Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Beyond Photomorphogenesis: Multifaceted Roles of BBX Transcription Factors in Plant Stress Responses and Breeding Perspectives

Key Laboratory of Plant Functional Genomics of the Ministry of Education, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, 225009, China

* Corresponding Author: Chen Lin. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant Responses and Adaptations to Environmental Stresses)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(11), 3349-3370. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.071525

Received 06 August 2025; Accepted 21 October 2025; Issue published 01 December 2025

Abstract

Extensive transcriptomic reprogramming is triggered by biotic and abiotic stresses in plants, with coordinated regulation mediated through multiple transcription factor families, such as WRKY, MYB, NAC, and BBX proteins. Among these, B-box (BBX) proteins represent a distinct class of zinc finger transcription factors characterized by the presence of conserved B-box domains. They serve as central regulators in plant photomorphogenesis and developmental processes. Accumulating genetic and biochemical evidence demonstrates that BBX family members orchestrate plant responses to biotic and abiotic stresses through multifaceted molecular mechanisms, including the regulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis, enhancement of anthocyanin biosynthesis, and modulation of hormonal signaling pathways. This review systematically summarizes recent advances in the identification of BBX family genes in different plant species. Furthermore, their emerging roles in mediating plant stress responses are elucidated, with molecular mechanisms being comprehensively analyzed at both transcriptional and post-translational levels. However, to fully harness the potential of BBX genes in crop improvement, a deeper understanding of their functional mechanisms including BBX-mediated hormonal crosstalk networks, growth–defense trade-offs, and more extensive field performance data remains essential. These insights provide a theoretical foundation for developing climate-resilient crop varieties through targeted genetic improvement strategies.Keywords

B-box (BBX) proteins represent an evolutionarily conserved family of zinc finger transcription factors that are widely distributed across eukaryotic organisms. These proteins are defined by the presence of one or more characteristic B-box domains, which are zinc-binding motifs that mediate protein-protein interactions and play crucial roles in transcriptional regulation. Comparative genomic analyses have revealed remarkable structural diversification between plant and animal BBX proteins, suggesting distinct evolutionary trajectories and functional specialization in different kingdoms [1]. In animals, the B-box domain combines with RING-finger and coiled-coil domains to assemble tripartite motif (TRIM) proteins, a class of E3 ubiquitin ligases that orchestrate ubiquitin-mediated protein modification. These multifunctional regulators are indispensable in core biological mechanisms such as cell proliferation, apoptosis, DNA repair, transcriptional regulation, and immune signaling [2]. In plants, BBX proteins act as transcription factors that are characterized by the presence of zinc-finger B-box domains located at their N-terminal regions [3]. Functional studies have revealed that different BBX members participate in processes such as shade avoidance, photomorphogenesis, and vegetative-to-reproductive phase transition through modulation of light-responsive signaling cascades, thereby fulfilling essential regulatory functions during plant growth and development [1,4,5]. Recent transcriptomic analyses indicate that the expression of some BBX genes is strongly induced by different phytohormones such as abscisic acid (ABA), gibberellic acid (GA), and jasmonic acid (JA), suggesting their potential roles in hormonal signal transduction pathways [5]. While several transcription factor families, such as WRKY, MYB, and NAC, are well-established central regulators in plant stress response [6–8], BBX proteins stand out due to their unique dual functionality as core components of light signaling and integrators of multiple stress-adaptive pathways. This distinctive capacity to directly couple photoperception with downstream stress acclimation mechanisms differentiates BBX factors from other TF families and underscores their emerging significance in plant environmental adaptation. The functions of BBX proteins have been systematically characterized in photomorphogenesis and developmental regulation, whereas recent studies have not only elucidated these established roles but also identified functions of BBX family members in mediating plant responses to diverse biotic and abiotic stresses, uncovering previously unknown BBX-associated regulatory networks. This review comprehensively evaluates current understanding of the multifaceted roles of BBX genes in stress response mechanisms. In addition, the potential application of BBX genes in agriculture is discussed, which offers promising strategies for engineering climate-resilient crops.

2 Overview of the BBX Gene Family

2.1 Structural Diversity and Evolutionary Dynamics of the BBX Protein Family in Plants

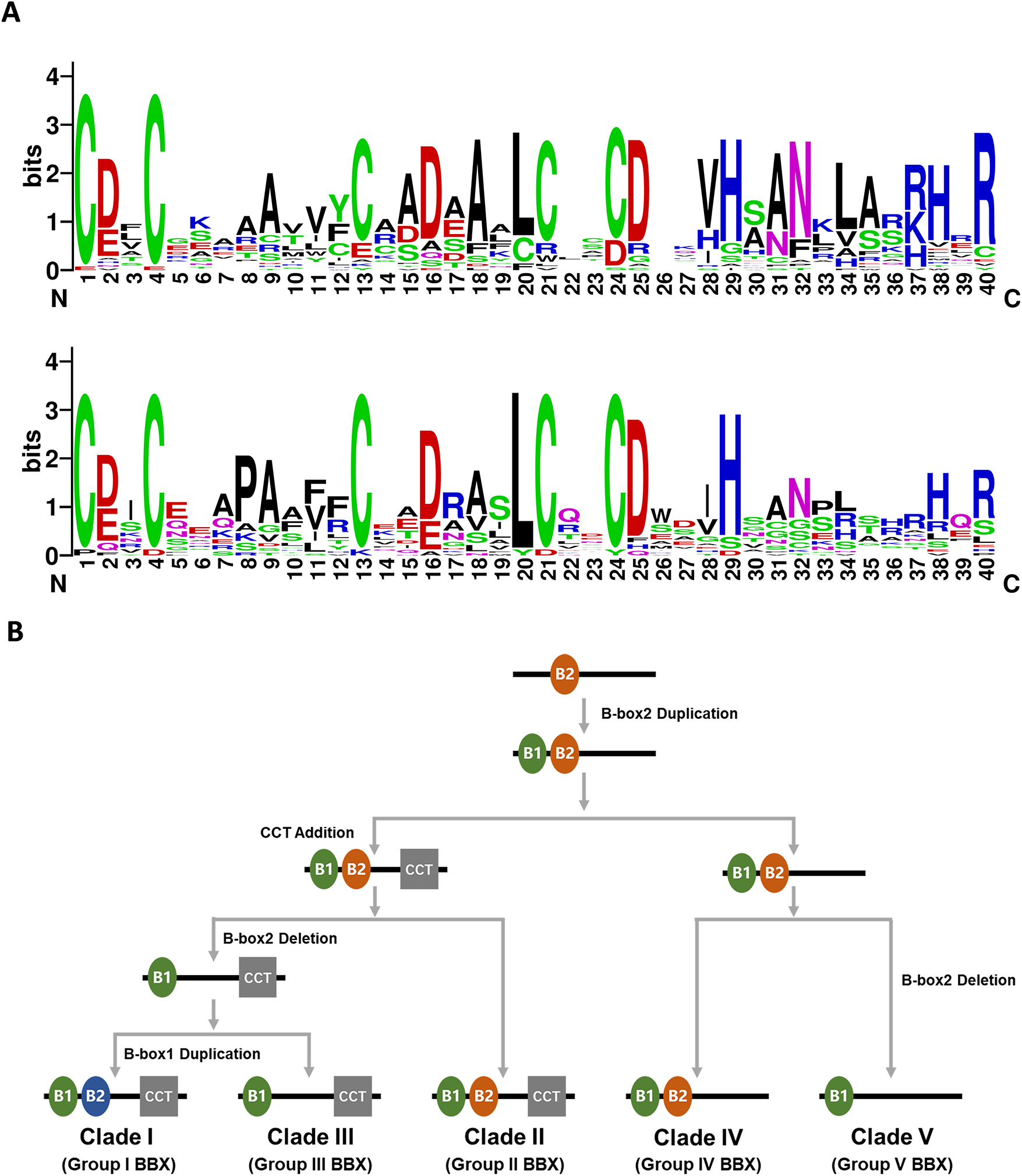

The defining feature of BBX proteins is the presence of one or two B-box zinc-finger domains, each comprising approximately 40 amino acid residues that ligate two zinc ions (Fig. 1A), some members additionally possess a C-terminal CCT (CO, COL, TOC1) domain [3]. The first BBX protein identified in plants was CONSTANS (CO) in Arabidopsis thaliana [9,10]. Subsequently, other members were identified and designated as CONSTANS-like (COL) proteins [11]. Further characterization revealed seven Arabidopsis proteins containing one or two B-box zinc finger domains but lacking the C-terminal CCT domain. These proteins were systematically renamed AtBBX1 to AtBBX32 [3].

Figure 1: Conserved domain alignment and evolutionary divergence analysis of BBX protein family in plants. (A) The amino acid sequence alignment of the B-box 1 (up) and B-box 2 (down) of the AtBBXs in Arabidopsis thaliana, generated by WEBLOGO (https://weblogo.berkeley.edu/logo.cgi, accessed on 02 August 2025); (B) The schematic represents the conserved domain architecture (B-box 1 (B1), B-box 2 (B2), and CCT domains) and phylogenetic divergence of BBX proteins throughout the plant kingdom. Key evolutionary transitions underlying functional diversification of this transcription factor family are indicated (Adapted from [12])

Comparative phylogenetic analyses of BBX gene families in diverse plant species show that BBX proteins maintain evolutionarily conserved clustering patterns. It was proposed that during the expansion of the BBX protein family in plants, two duplication events and two deletion events of the B-box domains led to the emergence of five distinct structural groups [12] (Fig. 1B). Based on this evolutionary model, ancestral plant BBX proteins possessed only one B-box domain that later experienced duplication during genome evolution. An evolutionary deletion in ancestral clade IV BBX proteins gave rise to the single B-box structure that defines clade V. Subsequent acquisition of a C-terminal CCT domain produced the two B-box, CCT-containing architecture characteristic of early clade II members. Within this clade, loss of B-box 2 in certain lineages led to the emergence of clade III proteins, which retain only one B-box domain alongside the CCT module. Finally, duplication of B-box 1 in an early clade II protein likely generated the distinctive two B-box/one CCT configuration that typifies clade I [12]. This hypothesis is supported by existing evidence, particularly the prevalence of BBX proteins with a single B-box domain in most green algal species (e.g., Chlamydomonas reinhardtii) [13].

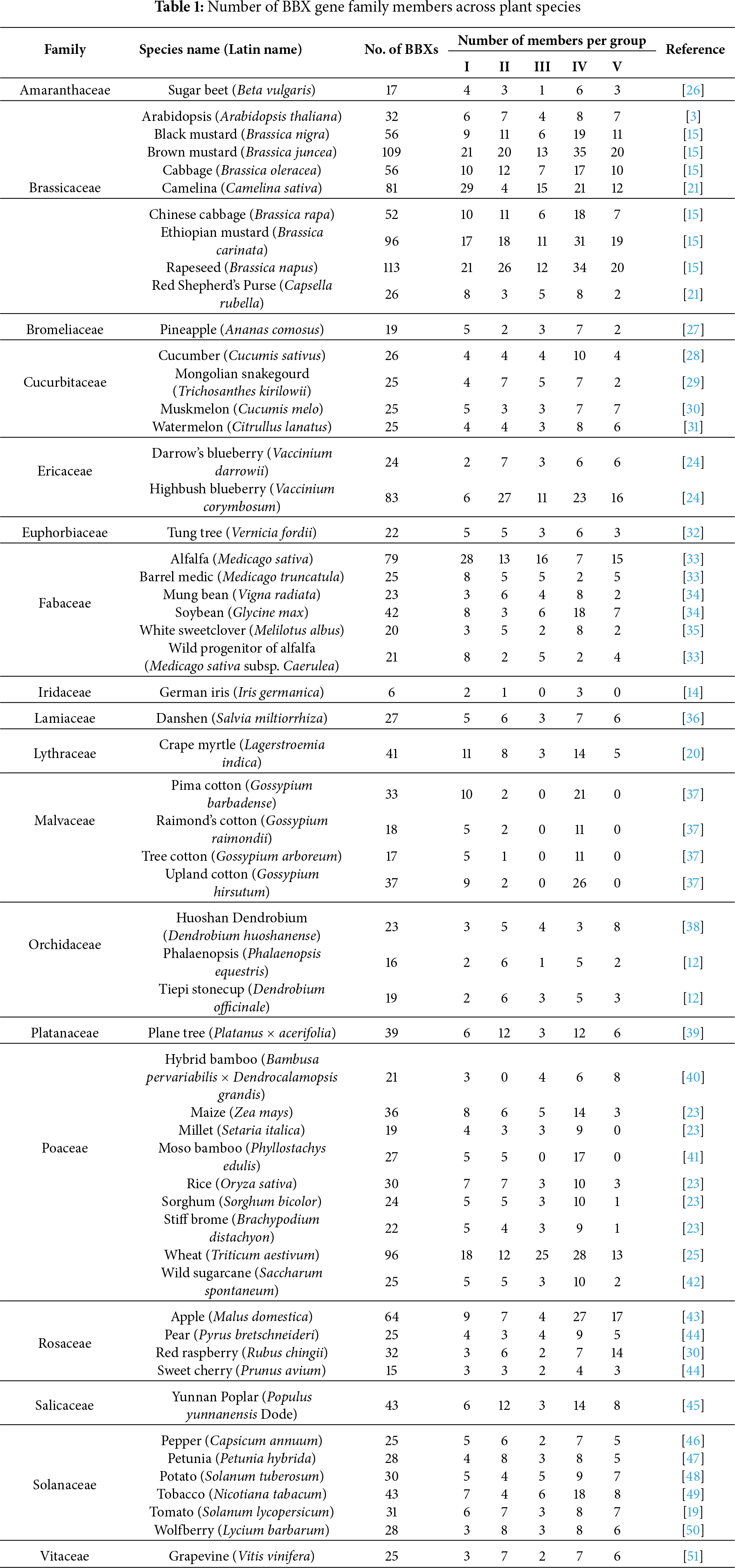

Genome-wide analyses have revealed BBX gene family members across multiple plant species in recent years (Table 1), with their numbers ranging from 6 in Iris germanica [14] to 113 in Brassica napus [15]. Proteins containing both B-box and CCT domains are classified as COL genes [16,17], while those possessing two B-box domains but lacking a CCT domain are categorized into the Double B-box (DBB) protein family [18].

The expansion of the BBX gene family occurs primarily through whole-genome duplication or segmental duplication. For instance, 70.73% (29/41) and 41.40% (12/29) of BBX genes in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) and Crape myrtle (Lagerstroemia indica), respectively, arise from segmental duplication [19,20]. In polyploid species, the number of BBX genes exhibits substantial expansion following chromosome doubling events, as demonstrated in polyploid crops of the Brassicaceae [21] and Poaceae [22,23]. Group IV contains the largest number of members across most plant species, implying its potential core functional roles, particularly in light signaling pathways. Group II members display pronounced expansion in Brassicaceae and Vaccinium spp., likely indicative of functional diversification [21,24]. In contrast, Group V members are either absent or occur in minimal numbers in Gossypium species and certain Poaceae plants. Notably, they are absent in foxtail millet (Setaria italica) and moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis), represented by only one single copy in Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) and Stiff brome (Brachypodium distachyon), and restricted to three copies in maize (Zea mays) and rice (Oryza sativa). This distribution pattern suggests functional specialization of this subgroup within specific lineages [23,25].

2.2 The BBX-Mediated Transcriptional Regulatory Network

In light signaling responses, key regulatory proteins such as PHYs, CRYs, COP1, ELF3, PIF3/4, HY5, and Flowering Locus T (FT) precisely control BBX protein activity through transcriptional regulation or post-translational modulation. These well-characterized regulatory modules mediate critical physiological processes including photoperiodic responses, flowering time regulation, photomorphogenesis, and shade avoidance [52,53]. Notably, emerging evidence suggests these light signaling components may also integrate with BBX-mediated defense mechanisms. Furthermore, selective protein turnover mediated by E3 ubiquitin ligases provides an additional layer of regulation by targeting BBX proteins for degradation, thereby fine-tuning their physiological functions. In Arabidopsis, AtCOP1 promotes the ubiquitination-dependent degradation of AtBBX21, AtBBX28 and AtBBX29 [54,55]. In apple (Malus domestica), the MYB30-Interacting E3 Ligase 1 (MdMIEL1) protein ubiquitinates and degrades MdBBX7 and MdBBX37, thereby improving drought and cold tolerance [56]. BBX proteins may also be activated via MAPK-mediated phosphorylation. In tomato, SlBBX17 is phosphorylated by SlMPK1/2 under cold stress, subsequently forming a complex with HY5 to activate the expression of C-repeat Binding Factors (SlCBFs), thereby conferring enhanced cold tolerance [57]. In rice, OsMPK1 phosphorylates OsBBX17 under saline-alkaline stress, which alleviates its transcriptional repression of downstream targets and enhances Na+/K+ homeostasis [58]. Furthermore, BBX proteins contribute to plant stress tolerance by modulating both JA [56] and ABA signaling pathways [59–61].

BBX proteins function as transcriptional regulators by directly binding to cis-acting regulatory elements such as T-box and G-box motifs at the promoter regions, thereby activating downstream gene expression [55,62]. Analysis of BBX gene promoters across multiple species reveals a conserved enrichment of light-responsive elements (e.g., TCT-motif, Box4, G-box) and phytohormone-responsive motifs (e.g., CGTCA-motif, P-box, TGA-element), supporting their central governing roles in photoperiodism, photomorphogenesis, and vegetative-to-reproductive transition [16,35]. Furthermore, multiple BBX gene promoters contain stress-responsive motifs (e.g., CCAAT-box, ARE), suggesting their potential involvement in both abiotic and biotic stress response mechanisms [43]. Transcriptional profiling demonstrates that the expression of BBX members responds to light, hormones, and diverse stress conditions [31,40]. In blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum), red and blue light treatments induce upregulation of VcBBX15a1-a4 and VcBBX7a1-a4, while suppressing VcBBX9b3, VcBBX30a2, and VcBBX30a3 [24]. In tung tree (Vernicia fordii), shading treatment significantly alters the expression patterns of VfBBX4, VfBBX5, VfBBX9, VfBBX12, VfBBX13, and VfBBX22 [32]. Among 12 analyzed MdBBX genes in apple, six exhibit pronounced upregulation under osmotic stress, salinity, cold, and exogenous ABA treatment [43]. Similarly, the transcript levels of NtBBX12, NtBBX13, NtBBX16, and NtBBX17 show significant responsiveness to salt stress, drought, cold stress and Ralstonia solanacearum infection in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) [49].

BBX family members display marked spatiotemporal heterogeneity in their expression profiles. The transcript abundance of multiple members exhibits considerable variation across distinct tissues or at different developmental stages within the same tissue. In cucumber (Cucumis sativus), CsCOL9 exhibits distinct spatiotemporal expression patterns across various tissues (roots, stems, leaves, and fruits) at different developmental stages [59]. Structural analysis of the AtBBX1 protein reveals its formation of a head-to-tail oligomeric configuration through B-box domains. This oligomeric complex specifically recognizes and binds four TGTG motifs in the FT promoter through multiple CCT domains, consequently activating FT expression [63]. This study yields significant insights into COL member functionality. Subcellular localization studies confirm that BBX proteins, as canonical transcription factors, are nuclear-localized [17,29].

3 Functional Mechanisms of the BBX Gene Family in Abiotic and Biotic Stress Responses

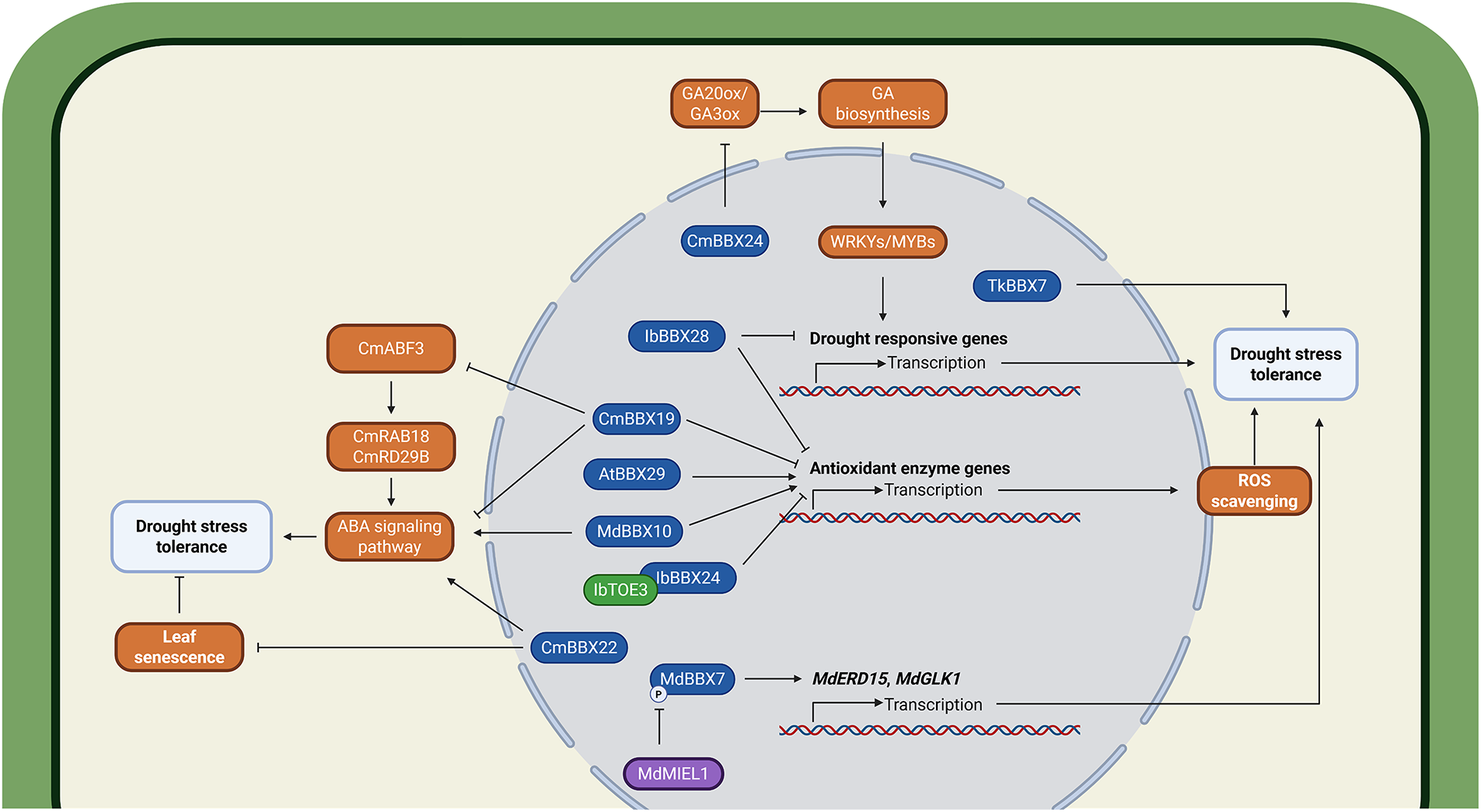

3.1 Molecular Regulation of Drought Stress

BBX transcription factors coordinate plant drought responses through synergistic regulatory networks (Fig. 2). In sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas), IbBBX24 directly binds the G-box motif (CACGTG) at the promoter region of IbPRX17, activating the expression of IbPRX17 to enhance reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging and confer tolerance to salt and drought stress. The Target of Early Activation Tagged (TOE) protein IbTOE3 facilitates this process by serving as a molecular bridge that enhances the DNA-binding ability of IbBBX24 [64]. Although drought stress induces the expression of IbBBX28 in sweet potato, transgenic Arabidopsis overexpressing IbBBX28 show reduced drought tolerance due to decreased antioxidant enzyme (Superoxide Dismutase (SOD), Peroxidase (POD), Catalase (CAT)) activities and downregulated stress-responsive genes [65]. Consistent with these findings, genetic silencing of AhBBX6 in peanut (Arachis hypogaea) likewise disrupts salt and drought tolerance by attenuating the enzymatic activities of SOD, POD and CAT [66].

Figure 2: BBX transcription factors orchestrate drought-responsive gene networks through integrated phytohormone and other signaling pathways. BBX proteins differentially regulate drought stress responses through distinct molecular mechanisms, including modulation of gibberellin (GA) biosynthesis, abscisic acid (ABA) signaling pathways, reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis, and leaf senescence. CmBBX24 enhances drought tolerance by upregulating GA20ox and GA3ox genes to activate the gibberellin (GA) biosynthesis pathway, which subsequently promotes the expression of drought-responsive genes such as WRKY and MYB. In contrast, IbBBX28 negatively regulates drought tolerance by suppressing the expression of drought-responsive genes and ROS-scavenging genes. CmBBX19 reduces drought tolerance by inhibiting ROS-scavenging genes, thereby decreasing the rate of ROS clearance. Similarly, IbTOE3 interacts with IbBBX24, and together they suppress ROS-scavenging genes, further reducing drought tolerance. Additionally, CmBBX19 inhibits the ABA signaling pathway, further compromising drought tolerance. AtBBX29 and MdBBX10 improve drought tolerance by activating the expression of ROS-scavenging genes, enhancing ROS clearance efficiency. MdBBX10 also further enhances drought tolerance by activating the ABA signaling process. CmBBX22 improves drought resistance by activating the ABA signaling pathway and simultaneously inhibiting leaf senescence. MdBBX7 enhances drought tolerance by activating MdERF15 and MdGLK1, whereas MdMIEL1 can phosphorylate MdBBX7, reducing its activity. TkBBX7 improves drought tolerance, though its mechanism remains unclear. The protein prefixes denote the following species: Cm, Cucumis melo; Ib, Ipomoea batatas; At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Md, Malus domestica; Tk, Trichosanthes kirilowii. The schematic model was created in BioRender. Lin, C. (2025) https://BioRender.com/l33w68p (accessed on 03 August 2025)

The Group IV BBX member CpBBX19 from wintersweet (Chimonanthus praecox) shows significant upregulation in response to high temperature, low temperature, NaCl, polyethylene glycol (PEG) treatments, as well as exogenous ABA and MeJA application. Under drought and salt stress, overexpression of CpBBX19 in Arabidopsis displayed markedly reduced electrolyte leakage and malondialdehyde (MDA) accumulation relative to wild-type plants [67]. Similarly, overexpression of AtBBX29 enhances drought tolerance in sugarcane (Saccharum spp. hybrid) by maintaining photosynthetic efficiency and boosting antioxidant and osmolyte capacity [68]. In apple, MdBBX7 is regulated through ubiquitination and degradation mediated by the E3 ubiquitin ligase MdMIEL1. Under drought stress, reduced MdMIEL1 abundance leads to elevated MdBBX7 protein levels, which subsequently transactivates downstream drought-responsive genes, including Early Responsive to Dehydration 15 (MdERD15), Golden2-like 1 (MdGLK1), and Ethylene Response Factor 1 (MdERF1), thereby enhancing drought tolerance [69]. In contrast to typical positive regulators, CmBBX19 in chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum morifolium) negatively modulates drought tolerance. CmBBX19 directly interacts with CmABF3, a central ABA signaling component, and represses the transcriptional activation of downstream ABA-responsive genes, including Responsive to ABA 18 (CmRAB18), Responsive to Desiccation 29B (CmRD29B), CmPOD2, and Cellulose synthase-like protein G2 (CmCSLG2) [70]. In contrast, heterologous expression of CmBBX22 in Arabidopsis suppresses key senescence-associated genes including Senescence-Associated Gene 29 (SAG29), NONYELLOWING 1/2 (NYE1/2), and Nonyellow Coloring 1 (NYC1), while activating ABI3 and ABI5 expression, consequently delaying both stress-induced chlorophyll degradation and leaf senescence to confer enhanced drought tolerance [71]. Furthermore, CmBBX24 in chrysanthemum delays flowering and enhances abiotic stress tolerance by suppressing GA biosynthesis genes (GA20ox and GA3ox) leading to reduced GA levels under long-day conditions, while simultaneously activating WRKY/MYB transcriptional networks to enhance resilience to freezing and drought stress [72].

In addition to mediating drought tolerance via physiological and biochemical acclimation, BBX proteins may also orchestrate adaptive drought escape responses by accelerating flowering time [73]. The sensitivity of BBX genes to stress-related phytohormones (e.g., ABA, SA, and JA), coupled with their regulatory roles in the vegetative-to-reproductive transition, suggests their involvement in this adaptive mechanism.

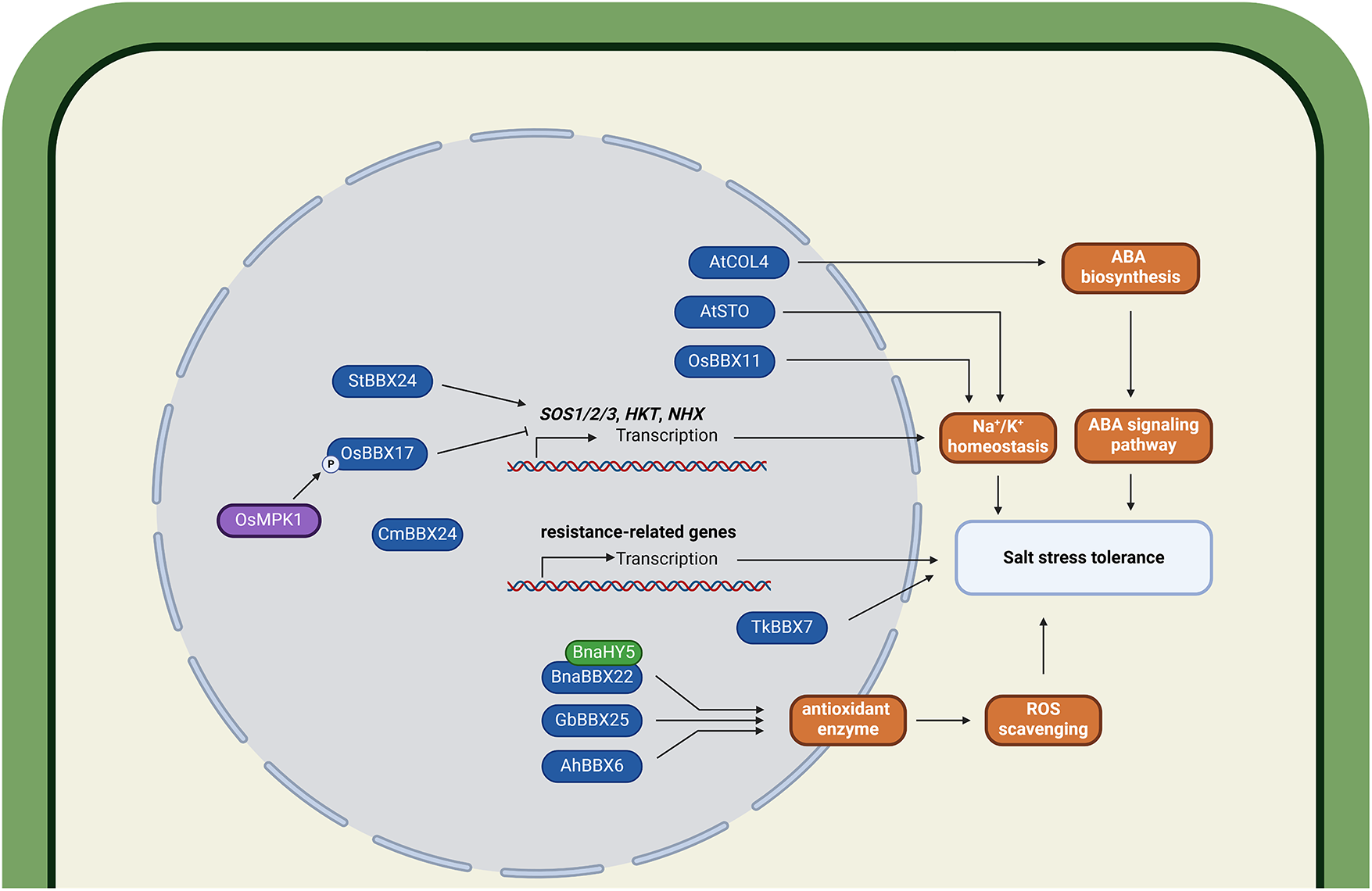

3.2 Salt Stress Adaptation Mechanisms

The previous functional characterization of BBX family members in Arabidopsis showed that heterologous expression of AtBBX24 (also designated as Salt Tolerance (STO)) confers enhanced salt tolerance in yeast calcineurin mutants [74]. Subsequent studies have consistently demonstrated that BBX genes are responsive to salt stress and stress-related hormone signaling in various plant species [29,66]. During salt stress, BBX proteins predominantly improve salinity tolerance through modulation of ROS scavenging enzyme activity, Na+/K+ homeostasis maintenance, and ABA signaling pathways (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Regulatory roles of BBX proteins in plant adaptation to salinity stress. BBX proteins confer tolerance to salinity stress in plants mainly through coordinated regulation of sodium-potassium (Na+/K+) homeostasis, abscisic acid (ABA) signaling, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging. AtCOL4 enhances salt stress tolerance by activating the ABA biosynthesis and signaling pathways. AtSTO, OsBBX11, StBBX24, and OsBBX17 improve salt tolerance by maintaining Na+/K+ homeostasis. Among them, StBBX24 and OsBBX17 function by activating the expression of genes such as SOS1/2/3, HKT, and NHX. CmBBX24 increases salt tolerance by activating resistance-related genes. BnaBBX22, GbBBX25, and AhBBX6 enhance salt tolerance by boosting antioxidant enzyme activity, thereby increasing the ROS scavenging rate. Specifically, BnaBBX22 functions through its interaction with BnaHY5. TkBBX7 improves salt tolerance through an unknown mechanism. The protein prefixes denote the following species: At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Os, Oryza sativa; St, Solanum tuberosum; Cm, Chrysanthemum morifolium; Gb, Ginkgo biloba; Ah, Arachis hypogaea; Tk, Trichosanthes kirilowii. The schematic model was created in BioRender. Lin, C. (2025) https://BioRender.com/l33w68p (accessed on 03 August 2025)

BnBBX22.A07 from B. napus enhances salt tolerance in both Arabidopsis and B. napus by activating ROS scavenging genes and reducing salt-induced accumulation of superoxide anions and hydrogen peroxide. BnBBX22.A07 forms a complex with BnHY5.C09, which amplifies BnHY5.C09-mediated transactivation of BnWRKY33, thereby upregulating salt-tolerance genes [75]. Under non-stressed conditions, the rice OsBBX17 protein suppresses transcription of High-Affinity K+ Transporters 2/7 (OsHAK2/7) by directly binding to G-box cis-elements in their promoters, thereby maintaining Na+/K+ homeostasis. However, under saline-alkaline stress conditions, activation of the OsMPK1-mediated MAPK signaling cascade induces OsMPK1-dependent phosphorylation of OsBBX17, which significantly attenuates its DNA-binding capacity. This post-translational modification consequently relieves OsBBX17-mediated transcriptional suppression of OsHAK2/7, ultimately conferring enhanced salinity tolerance [58]. Another study identified OsBBX11 within the qSTS4 locus via quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping, demonstrating its role in modulating Na+/K+ homeostasis in roots and shoots under salt stress [76].

Consistent with these findings, overexpression of StBBX24 in potato (Solanum tuberosum) significantly increases POD and SOD enzyme activities in leaves under salt stress while positively regulating salinity tolerance through inducing the expression of SOS1, SOS2, SOS3, HKT, and NHX, thereby influencing Na+ homeostasis [77]. GbBBX25 from ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba L.) encodes a Group IV BBX protein with two B-box domains but lacking a CCT domain. Heterologous expression of GbBBX25 in Populus davidiana × Populus bolleana resulted in transgenic poplar exhibiting elevated soluble sugar levels and enhanced POD activity under salt stress compared to wild-type plants, demonstrating the role of GbBBX25 in promoting salt acclimation [78]. Overexpression of MdBBX10 from apple significantly enhanced tolerance to salt and osmotic stress in Arabidopsis by upregulating the transcript levels of ABA-related and ROS-scavenging genes [79]. AtCOL4 (also designated as AtBBX5) modulates salt tolerance through ABA or salinity signal transduction, though its precise molecular mechanism remains to be elucidated [60].

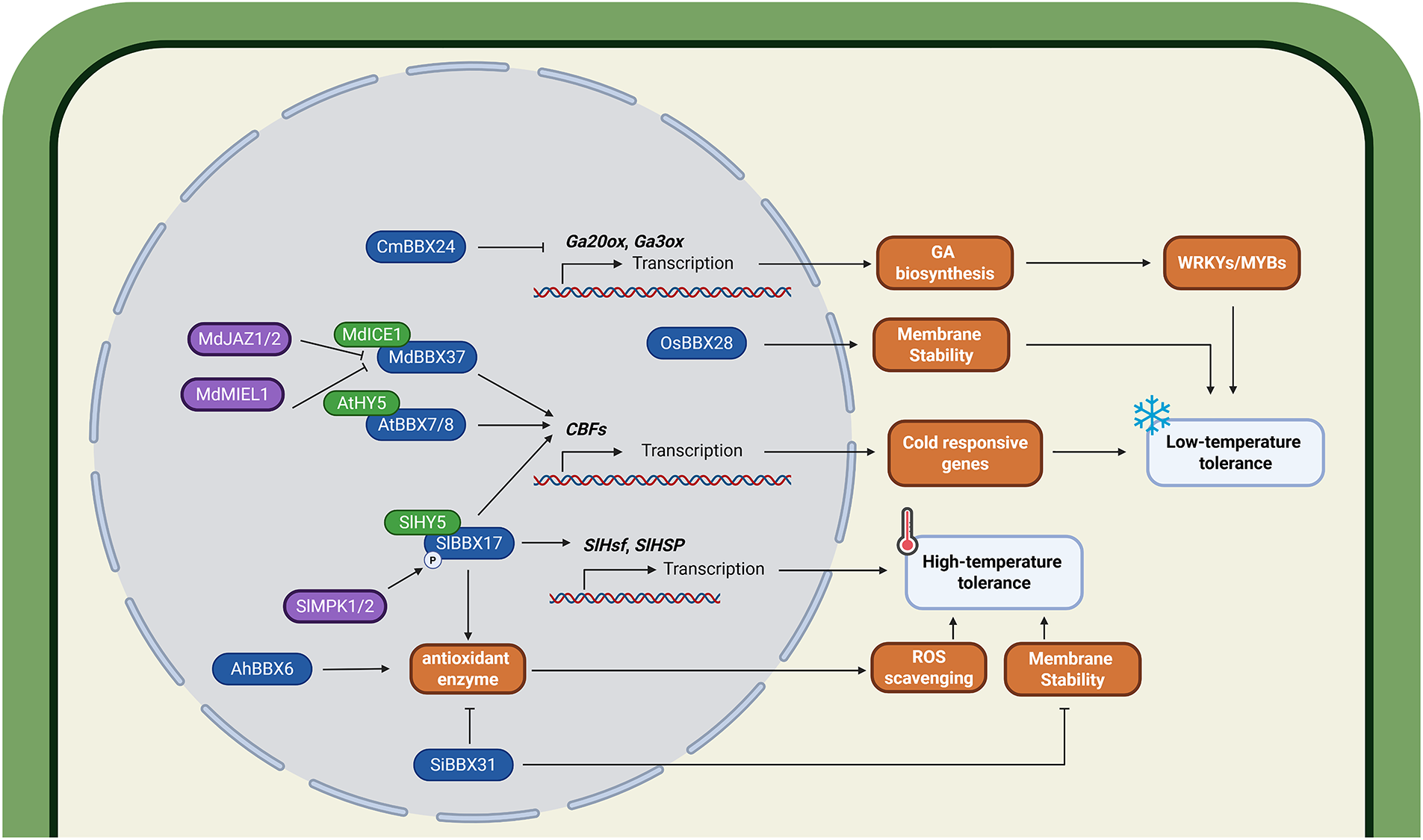

3.3 Temperature Stress Responses

BBX genes are involved in plant response to temperature stress through distinct pathways (Fig. 4). The grape BBX gene VvZFPL is transcriptionally upregulated under cold stress. Overexpression of VvZFPL confers enhanced tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses, including low temperature, salinity, and drought. However, the precise molecular mechanisms underlying this phenomenon remain to be elucidated [80]. In rice, loss-of-function mutants of OsBBX28 exhibit exacerbated plasma membrane damage and significantly compromised freezing tolerance under subzero conditions [81]. In apple, the B-box protein MdBBX37 positively regulates cold tolerance by directly activating transcription of C-repeat Binding Factor 1/4 (MdCBF1/4). Furthermore, MdBBX37 interacts with CBF Expression 1 (MdICE1) to form a protein complex that synergistically enhances the expression of MdCBF1. This regulatory cascade is modulated by JA signaling. Exogenous JA suppresses MdMIEL1, an E3 ubiquitin ligase responsible for MdBBX37 ubiquitination and degradation. Additionally, JA promotes the recognition of Jasmonate-Zim-Domain Protein 1/2 (MdJAZ1/2) by its receptor, leading to their degradation via the 26S proteasome. In the absence of MdJAZ1 and MdJAZ2, MdBBX37 directly upregulates MdCBF1 and MdCBF4 expression. Furthermore, MdBBX37 forms a functional complex with MdICE1 that synergistically enhances MdCBF1 promoter activity. Thus, enhanced JA-mediated signaling activates functional MdBBX37, which further promotes adaptation to cold stress [56].

Figure 4: The roles of BBX proteins in low- and high-temperature stress response. BBX proteins regulate plant thermotolerance and cold adaptation through integrated regulation of gibberellic acid (GA) signaling pathways, reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis, and membrane stability modulation. CmBBX24 enhances low-temperature tolerance by upregulating GA20ox and GA3ox genes to activate the GA biosynthesis pathway, thereby promoting the expression of cold-responsive genes such as WRKY and MYB. OsBBX28 improves low-temperature tolerance by enhancing membrane stability. MdBBX37, AtBBX7/8, and SlBBX17 increase low-temperature tolerance by upregulating the expression of CBF genes, which initiates a series of cold-responsive gene expressions. MdBBX37 functions in conjunction with MdICE1, while its transcriptional activity is inhibited through interactions with MdJAZ1/2. Additionally, MdBBX37 undergoes ubiquitination-mediated degradation by MdMIEL1. Both AtBBX7/8 and SlBBX17 function by interacting with HY5. SlBBX17 also improves plant high-temperature tolerance by activating the expression of SlHsf and SlHsp genes and enhancing antioxidant enzyme activity. The activity of SlBBX17 is activated through phosphorylation by SlMPK1/2. Similarly, AhBBX6 enhances high-temperature tolerance by increasing antioxidant enzyme activity. In contrast, SiBBX31 reduces both antioxidant enzyme activity and membrane stability, thereby decreasing plant high-temperature tolerance. The protein prefixes denote the following species: Cm, Chrysanthemum morifolium; Os, Oryza sativa; Md, Malus domestica; At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Sl, Solanum lycopersicum; Ah, Arachis hypogaea; Si, Setaria italica. The schematic model was created in BioRender. Lin, C. (2025) https://BioRender.com/l33w68p (accessed on 03 August 2025)

The functional interplay between the photomorphogenic regulator HY5 and BBX proteins represents a central regulatory hub in cold stress responses. In Arabidopsis, the CRY2–COP1–HY5–BBX7/8 signaling module orchestrates blue light-dependent cold acclimation. Under low-temperature conditions, blue light triggers AtCRY2 phosphorylation, which stabilizes AtHY5 by attenuating its AtCOP1-mediated degradation. AtHY5, in turn, transcriptionally activates AtBBX7 and AtBBX8, thereby reinforcing freezing tolerance via upregulation of CBF-regulated cold-responsive (COR) genes [82]. Similarly, in tomato, cold stress induces SlMPK1/2-mediated phosphorylation and activation of SlBBX17, which subsequently forms a stable heterodimeric complex with SlHY5. This SlBBX17–SlHY5 module amplifies the transcriptional induction of some SlCBF genes, thereby conferring enhanced cold tolerance [57].

Analogous to their functions in salt stress tolerance, BBX proteins mediate thermotolerance through ROS scavenging pathways. In tomato, SlBBX31 knockout lines exhibit improved heat tolerance, manifested by enhanced membrane stability, elevated antioxidant enzyme activities, and diminished ROS accumulation [83]. Under thermal stress conditions, the expression of AtBBX18 in Arabidopsis is markedly upregulated, functioning as a negative regulator of thermotolerance through suppression of heat-responsive genes (Digalactosyldiacylglycerol Synthase 1 (DGD1), Heat Shock Protein 70/101 (Hsp70/101), and Cytosolic Ascorbate Peroxidase 2 (APX2)) and activation of Heat Shock Factor A2 (HsfA2) [84]. In tomato, both exogenous ABA application and elevated temperature (42°C) significantly promote SlBBX17 accumulation, which enhances thermotolerance by elevating SOD and POD activities to scavenge H2O2 and O2−·. In addition, SlBBX17 upregulates heat-shock response genes (SlHsf, SlHsp), albeit with concomitant trade-offs in plant growth and development [85].

Under UV-B treatment, overexpression of AtBBX22 in Arabidopsis significantly enhances the accumulation of ROS scavenging metabolites, including ascorbic acid, proline, sinapinic acid, and caffeic acid, while simultaneously improving UV-B stress tolerance through upregulation of DNA repair genes (UV Repair Defective 1/3, UVR1/3), thereby facilitating DNA damage repair [86].

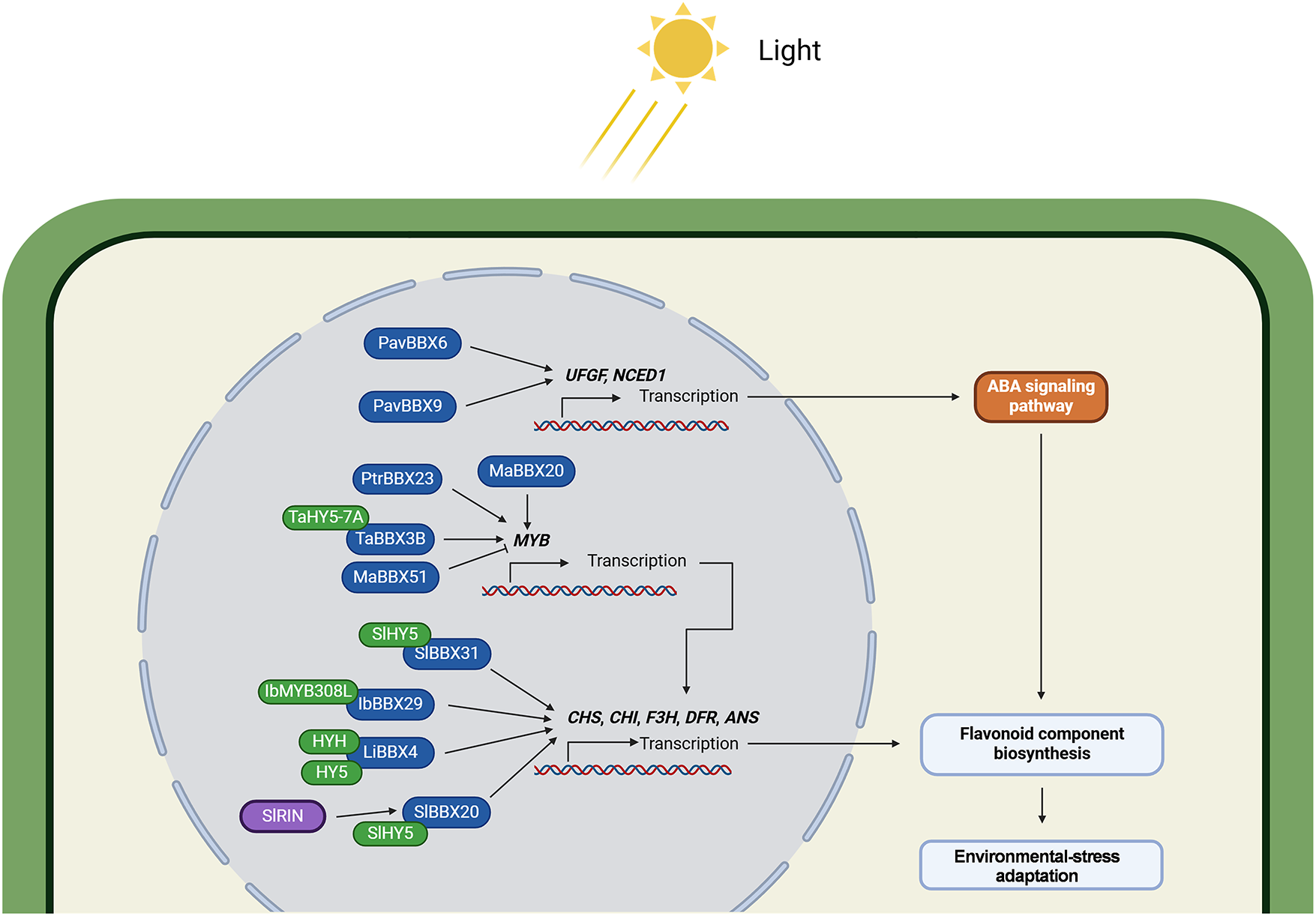

The accumulation of flavonoids (e.g., anthocyanins, proanthocyanidins, and isoflavones) constitutes a fundamental photoprotective mechanism in plants. BBX proteins regulate this process by directly activating genes encoding flavonoid biosynthetic enzymes and their transcriptional regulators (Fig. 5). In tomato, the ripening regulator Ripening Inhibitor (RIN) induces the expression of SlBBX20 in fruits, which subsequently upregulates key flavonoid pathway genes, leading to enhanced flavonoid production [87]. Evolutionarily conserved mechanisms are evident across diverse plant species, with BrBBX21, MdBBX22, LiBBX4, and PtrBBX23 each stimulating foliar anthocyanin biosynthesis via activation of conserved downstream transcriptional networks [20,88,89].

Figure 5: BBX-mediated regulation of flavonoid biosynthesis in plant stress adaptation. Flavonoids function as key phytochemical defenses against environmental stresses. Light-activated BBX proteins transcriptionally coordinate flavonoid biosynthesis through direct regulation of flavonoid biosynthetic enzymes, MYB transcriptional regulators, and ABA-dependent signaling cascades. PavBBX6/9 enhances environmental adaptability by activating the ABA signaling pathway through upregulation of UFGF and NCED1, thereby promoting the biosynthesis of flavonoid compounds. MaBBX20, PtrBBX23, and TaBBX3B increase flavonoid accumulation by activating the expression of MYB genes, which in turn promotes the expression of flavonoid synthase genes. In contrast, MaBBX51 reduces flavonoid accumulation by suppressing MYB expression. SlBBX31, IbBBX29, LiBBX4, and SlBBX20 enhance flavonoid accumulation by promoting the expression of flavonoid synthase genes. Among these, TaBBX3B, SlBBX31, IbBBX29, LiBBX4, and SlBBX20 function through interactions with HY5 or HYH. Additionally, the expression of SlBBX20 is induced by SlRIN. The protein prefixes denote the following species: Pav, Prunus avium cv. Rainier; Ptr, Poncirus trifoliata; Ma, Muscari armeniacum; Ta, Triticum aestivum; Sl, Solanum lycopersicum; Ib, Ipomoea batatas; Li, Lagerstroemia indica. The schematic model was created in BioRender. Lin, C. (2025) https://BioRender.com/l33w68p (accessed on 03 August 2025)

MYB transcription factors serve as master regulators of anthocyanin biosynthesis [90]. BrBBX21 [88], IbBBX29 [91], MaBBX51 [92], PtrBBX23 [89] fine-tune anthocyanin accumulation by transcriptionally activating MYB genes. Moreover, some BBX proteins physically interact with MYB transcription factors to synergistically upregulate anthocyanin biosynthetic genes. During grape berry maturation, PavBBX6/9 positively regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis by directly activating the expression of UDP-Flavonoid Glucosyltransferase (PavUFGT) and 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid Dioxygenase 1 (PavNCED1) [93]. In contrast, soybean (Glycine max) GmBBX4 forms protein complexes with Starch-Free 1/2 (GmSTF1/2), transcriptional activators of isoflavone biosynthesis, to negatively regulate isoflavone production, thereby modulating plant responses to biotic and abiotic stress [94]. In sweet potato, IbBBX29 cooperates with IbMYB308L to activate the promoters of Chalcone Synthase 1 (IbCHS), Chalcone Isomerase 1 (IbCHI1), and Flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase (IbF3′H) through direct binding to their T/G-box cis-elements, ultimately driving flavonoid accumulation in leaves [91]. In grape hyacinth (Muscari armeniacum), MaBBX20 interacts with MaHY5 to form a MaBBX20-MaHY5 complex that activates MaMybA and Dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (MaDFR) transcription, thereby promoting anthocyanin biosynthesis. In contrast, MaBBX51 competes with MaBBX20 for binding to MaHY5, effectively disrupting the MaBBX20–MaHY5 transcriptional activation complex and leading to suppressed expression of MaMybA and MaDFR. Moreover, MaBBX51 directly interacts with MaMybA, preventing its binding to both its autoregulatory promoter and the MaDFR promoter, thereby exerting a dual-layer inhibitory effect on anthocyanin biosynthesis [92]. Similarly, TaBBX3B interacts with TaHY5-7A to co-activate Purple Pericarp-MYB 1 (TaPpm1) expression, enhancing light-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in purple-pericarp wheat [95].

The BBX protein regulates shade avoidance-related phenotypes in plants, such as stem elongation and flowering time, by integrating light signals (e.g., red/far-red ratio) and hormone signals (e.g., gibberellin, auxin) [1]. Under insufficient light conditions, plants exhibit shade avoidance responses, characterized by phenotypes such as elongated hypocotyls and petioles, early flowering, and premature senescence [96]. BBX proteins participate in the regulation of shade avoidance responses by engaging in signaling processes mediated by core components of light response, including phytochrome phyB, cryptochromes CRY1/2, COP1, and HY5 [52]. In Arabidopsis, AtBBX21 and AtBBX22 mediate shade responses through AtCOP1 signaling [97], while AtBBX24 and AtBBX25 interact with AtHY5, negatively regulating AtBBX22 expression to suppress seedling photomorphogenesis [98]. AtBBX16, a direct target gene of the GLK1 transcription factor, participates in cotyledon development and seedling de-etiolation [99].

3.5 Functional Mechanisms of the BBX Gene Family in Biotic Stress Responses

Emerging evidence demonstrates that BBX proteins play crucial roles in plant biotic stress responses. In banana (Musa acuminata), the expression of MaCOL1 is highly induced upon infection by the fungal pathogen Colletotrichum musae [100]. Similarly, multiple BvBBX genes display differential expression patterns in sugar beet (Beta vulgaris) during Cercospora infection [26]. Following Arthrinium phaeospermum inoculation, a total number of 21 BdBBX genes are differentially regulated in Bambusa pervariabilis × Dendrocalamopsis grandis hybrids [40]. These findings collectively indicate the central involvement of BBX family members in coordinating defense responses to multiple biotic stresses.

In cucumber, CsCOL9-silenced plants exhibit increased susceptibility to whitefly (Bemisia tabaci), accompanied by downregulation of defense-related genes (SOD, Respiratory Burst Oxidase Homologue (RBOH), POD), reduced SOD and POD enzyme activities, and decreased H2O2 accumulation. In contrast, overexpression of CsCOL9 leads to reduced B. tabaci survival rates and diminished host preference [59]. Similarly, CaBBX14 enhances pepper (Capsicum annuum) resistance to Phytophthora capsici infection through activation of SA signaling-associated defense genes [46]. Furthermore, LpNAC48 and LpBBX28 synergistically regulate trichome development in Lilium pumilum, potentially contributing to defense against aphids and other herbivorous pests [101]. The IbBBX24 protein in sweet potato enhances resistance to Fusarium wilt by positively regulating the JA signaling pathway. IbBBX24 directly binds to the promoters of the JA signaling repressor IbJAZ10 and the activator IbMYC2, repressing and promoting their transcription, respectively. Through physical interaction with the IbJAZ10 protein, it relieves the suppression of IbMYC2, ultimately activating the expression of JA-responsive genes. Overexpression of IbBBX24 not only significantly improves plant resistance to Fusarium wilt but also increases storage root yield [102].

4 Application and Future Perspectives of B-box Gene Family in Molecular Breeding

As central regulators of plant stress responses, transcription factors integrate hormonal signals and environmental cues to orchestrate the activation of downstream gene networks. These networks encompass antioxidant enzymes, osmolytes, and protective proteins, enabling the precise coordination of adaptive development and defense mechanisms at multiple levels [103,104]. Extensive functional characterization of BBX proteins has been established in both plant developmental processes and environmental stress responses. The BBX gene family constitutes a central regulatory hub coordinating plant light signaling and stress assimilation, demonstrating considerable potential for molecular breeding applications. This review comprehensively synthesizes current knowledge demonstrating that genetic manipulation of BBX genes significantly enhances plant stress resilience, underscoring their potential as key targets for crop improvement strategies. Nevertheless, several critical knowledge gaps persist in BBX-mediated molecular breeding.

(1) The regulatory mechanisms governed by BBX proteins involve intricate crosstalk complexity. BBX transcription factors serve as pleiotropic regulators that orchestrate interconnected networks governing both photomorphogenesis and abiotic stress adaptation. Plants inherently face a fundamental growth-defense trade-off due to finite resource allocation [105]. However, studies in sweet potato have revealed that IbBBX24 not only enhances disease resistance but also improves yield [102], indicating that its functional outcomes are likely context-dependent. BBX members are well-documented mediators of stress adaptation, yet their impact on yield-related traits in standard agronomic settings requires systematic evaluation [69,82]. This functional duality raises a critical question for translational applications: Through what molecular mechanisms can we selectively harness BBX-mediated stress resilience while circumventing detrimental trade-offs in photophysiological and agronomic traits?

(2) Despite their established regulatory roles, the molecular mechanisms governing BBX-mediated hormonal crosstalk remain poorly understood. Current evidence suggests BBX transcription factors interface with ABA, JA, SA and GA signaling through different putative mechanisms. While some studies have explored changes in BBX expression levels in response to hormone treatments [5,31,106], few reports elucidate the mechanistic basis of BBX-mediated hormone signaling. In apple, JA activates its receptor to trigger proteasomal degradation of JAZ1/2 repressors, thereby releasing transcriptional repression of BBX genes [56]. However, the molecular determinants governing pathway specificity and the spatiotemporal dynamics of these regulatory networks remain largely unknown.

(3) Research on BBX-mediated stress tolerance remains confined to controlled conditions, with limited field evaluations. Although BBX proteins have been widely shown to confer stress resilience (particularly to drought and salinity) in controlled conditions, the critical lack of field performance data hinders the translation of these findings into practical agricultural applications. Currently, only two documented cases provide field validation. Overexpression of AtBBX32 in soybean achieved a 10%–15% grain yield increase in multi-location field trials [107]. In addition, it was reported that there was an increased spikelet nodes and tillers in TaCol-B5-overexpressing wheat under preliminary field conditions [108]. Therefore, a comprehensive evaluation of genotype-by-environment interactions and multifactorial stress responses becomes essential to mitigate potential pleiotropic effects.

(4) The potential roles of BBX proteins in plant immunity against economically important pathogens (e.g., Puccinia triticina, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, Rhizoctonia solani) remain unexplored. In pepper, the expression of CaBBX14 improves the resistance to Phytophthora capsica [46]. In addition, CsCOL9 positively regulates resistance of cucumber plant to B. tabaci [59]. Although these studies clearly establish BBX proteins as participants in plant immunity, the exact molecular mechanisms underlying their regulatory functions remain unresolved.

Future integration of deep learning-based gene regulatory network prediction with AI-accelerated protein structure modeling will revolutionize precision molecular design in plants. As central hubs coordinating multiple stress response pathways, BBX transcription factors represent prime targets for developing next-generation stress-adaptive crops. Building on these functional insights, CRISPR-mediated gene editing, base substitution, and promoter engineering offer highly promising avenues for the precise manipulation of BBX genes, enabling tailored enhancements in both stress resilience and agronomic traits. Furthermore, elucidation of BBX protein structures will enable AI-assisted protein directed evolution, providing an innovative approach to optimize BBX molecular functions for enhanced crop environmental adaptation. Nonetheless, translating these advances from controlled laboratory conditions to field applications remains a major challenge, requiring thorough evaluation of phenotypic stability and yield performance under complex environmental conditions. Elucidation of their mechanistic principles spanning from molecular interactions to systems-level regulatory networks will establish a transformative framework for engineering climate-resilient agricultural systems.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research is funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 32301870 and 32572302 to Chen Lin), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (grant No. BK20230568 to Chen Lin), the Jiangsu Provincial Agricultural Science and Technology Independent Innovation Fund (grant No. CX(24)3124 to Chen Lin), Outstanding Ph.D. Program in Yangzhou (grant No. YZLYJFJH2022YXBS147 to Chen Lin), the General Project of Basic Scientific Research to colleges and universities in Jiangsu Province (grant No. 22KJB210019 to Chen Lin), and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions is greatly acknowledged.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Qinfu Sun and Chen Lin; writing—original draft preparation, Qinfu Sun, Junqiang Xing and Wanyu Zhang; writing—review and editing, Chen Lin; supervision, Chen Lin. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data are included in this article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| ABA | Abscisic Acid |

| APX2 | Cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase 2 |

| BBX | B-box |

| CAT | Catalase |

| CBF | C-repeat Binding Factor |

| CHI | Chalcone Isomerase |

| CHS | Chalcone Synthase 1 |

| COL | CONSTANS-like |

| COP1 | Constitutively Photomorphogenic 1 |

| COR | Cold Regulated gene |

| CRY2 | Cryptochrome 2 |

| CSLG2 | Cellulose synthase-like protein G2 |

| DFR | Dihydroflavonol 4-reductase |

| DGD1 | Digalactosyldiacylglycerol Synthase 1 |

| ERD15 | Early Responsive to Dehydration 15 |

| ERF1 | Ethylene Response Factor 1 |

| F3H | Flavanone 3-Hydroxylase |

| FLS | Flavonol Synthase |

| GA | Gibberellin acid |

| GLK1 | Golden2-like 1 |

| Hsp70/101 | Heat shock protein 70/101 |

| HY5 | Elongated Hypocotyl 5 |

| HYH | Homolog of HY5 |

| HsfA2 | Heat shock factor A2 |

| ICE1 | Inducer of CBF Expression 1 |

| JA | Jasmonate Acid |

| JAZ1/2 | Jasmonate-Zim-Domain Protein 1/2 |

| MIEL1 | MYB30-Interacting E3 Ligase 1 |

| MPK1/2 | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase 1/2 |

| NCED1 | 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase 1 |

| PIF | Phytochrome Interacting Factor |

| POD | Peroxidase |

| Ppm1 | Purple Pericarp-MYB 1 |

| RAB18 | Responsive to ABA 18 |

| RD29B | Responsive to Desiccation 29B |

| RIN | Ripening Inhibitor |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SA | Salicylic Acid |

| SAG29 | Senescence-Associated gene 29 |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| STF1/2 | Starch-Free 1/2 |

| UFGT | UDP-flavonoid glucosyltransferase |

| UVR1/3 | UV Repair Defective 1/3 |

References

1. Gangappa SN, Botto JF. The BBX family of plant transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2014;19(7):460–70. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2014.01.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Liu J, Zhang C, Wang X, Hu W, Feng Z. Tumor suppressor p53 cross-talks with TRIM family proteins. Genes Dis. 2020;8(4):463–74. doi:10.1016/j.gendis.2020.07.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Khanna R, Kronmiller B, Maszle DR, Coupland G, Holm M, Mizuno T, et al. The Arabidopsis B-box zinc finger family. Plant Cell. 2009;21(11):3416–20. doi:10.1105/tpc.109.069088. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Song Z, Bian Y, Xiao Y, Xu D. B-BOX proteins: multi-layered roles of molecular cogs in light-mediated growth and development in plants. J Plant Physiol. 2024;299:154265. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2024.154265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Vaishak KP, Yadukrishnan P, Bakshi S, Kushwaha AK, Ramachandran H, Job N, et al. The B-box bridge between light and hormones in plants. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2019;191:164–74. doi:10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.12.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Yang L, Fang S, Liu L, Zhao L, Chen W, Li X, et al. WRKY transcription factors: hubs for regulating plant growth and stress responses. J Integr Plant Biol. 2025;67(3):488–509. doi:10.1111/jipb.13828. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Xiong H, He H, Chang Y, Miao B, Liu Z, Wang Q, et al. Multiple roles of NAC transcription factors in plant development and stress responses. J Integr Plant Biol. 2025;67(3):510–38. doi:10.1111/jipb.13854. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Ma Z, Hu L, Zhong Y. Structure, evolution, and roles of MYB transcription factors proteins in secondary metabolite biosynthetic pathways and abiotic stresses responses in plants: a comprehensive review. Front Plant Sci. 2025;16:1626844. doi:10.3389/fpls.2025.1626844. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Strayer C, Oyama T, Schultz TF, Raman R, Somers DE, Más P, et al. Cloning of the Arabidopsis clock gene TOC1 an autoregulatory response regulator homolog. Science. 2000;289(5480):768–71. doi:10.1126/science.289.5480.768. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Putterill J, Robson F, Lee K, Simon R, Coupland G. The CONSTANS gene of Arabidopsis promotes flowering and encodes a protein showing similarities to zinc finger transcription factors. Cell. 1995;80(6):847–57. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(95)90288-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Robson F, Costa MM, Hepworth SR, Vizir I, Piñeiro M, Reeves PH, et al. Functional importance of conserved domains in the flowering-time gene CONSTANS demonstrated by analysis of mutant alleles and transgenic plants. Plant J. 2001;28(6):619–31. doi:10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01163.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Cao Y, Meng D, Han Y, Chen T, Jiao C, Chen Y, et al. Comparative analysis of B-BOX genes and their expression pattern analysis under various treatments in Dendrobium officinale. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19(1):245. doi:10.1186/s12870-019-1851-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Crocco CD, Botto JF. BBX proteins in green plants: insights into their evolution, structure, feature and functional diversification. Gene. 2013;531(1):44–52. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2013.08.037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Wang Y, Zhang Y, Liu Q, Zhang T, Chong X, Yuan H. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of BBX transcription factors in Iris germanica L. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(16):8793. doi:10.3390/ijms22168793. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Chen S, Qiu Y, Lin Y, Zou S, Wang H, Zhao H, et al. Genome-wide identification of B-box family genes and their potential roles in seed development under shading conditions in rapeseed. Plants. 2024;13(16):2226. doi:10.3390/plants13162226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Wu J, Zhang M, Gao Y, Li S, Jia R, Zhang L. Genome-wide characterization and expression analysis of the CONSTANS-like gene family of Juglans mandshurica Maxim. PeerJ. 2025;13(8):e19169. doi:10.7717/peerj.19169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Wang W, Liu X, Liu C, Liu X. Genome-wide analysis and expression profiles of AhCOLs family in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(7):3404. doi:10.3390/ijms26073404. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Wu R, Li Y, Wang L, Li Z, Wu R, Xu K, et al. The DBB family in Populus trichocarpa: identification, characterization, evolution and expression profiles. Molecules. 2024;29(8):1823. doi:10.3390/molecules29081823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Bu X, Wang X, Yan J, Zhang Y, Zhou S, Sun X, et al. Genome-wide characterization of B-box gene family and its roles in responses to light quality and cold stress in tomato. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:698525. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.698525. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Deng F, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Li Y, Li L, Lei Y, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the BBX gene family in Lagerstroemia indica grown under light stress. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025;297(23):139899. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.139899. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Zheng LW, Ma SJ, Zhou T, Yue CP, Hua YP, Huang JY. Genome-wide identification of Brassicaceae B-BOX genes and molecular characterization of their transcriptional responses to various nutrient stresses in allotetraploid rapeseed. BMC Plant Biol. 2021;21(1):288. doi:10.1186/s12870-021-03043-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Wang Y, Qin H, Ni J, Yang T, Lv X, Ren K, et al. Genome-wide identification, characterization and expression patterns of the DBB transcription factor family genes in wheat. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(21):11654. doi:10.3390/ijms252111654. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Shalmani A, Jing XQ, Shi Y, Muhammad I, Zhou MR, Wei XY, et al. Characterization of B-BOX gene family and their expression profiles under hormonal, abiotic and metal stresses in Poaceae plants. BMC Genomics. 2019;20(1):27. doi:10.1186/s12864-018-5336-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Xue Y, Chen J, Hao J, Bao X, Kuang L, Zhang D, et al. Identification of the BBX gene family in blueberry at different chromosome ploidy levels and fruit development and response under stress. BMC Genomics. 2025;26(1):100. doi:10.1186/s12864-025-11273-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Cheng X, Lei S, Li J, Tian B, Li C, Cao J, et al. In silico analysis of the wheat BBX gene family and identification of candidate genes for seed dormancy and germination. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24(1):334. doi:10.1186/s12870-024-04977-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Song H, Ding G, Zhao C, Li Y. Genome-wide identification of B-box gene family and expression analysis suggest its roles in responses to Cercospora leaf spot in sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.). Genes. 2023;14(6):1248. doi:10.3390/genes14061248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Ouyang Y, Pan X, Wei Y, Wang J, Xu X, He Y, et al. Genome-wide identification and characterization of the BBX gene family in pineapple reveals that candidate genes are involved in floral induction and flowering. Genomics. 2022;114(4):110397. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2022.110397. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Obel HO, Cheng C, Li Y, Tian Z, Njogu MK, Li J, et al. Genome-wide identification of the B-box gene family and expression analysis suggests their potential role in photoperiod-mediated β-carotene accumulation in the endocarp of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) fruit. Genes. 2022;13(4):658. doi:10.3390/genes13040658. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Li W, Xiong R, Chu Z, Peng X, Cui G, Dong L. Transcript-wide identification and characterization of the BBX gene family in Trichosanthes kirilowii and its potential roles in development and abiotic stress. Plants. 2025;14(6):975. doi:10.3390/plants14060975. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Xu Z, Zhang G, Chen J, Ying Y, Yao L, Li X, et al. Role of Rubus chingii BBX gene family in anthocyanin accumulation during fruit ripening. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1427359. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1427359. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Wang X, Guo H, Jin Z, Ding Y, Guo M. Comprehensive characterization of B-box zinc finger genes in Citrullus lanatus and their response to hormone and abiotic stresses. Plants. 2023;12(14):2634. doi:10.3390/plants12142634. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Shi K, Zhao G, Li Z, Zhou J, Wu L, Tan X, et al. Genome-wide identification of B-box gene family and candidate light-related member analysis of tung tree (Vernicia fordii). Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(4):1977. doi:10.3390/ijms25041977. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Wang J, Meng Z, He H, Du P, Dijkwel PP, Shi S, et al. Genome-wide analysis of BBX gene family in three Medicago species provides insights into expression patterns under hormonal and salt stresses. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(11):5778. doi:10.3390/ijms25115778. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Yin L, Wu R, An R, Feng Y, Qiu Y, Zhang M. Genome-wide identification, molecular evolution and expression analysis of the B-box gene family in mung bean (Vigna radiata L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24(1):532. doi:10.1186/s12870-024-05236-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Nian L, Zhang X, Liu X, Li X, Liu X, Yang Y, et al. Characterization of B-box family genes and their expression profiles under abiotic stresses in the Melilotus albus. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:990929. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.990929. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Li Y, Tong Y, Ye J, Zhang C, Li B, Hu S, et al. Genome-wide characterization of B-box gene family in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(3):2146. doi:10.3390/ijms24032146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Feng Z, Li M, Li Y, Yang X, Wei H, Fu X, et al. Comprehensive identification and expression analysis of B-Box genes in cotton. BMC Genomics. 2021;22(1):439. doi:10.1186/s12864-021-07770-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Deng H, Zhang Y, Manzoor MA, Ali Sabir I, Han B, Song C. Genome-scale identification, expression and evolution analysis of B-box members in Dendrobium huoshanense. Heliyon. 2024;10(12):e32773. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e32773. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Shi G, Ai K, Yan X, Zhou Z, Cai F, Bao M, et al. Genome-wide analysis of the BBX genes in Platanus × acerifolia and their relationship with flowering and/or dormancy. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(10):8576. doi:10.3390/ijms24108576. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Liu Y, Wang Y, Liao J, Chen Q, Jin W, Li S, et al. Identification and characterization of the BBX gene family in Bambusa pervariabilis × Dendrocalamopsis grandis and their potential role under adverse environmental stresses. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(17):13465. doi:10.3390/ijms241713465. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Ma R, Chen J, Huang B, Huang Z, Zhang Z. The BBX gene family in Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulisidentification, characterization and expression profiles. BMC Genomics. 2021;22(1):533. doi:10.1186/s12864-021-07821-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Wu Z, Fu D, Gao X, Zeng Q, Chen X, Wu J, et al. Characterization and expression profiles of the B-box gene family during plant growth and under low-nitrogen stress in Saccharum. BMC Genomics. 2023;24(1):79. doi:10.1186/s12864-023-09185-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Liu X, Li R, Dai Y, Chen X, Wang X. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the B-box gene family in the Apple (Malus domestica Borkh.) genome. Mol Genet Genom. 2018;293(2):303–15. doi:10.1007/s00438-017-1386-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Wang Y, Zhai Z, Sun Y, Feng C, Peng X, Zhang X, et al. Genome-wide identification of the B-BOX genes that respond to multiple ripening related signals in sweet cherry fruit. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(4):1622. doi:10.3390/ijms22041622. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Zhang Q, Ma D, Hu Z, Zong D, He C. PyunBBX18 is involved in the regulation of anthocyanins biosynthesis under UV-B stress. Genes. 2022;13(10):1811. doi:10.3390/genes13101811. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Zhou Y, Li Y, Yu T, Li J, Qiu X, Zhu C, et al. Characterization of the B-BOX gene family in pepper and the role of CaBBX14 in defense response against Phytophthora capsici infection. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;237:124071. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.124071. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Wen S, Zhang Y, Deng Y, Chen G, Yu Y, Wei Q. Genomic identification and expression analysis of the BBX transcription factor gene family in Petunia hybrida. Mol Biol Rep. 2020;47(8):6027–41. doi:10.1007/s11033-020-05678-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Talar U, Kiełbowicz-Matuk A, Czarnecka J, Rorat T. Genome-wide survey of B-box proteins in potato (Solanum tuberosum)—Identification, characterization and expression patterns during diurnal cycle, etiolation and de-etiolation. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0177471. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0177471. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Song K, Li B, Wu H, Sha Y, Qin L, Chen X, et al. The function of BBX gene family under multiple stresses in Nicotiana tabacum. Genes. 2022;13(10):1841. doi:10.3390/genes13101841. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Yin Y, Shi H, Mi J, Qin X, Zhao J, Zhang D, et al. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the BBX gene family and its role in carotenoid biosynthesis in wolfberry (Lycium barbarum L.). Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(15):8440. doi:10.3390/ijms23158440. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Zhang X, Zhang L, Ji M, Wu Y, Zhang S, Zhu Y, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the B-box transcription factor gene family in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.). BMC Genomics. 2021;22(1):221. doi:10.1186/s12864-021-07479-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Cao J, Yuan J, Zhang Y, Chen C, Zhang B, Shi X, et al. Multi-layered roles of BBX proteins in plant growth and development. Stress Biol. 2023;3(1):1. doi:10.1007/s44154-022-00080-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Tripathi P, Carvallo M, Hamilton EE, Preuss S, Kay SA. Arabidopsis B-BOX32 interacts with CONSTANS-LIKE3 to regulate flowering. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(1):172–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.1616459114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Song Z, Yan T, Liu J, Bian Y, Heng Y, Fang L, et al. BBX28/BBX29, HY5 and BBX30/31 form a feedback loop to fine-tune photomorphogenic development. Plant J. 2020;104(2):377–90. doi:10.1111/tpj.14929. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Xu D, Jiang Y, Li J, Lin F, Holm M, Deng XW. BBX21, an Arabidopsis B-box protein, directly activates HY5 and is targeted by COP1 for 26S proteasome-mediated degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(27):7655–60. doi:10.1073/pnas.1607687113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. An JP, Wang XF, Zhang XW, You CX, Hao YJ. Apple B-box protein BBX37 regulates jasmonic acid mediated cold tolerance through the JAZ-BBX37-ICE1-CBF pathway and undergoes MIEL1-mediated ubiquitination and degradation. New Phytol. 2021;229(5):2707–29. doi:10.1111/nph.17050. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Song J, Lin R, Tang M, Wang L, Fan P, Xia X, et al. SlMPK1- and SlMPK2-mediated SlBBX17 phosphorylation positively regulates CBF-dependent cold tolerance in tomato. New Phytol. 2023;239(5):1887–902. doi:10.1111/nph.19072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Shen T, Xu F, Chen D, Yan R, Wang Q, Li K, et al. A B-box transcription factor OsBBX17 regulates saline-alkaline tolerance through the MAPK cascade pathway in rice. New Phytol. 2024;241(5):2158–75. doi:10.1111/nph.19480. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Xie S, Shi B, Miao M, Zhao C, Bai R, Yan F, et al. A B-box (BBX) transcription factor from cucumber, CsCOL9 positively regulates resistance of host plant to Bemisia tabaci. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(1):324. doi:10.3390/ijms26010324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Min JH, Chung JS, Lee KH, Kim CS. The CONSTANS-like 4 transcription factor, AtCOL4, positively regulates abiotic stress tolerance through an abscisic acid-dependent manner in Arabidopsis. J Integr Plant Biol. 2015;57(3):313–24. doi:10.1111/jipb.12246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Xu D, Li J, Gangappa SN, Hettiarachchi C, Lin F, Andersson MX, et al. Convergence of light and ABA signaling on the ABI5 promoter. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(2):e1004197. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Datta S, Hettiarachchi C, Johansson H, Holm M. SALT TOLERANCE HOMOLOG2, a B-box protein in Arabidopsis that activates transcription and positively regulates light-mediated development. Plant Cell. 2007;19(10):3242–55. doi:10.1105/tpc.107.054791. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Zeng X, Lv X, Liu R, He H, Liang S, Chen L, et al. Molecular basis of CONSTANS oligomerization in FLOWERING LOCUS T activation. J Integr Plant Biol. 2022;64(3):731–40. doi:10.1111/jipb.13223. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Zhang H, Wang Z, Li X, Gao X, Dai Z, Cui Y, et al. The IbBBX24-IbTOE3-IbPRX17 module enhances abiotic stress tolerance by scavenging reactive oxygen species in sweet potato. New Phytol. 2022;233(3):1133–52. doi:10.1111/nph.17860. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Dong J, Zhao C, Zhang J, Ren Y, He L, Tang R, et al. The sweet potato B-box transcription factor gene IbBBX28 negatively regulates drought tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Front Genet. 2022;13:1077958. doi:10.3389/fgene.2022.1077958. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Tang H, Yuan C, Shi H, Liu F, Shan S, Wang Z, et al. Genome-wide identification of peanut B-boxs and functional characterization of AhBBX6 in salt and drought stresses. Plants. 2024;13(7):955. doi:10.3390/plants13070955. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Wu H, Wang X, Cao Y, Zhang H, Hua R, Liu H, et al. CpBBX19, a B-box transcription factor gene of Chimonanthus praecox, improves salt and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis. Genes. 2021;12(9):1456. doi:10.3390/genes12091456. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Mbambalala N, Panda SK, van der Vyver C. Overexpression of AtBBX29 improves drought tolerance by maintaining photosynthesis and enhancing the antioxidant and osmolyte capacity of sugarcane plants. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2021;39(2):419–33. doi:10.1007/s11105-020-01261-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Chen P, Zhi F, Li X, Shen W, Yan M, He J, et al. Zinc-finger protein MdBBX7/MdCOL9, a target of MdMIEL1 E3 ligase, confers drought tolerance in apple. Plant Physiol. 2022;188(1):540–59. doi:10.1093/plphys/kiab420. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Xu Y, Zhao X, Aiwaili P, Mu X, Zhao M, Zhao J, et al. A zinc finger protein BBX19 interacts with ABF3 to affect drought tolerance negatively in Chrysanthemum. Plant J. 2020;103(5):1783–95. doi:10.1111/tpj.14863. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Liu Y, Chen H, Ping Q, Zhang Z, Guan Z, Fang W, et al. The heterologous expression of CmBBX22 delays leaf senescence and improves drought tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 2019;38(1):15–24. doi:10.1007/s00299-018-2345-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Yang Y, Ma C, Xu Y, Wei Q, Imtiaz M, Lan H, et al. A zinc finger protein regulates flowering time and abiotic stress tolerance in Chrysanthemum by modulating gibberellin biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 2014;26(5):2038–2054. doi:10.1105/tpc.114.124867. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Riboni M, Robustelli Test A, Galbiati M, Tonelli C, Conti L. ABA-dependent control of GIGANTEA signalling enables drought escape via up-regulation of FLOWERING LOCUS T in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Exp Bot. 2016;67(22):6309–22. doi:10.1093/jxb/erw384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Lippuner V, Cyert MS, Gasser CS. Two classes of plant cDNA clones differentially complement yeast calcineurin mutants and increase salt tolerance of wild-type yeast. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(22):12859–66. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.22.12859. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Zhang Y, Liu X, Shi Y, Lang L, Tao S, Zhang Q, et al. The B-box transcription factor BnBBX22.A07 enhances salt stress tolerance by indirectly activating BnWRKY33.C03. Plant Cell Environ. 2024;47(12):5424–42. doi:10.1111/pce.15119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Lei L, Cao L, Ding G, Zhou J, Luo Y, Bai L, et al. OsBBX11 on qSTS4 links to salt tolerance at the seeding stage in Oryza sativa L. ssp. Japonica. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1139961. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1139961. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Kiełbowicz-Matuk A, Grądzka K, Biegańska M, Talar U, Czarnecka J, Rorat T. The StBBX24 protein affects the floral induction and mediates salt tolerance in Solanum tuberosum. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:965098. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.965098. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Huang S, Chen C, Xu M, Wang G, Xu LA, Wu Y. Overexpression of Ginkgo BBX25 enhances salt tolerance in Transgenic Populus. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021;167:946–54. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.09.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Liu X, Li R, Dai Y, Yuan L, Sun Q, Zhang S, et al. A B-box zinc finger protein, MdBBX10, enhanced salt and drought stresses tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol. 2019;99(4):437–47. doi:10.1007/s11103-019-00828-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Kobayashi M, Horiuchi H, Fujita K, Takuhara Y, Suzuki S. Characterization of grape C-repeat-binding factor 2 and B-box-type zinc finger protein in transgenic Arabidopsis plants under stress conditions. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39(8):7933–9. doi:10.1007/s11033-012-1638-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Meena SK, Quevedo M, Nardeli SM, Verez C, Bhat SS, Zacharaki V, et al. Antisense transcription from stress-responsive transcription factors fine-tunes the cold response in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2024;36(9):3467–82. doi:10.1093/plcell/koae160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Li Y, Shi Y, Li M, Fu D, Wu S, Li J, et al. The CRY2-COP1-HY5-BBX7/8 module regulates blue light-dependent cold acclimation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2021;33(11):3555–73. doi:10.1093/plcell/koab215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Wang Q, Zhan X. Elucidating the role of SlBBX31 in plant growth and heat-stress resistance in tomato. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(17):9289. doi:10.3390/ijms25179289. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Wang Q, Tu X, Zhang J, Chen X, Rao L. Heat stress-induced BBX18 negatively regulates the thermotolerance in Arabidopsis. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40(3):2679–88. doi:10.1007/s11033-012-2354-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Xu X, Wang Q, Li W, Hu T, Wang Q, Yin Y, et al. Overexpression of SlBBX17 affects plant growth and enhances heat tolerance in tomato. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;206(3):799–811. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.03.080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Job N, Dwivedi S, Lingwan M, Datta S. BBX22 enhances the accumulation of antioxidants to inhibit DNA damage and promotes DNA repair under high UV-B. Physiol Plant. 2025;177(1):e70038. doi:10.1111/ppl.70038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Shiose L, dos Reis Moreira J, Lira BS, Ponciano G, Gómez-Ocampo G, Wu RTA, et al. A tomato B-box protein regulates plant development and fruit quality through the interaction with PIF4, HY5, and RIN transcription factors. J Exp Bot. 2024;75(11):3368–87. doi:10.1093/jxb/erae119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Fu M, Lu M, Guo J, Jiang S, Khan I, Karamat U, et al. Molecular functional and transcriptome analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana overexpression BrBBX21 from zicaitai (Brassica rapa var. purpuraria). Plants. 2024;13(23):3306. doi:10.3390/plants13233306. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Li C, Pei J, Yan X, Cui X, Tsuruta M, Liu Y, et al. A poplar B-box protein PtrBBX23 modulates the accumulation of anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins in response to high light. Plant Cell Environ. 2021;44(9):3015–33. doi:10.1111/pce.14127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Ma D, Constabel CP. MYB repressors as regulators of phenylpropanoid metabolism in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2019;24(3):275–89. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2018.12.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Gao XR, Zhang H, Li X, Bai YW, Peng K, Wang Z, et al. The B-box transcription factor IbBBX29 regulates leaf development and flavonoid biosynthesis in sweet potato. Plant Physiol. 2023;191(1):496–514. doi:10.1093/plphys/kiac516. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Zhang H, Wang J, Tian S, Hao W, Du L. Two B-box proteins, MaBBX20 and MaBBX51, coordinate light-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in grape hyacinth. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(10):5678. doi:10.3390/ijms23105678. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Wang Y, Xiao Y, Sun Y, Zhang X, Du B, Turupu M, et al. Two B-box proteins, PavBBX6/9, positively regulate light-induced anthocyanin accumulation in sweet cherry. Plant Physiol. 2023;192(3):2030–48. doi:10.1093/plphys/kiad137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Song Z, Zhao F, Chu L, Lin H, Xiao Y, Fang Z, et al. The GmSTF1/2-GmBBX4 negative feedback loop acts downstream of blue-light photoreceptors to regulate isoflavonoid biosynthesis in soybean. Plant Commun. 2024;5(2):100730. doi:10.1016/j.xplc.2023.100730. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Jiang Q, Jiang W, Hu N, Tang R, Dong Y, Wu H, et al. Light-induced TaHY5-7A and TaBBX-3B physically interact to promote PURPLE PERICARP-MYB 1 expression in purple-grained wheat. Plants. 2023;12(16):2996. doi:10.3390/plants12162996. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Liu Y, Jafari F, Wang H. Integration of light and hormone signaling pathways in the regulation of plant shade avoidance syndrome. aBIOTECH. 2021;2(2):131–45. doi:10.1007/s42994-021-00038-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Crocco CD, Holm M, Yanovsky MJ, Botto JF. Function of B-BOX under shade. Plant Signal Behav. 2011;6(1):101–4. doi:10.4161/psb.6.1.14185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Gangappa SN, Crocco CD, Johansson H, Datta S, Hettiarachchi C, Holm M, et al. The Arabidopsis B-BOX protein BBX25 interacts with HY5, negatively regulating BBX22 expression to suppress seedling photomorphogenesis. Plant Cell. 2013;25(4):1243–57. doi:10.1105/tpc.113.109751. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Veciana N, Martín G, Leivar P, Monte E. BBX16 mediates the repression of seedling photomorphogenesis downstream of the GUN1/GLK1 module during retrograde signalling. New Phytol. 2022;234(1):93–106. doi:10.1111/nph.17975. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Chen J, Chen JY, Wang JN, Kuang JF, Shan W, Lu WJ. Molecular characterization and expression profiles of MaCOL1, a CONSTANS-like gene in banana fruit. Gene. 2012;496(2):110–7. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2012.01.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Xin Y, Pan W, Zhao Y, Yang C, Li J, Wang S, et al. The NAC transcription factor LpNAC48 promotes trichome formation in Lilium pumilum. Plant Physiol. 2024;197:kiaf001. doi:10.1093/plphys/kiaf001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Zhang H, Zhang Q, Zhai H, Gao S, Yang L, Wang Z, et al. IbBBX24 promotes the jasmonic acid pathway and enhances Fusarium wilt resistance in sweet potato. Plant Cell. 2020;32(4):1102–23. doi:10.1105/tpc.19.00641. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Kim JS, Kidokoro S, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. Regulatory networks in plant responses to drought and cold stress. Plant Physiol. 2024;195(1):170–89. doi:10.1093/plphys/kiae105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Sato H, Mizoi J, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Complex plant responses to drought and heat stress under climate change. Plant J. 2024;117(6):1873–92. doi:10.1111/tpj.16612. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Gao M, Hao Z, Ning Y, He Z. Revisiting growth-defence trade-offs and breeding strategies in crops. Plant Biotechnol J. 2024;22(5):1198–205. doi:10.1111/pbi.14258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Singh S, Chhapekar SS, Ma Y, Rameneni JJ, Oh SH, Kim J, et al. Genome-wide identification, evolution, and comparative analysis of B-box genes in Brassica rapa, B. oleracea, and B. napus and their expression profiling in B. rapa in response to multiple hormones and abiotic stresses. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(19):10367. doi:10.3390/ijms221910367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Preuss SB, Meister R, Xu Q, Urwin CP, Tripodi FA, Screen SE, et al. Expression of the Arabidopsis thaliana BBX32 gene in soybean increases grain yield. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e30717. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030717. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Zhang X, Jia H, Li T, Wu J, Nagarajan R, Lei L, et al. TaCol-B5 modifies spike architecture and enhances grain yield in wheat. Science. 2022;376(6589):180–3. doi:10.1126/science.abm0717. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools