weight of 400 g. The mixture was transferred into a heat-resistant container and sterilized in an autoclave at 121°C for 15 min to ensure it was free from contaminants prior to inoculation.

Once the substrate had cooled after sterilization, it was inoculated with pieces of the fungal culture and incubated at room temperature (around 25°C) in darkness for 2–3 weeks. During this period, the fungus proliferated, forming a white mycelial layer that completely covered the substrate. After full colonization, the mycelium-covered substrate was ground using a mechanical grinder to produce a uniform particle size of approximately 1–3 mm, which was then used as powdered inoculum for the next stage. The grinding process was carried out under sterile conditions, with all equipment disinfected using 70% ethanol and sterilized under UV light to reduce the risk of contamination.

2.2.2 Production of Mycelium Leather (Mylea)

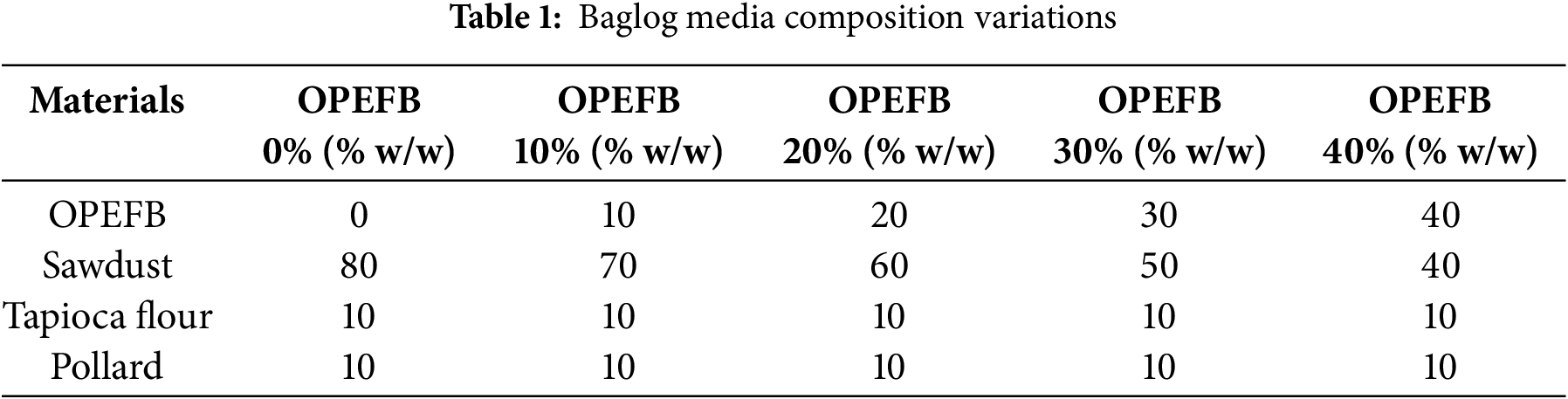

The baglog substrate was formulated by combining materials based on the composition variations outlined in Table 1, incorporating OPEFB at proportions of 0%, 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40% of the total substrate weight. The mix of sawdust, tapioca flour, and pollard offered a well-balanced combination of structure, nutrients, and aeration, creating optimal conditions for vigorous and uniform mycelial development, essential for producing high-quality mycelium-based materials. These composition variations were intended to evaluate the impact of OPEFB content on the quality of the resulting mycelium leather. This procedure was adapted from the method described by Bentangan et al. [39]. After thoroughly mixing all components, distilled water was added at a ratio of 60% (v/w) relative to the substrate weight. The mixture was then homogenized and packed into heat-resistant plastic bags. To ensure sterility prior to inoculation, the baglog substrates were sterilized in an autoclave at 121°C for 15 min, with the process repeated twice.

Following sterilization, the powdered fungal inoculum from Section 2.2.1 was introduced into the baglog substrate under aseptic conditions at a 1:10 ratio of inoculum to substrate. The inoculated baglogs were then incubated in dark conditions at a temperature range of 25°C to 35°C for 2–3 weeks, allowing the mycelium to fully colonize the surface of the substrate.

After complete mycelial colonization, the entire contents of the baglog were aseptically transferred into sterile molds measuring 12 cm × 19 cm. These molds were then incubated in the dark at a temperature range of 22°C to 26°C for a period of 4–6 weeks. Throughout this incubation phase, the surface of the developing mycelial mat was gently pressed with a sterile instrument every four days to ensure even growth and to inhibit the development of fruiting bodies.

Once the mycelial mat had developed on the surface of the substrate, it was gently separated to obtain the raw mycelial layer. This involved peeling the mat away from the substrate and cleaning off any residual substrate particles. The resulting unprocessed mycelial mat was then prepared for subsequent processing into mycelium leather.

2.2.3 Finishing Treatment of Mylea

The harvested mylea undergoes post-harvest treatment to enhance its quality, following a method adapted from Bentangan et al. [39]. First, the mycelium layer is separated from the solid OPEFB substrate. It is then sterilized by boiling at 45°C for 15 min, followed by plasticization using a 15% glycerol solution for 1 h, followed by air drying at ambient temperature for 24 h. The air dried mycelium is dried in an oven at 45°C for 6 h in a stretched position, similar to the method used for drying cow leather, ensuring that the mycelium does not shrink. Next, the plasticized mycelium leather was pressed using a hydraulic press at 6 MPa and 60°C for 5 min. After pressing, the mycelium leather was coated with melted paraffin wax applied by brushing. The sheet was heated at 50°C for 10 min to ensure wax penetration, then allowed to cool and dry. In the final stage, Tencel fabric was applied as a reinforcement layer to improve the mechanical strength of the mycelium leather. This fabric was laminated onto the dried mycelium mat using a plasticizer or adhesive and then pressed at 5 MPa for 5 min to ensure proper bonding and integration. Subsequently, the composite material was further pressed and waxed, resulting in a more flexible and durable mylea. The production process of the mylea specimens is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Flow chart of production process of mycelium-based composites

2.2.4 Characterization of Mylea

Morphological characterization of mycelium with different OPEFB ratios was performed using SEM (EVO MA10, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). The samples were coated with a thin layer of carbon (around 20 nm) before imaging with micrographs taken at 10.0 kV at room temperature. The prepared samples were placed in carbon tubes, and micrographs were recorded at 500× magnification.

The mechanical strength of the mylea was analyzed using the tensile strength to describe the capacity of the material to withstand loads. Testing was conducted using a universal testing machine (ZwickRoell GmbH & Co. KG, Ulm, Germany) with tensile strength sample dimensions of 40 mm in length, 20 mm in width, and 0.3–0.7 mm in thickness and a crosshead speed of 2 mm/min.

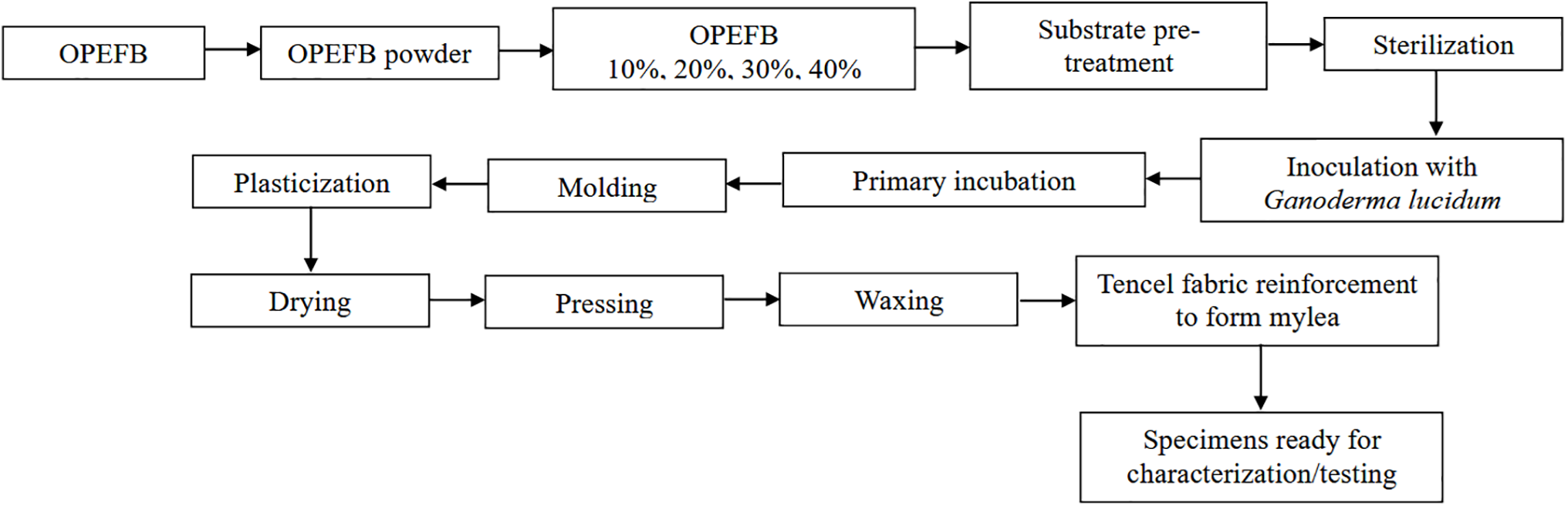

Flame Retardant Behavior Analysis

The investigation of fire behavior using vertical burning test (VBT), mylea were tested using samples with dimensions of 120 mm × 13 mm × 0.78–0.93 mm. Flammability Tester (Wire & Cable Vertical Flame Tester, TF 342, China) used for VBT in accordance with UL 94–2013, as shown in Fig. 3. VBT was determined by using A 40 mm blue methane flame (gas lighter) was then used to ignite the mylea specimen from its short side (flame application time: 10 s).

Figure 3: The scheme for the UL 94 vertical burning test (adapted from Laoutid et al. [40]). Copyright © 2008 Published by Elsevier Ltd.

Flammability testing ratings according to an international standard IEC 60695-11-10, including V-0 (flame extinguishes within 10 s with no dripping), V1 (flame extinguishes within 30 s with no dripping), V2 (flame extinguishes within 10 s with dripping), and no rating.

3.1 Pure Grown Mycelium on Various Composition of OPEFB

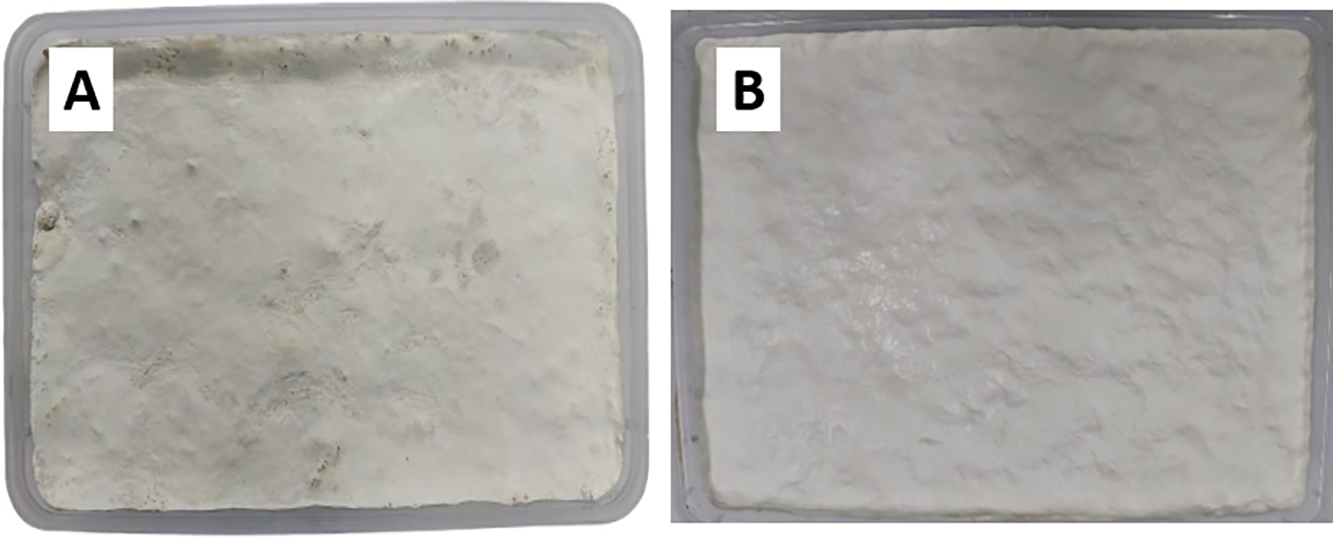

We used four different compositions of OPEFB to investigate the mechanical properties of a hybrid tissue with 10%, 20%, 30% and 40% OPEFB. Based on the results obtained, the variation with a composition of 20% OPEFB showed the best results. This is indicated by the mycelium surface being evenly white, indicating optimal growth and supportive media conditions (Fig. 4). On the other hand, variations with a higher OPEFB composition (30% OPEFB and 40% OPEFB) tend to experience contamination by other fungi. Therefore, this myleae was not used for further testing. This is likely due to the increased availability of lignocellulosic material and high moisture retention, which together create a favorable environment for the growth of competing fungal species. OPEFB is rich in cellulose and hemicellulose, but has a relatively low nitrogen content [41] and porous structure [42], making it more susceptible to colonization by fast-growing molds or opportunistic fungi, especially when not properly sterilized or supplemented with antifungal measures.

Figure 4: The production of mycelium leather with a composition of 10% (A) and 20% (B) OPEFB

The growth of the fungi was very different in various compositions OPEFB used. In the solid-state fermentation (SSF), all fungi grew quickly and reliably without requiring any treatment between inoculation and harvest. The amount of mycelium produced was not quantified, as a representative number would have required dehydration, which was not possible within the scope of this study.

3.2 Characterization of Mycelium Leather

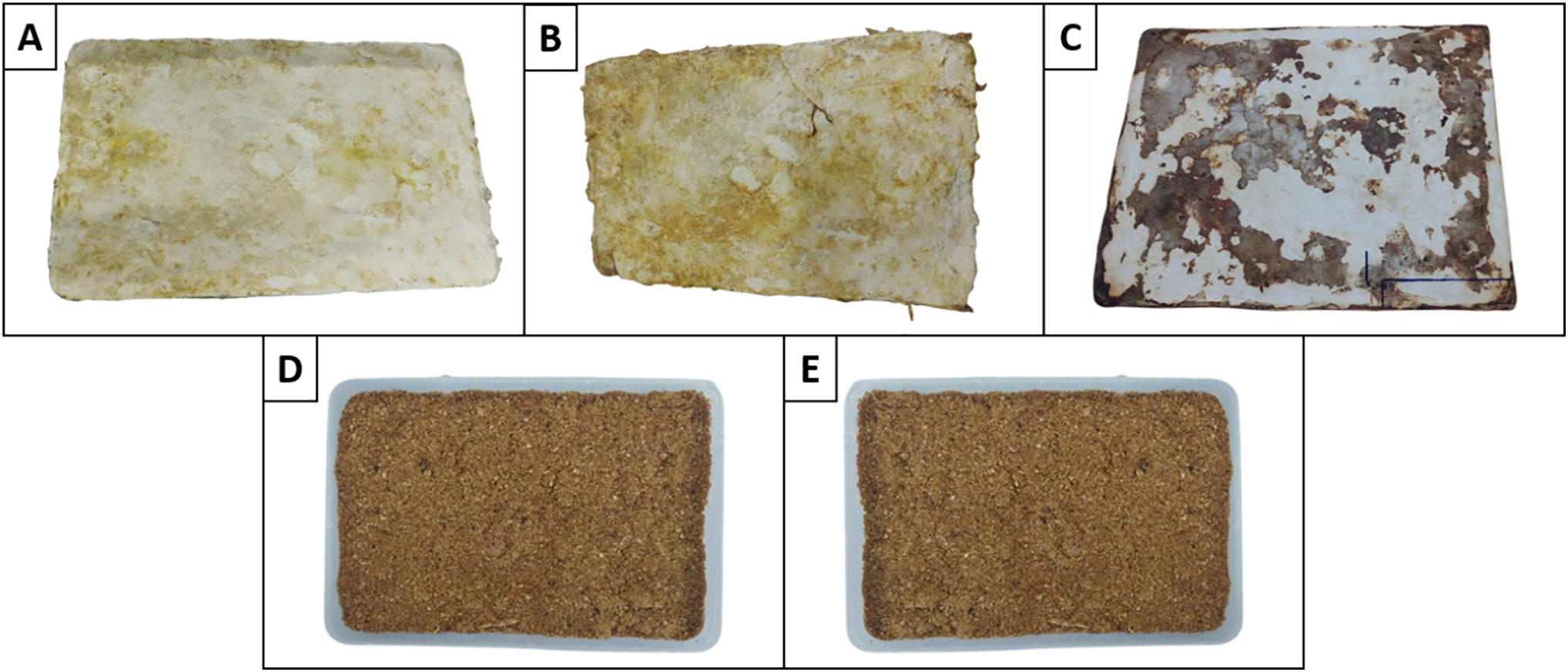

The mycelium are treated with boiling, plasticization, drying, pressing, waxing, and the addition of tencel fabric to produce mylea that are more flexible and strong. The mylea was showed growth on the patches (Fig. 5), the mylea structures with G. lucidum were already hydrophobic after one week, indicating that they were already completely covered with a thin, macroscopically not visible mycelial layer. This is the case with 10% OPEFB was deposits melanin with increasing growth time, which is recognisable by a brownish discolouration [43].

Figure 5: Presented are the mylea on various composition of OPEFB media. (A) 0% OPEFB; (B) 10% OPEFB; (C) 20% OPEFB; (D) 30% OPEFB; and (E) 40% OPEFB

The results indicate that the 20% OPEFB composition produced the best mycelium leather. This variation exhibited a uniform white mycelium surface, suggesting optimal fungal growth and a well-balanced substrate condition. In contrast, higher OPEFB compositions (30% and 40%) were prone to contamination during the baglog phase. Contamination during the fermentation process degraded the quality and fail of the mylea formation. The growth of contaminating fungi is likely due to the increased lignin content in the substrate, which is more difficult to decompose through natural fermentation [44]. As lignin degrades, toxic byproducts may be released, inhibiting the growth of G. lucidum and preventing the formation of a strong and uniform mycelium network. These byproducts may support the growth of competing microorganisms, disrupting the biomaterial formation process. Consequently, using a higher percentage of OPEFB is not ideal for mycelium leather production.

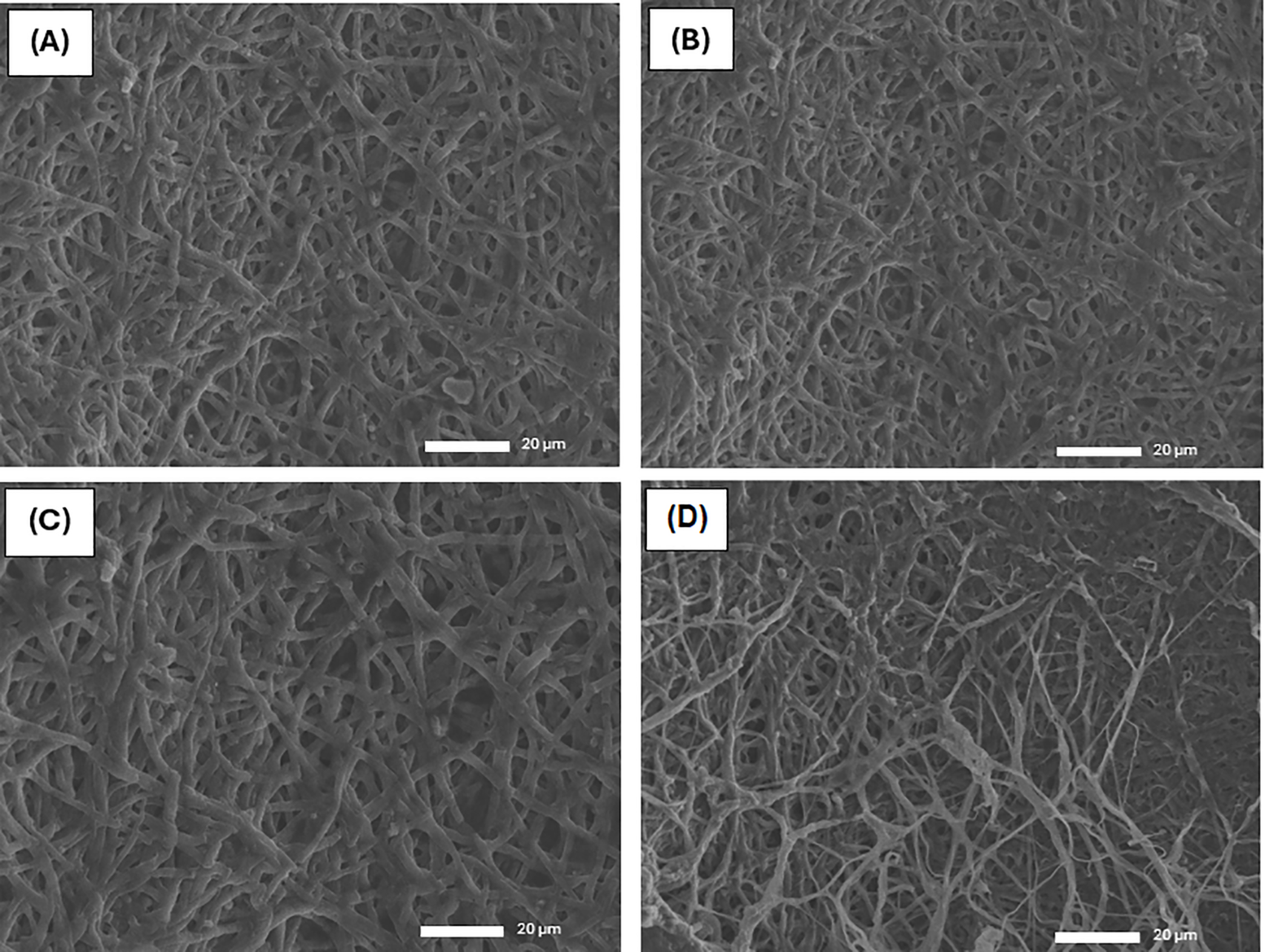

The SEM images of mycelium leather cultivated on substrates with a low OPEFB ratio display a relatively compact and uniform hyphal network (Fig. 6A,B). The hyphae are fine, tightly interwoven, and well-developed, resulting in a dense surface with minimal voids and a continuous, homogeneous structure. This suggests optimal nutrient conditions and minimal disruption from fibers, allowing for effective hyphal extension and branching [45]. In contrast, at higher OPEFB ratios of 30% and 40%, the SEM images (Fig. 6C,D) reveal a more porous and heterogeneous hyphal network. The hyphae appear thicker and less uniform, with noticeable gaps and irregularities. Remnants of OPEFB fibers are partially integrated into the matrix and can be seen on the surface, indicating incomplete colonization. These observations point to a balance between reduced nutrient availability and physical barriers created by the coarser OPEFB particles.

Figure 6: SEM micrograph of (A) 10% OPEFB; (B) 20% OPEFB; (C) 30% OPEFB; and (D) 40% OPEFB

As the OPEFB ratio increases, the continuity and density of the mycelial network decrease, with a visible transition from a tightly bound, homogenous mat at low OPEFB levels to a more open, discontinuous, and fiber-exposed matrix at high OPEFB content. These morphological changes are expected to influence the mechanical properties, flexibility, and water absorption of the resulting mycelium leather [46]. To address this issue, chemical sterilization methods such as NaOH treatment could be explored to break down lignin more effectively, reducing toxic byproducts and creating a more suitable growth environment for G. lucidum. Meanwhile, the 10% and 20% OPEFB samples successfully developed into moldable mycelium leather, confirming that a controlled OPEFB composition is crucial in balancing structural integrity and contamination resistance. This finding highlights the importance of optimizing substrate composition to ensure efficient and high-quality mycelium leather production.

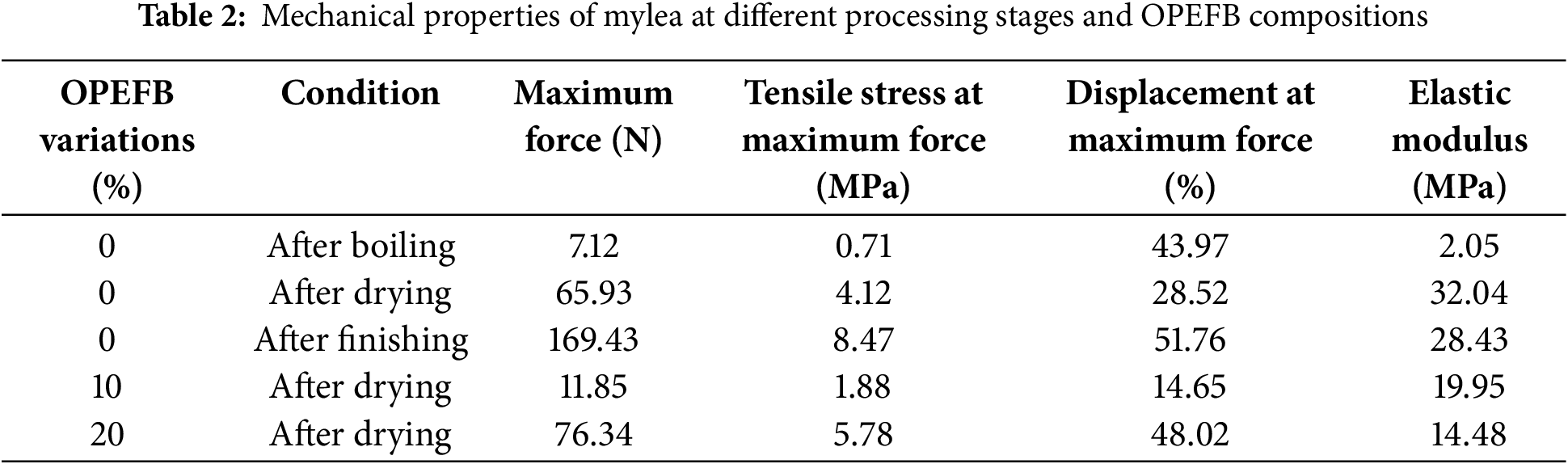

3.2.1 Mechanical Properties Analysis

The mechanical properties of mycelium-based leather (Mylea) are significantly affected by both the processing methods and the proportion of OPEFB in the substrate. Gaining a clear understanding of these influences is essential for enhancing the material’s strength, flexibility, and durability. To explore these impacts, tensile strength tests were performed on Mylea samples processed under different conditions—boiling, drying, and finishing—and incorporating various OPEFB levels (0%, 10%, and 20%). The results, summarized in the following table, highlight how each processing stage and OPEFB concentration contribute to changes in the material’s mechanical behavior.

As shown in Table 2, Mylea undergoes notable changes in tensile strength, strain, and elasticity as it progresses through different stages of processing: boiling, drying, and finishing. Initially, after boiling, the sample with 0% OPEFB exhibited the weakest mechanical properties, with a tensile stress of only 0.71 MPa and a maximum force of 7.12 N. The low elastic modulus of 2.05 MPa further indicates that the material was highly flexible but fragile at this stage, likely due to the high moisture content and underdeveloped structural integrity [47,48].

A significant improvement was observed after drying, where the tensile stress increased to 4.12 MPa and the maximum force reached 65.93 N. This suggests that moisture removal played a crucial role in strengthening the mycelium structure, making it more resistant to applied forces. The elastic modulus also rose sharply to 32.04 MPa, meaning the material became stiffer and more rigid, which is beneficial for applications requiring durability. However, after the finishing process, which involved adding a layer of Tencel fabric, the mechanical properties further improved, with the tensile stress reaching 8.47 MPa and the maximum force increasing dramatically to 169.43 N. While this enhancement suggests improved mechanical performance, it is important to note that the increase in strength was not solely due to the mycelium itself but also the reinforcing effect of the Tencel fabric [49]. Interestingly, the elastic modulus slightly decreased to 28.43 MPa after finishing, indicating that while the material became stronger, it also retained a degree of flexibility, likely due to the properties of the fabric layer.

Beyond the effect of processing, variations in OPEFB composition also played a critical role in determining Mylea’s mechanical properties. When comparing dried samples, the 0% OPEFB variation had a tensile stress of 4.12 MPa and an elastic modulus of 32.04 MPa, suggesting a relatively strong yet rigid structure. However, with the addition of 10% OPEFB, the tensile stress dropped to 1.88 MPa, and the elastic modulus decreased to 19.95 MPa, making the material weaker and more flexible. This indicates that a small amount of OPEFB may not provide enough structural support for robust mycelium development [50]. In contrast, the sample with 20% OPEFB showed a notable improvement in mechanical strength, with a tensile stress of 5.78 MPa—higher than both the 0% and 10% OPEFB samples. However, despite this increase in tensile strength, the elastic modulus decreased further to 14.48 MPa, indicating that while the material became stronger, it also became more flexible. This suggests that OPEFB contributes to a balance between strength and elasticity, where an optimal amount, such as 20%, enhances mechanical performance without making the material too rigid or brittle.

Overall, these results highlight the significant impact of processing stages and OPEFB composition on Mylea’s mechanical properties. The finishing stage with Tencel fabric led to the highest tensile strength, though this was mainly due to external reinforcement. Among dried samples, 20% OPEFB provided the best balance of strength and flexibility, while 10% OPEFB resulted in the weakest properties, suggesting insufficient structural support. Optimizing substrate composition and processing techniques is crucial for enhancing mycelium-based materials. Additionally, studies indicate that Mylea’s tensile properties depend on mushroom mycelia, particularly in forming the mycelium binder network and colonizing the substrate. The growth substrate also significantly influences mechanical performance, aligning with previous research showing that both substrate type and mycelium structure affect tensile strength [20,51]. On the other hand, the mechanical properties of mycelium-based composites (MBCs) are significantly also impacted by the loading level of the substrate—in this case, the percentage of OPEFB [20]. The loadings 20% tend to provide a good balance between fungal growth and structural integrity, this ratio OPEFB is likely the best balance for fabricating structurally sound and biodegradable bio-composites like Mylea.

Several previous studies [20,52] have suggested that the high tensile strength of MBCs in this study were compared with the results of research by Apples et al. [20] who used T. multicolor or P. ostreatus when grown on rapeseed straw. Additionally, Aiduang et al. [52] found that MBC of Ganoderma williamsianum exhibited also lower tensile strength (0.43 MPa) when grown on sawdust of rubber tree. The obtained tensile strength values of MBCs in this study had a higher tensile strength than with polystyrene foam (0.15–0.7 MPa) [53], phenolic formaldehyde resin foam (0.19–0.46 MPa) [54], and polyimide foam (0.44–0.96 MPa) [55].

The mylea had different mechanical properties in tensile strength, and elastic modulus with natural leathers. Mylea exhibited the tensile, and elastic modulus properties similar to natural leather due to the base tencel fabric and plasticization treatment of mylea. The tensile strength properties of mylea using tencel as a base fabric were similar to those of natural leather, although its were lower than natural leather. Its compressive elasticity was excellent and lighter than that of natural leather although it was the heaviest among artificial leathers.

3.2.2 Fire Properties Analysis

Mylea, made from fungal biomass and plant-based substrates, can be naturally flammable. Conducting flammability tests is essential to assess its safety and functional performance in real-world uses, particularly in sectors like fashion, interior design, automotive, and consumer products. These tests allow for a direct comparison of fire risk between mycelium leather and conventional materials such as PVC, PU leather, and animal leather.

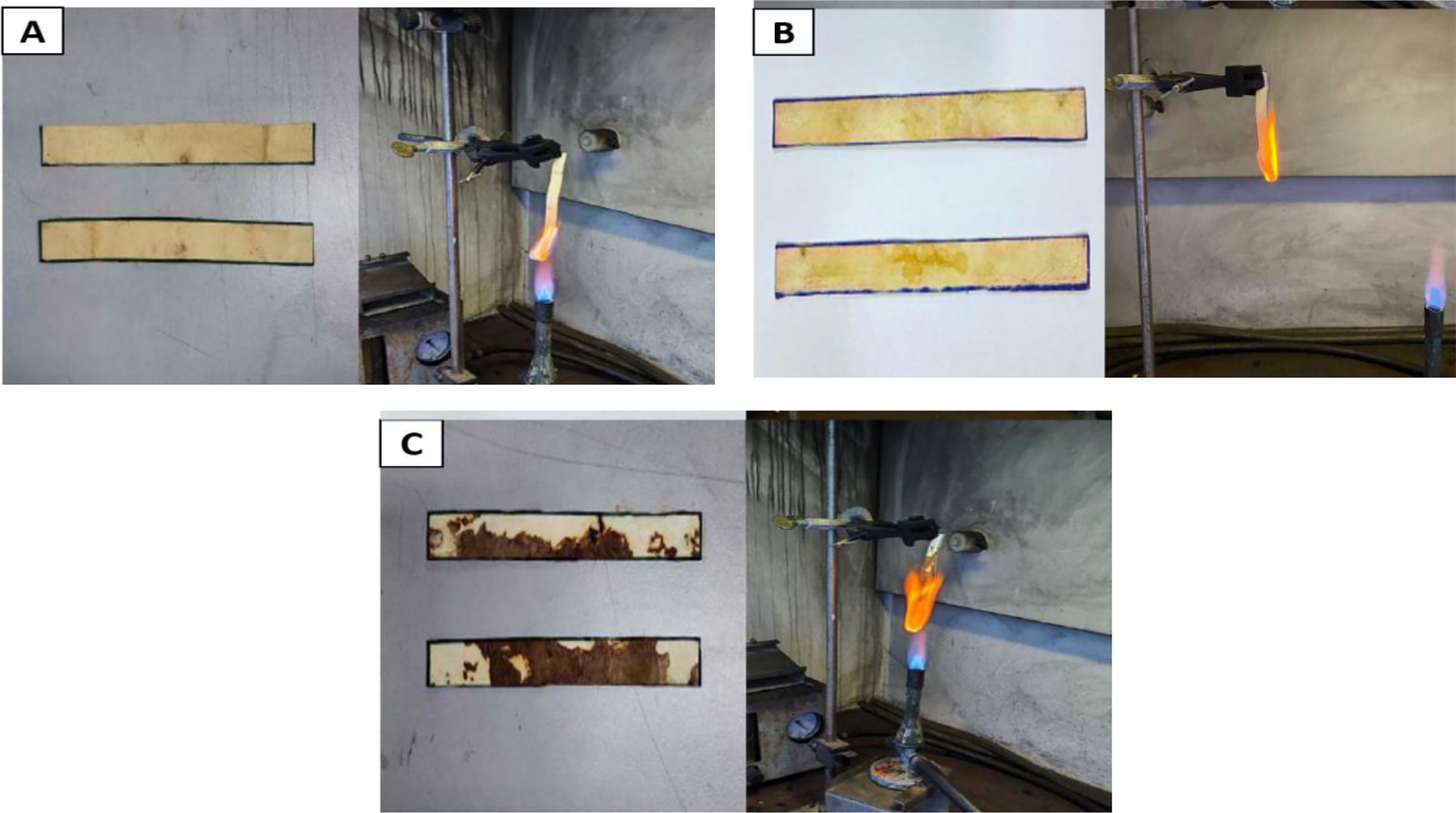

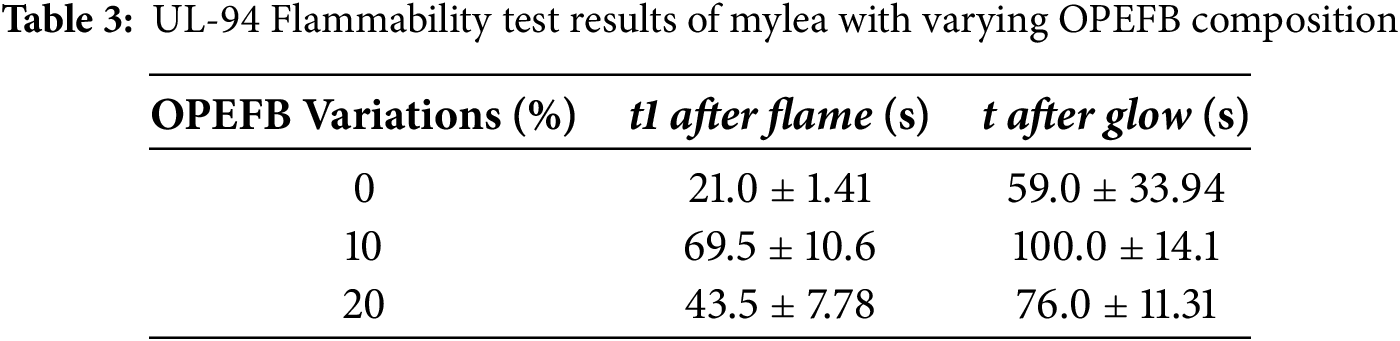

The UL-94 vertical burning test was used to evaluate the fire resistance of Mylea, simulating the material’s behavior after 10 s of initial flame exposure. The results show that Mylea samples with varying OPEFB compositions in the baglog substrate displayed different burning characteristics (Fig. 7, Table 3).

Figure 7: Vertical flammability test (UL-94) results of Mylea samples containing 0% OPEFB (A), 10% OPEFB (B), and 20% OPEFB (C)

All samples failed to meet the UL-94 classification standards (V-0, V-1, or V-2), which indicates that none of them are sufficiently fire-retardant for safety applications [56]. Smoldering combustion with visible smoke was observed in all variations, confirming the presence of sustained post-flame reactions. As noted by Torero [57], chemical reactions in smoldering are closely tied to mass transfer and heat conduction.

Among the samples, Mylea without OPEFB (0%) showed the shortest after flame time (21.0 ± 1.41 s), followed by the 20% OPEFB sample (43.5 ± 7.78 s). Interestingly, the 10% OPEFB sample had the longest burning duration (69.5 ± 10.6 s), indicating the poorest fire resistance. A similar trend was observed in the after glow parameter, where the 10% OPEFB sample again showed the longest smoldering time (100.0 ± 14.1 s), suggesting prolonged heat retention in the material structure. The results from the vertical flammability test indicate that the tested leather can be categorized as an ignitable material, with an average flame duration of 21.0 ± 1.41 s. In contrast, artificial PU leather ignites readily and exhibits a flame spread rate of 66 mm/min [58]. For surface flame exposure, natural leather burns after 18 s [58], whereas mycelium leather (mylea) ignites much faster, within just 3 s. When the flame is applied to the edge, natural leather takes about 5 s to ignite [58], while artificial leather catches fire immediately upon contact. It then burns slowly and continues to glow until completely turned to ash. Once ignited, natural leather tends to smoulder at a slow pace, glows persistently, and undergoes shrinkage.

The lack of improvement in flame resistance despite OPEFB addition suggests that the fiber-rich nature of OPEFB, while beneficial for structural reinforcement, may introduce more flammable organic components into the composite. Surprisingly, although the 20% OPEFB sample contains more lignocellulosic material than the 10% sample, it performed better in the flammability test. The quantitative relationship between moisture content and flame retardancy is complex and depends on the material and type of flame retardancy mechanism. The material’s microstructure and chemical composition have a major influence on flame retardancy, determining how easily the material ignites, sustains combustion, and forms protective char. The resulting mylea structure revealed that samples with higher moisture exhibited swollen hyphal networks and reduced pore diameter, which slowed combustion front propagation. However, microstructural compaction, pore morphology, and chemical composition (especially chitin, protein, and nitrogen content) can significantly modulate this relationship [59]. Thus, while increasing moisture content is a straightforward method to enhance flame resistance, optimizing microstructure and biopolymer content provides a more robust, permanent improvement.

One plausible explanation for this outcome relates to moisture retention and material drying post-harvest. During the drying process, the Mylea sample with 10% OPEFB consistently showed a drier and lighter structure compared to the 20% sample. This lower moisture content may have made the 10% sample more susceptible to ignition and longer sustained combustion, as moisture plays a crucial role in delaying pyrolysis and flame propagation. In contrast, the slightly higher retained moisture in the 20% sample could have suppressed the rate of combustion and limited thermal degradation, despite its higher OPEFB content.

Meanwhile, the chemical composition of the growth matrix for mycelium plays a dual role: it affects not only the biological performance of the fungal growth but also the chemical and physical properties of the final composite, including flammability [60]. Changes in the matrix composition can lead to significant shifts in mycelium metabolism, biomass composition, and char yield, all of which influence flame resistance. Thus, matrix modification becomes a powerful treatment not only for optimizing growth but also for enhancing the fire safety performance of mycelium-based materials such as mylea.

Therefore, while the incorporation of OPEFB influences the material’s structural characteristics, it does not directly enhance fire resistance and may even worsen it when moisture balance is not controlled. Overall, the fire performance of all Mylea samples remains inferior to previous studies on mycelium composites, such as those reported by Chulikavit et al. [61], suggesting the need for further optimization in formulation or post-processing. Based on the test results, the time for fire extinguishing was further reduced by addition OPEFB in media. The mylea samples exhibited higher flammability with shorter times required for the fire to be extinguished. It is plausible that the fire resistance of the material improves through conversion into mycelium-based materials, albeit the outcomes are still inferior to those of previous research by Chulikavit et al. [61].

This study found that Ganoderma lucidum is most effective for mycelium leather production when grown on solid OPEFB media, with a 20% OPEFB composition yielding the best results within 6–8 weeks. Tensile testing revealed that mycelium leather with 0% OPEFB, after finishing, had a tensile strength of 8.47 MPa, but this value was influenced by the addition of Tencel fabric. Without the fabric layer, the tensile strength would be only 4.12 MPa. On the other hand, mycelium leather with 20% OPEFB showed a tensile strength of 5.78 MPa and a lower elastic modulus of 14.48 MPa, indicating greater flexibility and reduced stiffness. Flammability tests indicated that the mycelium leather with 20% OPEFB had a longer burn time (43.5 ± 7.78 s) compared to the 0% OPEFB sample (21.0 ± 1.41 s) and 10% OPEFB sample (69.5 ± 10.6 s), though neither variation met the fire resistance standards of UL 94 V-0, V-1, or V-2. Overall, the incorporation of 20% OPEFB improved both the flexibility and tensile strength of mycelium leather compared to 0% OPEFB, although fire resistance remained unchanged.

Mylea, produced from OPEFB and G. lucidum, and enhanced through processes such as plasticization, Tencel fabric reinforcement, pressing, and waxing, demonstrates excellent durability, flexibility under mechanical stress, and improved fire resistance. Importantly, this mycelium-based leather is developed without the use of harmful synthetic binders or coatings, preserving its environmental advantages over both traditional and synthetic leathers.

Mass production continues to pose a significant challenge that must be tackled and optimized moving forward. Further study is needed to optimize the mechanical properties and improve fire resistance as well as biodegradable characteristics of mylea for industrial applications.

Acknowledgement: The authors are grateful for the Palm Oil Plantation Fund Management Agency (BPDPKS), Indonesia. The authors also would like to thank the scientific and technical support provided by the Laboratory of Microbiology, School of Life Sciences and Technology, Institut Teknologi Bandung (ITB), Indonesia.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by the Palm Oil Plantation Fund Management Agency (BPDPKS), Indonesia 2024.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Pingkan Aditiawati and Kamarisima; methodology, Pingkan Aditiawati and Rudi Dungani; software, Neil Priharto, Muhammad Iqbal Ar-Razy Suwardi and Muhammad Rizki Ramdhani; validation, Maya Fitriyanti and Dzulianur Mutsla; formal analysis, Tirto Prakoso; investigation, Widya Fatriasari; resources, Rudi Dungani; data curation, Kamarisima; writing—original draft preparation, Pingkan Aditiawati, Kamarisima and Rudi Dungni; writing—review and editing, Maya Fitriyanti and Dzulianur Mutsla; visualization, Kamarisima; supervision, Pingkan Aditiawati; project administration, Pingkan Aditiawati; funding acquisition, Pingkan Aditiawati. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data will be made available on request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Alemu D, Tafesse M, Mondal AK. Mycelium-based composite: the future sustainable biomaterial. Int J Biomater. 2022;2022(1):401528. doi:10.1155/2022/8401528. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Elsacker E, Vandelook S, Peeters E. Recent technological innovations in mycelium materials as leather substitutes: a patent review. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023;11:1204861. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2023.1204861. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Yang L, Park D, Qin Z. Material function of mycelium-based bio-composite: a review. Front Mater. 2021;8:737377. doi:10.3389/fmats.2021.737377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. de Ulzurrun VD, Baetens JM, van den Bulcle J, De Baets B. Modelling three-dimensional fungal growth in response to environmental stimuli. J Theor Biol. 2017;414(8):35–49. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2016.11.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Jones M, Weiland K, Kujundzic M, Theiner J, Kählig H, Kontturi E, et al. Waste-derived low-cost mycelium nanopapers with tunable mechanical and surface properties. Biomacromolecules. 2019;20(9):3513–23. doi:10.1021/acs.biomac.9b00791. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Wang Z, Wang H, Kang Z, Wu Y, Xing Y, Yang Y. Antioxidant and anti-tumour activity of triterpenoid compounds isolated from Morchella mycelium. Arch Microbiol. 2020;202(7):1677–85. doi:10.1007/s00203-020-01876-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Abhijith R, Ashok RA, Rejeesh CR. Sustainable packaging applications from mycelium to substitute polystyrene: a review. Mater Today Proc. 2018;5(1):2139–45. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2017.09.211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Köhnlein MBM, Abitbol T, Oliveira AO, Magnusson MS, Adolfsson KH, Svensson SE, et al. Bioconversion of food waste to biocompatible wet-laid fungal films. Mater Des. 2022;216(3):110534. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2022.110534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Jiang L, Walczyk D, Mcintyre G. A new process for manufacturing biocomposite laminate and sandwich parts using mycelium as a binder. In: Jiang L, editor. Proceedings of American Society for Composites 29th Technical Conference; 2013; San Diego, CA, USA. p. 141–55. doi:10.1115/msec2016-8864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Mohorčič M, Friedrich J, Renimel I, André P, Mandin D, Chaumont JP. Production of melanin bleaching enzyme of fungal origin and its application in cosmetics. Biotechnol Bioprocess Eng. 2007;12(3):200–6. doi:10.1007/BF02931093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Islam MR, Tudryn G, Bucinell R, Schadler L, Picu RC. Stochastic continuum model for mycelium-based bio-foam. Mater Des. 2018;160(1):549–56. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2018.09.046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Jones M, Mautner A, Luenco S, Bismarck A, John S. Engineered mycelium composite construction materials from fungal biorefineries: a critical review. Mater Des. 2020;187(1):108397. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2019.108397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Walter N, Gürsoy B. A study on the sound absorption properties of mycelium-based composites cultivated on waste paper-based substrate. Biomimetics. 2022;7(3):100. doi:10.3390/biomimetics7030100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Gezer ED, Kuştaş S. Acoustic and thermal properties of mycelium-based insulation materials produced from desilicated wheat straw—part B. BioResour. 2024;19(1):1348–64. doi:10.15376/biores.19.1.1348-1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Amobonye A, Lalung J, Awasthi MK, Pillai S. Fungal mycelium as leather alternative: a sustainable biogenic material for the fashion industry. Sustain Mater Technol. 2023;38(164):e00724. doi:10.1016/j.susmat.2023.e00724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Bustillos J, Loganathan A, Agrawal R, Gonzalez BA, Perez MG, Ramaswamy S, et al. Uncovering the mechanical, thermal, and chemical characteristics of biodegradable mushroom leather with intrinsic antifungal and antibacterial properties. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2020;3(5):3145–315. doi:10.1021/acsabm.0c00164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Sydor M, Bonenberg A, Doczekalska B, Cofta G. Mycelium-based composites in art, architecture, and interior design: a review. Polymers. 2022;14(1):145. doi:10.3390/polym14010145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Hoenerloh A, Ozkan D, Jordan DS. Multi-organism composites: combined growth potential of mycelium and bacterial cellulose. Biomimetics. 2022;7(2):5. doi:10.3390/biomimetics7020055. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Haneef M, Ceseracciu L, Canale C, Bayer IS, Heredia-Guerrero JA, Athanassiou A. Advanced materials from fungal mycelium: fabrication and tuning of physical properties. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):41292. doi:10.1038/srep41292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Appels FVW, Camere S, Montalti M, Karana E, Jansen KMB, Dijksterhuis J, et al. Fabrication factors influencing mechanical, moisture and water-related properties of mycelium-based composites. Mater Des. 2019;161:64–71. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2018.11.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang M, Zhang Z, Zhang R, Peng Y, Wang M, Cao J. Lightweight, thermal insulation, hydrophobic mycelium composites with hierarchical porous structure: design, manufacture and applications. Compos B Eng. 2023;266:111003. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2023.111003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kachrimanidou V, Papadaki A, Papapostolou H, Alexandri M, Gonou-Zagou Z, Kopsahelis N. Ganoderma lucidum mycelia mass and bioactive compounds production through grape pomace and cheese whey valorization. Molecules. 2023;28(17):6331. doi:10.3390/molecules28176331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Saini R, Kaur G, Brar GK. Textile residue-based mycelium biocomposites from Pleurotus ostreatus. Mycology. 2023;15(4):683–9. doi:10.1080/21501203.2023.2278308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ghazvinian A, Gürsoy B. Mycelium-based composite graded materials: assessing the effects of time and substrate mixture on mechanical properties. Biomimetics. 2022;7(2):48. doi:10.3390/biomimetics7020048. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Schoder KA, Krumpel J, Muller J, Lemmer A. Effects of environmental and nutritional conditions on mycelium growth of three basidiomycota. Mycol. 2024;52(2):124–34. doi:10.1080/12298093.2024.2341492. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Elgharbawy AA, Alam MZ, Moniruzzaman M, Kabbashi NA, Jamal P. Chemical and structural changes of pretreated empty fruit bunch (EFB) in ionic liquid-cellulase compatible system for fermentability to bioethanol. 3 Biotech. 2018;8(5):236. doi:10.1007/s13205-018-1253-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Nabila R, Hidayat W, Haryanto A, Hasanudin U, Iryani DA, Lee S, et al. Oil palm biomass in Indonesia: thermochemical upgrading and its utilization. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2023;176:113193. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2023.113193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Abebaw G, Abate B. Chrome tanned leather waste dechroming optimization for potential poultry feed additive source: a waste to resources approach of feed for future. J Environ Pollut Manag. 2018;1(1):1–6. [Google Scholar]

29. Ying TY, Teong LK, Abdullah WNW, Peng LC. The effect of various pretreatment methods on oil palm empty fruit bunch (EFB) and kenaf core fibers for sugar production. Procedia Environ Sci. 2014;20:328–35. doi:10.1016/j.proenv.2014.03.041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Fouda-Mbanga BG, Tywabi-Ngeva Z. Application of pineapple waste to the removal of toxic contaminants: a review. Toxics. 2022;10(10):561. doi:10.3390/toxics10100561. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Ibrahim W, Mutia R, Nurhayati N. Penggunaan Kulit Nanas Fermentasi dalam Ransum yang Mengandung Gulma Berkhasiat Obat terhadap Organ Pencernaan Ayam BroilerJ. Sain Peternak. 2018;13(2):214–22. (In Indonesian). doi:10.31186/jspi.id.13.2.214-222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Tinni SH, Islam MH, Fatima K, Ali MA. Impact of tanneries waste Disposal on environment in some selected areas of Dhaka City Corporation. J Environ Sci Natur Res. 2015;7(1):149–56. doi:10.3329/jesnr.v7i1.22164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Kulsum U. Sustainable fashion as the early awakening of the clothing industry post corona pandemic. Inter J Soc Sci Busi. 2020;4(3):422–9. doi:10.23887/ijssb.v4i3.26438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Kniep J, Graupner N, Reimer JJ, Müssig J. Mycelium-based biomimetic composite structures as a sustainable leather alternative. Mater Today Commun. 2024;39(1):109100. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2024.109100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Rathinamoorthy R, Sharmila Bharathi T, Snehaa M, Swetha C. Mycelium as sustainable textile material-review on recent research and future prospective. Int J Cloth Sci Technol. 2023;35(3):454–76. doi:10.1108/IJCST-01-2022-0003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Yang. F, Zhang Z, Yuan J, Xu J, Ji Q, Bai Y. Eco-friendly production of leather-like material from bacterial cellulose and waste resources. J Clean Prod. 2024;476(1):143700. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.143700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Kanagaraj J, Senthilvelan T, Panda RC, Kavitha S. Eco-friendly waste management strategies for greener environment towards sustainable development in leather industry: a comprehensive review. J Clear Prod. 2015;89(3):1–17. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.11.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Camilleri E, Narayan S, Lingam D, Blundell R. Mycelium-based composites: an updated comprehensive overview. Biotechnol Adv. 2025;79(1):108517. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2025.108517. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Bentangan MA, Nugroho AR, Hartantyo R, Ilman RZ, Ajidarma E, Nurhadi MY. Mycelium material, its method to produce and usage as leather substitute [Internet]. 2018 Dec 26 [cited 2025 May 1]. Available from: https://patents.google.com/patent/WO2020136448A1/en?oq=WO2020136448A1. [Google Scholar]

40. Laoutid F, Bonnaud L, Alexandre M, Lopez-Cuesta JM, Dubois P. New prospects in flame retardant polymer materials: from fundamentals to nanocomposites. Mater Sci Eng R Rep. 2009;63(3):100–25. doi:10.1016/j.mser.2008.09.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Bhardwaj N, Kumar B, Agrawal K, Verma P. Current perspective on production and applications of microbial cellulases: a review. Bioresour Bioprocess. 2021;8(1):95. doi:10.1186/s40643-021-00447-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Rao PR, Ramakrishna G. Oil palm empty fruit bunch fiber: surface morphology, treatment, and suitability as reinforcement in cement composites—a state of the art review. Clean Mat. 2022;6(3):100144. doi:10.1016/j.clema.2022.100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Kalitukha L, Sari M. Fascinating vital mushrooms. Tinder fungus (Fomes fomentarius (L.) Fr.) as a dietary supplement. Int J Res Stud Sci Eng Technol. 2019;6:1–9. [Google Scholar]

44. Hsin KT, Lee HY, Huang YC, Lin GJ, Lin PY, Jimmy YC, et al. Lignocellulose degradation in bacteria and fungi: cellulosomes and industrial relevance. Front Microbiol. 2025;16:1583746. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2025.1583746. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Dullaha S, Hazarikaa DJ, Parveena A, Kakotia M, Borgohaina T, Gautoma T, et al. Fungal interactions induce changes in hyphal morphology and enzyme production. Mycology. 2021;12(4):279–95. doi:10.1080/21501203.2021.1932627. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Leyu G, Li S, Yin J, Li T, Liu X. Morphological and physico-mechanical properties of mycelium biocomposites with natural reinforcement particles. Constr Build Mater. 2021;304(7):124656. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.124656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Rebelo AR, Archer AJ, Chen X, Liu C, Yang G, Liu Y. Dehydration of bacterial cellulose and the water content effects on its viscoelastic and electrochemical properties. Sci Technol Adv Mater. 2018;19(1):203–11. doi:10.1080/14686996.2018.1430981. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Lingam D, Narayan S, Mamun K, Charan D. Engineered mycelium-based composite materials: comprehensive study of various properties and applications. Constr Build Mater. 2023;391(1):131841. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.131841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Zhang Y, Lin JH, Cheng DH, Li X, Wang HY, Lu YH, et al. A Study on tencel/LMPET-TPU/triclosan laminated membranes: excellent water resistance and antimicrobial ability. Membranes. 2023;13(8):703. doi:10.3390/membranes13080703. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Elsacker E, Vandelook S, Damsin B, Wylick AV, Peeters E, Laet LD. Mechanical characteristics of bacterial cellulose-reinforced mycelium composite materials. Fungal Biol Biotechnol. 2021;8(1):18. doi:10.1186/s40694-021-00125-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Abdelhady O, Spyridonos E, Dahy H. Bio-modules: mycelium-based composites forming a modular interlocking system through a computational design towards sustainable architecture. Designs. 2023;7(1):20. doi:10.3390/designs7010020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Aiduang W, Kumla J, Srinuanpan S, Thamjaree W, Lumyong S, Suwannarach N. Mechanical, physical, and chemical properties of mycelium-based composites produced from various lignocellulosic residues and fungal species. J Fungi. 2022;8(11):1125. doi:10.3390/jof8111125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Zouzias D, De Bruyne G, Miralbes R, Ivens J. Characterization of the tensile Behavior of expanded polystyrene foam as a function of density and strain rate. Adv Eng Mater. 2020;22(12):2000794. doi:10.1002/adem.202000794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Wei J, Wei C, Su L, Fu J, Lv J. Synergistic reinforcement of phenol-formaldehyde resin composites by poly (hexanedithiol)/graphene oxide. J Mater Sci Chem Eng. 2015;3:56. doi:10.4236/msce.2015.38009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Shi Y, Hu A, Wang Z, Li K, Yang S. Closed-cell rigid polyimide foams for high-temperature applications: the effect of structure on combined properties. Polymers. 2021;13(24):4434. doi:10.3390/polym13244434. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Page J, Whaley P, Bellingham M, Birnbaum LS, Cavoski A, Dilke DF, et al. A new consensus on reconciling fire safety with environmental & health impacts of chemical flame retardants. Environ Int. 2023;173(11):107782. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2023.107782. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Torero JL, Gerhard JI, Martins MF, Zanoni MAB, Rashwan TL, Brown JK. Processes defining smouldering combustion: integrated review and synthesis. Prog Energ Combust. 2020;81(II):100869. doi:10.1016/j.pecs.2020.100869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Półka M. Leather thermal and environmental parameters in fire conditions. Sustainability. 2019;11(22):6452. doi:10.3390/su11226452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Chulikavit N, Huynh T, Dekiwadia C, Khatibi A, Mouritz A, Kandare E. Influence of growth rates, microstructural properties and biochemical composition on the thermal stability of mycelia fungi. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):15105. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-19458-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Irbe I, Loris GD, Filipova I, Andze L, Skute M. Characterization of self-growing biomaterials made of fungal mycelium and various lignocellulose-containing ingredients. Materials. 2022;15(21):7608. doi:10.3390/ma15217608. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Chulikavit N, Wang C, Huynh T, Yuen ACY, Khatibi A, Kandare E. Fireproofing flammable composites using mycelium: investigating the effect of deacetylation on the thermal stability and fire reaction properties of mycelium. Polym Degrad Stab. 2023;215(11):110419. doi:10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2023.110419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools