Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Identification and Expression Analysis of AP2/ERF Gene Family Members in Different Growth Periods of Magnolia officinalis

1 Key Laboratory of Quality Control and Evaluation of Tradition Chinese Medicine in Mianyang, Mianyang Normal University, Mianyang, 621000, China

2 College of Life Science and Engineering, Southwest University of Science and Technology, Mianyang, 621000, China

3 Mianyang Institute for Food and Drug Control, Mianyang, 621000, China

4 Beichuan Shennong Agriculture Technology Development Co., Ltd., Mianyang, 621000, China

* Corresponding Authors: Qian Wang. Email: ; Hui Tian. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work as the first author

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Recent Research Trends in Genetics, Genomics, and Physiology of Crop Plants–Volume II)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(10), 3061-3084. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.070560

Received 18 July 2025; Accepted 02 September 2025; Issue published 29 October 2025

Abstract

Magnolia officinalis is a perennial deciduous tree that has medicinal properties. The AP2/ERF gene family has a number of roles in long-term growth and metabolism. The expression of this function varies with the growth period. In this work, based on the transcriptome data of Magnolia officinalis, the complete coding gene of Magnolia officinalis was obtained, and the corresponding protein sequence was retrieved from NCBI and compared with the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. After screening, 75 protein sequences from the AP2/ERF gene family were identified and called MoAP2/ERF1–MoAP2/ERF75, followed by bioinformatics analysis. 75 AP2/ERF gene families were found and classified into four subfamilies. Their protein architectures had one or more conserved AP2 domains, which were typically unstable and hydrophilic. Subcellular research revealed that it was primarily located in the nucleus. Among them, the DREB subfamily showed stronger activity in the early growth period of Magnolia officinalis, suggesting that Magnolia officinalis had stronger resistance to adversity during this period. The 15 members of the MoAP2/ERF gene family showed significant differences during different growth periods, and they regulated the gene expression of Magnolia officinalis by binding to DNA. The 15 MoAP2/ERF gene families have a wide range of physiological activities in biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions. Including MoAP2/ERF55 can catalyze imidazole glycerol phosphate synthase activity; MoAP2/ERF39 acts as a transcriptional activator of Pti6.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileMagnolia officinalis Rehd. et Wils. and its variant Magnolia officinalis Rehd. et Wils. var. biloba Rehd. et Wils. are widely distributed in southern China. The dried bark (including root bark and branch bark) of Magnolia officinalis Rehd. et Wils. is used medicinally. According to the Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China (Volume I, 2020 Edition), Magnoliae officinalis Cortex is traditionally employed to treat ailments such as damp stagnation, phlegm, and cough [1]. Among them, lignans (magnolol and honokiol), the main active ingredients of Magnoliae officinalis Cortex, are many potential drug precursors, with pharmacological effects such as anti-tumor [2], nerve protection [3], antibacterial [4], anti-inflammatory [5], anti-oxidation [6], liver function protection [7], and cardiovascular disease treatment [8]. Magnolia officinalis is a deciduous tree with a prolonged growth cycle. Magnolia officinalis must be grown for at least ten years before it may be used medicinally. This shortage of supply has led to the seriousdeforestation of Magnolia officinalis, resulting in the scarcity of wild resources of Magnolia officinalis, and the quality of artificially planted Magnolia officinalis is different. In view of this problem, perhaps the AP2/ERF gene family, one of the largest transcription factor families unique to plants, can provide effective help.

AP2/ERF gene family members contain 1–2 conserved AP2 domains composed of about 60 amino acids [9]. This family regulates downstream gene expression by recognizing specific DNA cis-elements (such as GCC-box and DRE/CRT) and plays a central role in the plant life cycle [10]. For example, the AP2/ERF gene family regulates the development of flowers and fruits [11,12]; responds to pathogens, salt, drought, and low-temperature stress [13–15]; and promotes the accumulation of secondary metabolites [16–18]. According to the number of domains and sequence characteristics, the AP2/ERF gene family is divided into five categories [13]. The AP2 subfamily, which contains two AP2 domains, dominates the regulation of plant development. For example, maize AP2 genes ids1 and sid1 regulate inflorescence meristem [19]; the DREB and ERF subfamilies containing only one AP2 domain play a role in biotic or abiotic stresses and secondary metabolism. For example, the interaction between GmDREB1 and GmERFs can increase the drought tolerance of soybean [20]; SmERF73 regulates the synthesis of tanshinone and salt tolerance [21,22]; the RAV subfamily represented by AP2 and B3 domains is also associated with cold stress, such as the gene CaRAV1 of pepper (Capsicum annuum) [23]; and the Soloist subfamily, whose function is not clear [13]. The AP2/ERF gene family not only has a large branch and a large number of branches but also has a wide and complex function of subordinate regulation. The number of AP2/ERF genes among species is also diverse. They include Hybrid Tea Rose: Rosa × hybrida, 127 AP2/ERF genes [24], Coptis chinensis Franch., 96 AP2/ERF genes [25], Fragaria vesca L., 86 AP2/ERF genes [26], etc. This functional complexity and interspecific differences make the identification and functional exploration of the AP2/ERF gene family necessary.

Up to now, genome-wide identification of AP2/ERF gene families has been completed in many plants, even covering medicinal plants such as Pyrus pyrifolia [27], Yellow Horn [28], Erianthus fulvus [29], and Juglans mandshurica [30]. As a secondary protection plant of Magnolia officinalis in China, except for some mevalonate pathway (MVA)-related genes or Dirigent gene families that have been identified by bioinformatics analysis [31,32], the AP2/ERF gene family that affects growth and metabolism has not been identified. In this study, the AP2/ERF gene family was identified based on Magnolia officinalis at different growth ages, and the functional annotation of the AP2/ERF gene family in the bark was performed to find the changes in expression. This will have significant practical value in the genetic improvement and breeding of Magnolia officinalis. These findings will also serve as the foundation for further investigation into the function of the AP2/ERF gene family.

2.1 Plant Materials and Data Sources

The experimental material was ‘Chuan Hou Po’ bark from Magnolia officinalis Rehd. et Wils., grown in Sichuan Province. Samples were collected from dried stem bark from ten-year-old (DR) and two-year-old (XR) Magnolia officinalis trees in Wahugou Village, Beichuan Qiang Autonomous County, Mianyang City, Sichuan Province (Coordinates: 31°58′46.38″ N, 104°30′39.00″ E). Trees were categorized depending on age. Three trees per age group (DR: DR1, DR2, DR3; XR: XR1, XR2, XR3) were sampled to create biological duplicates.

The stem epidermis of Magnolia officinalis Cortex was frozen in liquid nitrogen and delivered to Major Biotechnology Co., Ltd. for second-generation transcriptome sequencing. After removing junctions and low-quality readings, clean data was generated. According to the scaffold-level Magnolia officinalis Cortex genome sequence provided by Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, the full coding gene sequence of Magnolia officinalis Cortex was obtained via sequence splicing and annotated in the database. The NCBI gene database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/, accessed on 07 June 2025) was utilized to collect protein sequence data for Magnolia officinalis. 135 Arabidopsis AP2/ERF protein sequences were obtained from the TAIR database (https://www.arabidopsis.org/index.jsp, accessed on 07 June 2025).

2.2 Identification of Magnolia officinalis AP2/ERF Gene Family Members

The protein sequences of Magnolia officinalis were examined and evaluated using the local BLAST software against those of 135 Arabidopsis AP2/ERF gene family members. To identify high-reliability candidate sequences, we used the following criteria: E-value < 1 × 10−10, comparison score > 100, and a single terminator. Second, the information acquired in the previous stage is summarized, duplicate data is deleted, and redundant sequences are eliminated. The possible AP2/ERF sequence is next examined to check if it contains the totally preserved AP2 domain using the SMART online software (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/, accessed on 07 June 2025) and the InterProScan online software. The discovered protein sequence, which comprised one or two conserved AP2 domains, was retained and identified as the AP2/ERF gene family of Magnolia officinalis. Furthermore, these AP2/ERF gene families were categorized based on the conserved AP2 domains of the AP2/ERF gene subfamily.

Protparam (https://www.expasy.org/resources/protparam, accessed on 07 June 2025) was used in the online analysis software Expasy to determine the length of the encoded amino acid, the total number of positive and negative charge residues, molecular weight (MW), theoretical isoelectric point (pI), wobble factor, aliphatic index, and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY). The subcellular localization of the Magnolia officinalis AP2/ERF protein sequence was then carried out utilizing the web platform Cell-PLoc 2.0 (Plant-mPLoc, http://www.csbio.sjtu.edu.cn/bioinf/Cell-PLoc-2/, accessed on 07 June 2025).

2.3 Phylogenetic Analysis, Motif Analysis, and Structure Prediction of AP2/ERF Gene Family Members in Magnolia officinalis

The 135 Arabidopsis AP2/ERF protein sequences, as well as the previously reported Magnolia officinalis AP2/ERF gene family protein sequences, were loaded into MEGA11.0 software to create a phylogenetic tree. After importing all of the sequences, Align by ClustalW was used for multiple sequence alignment, and the Neighbor-Joining method was used to build the phylogenetic tree of the Magnolia officinalis AP2/ERF and Arabidopsis AP2/ERF gene families. The AP2/ERF protein motif was predicted using the internet software MEME (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme, accessed on 07 June 2025). The number of motif predictions was fixed to ten, with a minimum length of six amino acids and a maximum of fifty.

The Prabi (https://npsa-prabi.ibcp.fr/cgi-bin/npsa_automat.pl?page=npsa_sopma.html, accessed on 07 June 2025) was used to access the secondary structure prediction module, and SOPMA was selected to predict the secondary structure of the Magnolia officinalis AP2/ERF protein. The AP2/ERF protein sequence of Magnolia officinalis was analyzed using the SWISS-MODEL online software (https://www.swissmodel.expasy.org, accessed on 07 June 2025). The model was created using the database template with the greatest resemblance, and the tertiary structure of the Magnolia officinalis AP2/ERF protein was determined.

2.4 Analysis of Gene Expression Levels of Magnolia officinalis AP2/ERF Gene Family in Different Growth Periods

Magnolia officinalis RNA-Seq data (relevant data can be found in Supplementary Materials) from our previous study were divided into two groups: Magnolia officinalis at mature growth (DR1, DR2, DR3) and Magnolia officinalis at early growth (XR1, XR2, XR3). The gene expression of the AP2/ERF gene family in Magnolia officinalis was examined during the two groups’ respective growth periods, and a heatmap tree was created. The AP2/ERF genes that were overexpressed in the two groups were annotated in GO (https://www.geneontology.org/) and KEGG (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/, accessed on 07 June 2025).

2.5 Structure and Function Prediction of Differential Genes in the AP2/ERF Gene Family of Magnolia officinalis

The gene-level expression data were used in shapiro.test() and levene Test() to perform a normal distribution test and a homogeneity of variance test in R. When the test results showed normal distribution (p-value > 0.05) and homogeneity of variance (p-value > 0.05), t.test() was used; otherwise, wilcox.test() was used to obtain two groups of Magnolia officinalis AP2/ERF genes with significant difference (p-value < 0.05) in expression during different growth periods. These differential genes were phylogenetically matched with AP2/ERF homologous genes similar to Arabidopsis thaliana, and structural and functional prediction analysis was performed using the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database (https://alphafold.com).

3.1 Identification of MoAP2/ERF Gene Family

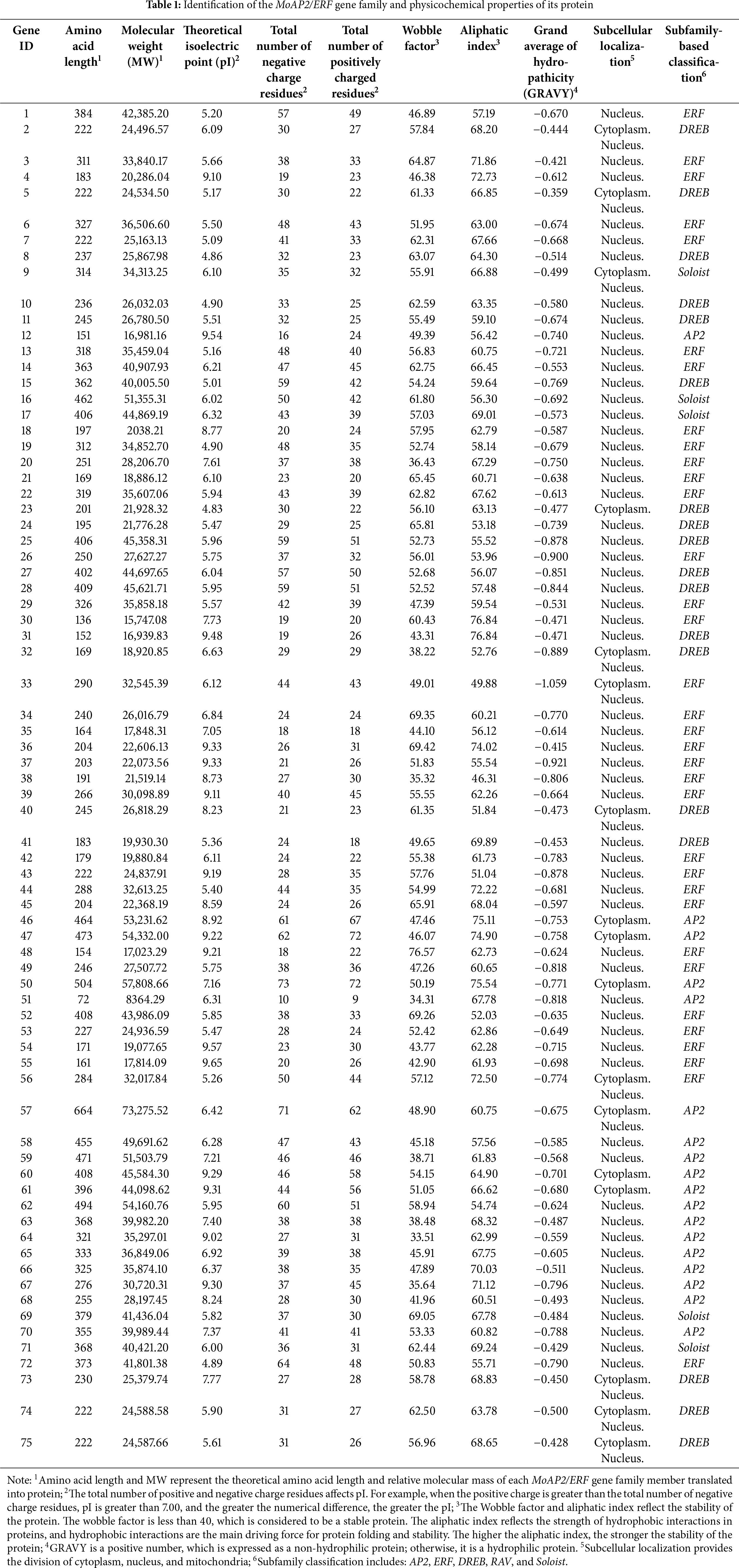

The protein sequence of Magnolia officinalis was compared to the protein sequence of 135 members of the AP2/ERF gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana, yielding 11553 protein sequences. After the information summary, we deleted repetitive items, sequences with E-values larger than 1 × 10−10, and those with comparison scores less than 100. Following that, 89 protein sequences were retrieved, and proteins with two or more terminators and the same protein sequence were excluded. The protein sequence containing the AP2 domain was tested for redundancy using the SMART network online tools. 75 AP2/ERF sequences with the AP2 domain were identified and called MoAP2/ERF1–MoAP2/ERF75. The 75 MoAP2/ERF1–MoAP2/ERF75 were divided into 4 subfamilies (Table 1): 18 AP2 members (2 AP2 domains) [33], 5 Soloist members (AP2 conserved domains have more differences) [13], 18 DREB members (1 AP2 domain; the 14th and 19th amino acids are valine and glutamic acid, respectively) and 34 ERF members (1 AP2 domain; the 14th and 19th amino acids are alanine and aspartic acid, respectively) [34,35]. There was no B3 domain found in the AP2/ERF gene family of Magnolia officinalis reported in this study, implying that no AP2/ERF gene belonged to the RAV subfamily [36].

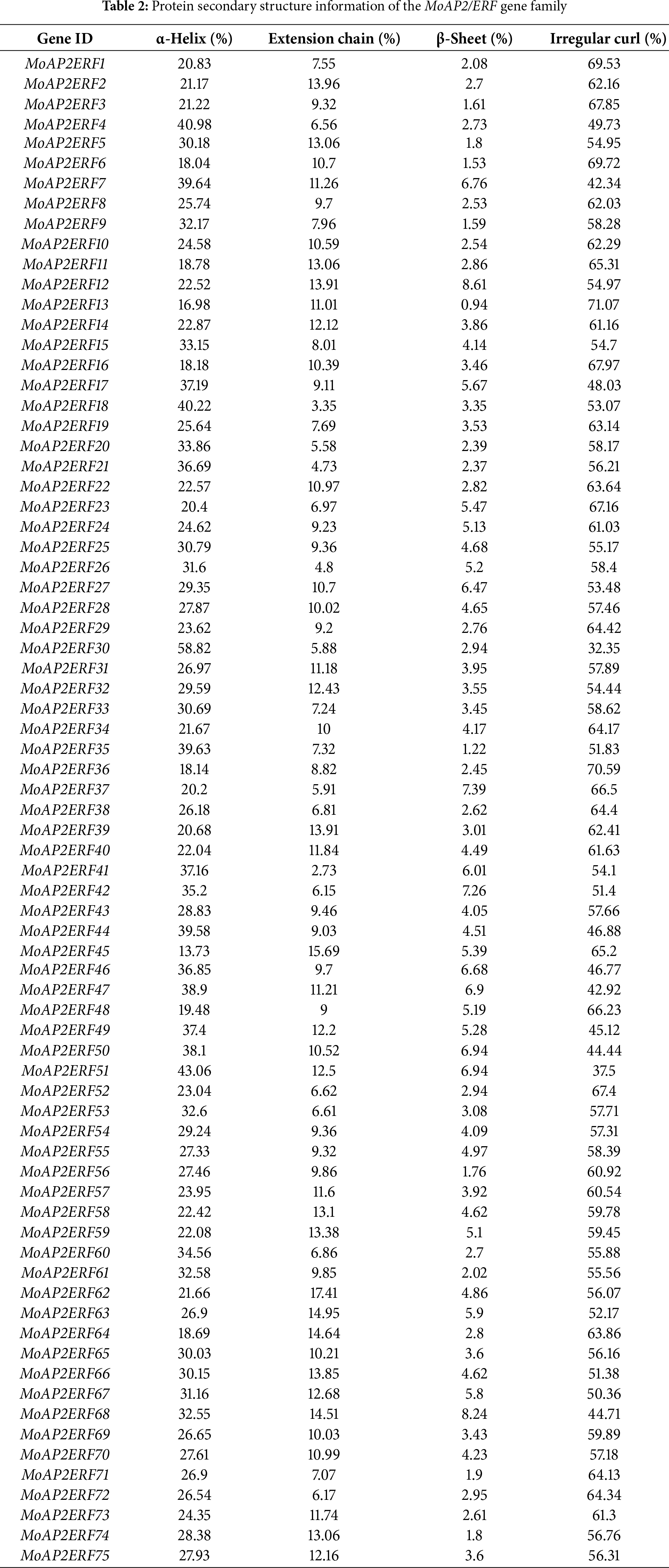

We used Expasy to determine the physicochemical parameters of these 75 MoAP2/ERF protein sequences (Table 1). The results revealed that the amino acid chain length of most MoAP2/ERF proteins ranged from 72 to 664 aa, with an average of 306 aa and an average relative molecular weight of around 33,779.84 Da. MoAP2/ERF51 has the smallest amino acid length of 72 aa, whereas MoAP2/ERF57 has the greatest amino acid length of 664 aa, despite being members of the same AP2 subfamily. This demonstrates that the length and size of AP2/ERF gene family proteins in Magnolia officinalis vary greatly. The theoretical isoelectric point of the MoAP2/ERF protein is 4.83–9.65, indicating a large degree of variability in the acid-base range. The proportion of theoretical isoelectric points less than 7.00 is relatively high, about 62% (29), indicating that the number of acidic MoAP2/ERF proteins is greater than that of alkaline MoAP2/ERF proteins, and most of the DREB subfamily proteins are acidic (except MoAP2/ERF31, MoAP2/ERF40, and MoAP2/ERF73). In terms of the protein stability study, practically all proteins had an instability coefficient of more than 40, indicating that they were unstable, with only 9 MoAP2/ERF proteins remaining stable. The protein aliphatic index ranged between 46.31 and 76.84. The total average hydrophilicity of the MoAP2/ERF proteins was negative, and they were all hydrophilic. Using subcellular localization results (Table 1), MoAP2/ERF proteins were primarily localized in the nucleus (56), with a minor number of proteins localized in the cytoplasm (6) and others able to shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm (13). It can be seen that the MoAP2/ERF gene family is primarily found in the nucleus and performs an active function.

3.2 Phylogenetic Analysis, Motif Analysis, and Structure Prediction of MoAP2/ERF Gene Family

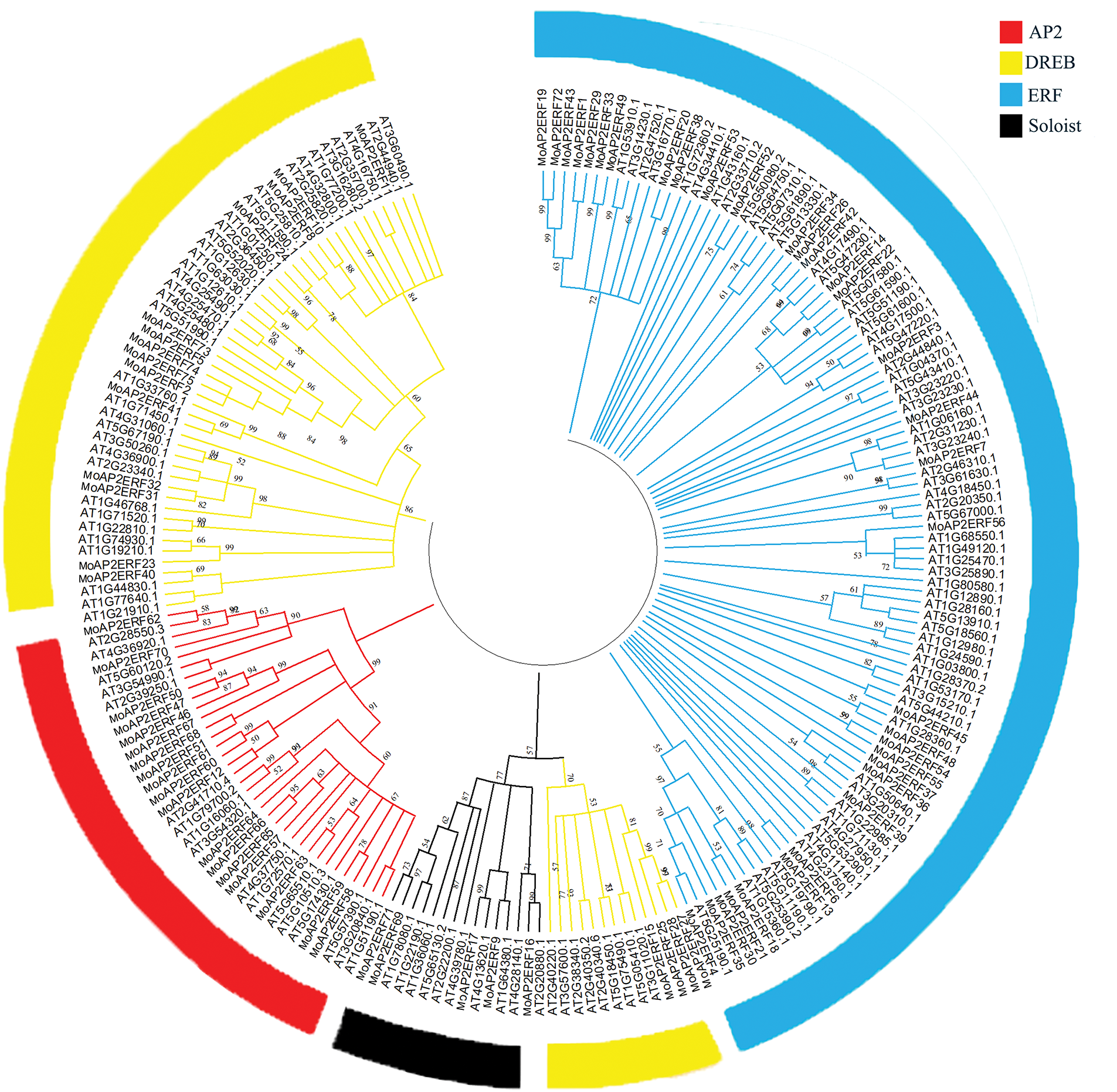

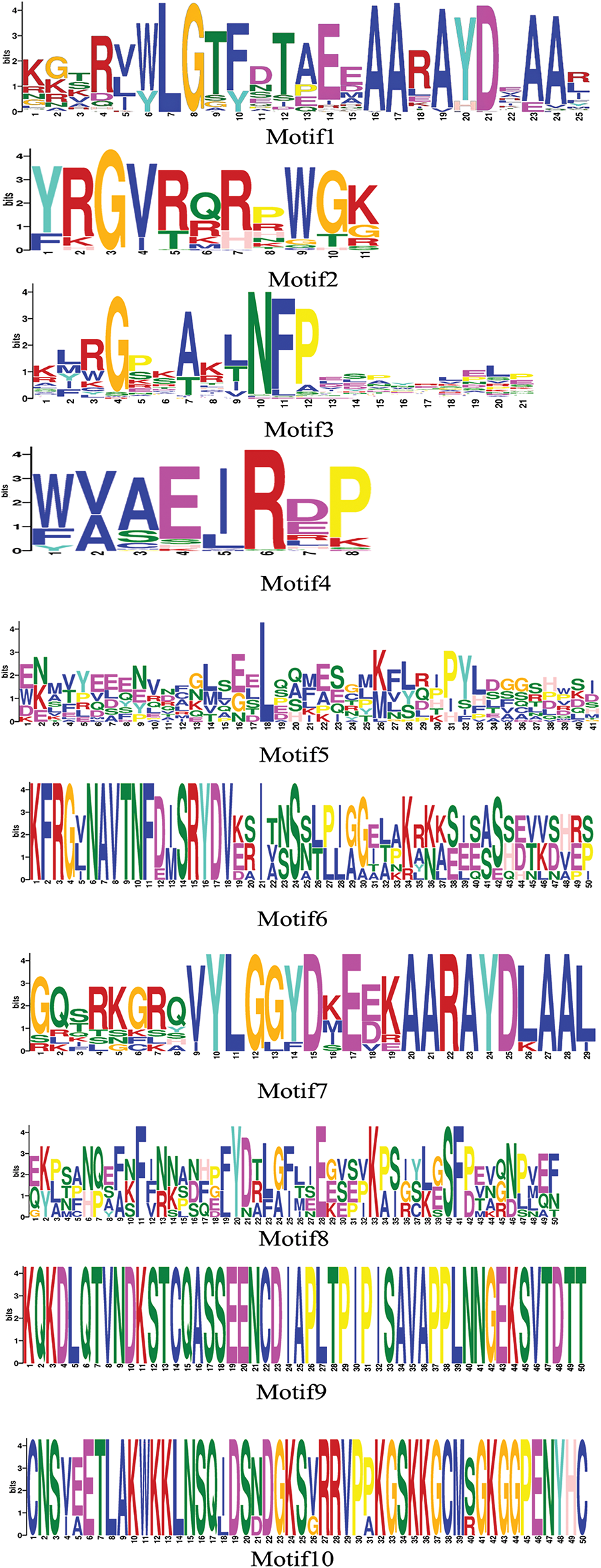

To generate a neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree, the MoAP2/ERF protein sequence was compared to the AP2/ERF protein sequence of the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana using MEGA11.0 software (Fig. 1). The results indicated that the phylogenetic tree was divided into four subfamilies: AP2, Soloist, ERF, and DREB. MoAP2/ERF in the ERF subfamily and AP2/ERF in Arabidopsis thaliana have additional branches, showing that these ERF subfamilies’ activities are complex and changeable. Furthermore, we identified that one branch of the DREB subfamily (which includes MoAP2/ERF15, MoAP2/ERF25, MoAP2/ERF27, and MoAP2/ERF28) would be more comparable to the Soloist subfamily during differentiation. The online analytic software MEME was used to predict and analyze the conserved motifs in the MoAP2/ERF protein sequence, and the results are shown in the Figs. 2 and 3. Almost all MoAP2/ERF protein sequences contain Motif1, Motif2, Motif3, and Motif4. These are processed via α-helix, β-sheet, extension, and random coil to form the conserved AP2 domain. The AP2 domain is formed in the following order: Motif 2, Motif 4, Motif 1, and Motif 3, followed by Motifs 8 and 5. In addition to the AP2 domain, the conserved motifs show that the majority of MoAP2/ERF proteins are extremely conserved. Their delicate structure and high amount of differentiation make other amino acid sites less predictable.

Figure 1: The phylogenetic tree formed by MoAP2/ERF and AP2/ERF of Arabidopsis thaliana

Figure 2: Logo of the MoAP2/ERF sequence

Figure 3: Conservative motif of the MoAP2/ERF sequence

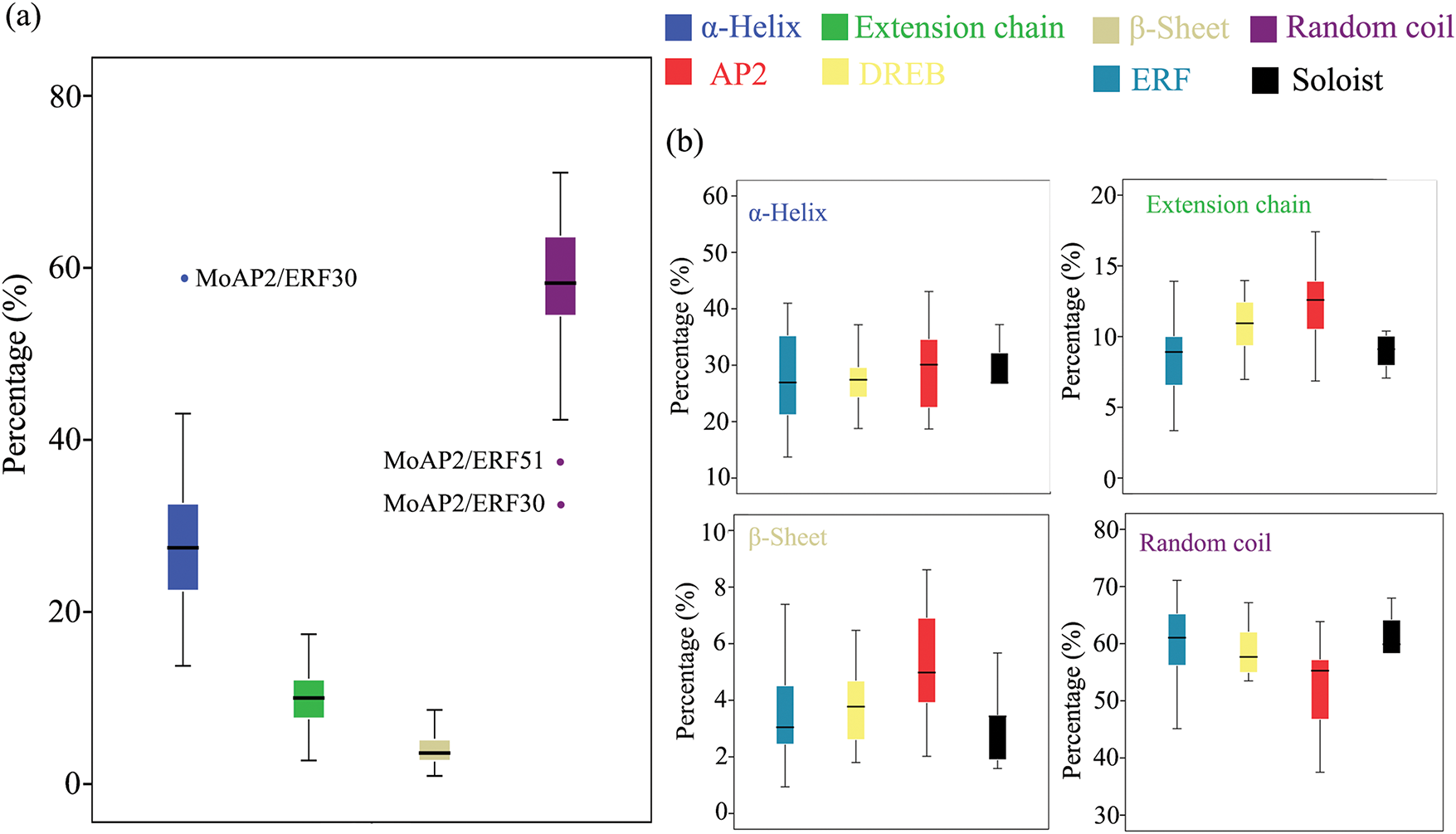

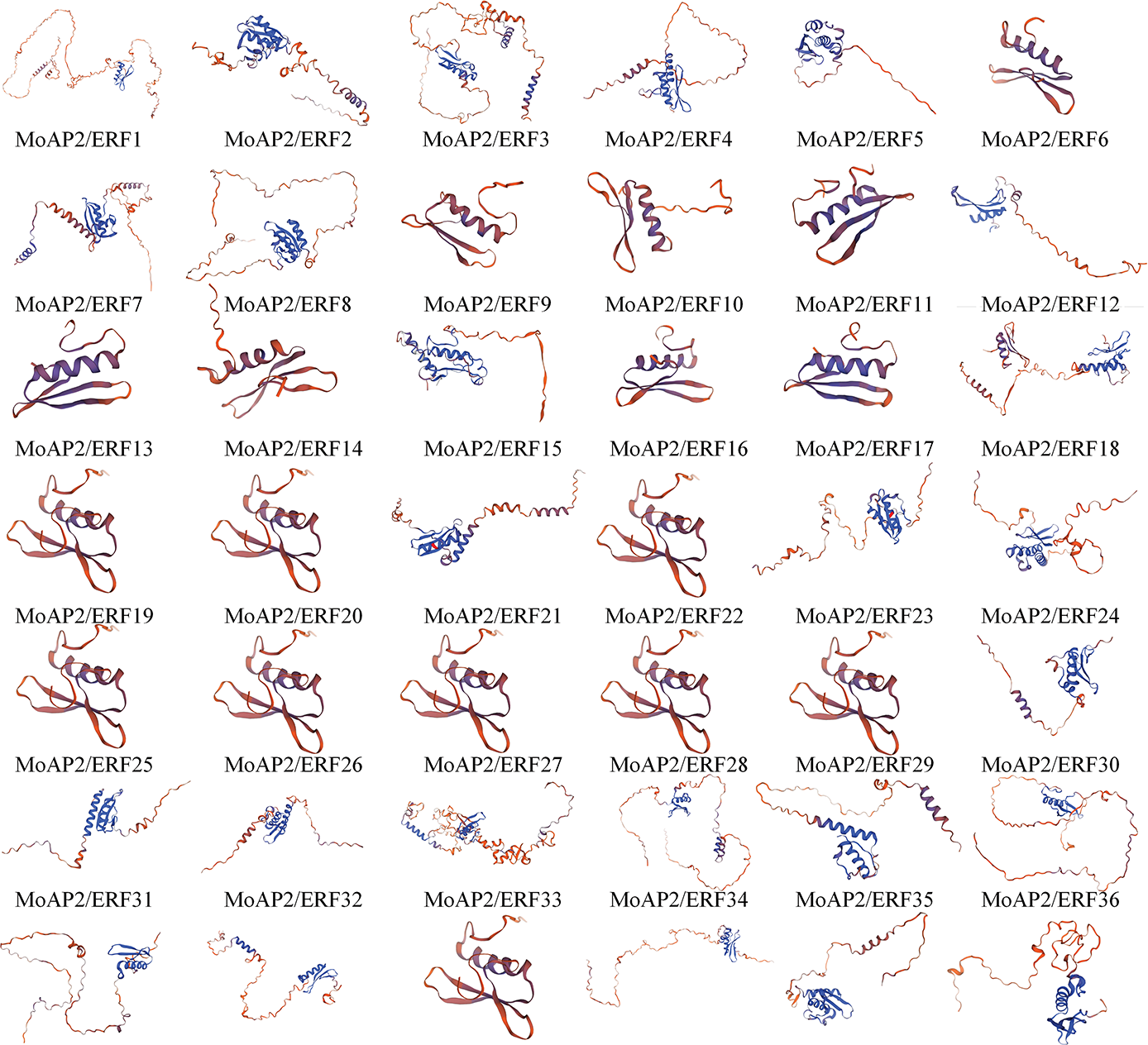

Plants’ AP2/ERF domain consists of three anti-parallel β-sheets, a parallel α-helix, and random coils [37]. The MoAP2/ERF gene family’s secondary structure prediction (Table 2) and structural difference analysis (Fig. 4) identified numerous α-helix and random coil proteins. MoAP2/ERF30 contains a substantial amount of α-helix, with the rest ranging from 20.00% to 40.00%, indicating a highly conserved AP2 domain. The fraction of irregular curls spans from 32.35% to 71.07% and is the largest. Furthermore, the proportion of random coils in MoAP2/ERF30 and MoAP2/ERF51 is low, indicating that MoAP2/ERF30 has a more conservative and regular secondary structure. The proportion of β-sheets was the least, whereas long chains were concentrated in 2.73%–17.41%. The majority of MoAP2/ERF gene family proteins in the SWISS-MODEL online model have a Seq-identity of at least 70%. Seven MoAP2/ERF gene family proteins share the ERF structural model of Gcc-box binding. There are 32 ethylene-responsive transcription factors or ERF crystal structure models, 31 AP2/ERF-related protein models, and CBF-like transcription factor models (Fig. 5).

Figure 4: MoAP2/ERF protein secondary structure (a). Comparison of the MoAP2/ERF subfamily on four secondary structures (b)

Figure 5: Tertiary structure of MoAP2/ERF protein

3.3 Analysis of Gene Expression Level of MoAP2/ERF Gene Family in Magnolia officinalis at Different Growth Periods

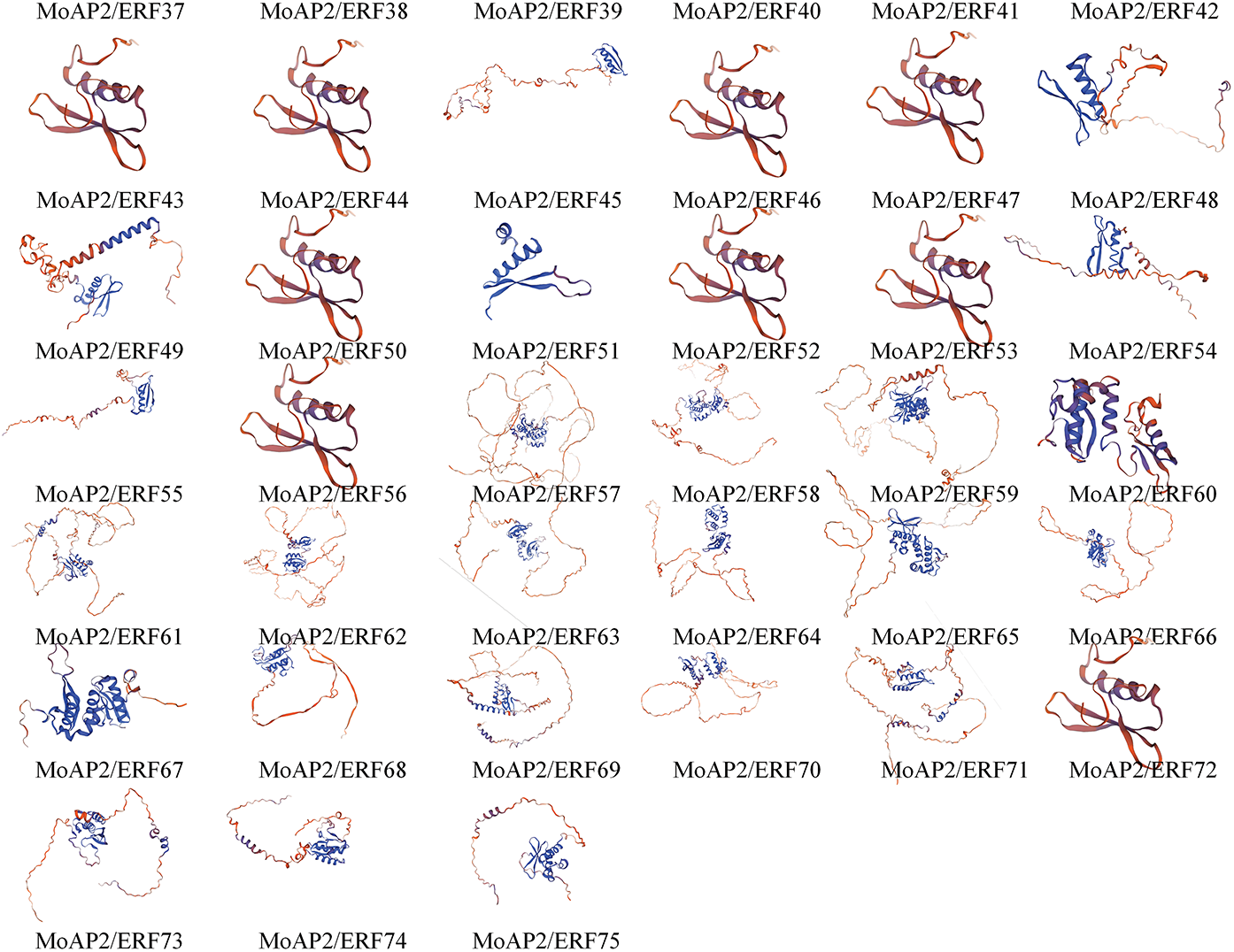

The heatmap tree of 75 MoAP2/ERF gene families was constructed in the order of DREB to ERF utilizing the gene expression levels of Magnolia officinalis throughout the early growth period (XR1, XR2, XR3) and the mature growth period (DR1, DR2, DR3) (Fig. 6). MoAP2/ERF31 and MoAP2/ERF32, which share a high degree of similarity, were overexpressed in all samples. The expression of MoAP2/ERF genes was higher in XR than in DR. MoAP2/ERF62 and MoAP2/ERF70, with substantial homology, as well as the last secondary branch, MoAP2/ERF66–MoAP2/ERF58, demonstrated that XR expression was higher than that of DR. Additionally, MoAP2/ERF71 and MoAP2/ERF69 of the Soloist subfamily have obvious expression ability on XR and DR. In the ERF subfamily, there are more active AP2/ERF genes, such as MoAP2/ERF39, MoAP2/ERF36, MoAP2/ERF37, MoAP2/ERF55, MoAP2/ERF45, MoAP2/ERF56, MoAP2/ERF60, MoAP2/ERF22, MoAP2/ERF20, MoAP2/ERF1, and MoAP2/ERF43, which are substantially expressed in both DR and XR.

Figure 6: MoAP2/ERF transcriptome expression heatmap tree. In the DREB and AP2 subfamily (a). In the Soloist and ERF subfamily (b)

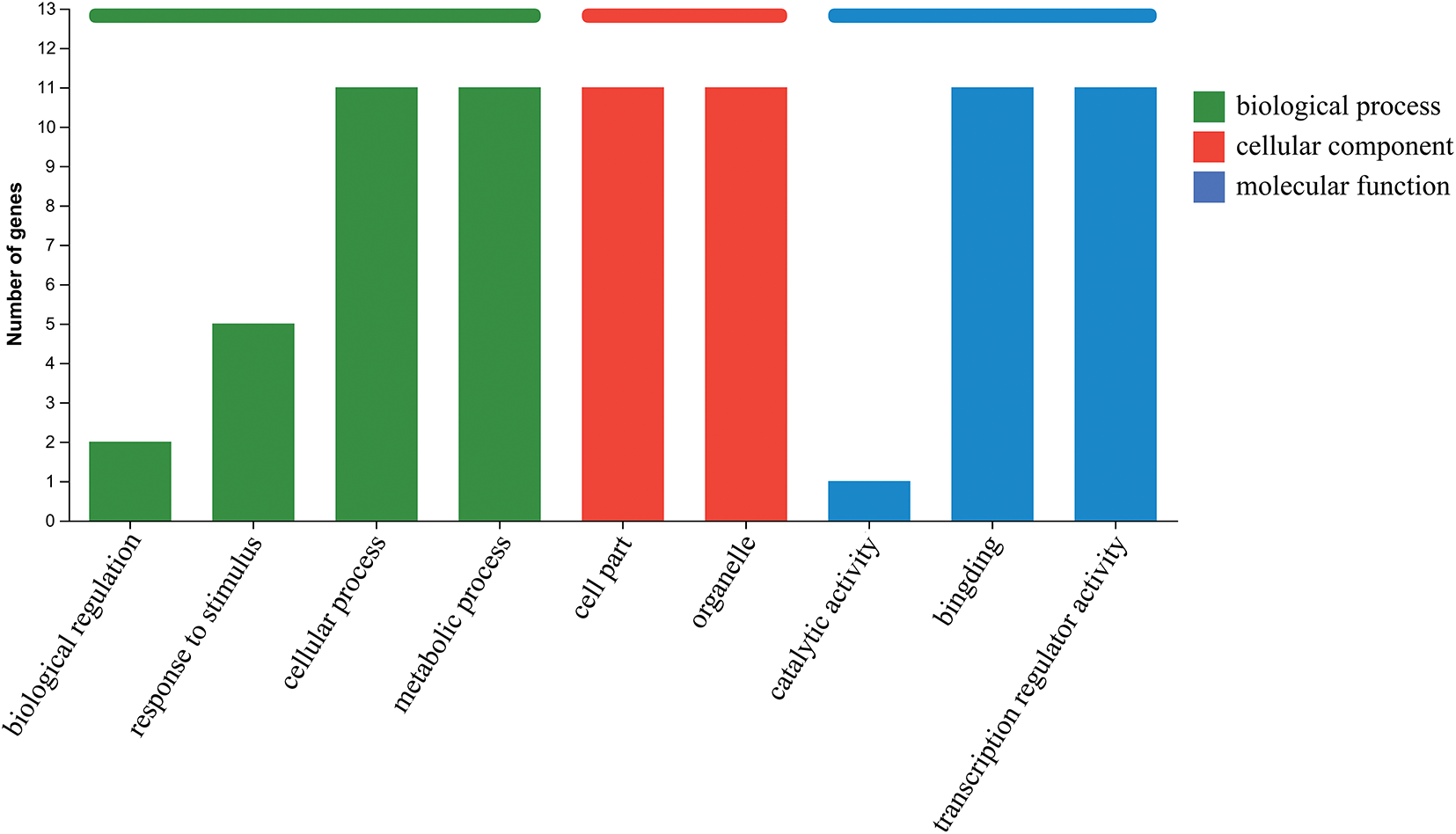

We performed GO and KEGG functional annotations on these 15 highly expressed MoAP2/ERF genes and found functional classifications for 11 of them in the GO database, including biological process, cellular component, and molecular function (Fig. 7). Among these, MoAP2/ERF22 and MoAP2/ERF1 play biological regulatory roles. MoAP2/ERF22, MoAP2/ERF60, MoAP2/ERF32, MoAP2/ERF71, and MoAP2/ERF1 are all responsive to stimuli. MoAP2/ERF55 can activate imidazole glycerol phosphate synthase, which is involved in histidine biosynthesis. In vivo, MoAP2/ERF39 acts as a transcriptional activator for Pti6, causing the activation of multiple PR genes with the GCC-box and performing a critical and unique function in plant defense.

Figure 7: Functional classification of 11 MoAP2/ERF gene family members was performed

3.4 The Structure and Function Prediction of Differential Genes in the MoAP2/ERF Gene Family

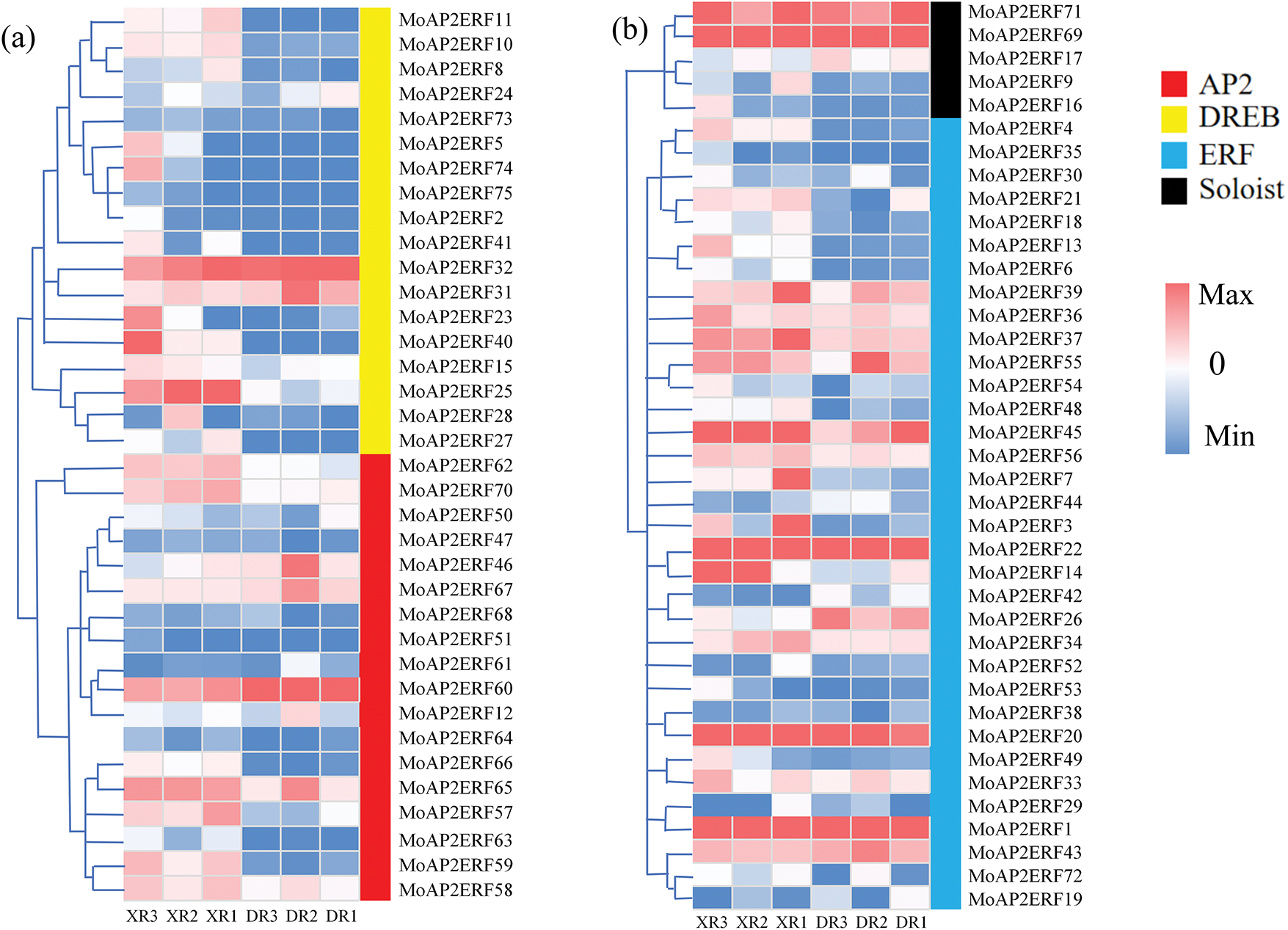

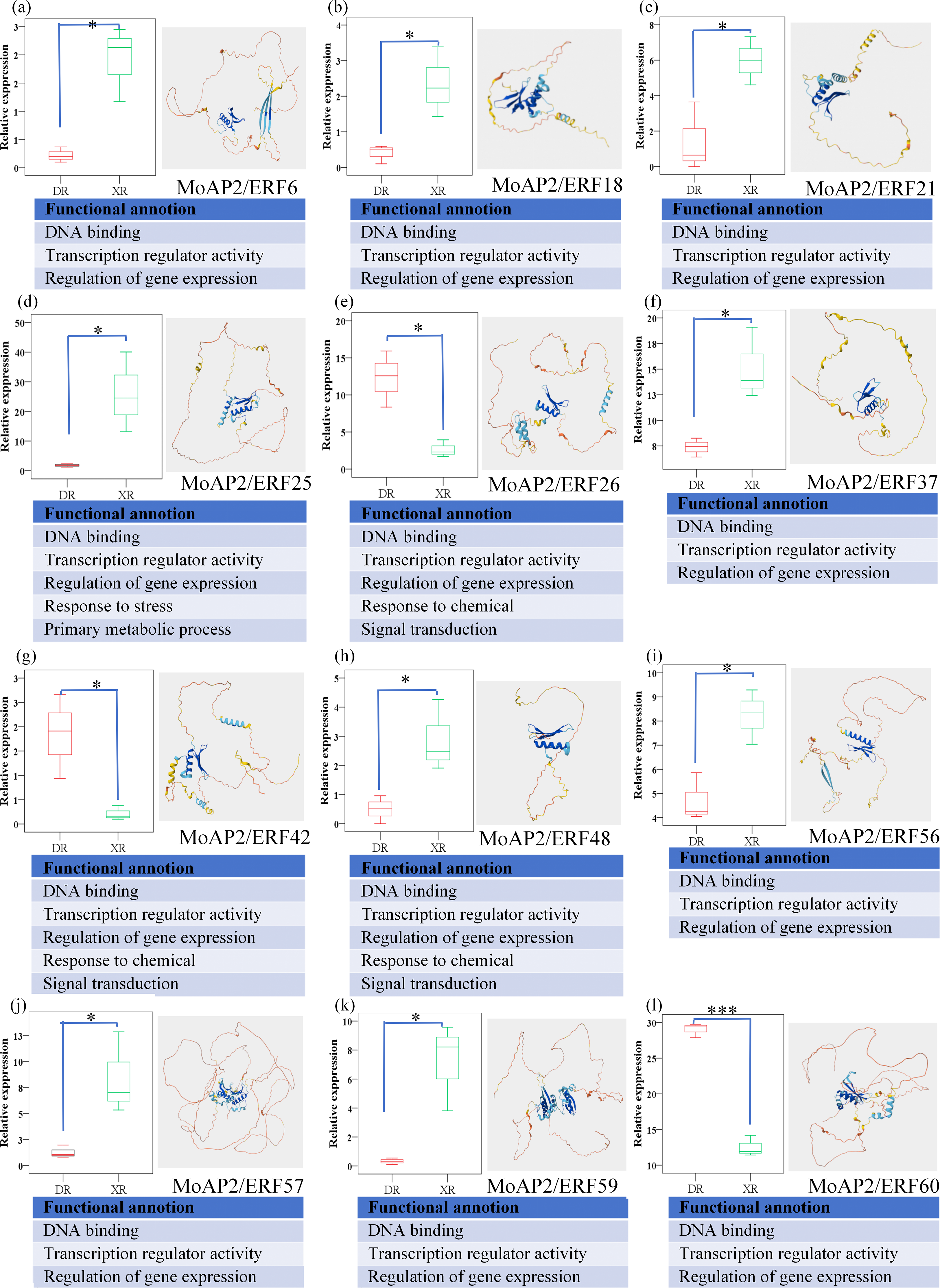

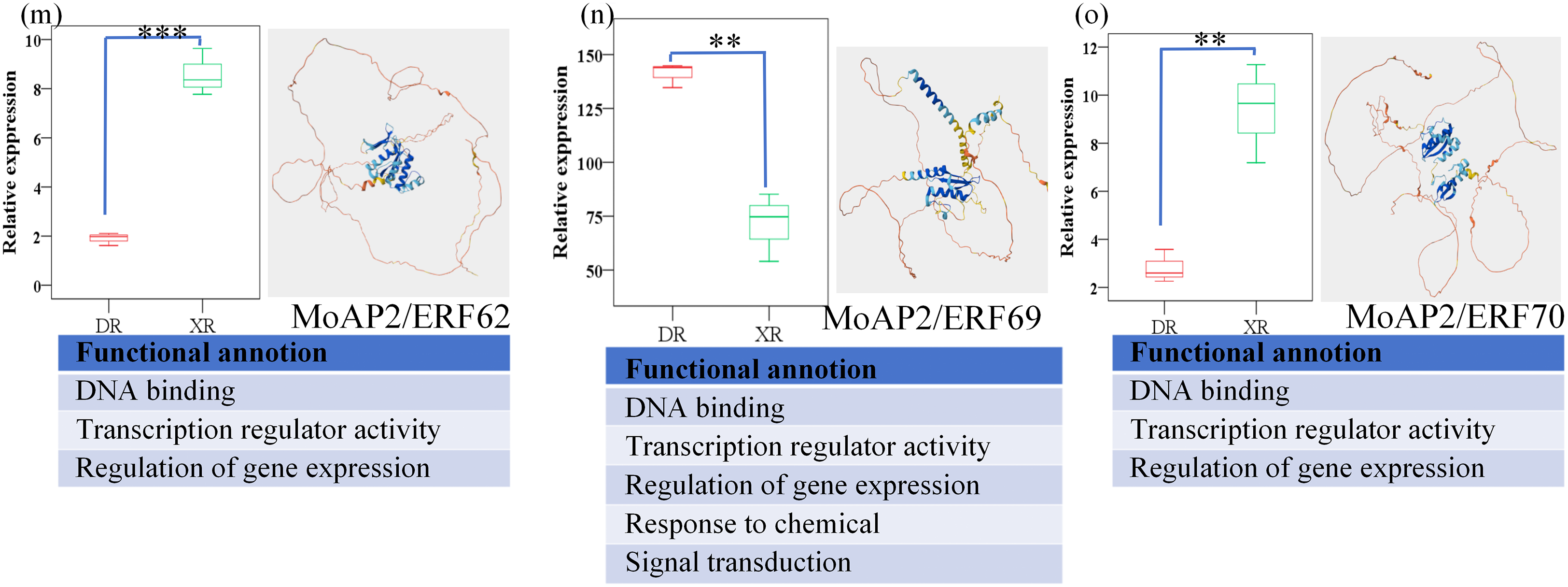

We examined the gene expression levels of the MoAP2/ERF gene family throughout two growth periods (XR and DR) and discovered 15 substantially changed genes (Fig. 8). Ten of these differentially expressed genes have three functions: DNA binding, transcription regulator activity, and gene expression control, with the remaining five also involved in stress response and primary metabolic processes. This suggests that they often influence Magnolia officinalis gene expression by binding to DNA, affecting the plant’s ability to tolerate adverse environmental variables and create secondary metabolites. In some areas, XR may outperform DR.

Figure 8: Structure and function prediction analysis of 15 MoAP2/ERF gene family members. The 15 MoAP2/ERF gene family members are MoAP2/ERF6 (a), MoAP2/ERF18 (b), MoAP2/ERF21 (c), MoAP2/ERF25 (d), MoAP2/ERF26 (e), MoAP2/ERF37 (f), MoAP2/ERF42 (g), MoAP2/ERF48 (h), MoAP2/ERF56 (i), MoAP2/ERF57 (j), MoAP2/ERF59 (k), MoAP2/ERF60 (l), MoAP2/ERF62 (m), MoAP2/ERF69 (n), and MoAP2/ERF70 (o), respectively. In the model structure, dark blue indicates very high confidence (pLDDT > 90), light blue indicates confidence (90 > pLDDT > 70), yellow indicates low confidence (70 > pLDDT > 50), and orange indicates very low confidence (pLDDT < 50). Among them, “*” means p < 0.05, “**” means 0.01 < p < 0.05, and “***” means p < 0.01

The identification of plant gene families is the basis for the systematic study of the biological functions of family members. In this regard, information on the AP2/ERF gene family members of Magnolia officinalis is limited. A total of 75 members of the AP2/ERF gene family of Magnolia officinalis were identified. The 75 MoAP2/ERF1–MoAP2/ERF75 genes were classified based on their conserved AP2 domains from the AP2/ERF gene subfamily. The Magnolia officinalis AP2/ERF gene family was revealed to have four branches: DREBs (18), AP2s (18), Soloists (5), and ERFs (34). This is less than the number of AP2/ERF genes identified in general crops, probably because Magnolia officinalis is a woody plant of Magnoliaceae, which is different from the usual crops [9]. This also makes it difficult to explore the function of the AP2/ERF gene family of Magnolia officinalis. The MoAP2/ERF gene family proteins are hydrophilic, with a wide range of pI. The AP2 domain is formed in the order of motifs Motif2, Motif4, Motif1, Motif3, Motif8, and Motif5, and is formed by polymerization, such as α-helix. This indicates that the AP2/ERF gene family of Magnolia officinalis is highly conserved during evolution, as in other plants [38]. The MoAP2/ERF gene family proteins are mainly localized in the nucleus. A small number of proteins are localized in the cytoplasm, which is similar to the localization results of the AP2/ERF gene family of the medicinal plant Lithospermum erythrorhizon [39], indicating that the family binds to DNA and plays a role in the downstream transcription process, suggesting that it has a wider range of functions.

The part of the MoAP2/ERF genes is classified as dehydration-responsive element-binding proteins, which are primarily engaged in the response to environmental challenges such as abscisic acid (ABA), drought, and low temperature [40]. Overexpression of the DREB subfamily increases Magnolia officinalis’ tolerance to osmotic, high salt, and cold stresses [41]. The identified MoAP2/ERF31 and MoAP2/ERF32 were significantly expressed compared with other MoAP2/ERF genes in the DREB subfamily, and the results of Magnolia denudata and Magnolia wufengensis in the same family as Magnolia showed that AP2/ERF genes play an important role in cold [42,43]. Therefore, we speculate that these two genes may be used as key trans-activators to participate in or control the regulation of crop growth and adaptation to cold environments, including Magnolia officinalis. In addition, we noticed that the DREB subfamily members of Magnolia officinalis were more active during the growth of young age, suggesting that the ability of abiotic stress was better. This reflects the positive role of the DREB subfamily in combating abiotic stresses [44]. The AP2 subfamily’s primary function is to regulate the development of flowers, seeds, and ovules, as well as the accumulation of seed oil and protein [45]. Magnolia officinalis has a high seed oil content and is closely connected to the AP2 subfamily. At lower altitudes, saplings grow quickly while adult trees grow slowly, and at higher elevations, the converse occurs. The Magnolia officinalis used in this study was found in Wahugou Village, approximately 1500 m above sea level. The expression of the AP2 subfamily is low, particularly in adult trees. In addition, MoAP2/ERF60 in the AP2 subfamily is active at all growth periods, which we think may be related to the differentiation of flower buds [46]. MoAP2/ERF71 and MoAP2/ERF69 of the Soloist subfamily have high expression ability in Magnolia officinalis, indicating that they play an important role. The ERF subfamily is not only involved in the response to biotic stresses such as ethylene and pathogens [47], but it can also regulate the biosynthesis of secondary metabolism in Magnolia officinalis. Some researchers screened the ERF subfamily gene LTF1 with a conserved AP2 domain and discovered that LTF1 activates genes in the lignan synthesis pathway, boosting lignan accumulation [48]. Magnolia officinalis ERF subfamily has numerous branches and has significant expression. It is thought that it may interact with small molecular compounds or bacteria in its own environment, causing up-regulation through mutual coordination, so enhancing Magnolia officinalis tolerance.

A number of studies have shown that the AP2/ERF gene family is associated with plant development and external stress [49,50]. By analyzing the expression of the MoAP2/ERF gene family, we found that most genes were highly expressed in the early growth period of Magnolia officinalis, suggesting that these genes play an important role in the growth and development of Magnolia officinalis. Magnolia officinalis XR has stronger environmental stress than DR, such as the significant difference in the gene MoAP2/ERF62, implying that Magnolia officinalis has a high tolerance level during the rapid growth of the early period in order to resist potential adverse factors of the external environment. Notably, we discovered that 15 members of the MoAP2/ERF gene family exhibit a diverse variety of physiological activities in biological processes, cellular components, and molecular function. Among them, MoAP2/ERF55 can catalyze the action of imidazoglycerophosphate synthase in histidine biosynthesis, whereas MoAP2/ERF39 (transcription activator Pti6) can regulate the expression of the PR gene in response to plant pathogen invasion. Further studies are needed to understand the role of these 15 MoAP2/ERF genes in this regard. In addition, by analyzing the differential genes of the MoAP2/ERF gene family at different growth periods, there were 15 significantly different MoAP2/ERF genes. We observed that in the XR period of Magnolia officinalis, the MoAP2/ERF6, MoAP2/ERF18, MoAP2/ERF21, MoAP2/ERF25, MoAP2/ERF37, MoAP2/ERF48, MoAP2/ERF56, MoAP2/ERF57, MoAP2/ERF59, MoAP2/ERF62, and MoAP2/ERF70 genes are more active and can bind cis-elements such as the GCC-box and DRE/CRT to regulate DNA transcription and further affect more other gene expression. With the continuous growth and development of Magnolia officinalis, Magnolia officinalis is in the DR period, and MoAP2/ERF26, MoAP2/ERF42, and MoAP2/ERF69, in response to chemical function, begin to express actively, indicating that the metabolic process of Magnolia officinalis begins to accelerate. Including may be related to the biosynthesis of Magnolia’s effective substances. This further indicates that the AP2/ERF gene family can regulate plant secondary metabolism, similar to the saponin biosynthesis of the medicinal plant Gynostemma pentaphyllum, which is affected by the AP2/ERF gene [51]. It is suggested that these three MoAP2/ERF genes are related to the rapid accumulation of medicinal substances during the growth and maturation of Magnolia officinalis and need to be continuously explored in the future.

This is the first comprehensive study of the AP2/ERF gene family in Magnolia officinalis, aiming to help elucidate gene function and expression patterns. In this study, based on the transcriptome sequencing data of Magnolia officinalis, 75 MoAP2/ERF genes and their protein sequences were identified, and the physicochemical properties, conserved motifs, multi-dimensional structures, and expression profiles of their proteins at different growth periods were determined. The expression of more DREB and ERF subfamily genes can make Magnolia officinalis grow under abiotic stresses such as cold, especially in the early growth of Magnolia officinalis. In addition, we found that 15 MoAP2/ERF genes were strongly expressed, such as MoAP2/ERF55, which promotes histidine biosynthesis, and MoAP2/ERF39, which regulates PR gene expression. Furthermore, the functions of 15 MoAP2/ERF genes with significant expression differences were analyzed, and it was found that the MoAP2/ERF genes involved in metabolism began to be up-regulated at the mature growth period. These results should provide an opportunity to understand the role of Magnolia officinalis in response to abiotic stress and metabolic synthesis. It also provides potential candidate genes that can be further explored through gene editing, etc., in order to breed Magnolia officinalis varieties with resistance to abiotic stress and promotion of secondary metabolism.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (number 81202933), the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (number 2025ZNSFSC0205 and number 2022NSFSC0592), and the Science and Technology Plan Project of Mianyang City (number 2018YFZJ025).

Author Contributions: All the authors listed have contributed to this work and approved it for publication. Hui Tian and Yuanyuan Zhang conceived and designed the experiments. Qian Wang, Yuanyuan Zhang and Mingxin Zhong performed the experiments. Mingxin Zhong, Xinlei Guo and Bainian Zhang analyzed the data. Yuanyuan Zhang, Chengjia Tan, Zhuo Xu, Daren Feng, Zhenpeng Xi, Hui Tian, Qian Wang and Xin Hu provided relevant professional knowledge. Mingxin Zhong and Qian Wang wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Materials. The protein sequence of MoAP2ERF was provided in Supplementary Text S1. The gene sequence of MoAP2ERF was provided in Supplementary Text S2. The CDS sequence of MoAP2ERF was provided in Supplementary Text S3. Test code for significant difference is provided in Supplementary Text S4. The expression data of MoAP2ERF gene in Magnolia officinalis was provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Ethics Approval: No part of this research involved human or animal samples.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.070560/s1.

References

1. National Pharmacopoeia Commission. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China: volume I. Beijing, China: Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Press; 2020. 263 p. [Google Scholar]

2. Rauf A, Patel S, Imran M, Maalik A, Arshad MU, Saeed F, et al. Honokiol: an anticancer lignan. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;107:555–62. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2018.08.054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Hu M, Jiang W, Ye C, Hu T, Yu Q, Meng M, et al. Honokiol attenuates high glucose-induced peripheral neuropathy via inhibiting ferroptosis and activating AMPK/SIRT1/PGC-1α pathway in Schwann cells. Phytother Res. 2023;37(12):5787–802. doi:10.1002/ptr.7984. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Kim SY, Kim J, Jeong SI, Jahng KY, Yu KY. Antimicrobial effects and resistant regulation of magnolol and honokiol on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:283630. doi:10.1155/2015/283630. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Lee J, Jung E, Park J, Jung K, Lee S, Hong S, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of magnolol and honokiol are mediated through inhibition of the downstream pathway of MEKK-1 in NF-kappaB activation signaling. Planta Med. 2005;71(4):338–43. doi:10.1055/s-2005-864100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Shen JL, Man KM, Huang PH, Chen WC, Chen DC, Cheng YW, et al. Honokiol and magnolol as multifunctional antioxidative molecules for dermatologic disorders. Molecules. 2010;15(9):6452–65. doi:10.3390/molecules15096452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Lee JH, Jung JY, Jang EJ, Jegal KH, Moon SY, Ku SK, et al. Combination of honokiol and magnolol inhibits hepatic steatosis through AMPK-SREBP-1 c pathway. Exp Biol Med. 2015;240(4):508–18. doi:10.1177/1535370214547123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Yuan Y, Zhou X, Wang Y, Wang Y, Teng X, Wang S. Cardiovascular modulating effects of Magnolol and Honokiol, two polyphenolic compounds from traditional Chinese medicine—Magnolia officinalis. Curr Drug Targets. 2020;21(6):559–72. doi:10.2174/1389450120666191024175727. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Yue MF, Zhang C, Wu ZY. Research progress on the structure and function of AP2/ERF family proteins in plant transcription factors. Biotechnol Bull. 2022;38(12):11–26. (In Chinese). doi:10.13560/j.cnki.biotech.bull.1985.2022-0432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang JY, Wang QJ, Guo ZR. Research progress of AP2/ERF transcription factors in plants. Hereditas. 2012;34(7):44–56. (In Chinese). doi:10.3724/SP.J.1005.2012.00835. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Zhang Y, Huang S, Wang X, Liu J, Guo X, Mu J, et al. Defective APETALA2 genes lead to sepal modification in Brassica crops. Front Plant Sci. 2018;20(9):367. doi:10.3389/fpls.2018.00367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang Z, Zhang H, Quan R, Wang XC, Huang R. Transcriptional regulation of the ethylene response factor LeERF2 in the expression of ethylene biosynthesis genes controls ethylene production in tomato and tobacco. Plant Physiol. 2009;150(1):365–77. doi:10.1104/pp.109.135830. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Gu C, Guo ZH, Hao PP, Wang GM, Jin ZM, Zhang SL. Multiple regulatory roles of AP2/ERF transcription factor in angiosperm. Bot Stud. 2017;58(1):6. doi:10.1186/s40529-016-0159-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Feng K, Hou XL, Xing GM, Liu JX, Duan AQ, Xu ZS, et al. Advances in AP2/ERF super-family transcription factors in plant. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2020;40(6):750–76. doi:10.1080/07388551.2020.1768509. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Xie Z, Nolan TM, Jiang H, Yin Y. AP2/ERF transcription factor regulatory networks in hormone and abiotic stress responses in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:228. doi:10.3389/fpls.2019.00228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Xie W, Ding C, Hu H, Dong G, Zhang G, Qian Q, et al. Molecular events of rice AP2/ERF transcription factors. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(19):12013. doi:10.3390/ijms231912013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Pan Q, Wang C, Xiong Z, Wang H, Fu X, Shen Q, et al. CrERF5 an AP2/ERF transcription factor, positively regulates the biosynthesis of bisindole alkaloids and their precursors in Catharanthus roseus. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:931. doi:10.3389/fpls.2019.00931. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Zhao C, Liu X, Gong Q, Cao J, Shen W, Yin X, et al. Three AP2/ERF family members modulate flavonoid synthesis by regulating type IV chalcone isomerase in citrus. Plant Biotechnol J. 2021;19(4):671–88. doi:10.1111/pbi.13494. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Chuck G, Meeley R, Hake S. Floral meristem initiation and meristem cell fate are regulated by the maize AP2 genes ids1 and sid1. Development. 2008;135(18):3013–9. doi:10.1242/dev.024273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Chen K, Tang W, Zhou Y, Chen J, Xu Z, Ma R, et al. AP2/ERF transcription factor GmDREB1 confers drought tolerance in transgenic soybean by interacting with GmERFs. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2022;170:287–95. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.12.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Lv B, Deng H, Wei J, Feng Q, Liu B, Zuo A, et al. SmJAZs-SmbHLH37/SmERF73-SmSAP4 module mediates jasmonic acid signaling to balance biosynthesis of medicinal metabolites and salt tolerance in Salvia miltiorrhiza. New Phytol. 2024;244(4):1450–66. doi:10.1111/nph.20110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zheng H, Jing L, Jiang X, Pu C, Zhao S, Yang J, et al. The ERF-VII transcription factor SmERF73 coordinately regulates tanshinone biosynthesis in response to stress elicitors in Salvia miltiorrhiza. New Phytol. 2021;231(5):1940–55. doi:10.1111/nph.17463. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Pei M, Yang P, Li J, Wang Y, Li J, Xu H, et al. Comprehensive analysis of pepper (Capsicum annuum) RAV genes family and functional identification of CaRAV1 under chilling stress. BMC Genom. 2024;25(1):731. doi:10.1186/s12864-024-10639-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Yan X, Huang W, Liu C, Hao X, Gao C, Deng M, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the AP2/ERF transcription factor gene family in hybrid tea rose under drought stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(23):12849. doi:10.3390/ijms252312849. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Zhang M, Lu P, Zheng Y, Huang X, Liu J, Yan H, et al. Genome-wide identification of AP2/ERF gene family in Coptis chinensis Franch reveals its role in tissue-specific accumulation of benzylisoquinoline alkaloids. BMC Genom. 2024;25(1):972. doi:10.1186/s12864-024-10883-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Wei Y, Kong Y, Li H, Yao A, Han J, Zhang W, et al. Genome-wide characterization and expression profiling of the AP2/ERF gene family in Fragaria vesca L. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(14):7614. doi:10.3390/ijms25147614. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Xu Y, Li X, Yang X, Wassie M, Shi H. Genome-wide identification and molecular characterization of the AP2/ERF superfamily members in sand pear (Pyrus pyrifolia). BMC Genom. 2023;24(1):32. doi:10.1186/s12864-022-09104-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Hu F, Zhang Y, Guo J. Identification and Characterization of AP2/ERF transcription factors in Yellow Horn. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(23):14991. doi:10.3390/ijms232314991. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Qian Z, Rao X, Zhang R, Gu S, Shen Q, Wu H, et al. Genome-wide identification, evolution, and expression analyses of AP2/ERF family transcription factors in Erianthus fulvus. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(8):7102. doi:10.3390/ijms24087102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Zhao M, Li Y, Zhang X, You X, Yu H, Guo R, et al. Genome-wide identification of AP2/ERF superfamily genes in Juglans mandshurica and expression analysis under cold stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(23):15225. doi:10.3390/ijms232315225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Zha LP, Yuan Y, Huang LQ, Yu SL. Identification and bioinformatics analysis of genes associated with MVA pathway in Magnolia officinalis. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2015;40(11):2077–83. (In Chinese). doi:10.4268/cjcmm20151104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zhang BN, Zhao MH, Tian H, Zhang YY, Wang Q, Wang T, et al. Mining and bioinformatics analysis of the Dirigent gene family in Magnolia officinalis. Chin J Tradit Chin Med. 2024;42(1):189–93. (In Chinese). doi:10.13193/j.issn.1673-7717.2024.01.034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Shigyo M, Hasebe M, Ito M. Molecular evolution of the AP2 subfamily. Gene. 2006;366(2):256–65. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2005.08.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Sakuma Y, Liu Q, Dubouzet JG, Abe H, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. DNA-binding specificity of the ERF/AP2 domain of Arabidopsis DREBs, transcription factors involved in dehydration- and cold-inducible gene expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;290(3):998–1009. doi:10.1006/bbrc.2001.6299. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Zhang Y, Xia P. The DREB transcription factor, a biomacromolecule, responds to abiotic stress by regulating the expression of stress-related genes. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;243:125231. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Chen C, Li Y, Zhang H, Ma Q, Wei Z, Chen J, et al. Genome-wide analysis of the RAV transcription factor genes in rice reveals their response patterns to hormones and virus infection. Viruses. 2021;13(5):752. doi:10.3390/v13050752. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Zha Q, Yin X, Xi X, Jiang A. Heterologous VvDREB2c expression improves heat tolerance in Arabidopsis by inducing photoprotective responses. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(6):5989. doi:10.3390/ijms24065989. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Li Q, Zhang L, Chen P, Wu C, Zhang H, Yuan J, et al. Genome-wide identification of APETALA2/ETHYLENE RESPONSIVE FACTOR transcription factors in cucurbita moschata and their involvement in ethylene response. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:847754. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.847754. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Wang J, Lei HL, Liu XJ, Cai Y. Bioinformatics identification of AP2/ERF gene family in medicinal plant Arnebia euchroma. Xinjiang Med J. 2024;54(8):920–30. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

40. Ma X, Zhu P, Du Y, Song Q, Ye W, Tang X, et al. Transcriptome analysis and genome-wide identification of the dehydration-responsive element binding gene family in jackfruit under cold stress. BMC Genom. 2024;25(1):833. doi:10.1186/s12864-024-10732-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Sheng S, Guo X, Wu C, Xiang Y, Duan S, Yang W, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of DREB genes in alfalfa (Medicago sativa) in response to cold stress. Plant Signal Behav. 2022;17(1):2081420. doi:10.1080/15592324.2022.2081420. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Wu K, Duan X, Zhu Z, Sang Z, Duan J, Jia Z, et al. Physiological and transcriptome analysis of Magnolia denudata leaf buds during long-term cold acclimation. BMC Plant Biol. 2021;21(1):460. doi:10.1186/s12870-021-03181-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Deng S, Ma J, Zhang L, Chen F, Sang Z, Jia Z, et al. De novo transcriptome sequencing and gene expression profiling of Magnolia wufengensis in response to cold stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19(1):321. doi:10.1186/s12870-019-1933-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Huang QH, Tian BW, Hua X, Zhou XD, Jiang ZH, Chen YH, et al. Research progress on the response of AP2/ERF transcription factor family to abiotic stress in woody plants. J Nantong Univ Nat Sci Ed. 2025;24(1):74–84. (In Chinese). doi:10.11983/CBB19243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Jofuku KD, Omidyar PK, Gee Z, Okamuro JK. Control of seed mass and seed yield by the floral homeotic gene APETALA2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(8):3117–22. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409893102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Fan L, Chen M, Dong B, Wang N, Yu Q, Wang X, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of flower bud differentiation in Magnolia sinostellata. Genes. 2018;9(4):212. doi:10.3390/genes9040212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Ohme-Takagi M, Shinshi H. Ethylene-inducible DNA binding proteins that interact with an ethylene-responsive element. Plant Cell. 1995;7(2):173–82. doi:10.1105/tpc.7.2.173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Gui J, Lam PY, Tobimatsu Y, Sun J, Huang C, Cao S, et al. Fibre-specific regulation of lignin biosynthesis improves biomass quality in Populus. New Phytol. 2020;226(4):1074–87. doi:10.1111/nph.16411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Su ZL, Li AM, Wang M, Qin CX, Pan YQ, Liao F, et al. The role of AP2/ERF transcription factors in plant responses to biotic stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(10):4921. doi:10.3390/ijms26104921. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Wang L, Zhao H, Li R, Tian R, Jia K, Gong Y, et al. Unveiling the evolutionary and transcriptional landscape of ERF transcription factors in wheat genomes: a genome-wide comparative analysis. BMC Genom. 2025;26(1):503. doi:10.1186/s12864-025-11671-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Xu S, Yao S, Huang R, Tan Y, Huang D. Transcriptome-wide analysis of the AP2/ERF transcription factor gene family involved in the regulation of gypenoside biosynthesis in Gynostemma pentaphyllum. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2020;154:238–47. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.05.040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools