Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Germination and Early Growth Responses of Bread Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) to Cadmium Stress

1 Laboratory of Biotechnology, Agri-food, Materials, and Environment (LBAME), Department of Biology, Faculty of Science and Techniques—Mohammedia, Hassan II University of Casablanca, BP 146, Mohammedia, 28800, Morocco

2 UR Biotechnologie, CRRA-Rabat, Institut National de La Recherche Agronomique, BP 6570, Rabat, 10101, Morocco

* Corresponding Author: Mohamed Ait-El-Mokhtar. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant Responses and Adaptations to Environmental Stresses)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(11), 3687-3701. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.071634

Received 09 August 2025; Accepted 09 October 2025; Issue published 01 December 2025

Abstract

Cadmium (Cd) contamination is a major environmental stressor that adversely affects crop germination and early development. This study assessed the impact of increasing Cd concentrations (0.125 to 1 g/L) on seed germination and early seedling growth in three bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivars: Achtar, Lina, and Snina. The results revealed a clear dose-dependent inhibitory effect of Cd. Germination percentage (GP) significantly declined with increasing Cd levels, while mean germination time was progressively delayed, particularly at higher concentrations. Vigor index (VI) also showed significant reductions, reflecting compromised seedling establishment. Morphological traits, especially shoot and root lengths, were negatively affected, with root systems exhibiting greater sensitivity. Growth inhibition indices indicated a stronger suppression in roots than in shoots, and tolerance index (TI) values demonstrated clear intervarietal differences, with Achtar displaying the highest tolerance and Lina the greatest susceptibility. Pearson correlation analysis revealed strong positive relationships among GP, VI, TI, and seedling length, and negative correlations with shoot and root growth inhibition. Principal component analysis further supported these patterns, effectively separating cultivar responses across treatments. Overall, this study highlights the phytotoxic effects of Cd on early wheat development and underscores the role of genetic variability in determining cultivar tolerance to heavy metal stress.Keywords

Ensuring safe and sustainable crop production is becoming more challenging as agricultural soils face contamination from heavy metals. Among these pollutants, cadmium (Cd) is one of the most hazardous due to its high mobility, persistence in the environment and ability to accumulate in biological organisms [1]. In agricultural systems, Cd contamination arises from multiple sources, including phosphate-based fertilizers, industrial emissions, sewage sludge, the uncontrolled use of untreated wastewater for irrigation, and natural geological sources such as the weathering of parent rock [2,3]. Its accumulation in soil, especially in water-scarce regions where marginal resources are reused, raises serious concerns for food safety and crop viability [4]. In Morocco, concerning levels of Cd contamination have been recorded in agricultural regions such as the Gharb Plain (Mnasra) and Mohammedia–Benslimane, where Cd concentrations in wheat soils exceeded regulatory thresholds, reaching up to 10.4 ppm in some areas [5,6]. Cd’s phytotoxic effects are particularly severe during the first stages of plant development [1], not only impairing visible growth but also disrupting biochemical and molecular processes. In wheat, Cd exposure can trigger excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to oxidative damage in lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids. To counteract this stress, plants activate enzymatic antioxidants such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and ascorbate peroxidase (APX), as well as non-enzymatic antioxidants like glutathione (GSH) [7]. Cadmium also induces the synthesis of phytochelatins, which chelate and sequester the metal in vacuoles [8]. Recent multi-omics studies further reveal that Cd stress alters the expression of metal-transporter genes (e.g., HMA, ABCC, NRAMP families) and reprograms central metabolic pathways, including those involved in sugar, amino acid, and osmolyte biosynthesis, changes that collectively influence germination performance and early seedling establishment [9,10]. These integrated defense mechanisms ultimately influence a seed’s ability to germinate and establish healthy seedlings under Cd stress [11]. Several studies have shown that Cd significantly affects seed germination and early seedling development, which are crucial stages in determining final plant productivity [12–14]. For instance, Lamhamdi et al. [15] demonstrated that Cd reduced the germination percentage and inhibited shoot and root elongation in bread wheat, especially at higher concentrations. Similarly, Shedeed and Farhat [16] observed that Cd stress altered biochemical responses and suppressed seedling vigor in wheat, though some of these effects were alleviated using phytoremediation agents like Azolla pinnata.

Wheat (Triticum spp.), one of the most cultivated cereals globally, is of particular concern due to its widespread consumption and its potential to transfer heavy metals through the food chain [17]. While wheat is known for its adaptability to different soil and climatic conditions, its performance under toxic stress, particularly during the early growth stages, remains genotype-dependent [18,19]. As a staple food, ensuring its safe production is of paramount importance. While Cd concentrations in Moroccan wheat grains may vary regionally [20,21], its ability to accumulate in edible plant parts, including grains, shoots, and leaves, raises concerns about potential entry into the food chain, affecting not only human health but also livestock and broader ecosystems [22].

Germination marks the first and most sensitive stage of plant development, where the seed activates metabolic pathways and begins development into a seedling [23]. This stage can be severely impaired by the presence of toxic elements such as Cd, potentially delaying plant growth, inhibiting root and shoot elongation and reducing seedling vigor, thus affecting the entire plant life cycle [24,25]. In a previous study conducted in our laboratory, we assessed the impact of Cd on the germination and early growth of three durum wheat (Triticum durum L.) cultivars. The results revealed that Cd significantly reduced germination rates, inhibited root, and shoot elongation in a concentration-dependent manner, with root length being more affected than shoot length. Among the tested cultivars, Louiza showed the highest sensitivity [26].

In Morocco, where wheat is a dietary staple and a key component of national food security, understanding its behavior under Cd stress is particularly important. Based on our previous findings in durum wheat and the widespread cultivation of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) in Morocco, we hypothesize that Moroccan bread wheat cultivars may exhibit differential tolerance to Cd stress during germination. Therefore, the objective of this study is to evaluate the germination performance and early growth responses of three bread wheat varieties under increasing Cd concentrations, with the aim of identifying potential varietal tolerance and contributing to future selection strategies for cultivation in contaminated soils.

2.1 Effects of Cd on Wheat Germination

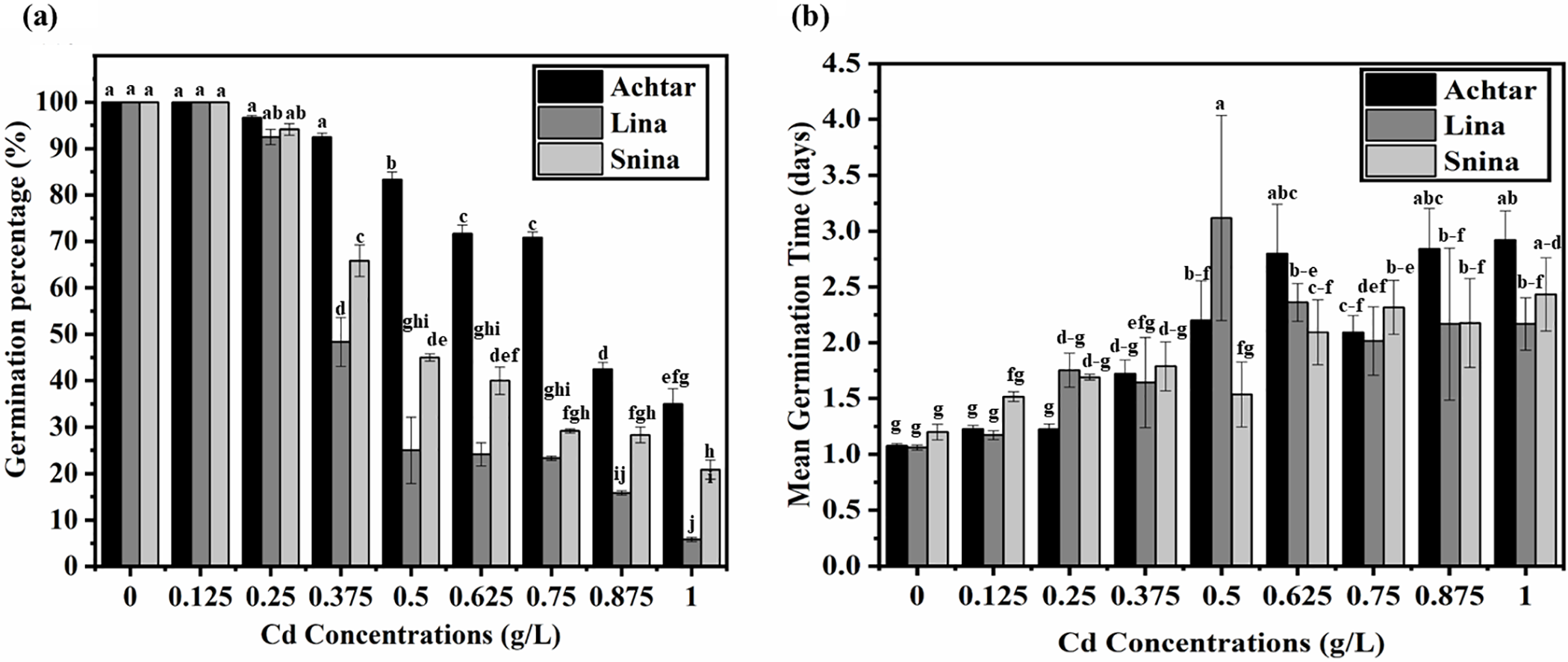

Germination percentage (GP) declined progressively with increasing Cd concentrations, and the magnitude of reduction differed across the three wheat cultivars (Fig. 1a). All cultivars showed full germination (100%) under control and 0.125 g/L Cd. At 0.25 g/L, minor declines emerged, though not statistically significant. From 0.375 g/L onward, differences became more apparent: Achtar maintained higher GP values, while Lina and Snina showed significant reductions (p < 0.05). The most pronounced effects occurred at 0.875 and 1 g/L, where GP dropped sharply in Lina and Snina, whereas Achtar retained higher values throughout.

Figure 1: The impact of Cd on GP and MGT. (a) Germination percentage (%), (b) Mean Germination Time (days). Bars marked with different letters denote statistically significant differences, as determined by Tukey’s post hoc test following a one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05)

Cd stress progressively delayed germination in all cultivars, as reflected in the significant increase in mean germination time (MGT) with rising Cd concentrations (Fig. 1b). Under control conditions, MGT values were low and statistically similar across cultivars. Notably, Snina was the first to exhibit a measurable delay at 0.125 g/L, while Lina and Achtar remained unaffected at that level. As Cd concentrations increased, Lina and Snina showed a stronger delay at 0.25 g/L, whereas Achtar’s response remained mild. At higher concentrations (≥0.5 g/L), Lina exhibited the most pronounced increase in MGT, peaking at 3.12 days, while Achtar and Snina followed with more moderate delays. By 1 g/L, all cultivars experienced significant slowing of germination compared to the control, with Achtar at 2.92 days, Snina at 2.43 days, and Lina at 2.17 days, which is significantly higher and slower than the control (p < 0.05).

2.2 Effect of Cd on Seedling Development

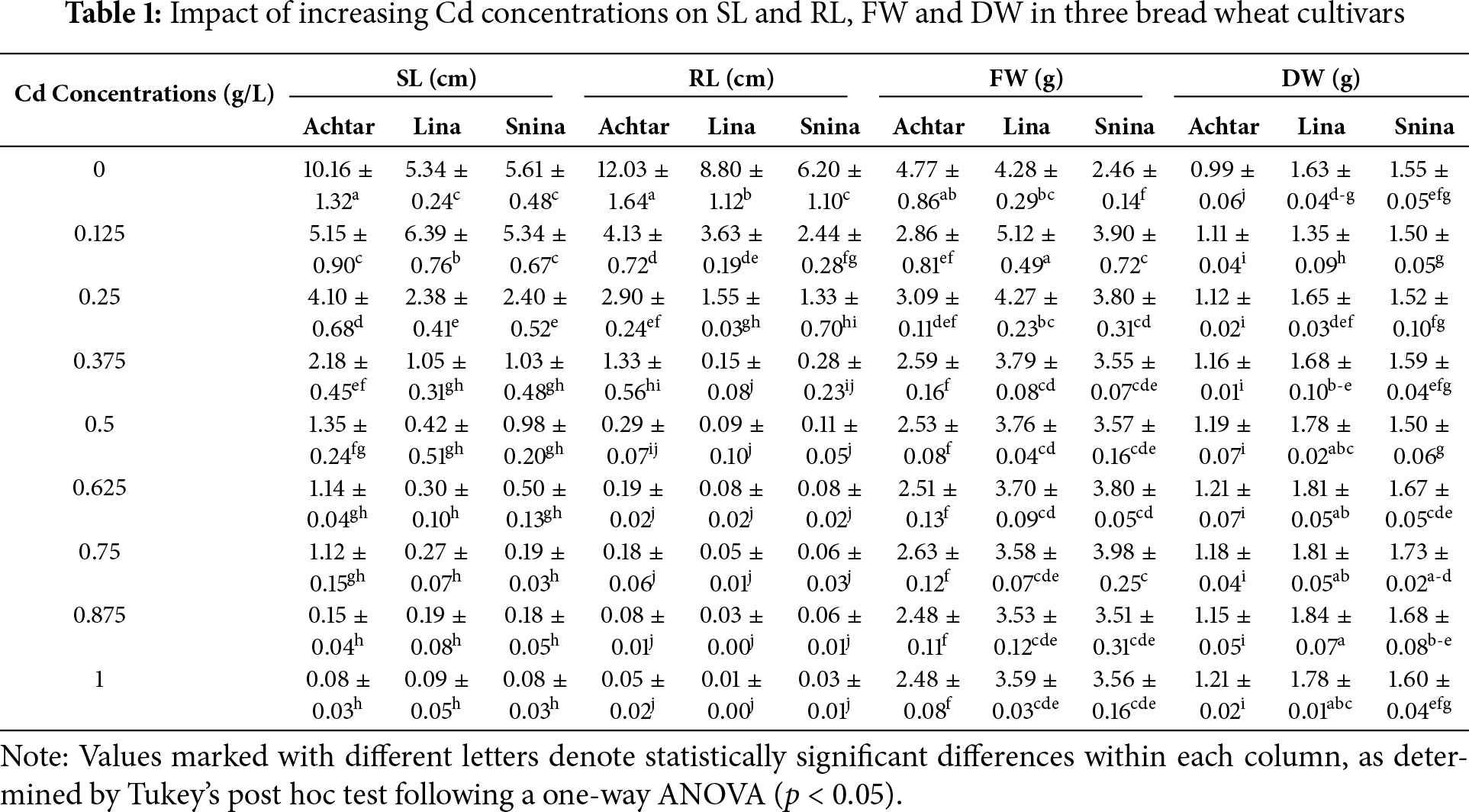

Cd stress led to a progressive and pronounced reduction in shoot length (SL) across all three bread wheat cultivars (Table 1). Under control conditions, Achtar showed the most vigorous shoot development (10.16 cm), while Lina and Snina had shorter shoots (around 5.34–5.61 cm). At 0.125 g/L, Achtar’s SL was significantly reduced by nearly 50% (p < 0.05), whereas Lina exhibited a statistically significant increase compared to the control. From 0.25 g/L onward, all cultivars experienced a sharp decline in SL. Lina and Snina dropped below 2.5 cm by 0.25 g/L, and by 0.5 g/L, Lina’s SL fell drastically to 0.42 cm, significantly lower than Achtar (1.35 cm) and Snina (0.98 cm) (p < 0.05). At the highest Cd levels (0.875–1 g/L), shoot growth was almost completely arrested in all cultivars (below 0.1 cm). Despite this, Achtar consistently maintained higher SL than Lina and Snina across treatments except the highest.

Root length (RL) was even more severely affected by Cd than SL, with early and sharp reductions observed as Cd levels increased (Table 1). In the absence of stress (0 g/L), Achtar displayed the most developed roots, followed by Lina and Snina. A significant decline (p < 0.05) occurred at 0.125 g/L in all cultivars, with reductions exceeding 65% compared to the control. RL continued to decrease rapidly across concentrations, especially from 0.25 to 0.5 g/L, where Lina and Snina dropped below 0.12 cm. At 1 g/L, Lina’s RL reached the lowest recorded value (0.01 cm), while Achtar consistently retained higher RL than the others at all concentrations. ANOVA confirmed significant differences between cultivars and treatments (p < 0.05).

Cd exposure affected both fresh weight (FW) and dry weight (DW) accumulation, with significant changes (p < 0.05) observed at specific concentrations (Table 1). In Achtar, FW significantly dropped from control to 1 g/L (p < 0.05), while DW remained largely unaffected. Lina exhibited significant increases in both FW and DW at low Cd concentrations (0.125–0.375 g/L) (p < 0.05), then plateaued. In Snina, DW peaked at 0.75 g/L, showing a significant increase compared to the control (p < 0.05), whereas FW changes were minimal.

2.3 Impact of Cd on Wheat Tolerance Indices

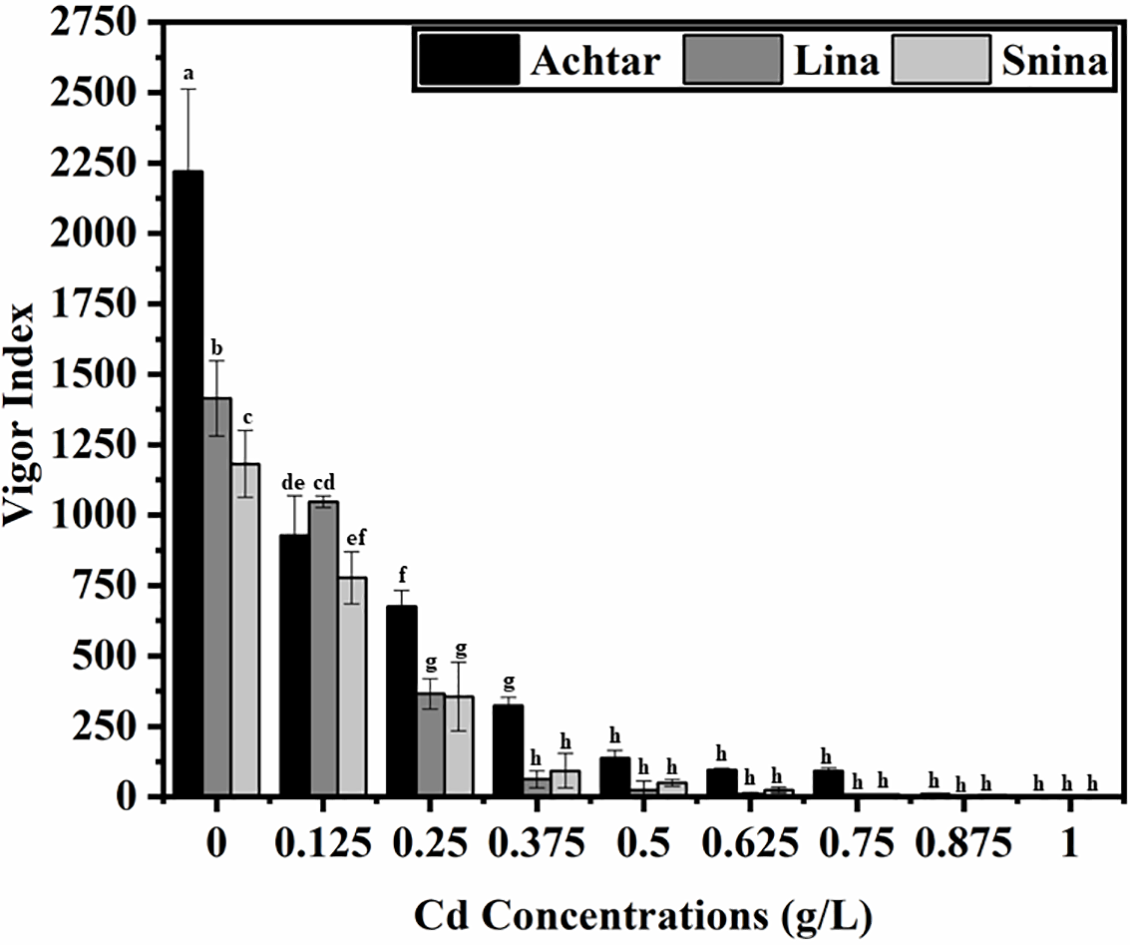

Cd exposure led to a substantial and progressive decline in vigor index (VI) across all three wheat cultivars, indicating a strong suppressive effect on seedling performance under stress (Fig. 2). Under control conditions (0 g/L Cd), Achtar exhibited the highest VI (2219.83), followed by Lina (1414.00) and Snina (1181.50) with statistically significant differences between cultivars (p < 0.05). At 0.125 g/L Cd, VI values declined notably to 927.67 (Achtar), 1046.89 (Lina), and 777.33 (Snina), yet remained statistically distinguishable, indicating variability in cultivar responses at this stress level. As the stress intensified to 0.25 g/L, VI further declined to 675.73 (Achtar), 365.27 (Lina), and 355.39 (Snina), with Achtar maintaining a significantly higher VI compared to the others (p < 0.05). Beyond 0.375 g/L, VI values significantly declined across all cultivars compared to the control (p < 0.05). At 0.5 g/L Cd, values fell to 137.00 (Achtar), 62.15 (Lina), and 92.59 (Snina), with statistical differences still evident. At 0.625 g/L, VI dropped below 95 across all cultivars, with no statistically significant differences. At the highest concentrations tested (0.75–1 g/L), VI values became negligible, with all cultivars showing values between 0.57 and 9.8. Although Achtar showed slightly higher VI values at 0.875 and 1 g/L (9.8 and 5.26) compared to Lina (3.41 and 0.56) and Snina (6.88 and 2.63), these differences were no longer statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Figure 2: The impact of Cd on seedling vigor of the three studied wheat varieties. Bars marked with different letters represent statistically significant differences as determined by Tukey’s post hoc test following a one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05)

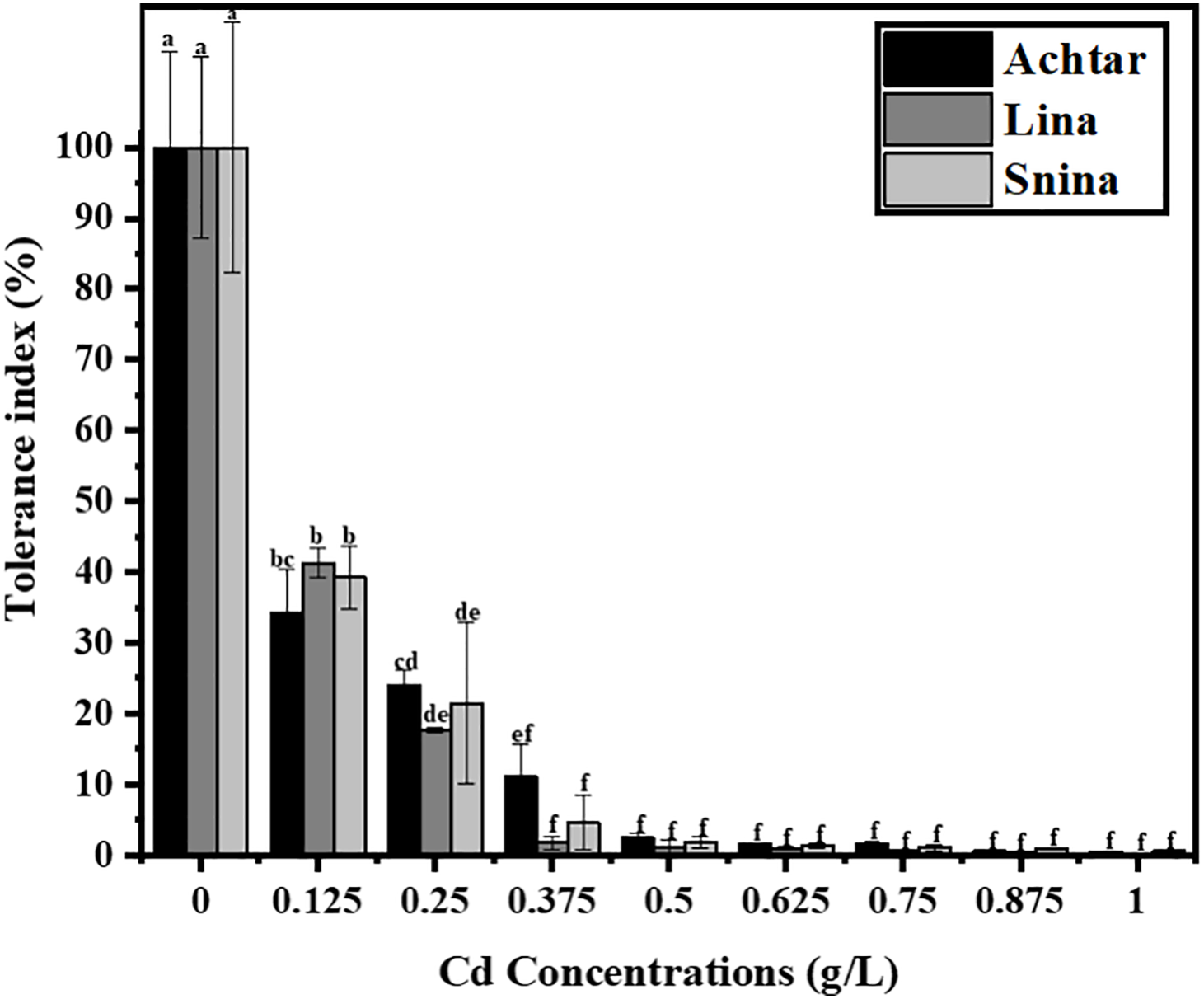

Cd exposure caused a sharp and dose-dependent reduction in Tolerance index (TI) across all three wheat cultivars, with significant intervarietal differences detected from the lowest tested concentration (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3). Under control conditions, TI was set at 100% for all cultivars. At 0.125 g/L, TI significantly decreased by more than 50% (p < 0.05), with Lina recording 41.30%, followed by Snina (39.30%) and Achtar (34.29%). As Cd levels increased, TI values dropped rapidly. At 0.25 g/L, Achtar recorded a higher TI (24.07%), compared to Snina (21.45%) and Lina (17.67%), with differences being statistically significant (p < 0.05). From 0.375 g/L onward, all cultivars exhibited marked declines in TI, falling below 12%. At 0.5 g/L, Achtar retained 2.40%, while Lina and Snina dropped below 2%. By 0.75 g/L, Lina fell below 1%, whereas Achtar and Snina retained 1.53% and 1.04%, respectively. At 1 g/L, all cultivars showed near-total inhibition, with TI values under 0.6%.

Figure 3: The impact of Cd on wheat tolerance of the three studied wheat varieties. Bars marked with different letters represent statistically significant differences as determined by Tukey’s post hoc test following a one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05)

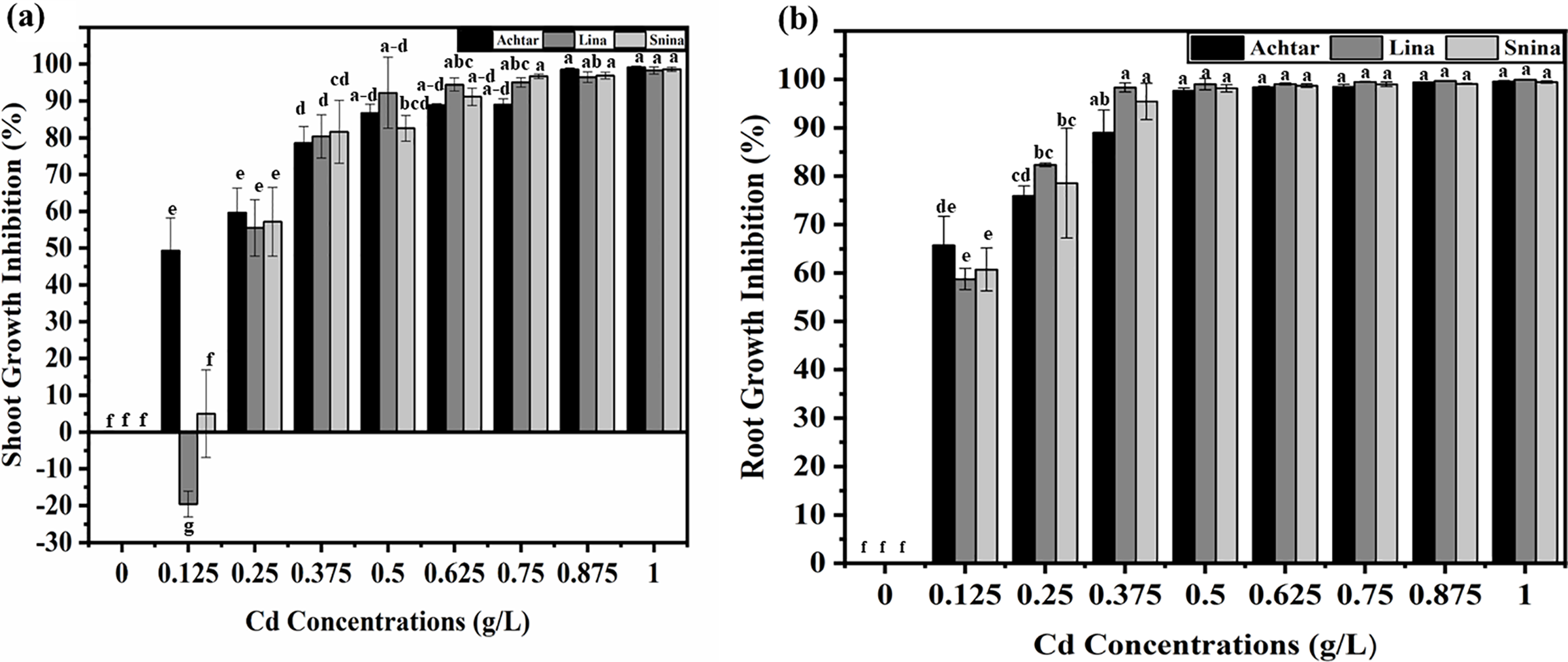

Analysis of shoot growth inhibition (GIS) revealed a clear concentration-dependent response to Cd exposure, with differences becoming statistically significant at even low doses (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4a). At 0.125 g/L, Achtar exhibited 49.3% inhibition, while Lina showed a stimulation effect (−19.56%), and Snina remained near the baseline (4.96%). From 0.25 g/L onward, GIS increased across all cultivars. At 0.375 g/L, inhibition reached to 78.6% in Achtar, 80.4% in Lina, and 81.7% in Snina, with significant differences among cultivars (p < 0.05). At higher concentrations ≥0.5 g/L, GIS exceeded 85% in all cultivars and approached complete inhibition at 1 g/L, with values of 99.16% in Achtar, 98.22% in Lina, and 98.58% in Snina.

Figure 4: The impact of Cd on wheat shoot and root inhibition of the three studied wheat varieties. (a) Shoot growth inhibition under Cd stress, (b) Root growth inhibition under Cd stress. Bars marked with different letters represent statistically significant differences as determined by Tukey’s post hoc test following a one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05)

Root growth inhibition (GIR) also showed a strong concentration-dependent increase (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4b). At 0.125 g/L, GIR reached 65.7% in Achtar, 60.7% in Lina, and 58.5% in Snina. At 0.25 g/L, GIR exceeded 78% in all cultivars and continued to rise. At 0.375 g/L, Achtar reached 88.96%, Lina 98.31%, and Snina 95.40%. From 0.5 g/L upward, GIR values plateaued near complete inhibition. At 1 g/L, all cultivars showed GIR values above 99%, indicating strong suppression of root elongation.

2.4 Pearson Correlation and PCA

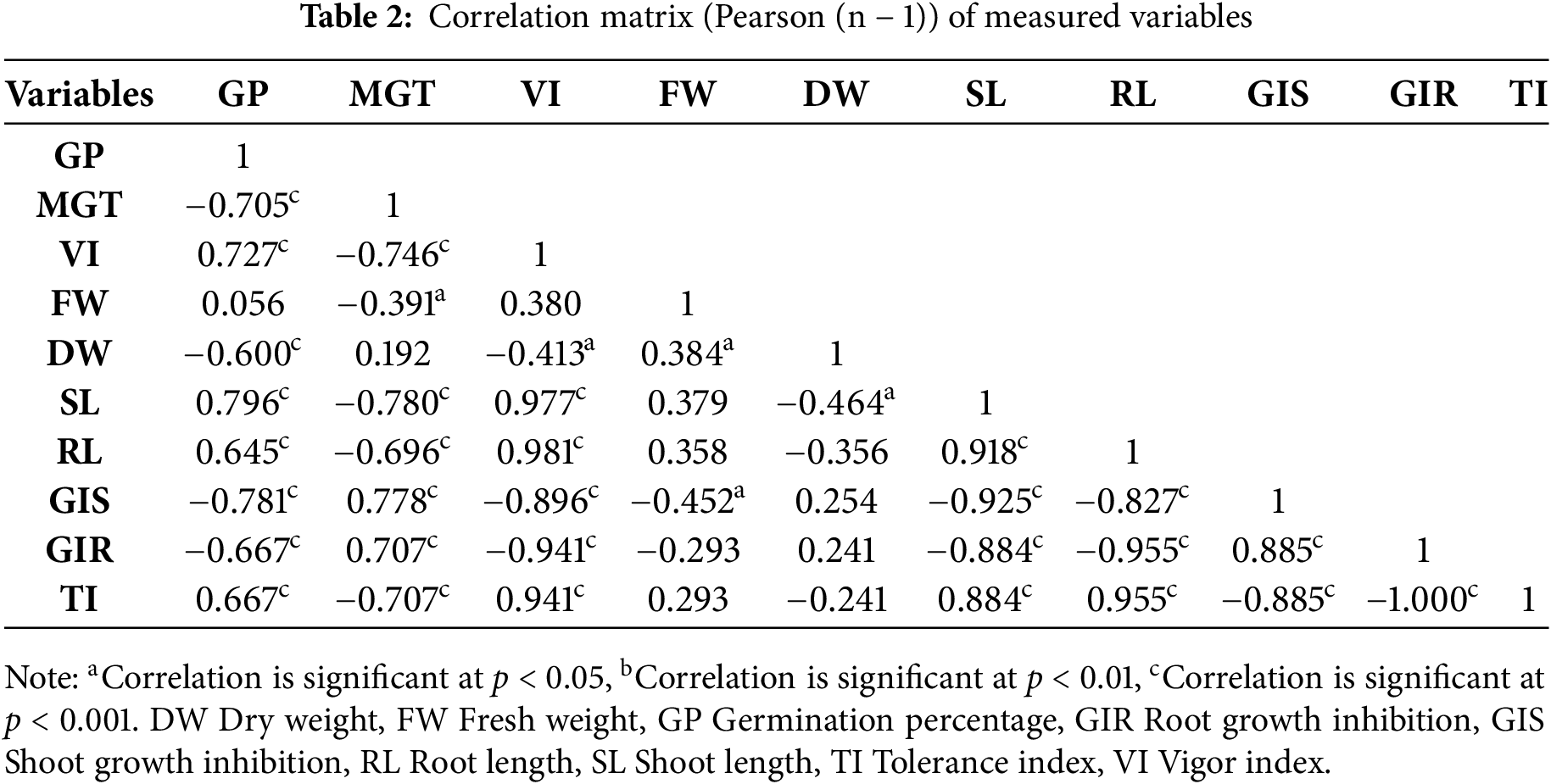

The Pearson correlation analysis revealed several statistically significant associations between germination-related and growth-related traits in bread wheat cultivars exposed to Cd stress (Table 2). GP was positively correlated with SL (r = 0.796, p < 0.001), RL (r = 0.645, p < 0.001), VI (r = 0.727, p < 0.001), and TI (r = 0.667, p < 0.001). Conversely, GP was negatively correlated with GIS (r = −0.781, p < 0.001), GIR (r = −0.667, p < 0.001), and DW (r = −0.600, p < 0.001), while no significant association was found with FW (r = 0.056, p > 0.05). MGT was inversely correlated with GP (r = −0.705, p < 0.001), SL (r = −0.780, p < 0.001), RL (r = −0.696, p < 0.001), VI (r = −0.746, p < 0.001), and TI (r = −0.707, p < 0.001). MGT also showed positive correlations with GIS and GIR (r = 0.778 and r = 0.707, respectively; both p < 0.001), indicating that slower germination duration was statistically associated with greater inhibition scores. SL and RL exhibited a strong positive correlation (r = 0.918, p < 0.001), and both were highly correlated with VI (r = 0.977 and r = 0.981, respectively; p < 0.001), TI (r = 0.884 and r = 0.955; p < 0.001), and negatively correlated with GIS and GIR (shoot: r = −0.925 and r = −0.884; root: r = −0.827 and r = −0.955; all p < 0.001). VI showed a strong positive correlation with TI (r = 0.941, p < 0.001), and strong negative correlations with GIS and GIR (r = −0.896 and r = −0.941, respectively; p < 0.001). TI showed a strong negative correlation with GIR (r = −1.000, p < 0.001) and with GIS (r = −0.885, p < 0.001). GIS and GIR were positively correlated (r = 0.885, p < 0.001), reflecting a shared pattern of inhibition in shoot and root growth. FW and DW were weakly associated with other variables. FW showed a modest correlation with DW (r = 0.384, p < 0.05), but no significant correlation with GP, SL, or RL, indicating limited association under the tested conditions.

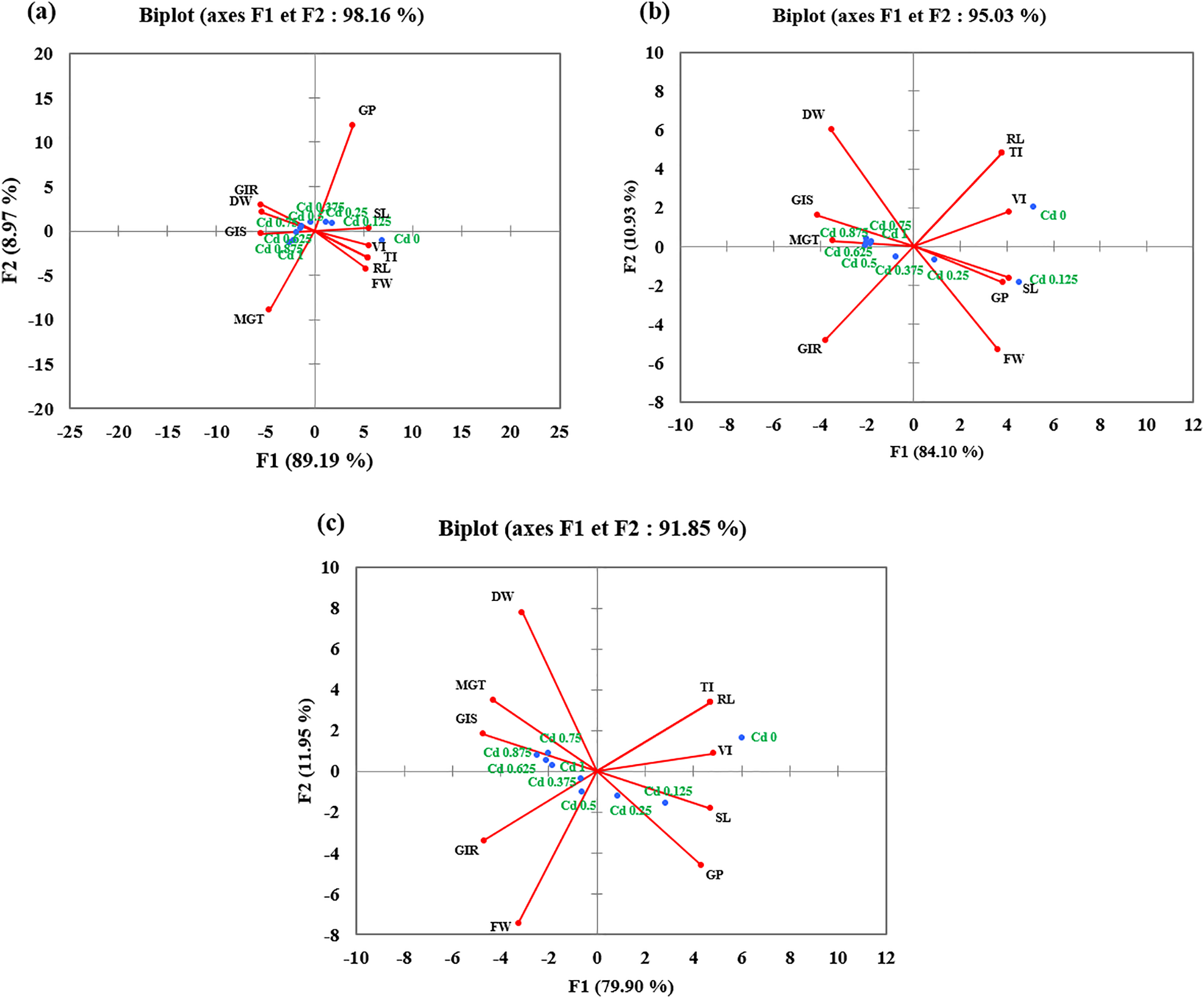

Principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted separately for each cultivar to explore the relationships among germination and growth parameters under Cd stress. The first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) explained the majority of the total variance of 98.16% in Achtar (a), 95.03% in Lina (b), and 91.85% in Snina (c) (Fig. 5). In the biplots, control and low Cd concentrations (0 to 0.25 g/L) were clustered on the positive side of PC1, and positively associated with GP, RL, SL, VI, and in some cases FW (Achtar and Lina). Higher Cd concentrations (≥0.5 g/L) were positioned on the negative side of PC1, correlating strongly with MGT, GIS, GIR, and DW. This distribution along PC1 reflects the separation between traits linked to low stress and those affected by higher Cd exposure. PC2 contributed modestly to variance and helped distinguish biomass traits, particularly in Lina and Snina.

Figure 5: Principal component analysis of germination and growth traits in three wheat cultivars under varying Cd concentrations. (a) Achtar, (b) Lina, and (c) Snina. DW: Dry weight; FW: Fresh weight; GP: Germination percentage; GIR: Root growth inhibition; GIS: Shoot growth inhibition; RL: Root length; SL: Shoot length; TI: Tolerance index; VI: Vigor index

Seed germination marks the transition of a dormant seed into an active seedling and is initiated by water uptake, triggering metabolic reactivation and culminating in radicle protrusion through the seed coat. This developmental phase is essential for plant establishment and subsequent crop productivity [27,28]. However, environmental contaminants such as heavy metals can profoundly hinder this process [29]. Cd, a non-essential and highly toxic heavy metal, is absorbed unintentionally by plants and severely disturbs physiological homeostasis, including nutrient balance and enzymatic activity [30]. In addition to its inhibitory effects on early growth, Cd’s accumulation in edible plant parts, such as grains, poses a serious risk to food safety and public health, further emphasizing the urgency of identifying tolerant wheat genotypes [31]. In light of growing concerns regarding soil Cd contamination, our study investigated the germination and seedling responses of three bread wheat cultivars (Achtar, Lina, and Snina) exposed to increasing Cd concentrations (0.125 to 1 g/L). A clear inhibitory effect on germination was observed in response to increasing Cd concentrations, as evidenced by a marked decline in GP across all tested cultivars at elevated Cd levels. Cd exposure also led to a noticeable delay in MGT, particularly in the sensitive cultivar Lina. This delay suggests that Cd interferes not only with the onset of germination but also with its temporal regulation. This suppression and delay is consistent with Cd’s recognized phytotoxic properties, which interfere with water absorption and disrupt key enzymatic processes essential for reserve mobilization needed for seed germination [14,32–34]. Notably, high Cd levels can inhibit sugar hydrolysis and its transport from the endosperm to the embryonic axis, possibly due to Cd’s antagonistic effect on enzymes like acid phosphatases and α-amylases, resulting in nutrient deprivation of the growing embryo [1,25]. Cd exposure also appears to interfere with protein metabolism, modify protein profiles, and limit root respiration, leading to accumulation of toxic compounds and hindered cellular activity [30,35]. These physiological disruptions at the biochemical level manifest visibly in early seedling development, as reflected in the reduction of shoot and root growth parameters. SL, a key marker of early vegetative development, was notably reduced under Cd exposure, particularly in the cultivar Lina. This decline may result from Cd-induced oxidative stress or disruption in hormonal signaling pathways that regulate cell elongation and division in shoot tissues [36]. Interestingly, however, Lina showed a slight but statistically significant increase in SL at 0.125 g/L, which may reflect a hormetic response, a phenomenon where low levels of a stressor temporarily stimulate growth before higher levels exert toxic effects [37]. Similarly, RL, which is highly sensitive to external stressors due to its direct contact with the toxic medium, exhibited a more pronounced inhibition than SL [38]. This severe suppression, again most evident in Lina, likely reflects Cd’s interference with root meristem activity, cell wall structure, and mitotic processes [25,39]. The greater sensitivity of roots highlights their role as primary indicators of Cd phytotoxicity during early seedling development [40,41]. The extent of RL inhibition varied among cultivars, with Achtar being the least affected and Lina the most, following the order Achtar < Snina < Lina; a similar trend was observed for SL, albeit with a lower magnitude of inhibition. The growth inhibition observed at the organ level was further supported by the decline in composite indices such as the VI and TI. VI, which reflects the overall physiological strength of seedlings by combining GP with total seedling length, decreased significantly under Cd stress in all cultivars. This reduction captures the cumulative impact of both impaired germination and restricted elongation [12]. TI, which compares seedling length under stress to that in control conditions, also declined sharply, indicating the cultivars’ limited capacity to maintain growth in the presence of Cd [40]. These indices, by integrating physiological and growth responses under stress, offer useful tools for early-stage screening and selection of Cd-tolerant genotypes in breeding programs [42]. This pattern was clearly reflected in our findings, where Achtar consistently showed higher VI and TI values compared to Snina and Lina, supporting its classification as the most tolerant cultivar. These consistent differences across multiple traits suggest that the observed responses to Cd are not merely phenotypic but are likely rooted in genotypic variation [10,43]. Achtar’s superior performance may be linked to lower Cd uptake, more efficient compartmentalization, or stronger antioxidant defenses, such as enhanced activity of ROS-scavenging enzymes (e.g., CAT, APX), as reported in other studies on tolerant bread wheat genotypes [44–46]. PCA confirmed cultivar differentiation under Cd stress, with Achtar grouping closely with favorable traits (GP, RL, SL, VI, TI), and Lina clustering with inhibitory traits (GIS, GIR), highlighting contrasting tolerance levels. Snina showed an intermediate pattern. While these multivariate results support genotype-specific responses, the overall range of tolerance remained relatively narrow, and future studies may benefit from including more genetically contrasting genotypes to better dissect tolerance mechanisms. When comparing the current results with our previous findings on durum wheat subjected to similar Cd treatments, both bread and durum genotypes displayed dose-dependent growth suppression. However, bread wheat, particularly Lina, demonstrated more pronounced declines compared to durum wheat Louiza, especially in root metrics [26]. This difference may result from species-specific physiological traits, such as higher root lignification and slower Cd translocation in durum wheat compared to bread wheat, as well as cultivar-level variation in stress sensitivity [47]. These observed differences likely reflect underlying genotypic variation in Cd uptake, sequestration, and detoxification mechanisms [48], emphasizing the importance of genotype selection in breeding wheat lines with improved tolerance to heavy metal stress [10]. While our study focused on early phenotypic and physiological indicators of Cd stress tolerance, recent integrative studies have highlighted the value of combining transcriptomic and metabolomic approaches to gain deeper mechanistic insights. For instance, Wang et al. [49] demonstrated that manganese sulfate mitigates Cd toxicity in wheat by regulating transporter gene expression, enhancing cell wall reinforcement, and modulating metabolite profiles related to antioxidant defenses. Such multi-level analyses could, in future studies, complement phenotypic screening and further clarify the molecular basis of observed genotype differences in Cd tolerance. This knowledge can support Morocco’s wheat improvement programs, especially in Cd-contaminated areas, by promoting the use of tolerant cultivars like Achtar in screening efforts and contaminated-soil management strategies.

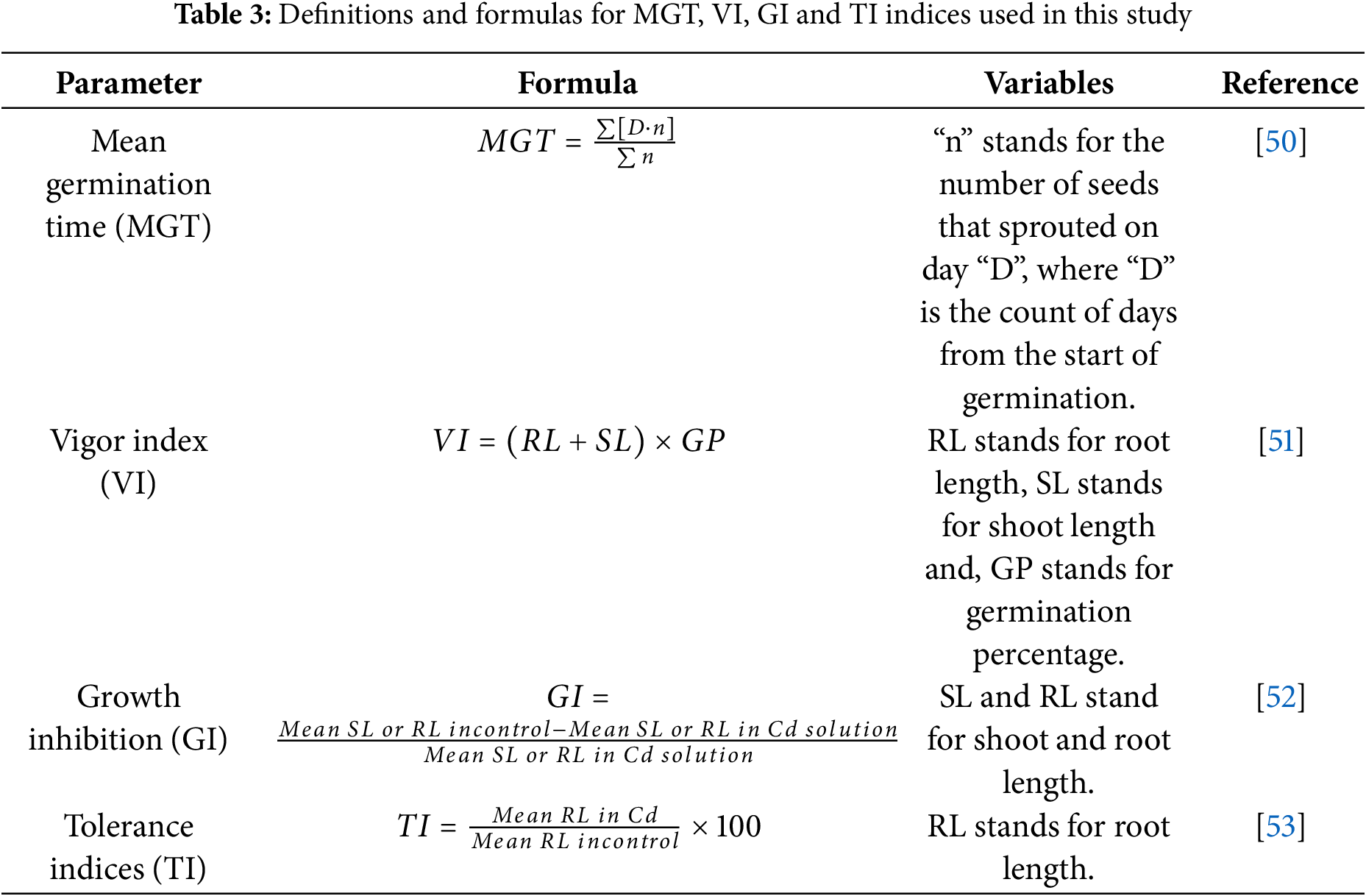

The seeds of the three cultivars of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L. cv. Achtar, cv. Lina, cv. Snina) were obtained from the National Institute for Agronomic Research (INRA), Rabat, Morocco. They are certified cultivars and represent commonly grown wheat varieties in Morocco, known for their adaptation to local agro-climatic conditions and frequently used in regional cultivation trials and research. All experiments were carried out in the laboratory of Biochemistry, Environment, and Agri-food, at the faculty of Science and Techniques of Mohammedia, Morocco. The methodology was adapted from our previous work on Cd stress in durum wheat [26] to ensure for consistency in experimental design while focusing here on bread wheat varieties. This study aimed to evaluate the effects of increasing Cd levels (0, 0.125, 0.25, 0.375, 0.5, 0.625, 0.75, 0.875, 1 g/L) on germination, seedling biomass, and shoot and root elongation. Cd treatments were prepared by dissolving Cd chloride monohydrate (CdCl2, H2O) in ultrapure water, and the pH of each solution was adjusted to 5.5 using nitric acid (HNO3). Wheat seeds exhibiting uniform size and appearance were surface-sterilized by immersion in 5% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite solution for 10 min, followed by multiple rinses with distilled water to remove residual sterilant. For each treatment and cultivar, three Petri dishes were prepared as replicates, with 40 seeds placed in each dish, totaling 120 seeds per treatment per cultivar. Dishes were lined with two layers of filter paper to ensure adequate moisture retention. The control group received 6 mL of sterilized distilled water, while treated groups were irrigated with the same volume of Cd solution. All dishes were maintained in complete darkness at a controlled temperature of 25 ± 2°C. The experimental setup followed a factorial arrangement in a in a completely randomized design with three replicates per condition. After seven days of incubation, the number of germinated seeds was assessed. Following the incubation period, seedling shoot and root lengths were measured using a ruler, taking the main SL and average axial root size. Seedling samples were weighed for FW, and DW was determined after a 48-h oven drying at 70°C. To further evaluate the physiological response of the seedlings to Cd exposure, several growth indices were calculated, including MGT, VI, growth inhibition (GI), and TI, using the formulas presented in Table 3.

Statistical analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics. Data presented are mean values based on three biological repeats ± standard deviation (SD) per treatment. Treatment effects were evaluated through one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and differences among means were identified using Tukey’s post hoc test at a significance threshold of p < 0.05. To further interpret the relationships between measured variables, Pearson’s correlation analysis (n − 1) and PCA were conducted using XLSTAT (version 2016). While the correlation analysis assessed pairwise associations, PCA was used to reduce dimensionality and highlight patterns across treatments and cultivars.

This study demonstrates that Cd exposure significantly hampers wheat germination and early seedling development in a concentration-dependent manner. Key parameters such as GP, SL and RL, and VI were notably affected, with root growth showing higher sensitivity. Differences among cultivars were evident, with Lina being the most sensitive and Achtar the most tolerant. These findings reflect the disruptive effects of Cd on nutrient mobilization, enzyme activity, and cellular development. Correlation analysis and PCA supported these results by revealing consistent interrelations among traits and cultivar-specific responses. Collectively, these results underscore the importance of varietal screening in identifying Cd-tolerant wheat genotypes, which is vital for sustaining wheat production on contaminated soils. Future studies should explore the molecular and biochemical mechanisms underlying these differences to support breeding programs aimed at improving heavy metal tolerance in wheat.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Nada Zaari Jabri, Mohamed Ait-El-Mokhtar, Ghizlane Diria and Abdelaziz Hmyene; methodology, Nada Zaari Jabri, Fadoua Mekkaoui, Mohamed Ait-El-Mokhtar and Abdelaziz Hmyene; software, Mohamed Ait-El-Mokhtar and Nada Zaari Jabri; validation, Nada Zaari Jabri, Mohamed Ait-El-Mokhtar, Abdelaziz Hmyene, Fadoua Mekkaoui, Najwa Rabah, Ghizlane Diria and Ilham Amghar; formal analysis, Mohamed Ait-El-Mokhtar and Nada Zaari Jabri; investigation, Nada Zaari Jabri; resources, Abdelaziz Hmyene, Mohamed Ait-El-Mokhtar and Ghizlane Diria; data curation, Nada Zaari Jabri; writing—original draft preparation, Nada Zaari Jabri; writing—review and editing, Nada Zaari Jabri and Mohamed Ait-El-Mokhtar; visualization, Nada Zaari Jabri; supervision, Abdelaziz Hmyene and Mohamed Ait-El-Mokhtar; project administration, Nada Zaari Jabri. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| ABCC | ATP-Binding Cassette Subfamily C |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| APX | Ascorbate Peroxidase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| Cd | Cadmium |

| DW | Dry weight |

| FW | Fresh weight |

| GI | Growth inhibition |

| GIR | Root growth inhibition |

| GIS | Shoot growth inhibition |

| GP | Germination percentage |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| HMA | Heavy Metal ATPase |

| INRA | National Institute of Agronomic Research |

| MGT | Mean germination time |

| NRAMP | Natural Resistance-Associated Macrophage Protein |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PC1/PC2 | Principal component 1/2 |

| RL | Root length |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SL | Shoot length |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| TI | Tolerance Index |

| VI | Vigor Index |

References

1. Haider FU, Cai L, Coulter JA, Cheema SA, Jun W, Zhang R, et al. Cadmium toxicity in plants: impacts and remediation strategies. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021;211(193):111887. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111887. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Wang M, Chen S, Wang D, Chen L. Agronomic management for cadmium stress mitigation. In: Cadmium tolerance in plants. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2019. p. 69–112. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-815794-7.00003-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Yasmeen T, Li A, Iqbal S, Arif MS, Riaz M, Shahzad SM, et al. Biotechnological tools in the remediation of cadmium toxicity. In: Cadmium tolerance in plants. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2019. p. 497–520. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-815794-7.00018-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Othman YA, Al-Assaf A, Tadros MJ, Albalawneh A. Heavy metals and microbes accumulation in soil and food crops irrigated with wastewater and the potential human health risk: a metadata analysis. Water. 2021;13(23):3405. doi:10.3390/w13233405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zaakour F, Kholaiq M, Khouchlaa A, El Mjiri I, Rahimi A, Saber N. Heavy metal contamination in agricultural soils: a case study in mohammedia benslimane region (Morocco). J Ecol Eng. 2022;23(5):146409. doi:10.12911/22998993/146409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Sanad H, Moussadek R, Mouhir L, Lhaj MO, Zahidi K, Dakak H, et al. Ecological and human health hazards evaluation of toxic metal contamination in agricultural lands using multi-index and geostatistical techniques across the mnasra area of Morocco’s gharb plain region. J Hazard Mater Adv. 2025;18:100724. doi:10.1016/j.hazadv.2025.100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Rao MJ, Duan M, Ikram M, Zheng B. ROS regulation and antioxidant responses in plants under air pollution: molecular signaling, metabolic adaptation, and biotechnological solutions. Antioxidants. 2025;14(8):907. doi:10.3390/antiox14080907. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Faizan M, Alam P, Hussain A, Karabulut F, Tonny SH, Cheng SH, et al. Phytochelatins: key regulator against heavy metal toxicity in plants. Plant Stress. 2024;11(11):100355. doi:10.1016/j.stress.2024.100355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Yue Z, Liu Y, Zheng L, Zhang Q, Wang Y, Hao Y, et al. Integrated transcriptomics, metabolomics and physiological analyses reveal differential response mechanisms of wheat to cadmium and/or salinity stress. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1378226. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1378226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Mourad AMI, Baghdady S, Abdel-Aleem FAM, Jazeri RM, Börner A. Novel genomic regions and gene models controlling copper and cadmium stress tolerance in wheat seedlings. Agronomy. 2024;14(12):2876. doi:10.3390/agronomy14122876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Murtaza G, Hassan NE, Usman M, Deng G, Ahmed Z, Ali B, et al. MXene-nanoparticles foliar application improves wheat morpho-physiological and biochemical traits under cadmium (Cd2+) stress: a novel sustainable approach. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2025;303(5):118781. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2025.118781. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Carvalho MEA, Agathokleous E, Nogueira ML, Brunetto G, Brown PH, Azevedo RA. Neutral-to-positive cadmium effects on germination and seedling vigor, with and without seed priming. J Hazard Mater. 2023;448:130813. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.130813. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. de Fátima Souza Guilherme M, Oliveira HM, Da Silva E. Cadmium toxicity on seed germination and seedling growth of wheat Triticum aestivum L. Acta Sci Biol Sci. 2015;37(4):499. doi:10.4025/actascibiolsci.v37i4.28148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang L, Gao B. Effect of isosteviol on wheat seed germination and seedling growth under cadmium stress. Plants. 2021;10(9):1779. doi:10.3390/plants10091779. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Lamhamdi M, Gharbi S, El Arras M, El Galiou O, El Moudden H, Lee LH, et al. Potential use of Ecdysone in protecting wheat (Triticum aestivum) germination under cadmium stress. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2025;63(4):103479. doi:10.1016/j.bcab.2024.103479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Shedeed ZA, Farahat EA. Alleviating the toxic effects of Cd and Co on the seed germination and seedling biochemistry of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) using Azolla pinnata. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2023;30(30):76192–203. doi:10.1007/s11356-023-27566-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Çatav ŞS, Genç TO, Oktay MK, Küçükakyüz K. Cadmium toxicity in wheat: impacts on element contents, antioxidant enzyme activities, oxidative stress, and genotoxicity. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 2020;104(1):71–7. doi:10.1007/s00128-019-02745-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Mao H, Jiang C, Tang C, Nie X, Du L, Liu Y, et al. Wheat adaptation to environmental stresses under climate change: molecular basis and genetic improvement. Mol Plant. 2023;16(10):1564–89. doi:10.1016/j.molp.2023.09.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Vassileva V, Georgieva M, Zehirov G, Dimitrova A. Exploring the genotype-dependent toolbox of wheat under drought stress. Agriculture. 2023;13(9):1823. doi:10.3390/agriculture13091823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Hammani O, El-Otmani N, Ben Lenda O, El Azhari H, Rfaki A, Lahlouhi N, et al. Exploratory analysis of potential toxic elements in Moroccan couscous and health risk evaluation utilizing ICP-OES. J Trace Elem Miner. 2025;11(5):100207. doi:10.1016/j.jtemin.2024.100207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Abdullahi N, Dandago MA, Gambo MS, Idah PG, Tsoho AU, Rilwan A. Heavy metals uptake pattern and accumulation in wheat. Mor J Agri Sci. 2023;4(4):143–7. doi:10.5281/zenodo.10402080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Elbagory M, Zayed A, El-Khateeb N, El-Nahrawy S, Omara AE, Mohamed I, et al. Risk assessment of potentially toxic heavy metals in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) grown in soils irrigated with paper mill effluent. Toxics. 2025;13(6):497. doi:10.3390/toxics13060497. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Zulfiqar U, Jiang W, Wang X, Hussain S, Ahmad M, Maqsood MF, et al. Cadmium phytotoxicity, tolerance, and advanced remediation approaches in agricultural soils; a comprehensive review. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:773815. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.773815. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Han Z, Osman R, Liu Y, Wei Z, Wang L, Xu M. Analyzing the impacts of cadmium alone and in co-existence with polypropylene microplastics on wheat growth. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1240472. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1240472. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Zulfiqar U, Ayub A, Hussain S, Ahmad Waraich E, El-Esawi MA, Ishfaq M, et al. Cadmium toxicity in plants: recent progress on morpho-physiological effects and remediation strategies. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2022;22(1):212–69. doi:10.1007/s42729-021-00645-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zaari Jabri N, Ait-El-Mokhtar M, Mekkaoui F, Amghar I, Achemrk O, Diria G, et al. Impacts of cadmium toxicity on seed germination and seedling growth of Triticum durum cultivars. Cereal Res Commun. 2024;52(4):1399–409. doi:10.1007/s42976-023-00467-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Carrera-Castaño G, Calleja-Cabrera J, Pernas M, Gómez L, Oñate-Sánchez L. An updated overview on the regulation of seed germination. Plants. 2020;9(6):703. doi:10.3390/plants9060703. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Peng C, Wu Y, Shi F, Shen Y. Review of the current research progress of seed germination inhibitors. Horticulturae. 2023;9(4):462. doi:10.3390/horticulturae9040462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. ErtekiN EN, ErtekiN İ, BiLgen M. Effects of some heavy metals on germination and seedling growth of sorghum. KSU J Agric Nat. 2020;23(6):1608–15. doi:10.18016/ksutarimdoga.v23i54846.722592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Huybrechts M, Cuypers A, Deckers J, Iven V, Vandionant S, Jozefczak M, et al. Cadmium and plant development: an agony from seed to seed. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(16):3971. doi:10.3390/ijms20163971. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Rezapour S, Atashpaz B, Moghaddam SS, Kalavrouziotis IK, Damalas CA. Cadmium accumulation, translocation factor, and health risk potential in a wastewater-irrigated soil-wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) system. Chemosphere. 2019;231:579–87. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.05.095. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Adrees M, Ali S, Rizwan M, Ibrahim M, Abbas F, Farid M, et al. The effect of excess copper on growth and physiology of important food crops: a review. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2015;22(11):8148–62. doi:10.1007/s11356-015-4496-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Du L, Wu D, Yang X, Xu L, Tian X, Li Y, et al. Joint toxicity of cadmium (II) and microplastic leachates on wheat seed germination and seedling growth. Environ Geochem Health. 2024;46(5):166. doi:10.1007/s10653-024-01942-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Faraji J, Sepehri A. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles and sodium nitroprusside alleviate the adverse effects of cadmium stress on germination and seedling growth of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Univ Sci. 2018;23(1):61. doi:10.11144/javeriana.sc23-1.tdna. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Basak P. A critical review on the effect and toxicity of Cadmium mediated stress in plants. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2023;14(11):5087–97. doi:10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.14(11).5087-97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Vijayaragavan M, Prabhahar C, Sureshkumar J, Natarajan A, Vijayarengan P, Sharavanan S. Toxic effect of cadmium on seed germination, growth and biochemical contents of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L.) plants. Int Multidiscip Res J. 2011;1(5):1–6. doi:10.25081/jpsp.2018.v4.3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Agathokleous E, Kitao M, Calabrese EJ. Environmental hormesis and its fundamental biological basis: rewriting the history of toxicology. Environ Res. 2018;165:274–8. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2018.04.034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Yuan HM, Huang X. Inhibition of root meristem growth by cadmium involves nitric oxide-mediated repression of auxin accumulation and signalling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2016;39(1):120–35. doi:10.1111/pce.12597. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Feng Y, Li H, Zhang X, Li X, Zhang J, Shi L, et al. Effects of cadmium stress on root and root border cells of some vegetable species with different types of root meristem. Life. 2022;12(9):1401. doi:10.3390/life12091401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Ahmad I, Akhtar MJ, Zahir ZA, Jamil A. Effect of cadmium on seed germination and seedling growth of four wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivars. Pak J Bot. 2012;44:1569–74. [Google Scholar]

41. Yang Y, Wei X, Lu J, You J, Wang W, Shi R. Lead-induced phytotoxicity mechanism involved in seed germination and seedling growth of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2010;73(8):1982–7. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2010.08.041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Awaad HA, Alzohairy AM, Morsy AM, Moustafa ESA, Mansour E. Genetic analysis of cadmium tolerance and exploring its inheritance nature in bread wheat. Indian J Genet. 2023;83(1):41–51. doi:10.31742/ISGPB.83.1.6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Aprile A, Sabella E, Francia E, Milc J, Ronga D, Pecchioni N, et al. Combined effect of cadmium and lead on durum wheat. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(23):5891. doi:10.3390/ijms20235891. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Guo J, Qin S, Rengel Z, Gao W, Nie Z, Liu H, et al. Cadmium stress increases antioxidant enzyme activities and decreases endogenous hormone concentrations more in Cd-tolerant than Cd-sensitive wheat varieties. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2019;172(7):380–7. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.01.069. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Abdolmalaki Z, Soorni A, Beigi F, Mortazavi M, Najafi F, Mehrabi R, et al. Exploring genotypic variation and gene expression associated to cadmium accumulation in bread wheat. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):26505. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-78425-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Thind S, Hussain I, Ali S, Rasheed R, Ashraf MA. Silicon application modulates growth, physio-chemicals, and antioxidants in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) exposed to different cadmium regimes. Dose Response. 2021;19(2):15593258211014646. doi:10.1177/15593258211014646. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Hart J, Welch R, Norvell W, Sullivan L, Kochian L. Characterization of cadmium binding, uptake, and translocation in intact seedlings of bread and durum wheat cultivars. Plant Physiol. 1998;116(4):1413–20. doi:10.1104/pp.116.4.1413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Noor I, Sohail H, Akhtar MT, Cui J, Lu Z, Mostafa S, et al. From stress to resilience: unraveling the molecular mechanisms of cadmium toxicity, detoxification and tolerance in plants. Sci Total Environ. 2024;954(4):176462. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.176462. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Wang Y, Hou K, Xing W, Shao R, Gao X, Zhang S, et al. Physiological, transcriptomic, and metabolomic integrated analyses reveal key factors involved in manganese sulfate mitigating cadmium toxicity in wheat. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2025;229(A):110313. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2025.110313. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Ellis RH, Roberts EH. Improved equations for the prediction of seed longevity. Ann Bot. 1980;45(1):13–30. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a085797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Baruah N, Mondal SC, Farooq M, Gogoi N. Influence of heavy metals on seed germination and seedling growth of wheat, pea, and tomato. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2019;230(12):273. doi:10.1007/s11270-019-4329-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Ahmad I, Akhtar MJ, Asghar HN, Zahir ZA. Comparative Efficacy of growth media in causing cad-mium toxicity to wheat at seed germination stage. Int J Agric Biol. 2013;15(3):517–22. [Google Scholar]

53. Iqbal MZ, Rahmati K. Tolerance of albizia lebbeck to Cu and Fe application. Ekológia Čsfr. 1992;11(4):427–430. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools