Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Review of Phenolic Compounds: From Biosynthesis and Ecological Roles to Human Health and Nutrition

Department of Agroecology and Environmental Protection, Faculty of Agrobiotechnical Sciences Osijek, Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Vladimira Preloga 1, Osijek, 31000, Croatia

* Corresponding Author: Miroslav Lisjak. Email:

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(11), 3297-3318. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.072504

Received 28 August 2025; Accepted 29 October 2025; Issue published 01 December 2025

Abstract

Phenolic compounds represent a broad and structurally diverse class of plant secondary metabolites with importance for both plant biology and human health. This review provides a comprehensive overview of their biosynthesis, chemical diversity, multifaceted functions in plants, roles in the wider ecosystem, and significance in human nutrition and biotechnology. Primarily synthesized via the phenylpropanoid pathway, these compounds encompass major classes such as lignin, flavonoids, and tannins. Within the plant, they perform critical functions including providing structural support (lignin), defending against biotic stresses (e.g., pathogens, herbivores), mediating ecological interactions (pollination, symbiosis, allelopathy), and protecting against abiotic stresses like UV radiation and oxidative damage. Phenolic compounds extend their influence beyond the plant itself by shaping soil ecosystems through rhizodeposition, where they interact with microbial communities and nutrient cycles. At the same time, they play a central role in the health benefits of plant-rich diets, with strong epidemiological evidence linking their regular consumption to a reduced risk of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, and obesity. The review further examines the significant variation of phenolic content in different food sources and explores the impact of processing methods, highlighting germination as a key strategy for enhancing the nutritional and bioactive value of cereals and legumes. Finally, the potential of phenolic compounds as a source for modern drugs and their targeted production through biotechnological approaches are discussed, underscoring their position as a cornerstone of phytochemical research with ongoing and future applications in health, agriculture, and industry. This paper employs a semi-systematic (or narrative) literature review methodology. A strategic search of key academic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar, was conducted to identify relevant literature and highly influential works. This review aims to synthesize the existing knowledge on phenolic compounds and to emphasize their undeniable impact on human health through an interdisciplinary approach.Keywords

Phenolic compounds are a broad and functionally diverse class of plant secondary metabolites central to both plant biology and human health. Their roles in structural support, defense, and environmental interactions are essential for plant survival, while for humans, they are a cornerstone of the health benefits derived from a plant-rich diet, offering protection against a wide range of chronic diseases [1,2]. A substantial body of epidemiological evidence has associated the regular consumption of diets rich in fruits and vegetables with a reduced risk of major chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease, certain types of cancer, and neurodegenerative disorders [3]. They are primarily known for their potent antioxidant properties, enabling them to scavenge free radicals and mitigate the oxidative stress that underlies many pathological conditions. Furthermore, research has demonstrated their ability to exert important anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and cell-signaling modulatory effects [4]. However, the actual dietary impact of these beneficial compounds is complex and depends on numerous variables. The concentration and profile of phenolics in raw produce are highly inconsistent, varying dramatically due to genetic factors (species and cultivar), environmental conditions, and post-harvest handling [5]. Moreover, food processing significantly alters the final phytochemical profile that is consumed. Cooking, in particular, has a profound effect; while methods like boiling can cause significant losses of water-soluble compounds, other techniques may enhance the bioavailability of certain phenolics by releasing them from the plant matrix [6]. To understand their function, it is important to first consider their origin. The biosynthesis of most plant-derived phenolic compounds occurs via the shikimic acid pathway [7,8]. This pathway draws on intermediates of primary metabolism specifically, phosphoenolpyruvate from glycolysis and erythrose-4-phosphate from the pentose phosphate pathway to synthesize aromatic amino acids. In higher plants, phenylalanine serves as the principal precursor for the majority of phenolic compounds [9]. Although the shikimic acid pathway is central metabolic route in plants, fungi, and bacteria, an alternative, the malonate pathway, also contributes to phenolic biosynthesis, particularly in fungi and bacteria, but plays minor role in plants [7]. Notably, the shikimic acid pathway is absent in animals, which consequently cannot synthesize the essential aromatic amino acids: phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan [10]. The biosynthesis of most secondary phenolics begins with the amino acid phenylalanine [11–13]. The first committed step in this pathway is its deamination to form trans-cinnamic acid, a reaction catalyzed by phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) [14]. PAL is a critical regulatory point, controlled primarily at the level of gene transcription in response to various developmental cues and environmental stimuli, such as pathogen infection, wounding, or light [13]. The product, trans-cinnamic acid, provides the foundational C6-C3 phenylpropanoid structure. From this precursor, several classes of simple phenolics are derived, including direct phenylpropanoids (e.g., caffeic and ferulic acids), phenylpropanoid lactones known as coumarins, and C6-C1 benzoic acid derivatives, which are formed by the shortening of the propanoid side chain [12,14]. Beyond their foundational roles, many phenolic compounds also serve as crucial defensive agents against herbivores and pathogens. A notable example is the furanocoumarins, which are common in the Apiaceae family [15]. These compounds are phototoxic; upon activation by UV-A light (320–400 nm), they intercalate into DNA and form covalent adducts with pyrimidine bases (cytosine and thymine) [16]. This action blocks DNA transcription and repair, potentially leading to cell death. In addition to defense, phenolics are implicated in allelopathy, where they are released from plant tissues and litter into the environment. The phenylpropanoid pathway is a key metabolic route activated under stress conditions, resulting in the increased synthesis of phenolic compounds which serve as a crucial defense mechanism [17–22]. Simple phenolic compounds, such as caffeic and ferulic acid, have been shown to inhibit the germination and growth of competing species under laboratory conditions [16]. However, the ecological significance and definitive impact of allelopathy in natural ecosystems remain a subject of considerable scientific debate [23]. Plant phenolic compounds are a large and diverse class of secondary metabolites involved in a multitude of essential functions, ranging from structural support and defense to pigmentation and signaling [24]. Among these, lignin is praticulary notable. This highly branched polymer of phenylpropanoid units and, after cellulose, the most abundant organic substance in plants [25]. Its complex structure, formed through covalent bonds with cell wall polysaccharides, makes extraction and analysis challenging. Lignin is synthesized via the polymerization of three precursor alcohols: coniferyl, coumaryl, and sinapyl alcohol, catalyzed by peroxidase enzymes [25,26]. These enzymes oxidize monolignols into free-radical intermediates, which then combine non-enzymatically to generate a three-dimensionally branched structure that integrates with cellulose microfibrils in the cell wall [25]. Flavonoids are another ubiquitous and diverse class of plant phenolics, recognized for their characteristic C15 (C6-C3-C6) skeleton derived from the shikimic and acetate biosynthetic pathways. Responsible for much of plant pigmentation, their basic structure is extensively modified by reactions like hydroxylation and glycosylation, which alters their properties and defines subclasses such as flavones, flavonols, and anthocyanins [27]. These compounds perform a wide array of functions. For instance, anthocyanins provide visible pigmentation in flowers and fruits to attract pollinators, while flavones and flavonols create UV patterns visible to insects and shield tissues from UV-B radiation [14]. Specific flavonoids are crucial in mediating legume-rhizobia symbiosis by activating bacterial genes. Others act as defense compounds, such as isoflavonoids that function as antimicrobial phytoalexins or insecticidal rotenoids [10]. They also serve as signals for parasitic plants [28] and as endogenous regulators of polar auxin transport [29]. Furthermore, flavonoids mitigate abiotic stress by scavenging free radicals and chelating toxic metals, a mechanism implicated in aluminum tolerance [30]. Among the defensive compounds, tannins stand out as important plant phenolic polymers. They are classified into two main groups: condensed tannins, which are polymers of flavonoid units common in woody plants, and hydrolyzable tannins, which are polymers of phenolic acids and simple sugars [31]. The primary defensive action of tannins is their ability to bind and precipitate proteins. This property makes them effective toxins against herbivores by inhibiting digestive enzymes and reducing nutrient absorption, thus deterring feeding [32]. While, some herbivores have adapted by producing proline-rich salivary proteins that neutralize tannins, these compounds remain effective deterrents. In addition, tannins protect non-living plant tissues such as wood from microbial decay by inhibiting fungal and bacterial growth [10]. This review will provide an overview of the biosynthesis, biological functions, and ecological significance of phenolic compounds, with particular emphasis on their roles in plant-environment interactions, their importance for agriculture, and their relevance to human health.

2 Biosynthesis, Diversity, and Function of Phenolic Compounds

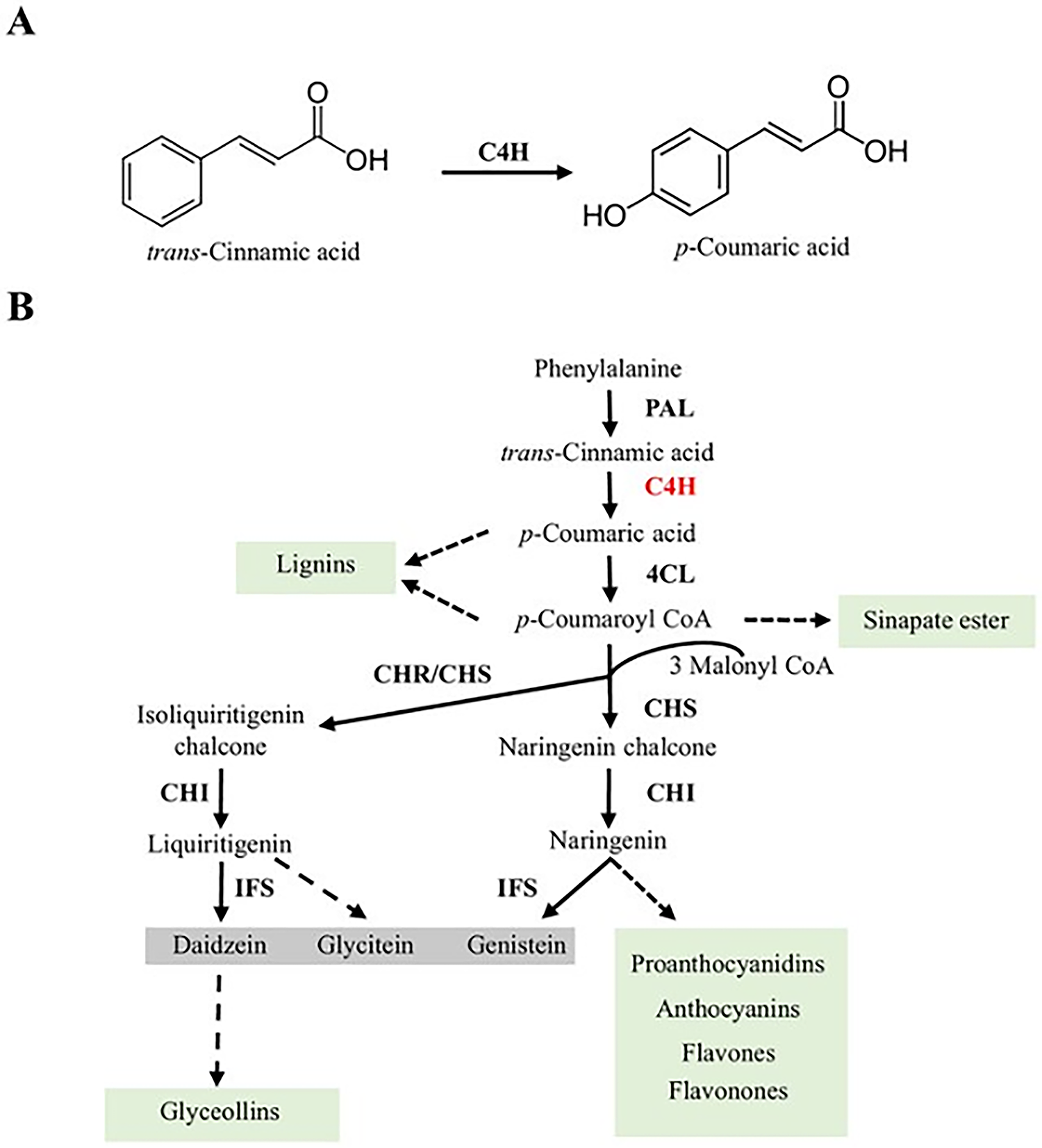

Flavonoids, along with tannins, hydroxycinnamate esters, and lignin, are synthesized via the phenylpropanoid pathway, a central metabolic route in plants [11]. They serve critical functions as UV protectants, defense compounds against pathogens, signaling molecules for plant-microbe interactions, and regulators of reactive oxygen species. The biosynthesis pathway has been validated through the analysis of numerous mutants [29]. The degradation of these aromatic compounds is essential and is performed by plants themselves or, more significantly, by soil microorganisms, with a portion entering aquatic systems [33]. The metabolic turnover of plant phenolics involves three primary fates: interconversion within biosynthetic pathways, catabolism into primary metabolites, and oxidative polymerization into insoluble structures. These pathways operate concurrently, forming a complex metabolic network whose regulation determines the final fate of these compounds [34]. The phenylpropanoid pathway, responsible for producing a diverse range of phenolic metabolites (Fig. 1), recent evidence suggests that this pathway provides an alternative route for photochemical energy dissipation, thereby mitigating the over-production of harmful ROS [17,35–37]. While many key polyphenols such as flavonoids and lignin are derived from the phenylpropanoid pathway, other significant classes, including stilbenes and lignans, have distinct biosynthetic origins and crucial biological functions [38]. Stilbenes, for example, are known for their strong antioxidant and antifungal properties, with resveratrol being a well-studied example found in grapes and berries. Lignans, on the other hand, are diphenolic compounds often found in seeds and whole grains, and are recognized for their potential health benefits [25,39]. From a pharmacognostical perspective, this remarkable chemical diversity translates directly into a wide spectrum of biological activities. Consequently, this vast chemical family includes numerous prominent classes of bioactive substances, such as coumarins, chromones, anthracenes, naphthoquinones, and xanthones, each representing a fertile ground for drug discovery [40]. The phenylpropanoid pathway is a central hub for the synthesis of many phenolic compounds, but it is important to recognize the broader diversity of polyphenols, including those with different core structures. For instance, ellagitannins are a complex class of hydrolyzable tannins found in pomegranates and raspberries, structurally distinct from phenylpropanoid derivatives [32]. The structural variety of these compounds underpins their wide range of biological activities and distribution across the plant kingdom.

Figure 1: Phenylpropanoid biosynthetic pathway. (A) C4H catalyzes the hydroxylation of trans-cinnamic acid at the 4′ position, forming p-coumaric acid. (B) Schematic representation of the soybean phenylpropanoid pathway, highlighting the role of C4H (in red) in the biosynthesis of specialized metabolites, including isoflavones (daidzein, genistein, glycitein), as well as other downstream products (highlighted in green) [40]

2.1 The Role of Phenolic Compounds in Plant-Environment Interactions

The anaerobic degradation of aromatic compounds is not uniform. A study by Schink et al. (2000) demonstrated that the strategy employed by bacteria depends on the organism’s energetic status and the redox potential of available electron acceptors. This is exemplified by the use of different, energy-dependent variants of the benzoyl-CoA pathway by fermenting versus nitrate-reducing bacteria. The phenylpropanoid pathway originates from L-phenylalanine via the enzyme L-phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL). A central three-enzyme sequence (PAL, cinnamate 4-hydroxylase, and 4-coumarate: coenzyme A ligase) produces an activated hydroxycinnamic acid derivative. These include simple C6C3 structures like monolignols, more complex flavonoids and stilbenes (formed by condensation with acetate-derived units), and C6C1 benzoic acids (formed via side-chain shortening) [41]. The distribution of these compounds varies taxonomically. While hydroxycinnamic acids and flavonoids are ubiquitous in higher plants, other classes, such as isoflavonoids and stilbenes, are restricted to specific families like Leguminosae or found sporadically in divergent species [12]. Isoflavonoids, primarily confined to the Papilionoideae (Leguminosae), and stilbenes, which occur sporadically in species such as peanut, grapevine, and pine, represent more specialized branches of the phenylpropanoid family [42,43]. Natural products for plant defense fall into three categories: phytoalexins, phytoanticipins, and signaling molecules. Many phenylpropanoids act as broad-spectrum antimicrobials against pathogens and are classified as either pre-formed phytoanticipins or inducible phytoalexins [24,43,44]. Well-known phenylpropanoid phytoalexins include pterocarpans, isoflavans, and isoflavanones found in legumes such as beans and soybeans. Prenylated isoflavones in lupine, which are synthesized during seedling development, are a good example of phytoanticipins [45]. Ecological stresses such as intense light, low temperatures, pathogen infection, and nutrient deficiency can lead to increased production of free radicals and other oxidatively active substances in plants. A growing body of evidence indicates that plants respond to biotic and abiotic stress factors by increasing their ROS-scavenging capacity [46]. Efforts to understand this process have focused on the components of the classic antioxidant system, i.e., superoxide dismutase, ascorbate peroxidase, catalase, monodehydroascorbate reductase, glutathione reductase, and the low-molecular-weight antioxidants ascorbate and glutathione [47]. In a study by Grace and Logan (2000), leaves from three mahonia populations were collected during summer and winter. The phenylpropanoid pathway creates products that enhance stress tolerance and may also use up excess photons under conditions of carbohydrate accumulation or high light. Chlorogenic acid (CGA), a major product of this pathway, is a powerful antioxidant that helps plants cope with stress. It also recycles orthophosphate and consumes reducing power, which enables photosynthesis to continue and provides further protection from oxidative stress [48]. The overexpression of key enzymes in biosynthetic pathways to achieve overproduction of value-added products typically imposes a metabolic burden on cells. 4CL, a key enzyme catalyzing the formation of CoA thioesters of hydroxycinnamic acids, has therefore become a prime target for metabolic engineering [49]. The biosensor demonstrated good specificity and robustness, enabling the rapid and sensitive selection of resveratrol hyperproducers. A 4CL variant with enhanced activity was selected from a 4CL mutagenesis library constructed in the resveratrol biosynthetic pathway in Escherichia coli. This mutant led to increased production of not only resveratrol but also the flavonoid naringenin when introduced into their respective biosynthetic pathways [50]. The results demonstrated the feasibility of improving the activities of key enzymes in important biosynthetic pathways using engineered biosensors [11]. Although the study of phenylpropanoid bioactivity dates back to the beginning of the last century, the field has remained underexplored. The recently discovered molecular mechanism explaining the activity of c-CA could be a significant step forward [51,52]. By inhibiting auxin transport, c-CA affects the tightly regulated redistribution of auxin in the root meristem. Acropetal auxin transport in the root is unaffected, and the continuous supply of auxin that is not redistributed within the meristem results in its accumulation in the primary root [53].

Recent advances in biotechnology offer powerful solutions to the challenges of producing and standardizing polyphenols. Metabolic engineering and synthetic biology are being used to create microbial “cell factories” such as engineered bacteria and yeast, that can produce high yields of specific polyphenols from simple, inexpensive carbon sources like glucose. This approach overcomes issues with inconsistent plant harvests and low bioavailability from natural sources [54]. For instance, recent research has successfully engineered E. coli to produce pinosylvin, a valuable stilbene, at much higher concentrations than are naturally found [55]. Additionally, advanced gene-editing tools like CRISPR-Cas9 are being applied directly to plants to manipulate their metabolic pathways. In a recent example from 2025, scientists used CRISPR to knock out a key gene in grape cells, effectively redirecting metabolic flux away from flavonoid production and dramatically increasing the yield of the more sought-after polyphenol, resveratrol [56].

2.2 Flavonoids and Phenolic Compounds as Ecological and Biochemical Mediators in Plant–Soil Systems

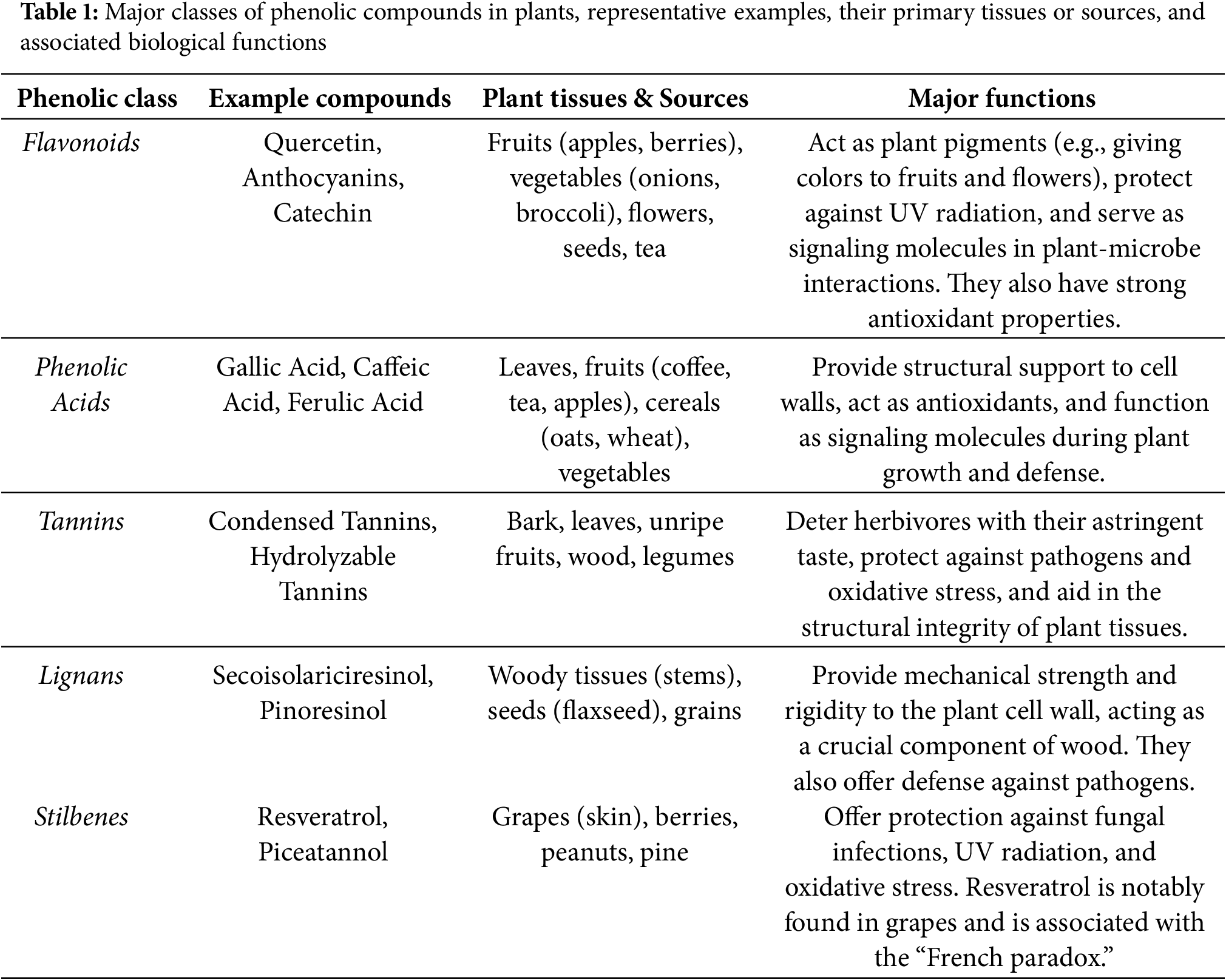

Allelopathy is the biochemical process where a plant releases secondary metabolites (allelochemicals) that influence neighboring organisms [57]. This interaction is not limited to plant-plant competition but forms a complex ecological network affecting insects, fungi, and bacteria [50]. Phenolic compounds, particularly flavonoids, are key mediators in this process, serving as agents for defense and communication. The biosynthesis of these flavonoids begins with chalcone synthase (CHS), which catalyzes the formation of a chalcone. This intermediate is then converted into a flavanone by chalcone isomerase (CHI) [58,59]. The flavanone serves as a central precursor from which the pathway branches to produce the diverse classes of flavonoids [57]. Flavonoids undergo post-synthesis modifications, primarily methylation and glycosylation, which alter their solubility, stability, and biological reactivity; consequently, most flavonoids exist naturally as glycosides [60]. This structural diversity confers a wide range of functions, including protection against biotic and abiotic stresses (e.g., pathogens, UV radiation) and maintenance of cellular redox homeostasis [61]. As shown in Table 1, phenolic compounds play diverse roles in plant physiology. The antioxidant capacity of flavonoids is determined by specific structural features, such as conjugated double-bond systems and the arrangement of functional groups, which enable them to effectively suppress reactive oxygen species (ROS) [28]. Soil is a complex system resulting from the interaction of many factors: climate, soil organisms, substrate, and topography. Soils provide the substrate for nature and agriculture; in both cases, the soil represents an ecosystem [62]. This soil ecosystem is not just a mixture of living and non-living matter but also encompasses the complex interactions of these components [59]. All these processes together potentially enrich the soil with mineral nutrients and redistribute organic matter from plant residues, increasing soil health and fertility and thereby improving crop yields. Furthermore, soil organisms affect many aspects of plants, from the underground to the above-ground parts [63]. Agricultural practices such as tillage, crop rotation, fertilizer and pesticide application, and monoculture strongly affect soil fauna and the composition of microbial communities, usually resulting in a reduction of biodiversity [64]. Roots excrete organic compounds into the soil in a process called rhizodeposition, and the compounds secreted in this process are called rhizodeposits [65]. These include enzymes, amino acids, organic acids, sugars, proteins, mucilage, and secondary metabolites such as phenolics (mainly benzenoids, flavonols, lignins, and anthocyanins), isoprenoids (sterols and terpenoids), alkaloids, and sulfur-containing compounds like glucosinolates [62,65]. Underground chemical signaling, primarily mediated by root exudates, is a fundamental ecological process that governs plant-microbe interactions and inter-plant competition [66–70]. An exciting frontier lies in the reciprocal relationship between polyphenols and microbiomes. A parallel line of inquiry should investigate how root exudates, rich in polyphenols, influence soil microbiomes. Understanding this connection is crucial for enhancing nutrient uptake and disease resistance, ultimately impacting the plant’s nutritional output for humans. Phenols and terpenoids often have strong antimicrobial and anti-herbivoral properties. For example, rosmarinic acid, secreted by the roots of sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum) when induced by the pathogenic fungus Pythium ultimum, has shown antimicrobial activity against rhizosphere microorganisms [71]. Furthermore, barley (Hordeum vulgare), when attacked by fungi of the genus Fusarium, produces the antifungal cinnamic acid, which is biosynthesized and released by the plant’s roots [72]. Phenolic acids and flavonoids previously released by plants into the soil can limit the spread and cultivation of seeds for subsequent generations. However, autoallelopathy and autotoxicity can also cause problems for re-sowing or replanting [64,72–74]. Phenolic compounds have several beneficial roles in the soil, but they can also cause autotoxicity in perennial species such as alfalfa (Medicago sativa) and clover (Trifolium repens), which are mainly used as livestock feed. In general, phenolic compounds interfere with hormone activity, membrane permeability, photosynthesis, and the synthesis of organic compounds, and are produced mainly in the absence of nitrogen [75]. Numerous functions of flavonoids are known for controlling plant development, plant-microbe interactions, and plant-animal interactions. One of the conspicuous functions of flavonoids is in flower pigmentation and, relatedly, in attracting pollinators and protecting against UV light. The functions of flavonoids are diverse; for example, flavonoids in poppy flowers (Papaver spp.) represent a wonderful model due to their wide variation in flower color [76]. Also important is the role of flavonoids in cotton, in the production of cotton fibers, as well as in the defense of the cotton plant against pathogens and herbivores [18,36,77]. A further example of the utility of flavonoids and related metabolites, phenylphenalenones, is in the defense of banana plants against attack by the banana weevil, the most significant pest of bananas [78]. One of the best-studied roles of flavonoids in plant-bacterial interactions is their structural role in controlling nodulation gene expression and infection by nitrogen-fixing bacteria, which take up nitrogen and convert it into a plant-available form. Such bacteria live in symbiosis with legumes [64,74]. The binding of flavonoids to transcriptional regulators within rhizobia is necessary for their activation through the transcription of downstream nodulation genes in the expression pathway. Many bacteria also use flavonoids as food sources [78].

3 Significance of Phenolic Compounds for Human Health, Functional Food, and Biotechnology

3.1 Health Benefits and Factors of Variation in Phenolic Content

Phenolic compounds exhibit a wide spectrum of physiological properties, such as anti-allergic, anti-atherogenic, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-thrombotic, cardioprotective, and vasodilatory effects on human health [3,79]. The health benefits of phenolic compounds derive from the consumption of high levels of fruits and vegetables [79]. Beyond these established effects, their health benefits extend to the prevention and management of chronic diseases through anticancer, neuroprotective, and hepatoprotective activities. Furthermore, they play a crucial role in metabolic regulation by exerting antidiabetic and anti-obesity effects, while also exhibiting immunomodulatory, antiviral, and beneficial gut microbiome-modulating properties [80,81]. One of the current global problems is obesity, which has reached epidemic proportions. Available in vitro and in vivo studies have shown the implication of phenolic compounds in reducing food intake, decreasing lipogenesis, increasing lipolysis, stimulating fatty acid β-oxidation, inhibiting adipocyte differentiation and growth, attenuating inflammatory reactions, and suppressing oxidative stress. The investigation of these properties has focused on popular, highly consumed plant products such as cocoa (Theobroma cacao), cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum), olive oil, and beverages like red wine, tea (green, white, and black), and Hibiscus sabdariffa L. tea, among others. Due to their rich content of bioactive phenolics, many of these products are now studied and promoted as functional foods capable of providing health benefits beyond basic nutrition. The World Health Organization (WHO) considers obesity a global epidemic of the developed world [82]. Obesity is a multifactorial disease influenced by behavioral, genetic, and environmental factors, the latter being associated with economic and social status and lifestyle. Obesity is characterized by excess caloric intake combined with low energy expenditure [83]. A higher intake is linked to a 22% lower risk of metabolic syndrome. These compounds improve cardiometabolic health by lowering blood pressure and cholesterol, with specific compounds like oleuropein and tyrosol showing notable effects [84]. Phenols have been shown to improve lipid profiles, enhance endothelial function, and slow kidney decline in people with metabolic syndrome and chronic kidney disease [85]. However, their impact on blood sugar has been limited. From meta-analysis therefore examined the effects of polyphenol-rich interventions on the gut microbiota, oxidative stress, and inflammatory biomarkers. It also explored their potential influence on body composition in overweight and obese adults [86]. The beneficial effects obtained from phenolic compounds are attributed to their antioxidant activity. There are large variations in the total phenol content in different fruits or vegetables, or even for the same fruit or vegetable [87]. Differences may be due to the complexity of these groups of compounds, and the methods of extraction and analysis. In addition, the phenol content in plant-based food depends on a range of internal (genus, species, cultivars) and external (agronomic, environmental, handling, and storage) factors [5]. Differences between species are also pronounced, suggesting that the phenol content in some fruits, i.e., banana (Musa spp.), lychee (Litchi chinensis), mango (Mangifera indica L.), and persimmon (Diospyros kaki), is significantly lower than that of berries and grapes [88,89].

3.2 Bioavailability and Human Metabolism of Phenolic Compounds

The bioavailability of phenolic compounds, which refers to the fraction that is absorbed and becomes available for use in the body, is generally low. After ingestion, these compounds undergo significant metabolic transformations [90]. In the small intestine and liver, Phase I metabolism often involves the addition or exposure of a functional group, while Phase II metabolism, or conjugation, adds a bulky, water-soluble molecule (like a sulfate or glucuronide) to the phenolic compound, making it easier to excrete [91]. The gut microbiome plays a crucial role in this process. Since most phenolic compounds are not absorbed in the small intestine, they travel to the colon where the gut bacteria can cleave complex structures (e.g., glycosides and polymers) into smaller, more easily absorbed molecules, which are often the true bioactive forms [80]. This explains why the same food can have different effects on different people, as the composition of an individual’s gut microbiome can dictate the types and quantities of metabolites produced. The low bioavailability of phenolics can be improved by utilizing encapsulation technologies, such as liposomes and nanoparticles, which protect these compounds from degradation in the harsh digestive environment. Additionally, their absorption can be synergistically enhanced by combining them with bio-enhancers like piperine or by employing food processing methods like fermentation to convert them into more easily absorbable forms [92].

3.3 Phenolic Compounds as a Foundation for Functional Foods

There is great interest worldwide in phytochemicals as bioactive components of food. The roles of fruits, vegetables, and red wine in disease prevention are partly attributed to the antioxidant properties of their constituent polyphenols (vitamins E and C, and carotenoids). Research has shown that many dietary polyphenolic constituents derived from plants are more effective antioxidants in vitro than vitamins E or C and thus can significantly contribute to protective effects in vivo. It is possible to determine the antioxidant activities of plant flavonoids in both aqueous and lipophilic phases and to assess the extent to which the antioxidant potentials of wine and tea can be accounted for by the action of individual polyphenols [61]. The prevention and treatment of cancer using traditional Chinese medicines are attracting increasing public interest. A study by Cai et al. (2004) characterized the antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds of traditional Chinese medicinal plants with anticancer properties, encompassing 112 species from 50 plant families. An improved ABTS+ method was used to assess the total antioxidant capacity (Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity, TEAC) of the medicinal extracts. The TEAC values and total phenolic content of the methanolic extracts of the plants ranged from 46.7 to 17,323 µmol Trolox equivalents/100 g dry weight (DW) and from 0.22 to 50.3 g gallic acid equivalents/100 g DW. The study found a positive, significant linear relationship between antioxidant activity and total phenolic content. The main types of phenolic compounds from most of the tested plants were previously identified and analyzed, and they mainly included phenolic acids, flavonoids, tannins, coumarins, lignans, quinones, stilbenes, and curcuminoids [93]. Flavonoids and other plant phenolics, such as phenolic acids, stilbenes, tannins, lignans, and lignin, are particularly common in leaves, floral tissues, and woody parts such as stems and bark [25,32]. Fruits, especially berries, contain a wide spectrum of flavonoids and phenolic acids that exhibit antioxidant activity. The main flavonoid subgroups in berries and fruits are anthocyanins, proanthocyanidins, flavonols, and catechins. The phenolic acids present in berries and fruits are hydroxylated derivatives of benzoic and cinnamic acid [89]. Studies on the antioxidant activities of fruit extracts have focused mainly on grapes, which are reported to inhibit the oxidation of human low-density lipoprotein (LDL) at a level comparable to wine [94]. Hydroxycinnamic acids, which are commonly present in fruit, have been shown to inhibit LDL oxidation in vitro [95,96]. Among 22 analyzed vegetable species, beans (Phaseolus vulgaris), turnip (Brassica rapa subsp. rapa), corn (Zea mays), and broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica) demonstrated the highest total phenol content per fresh weight [6]. Utilizing the LDL oxidation method to measure the antioxidant quality and quantity, common and pinto beans were ranked highest in antioxidant activity. Other vegetables that placed in the top 10 for antioxidant potency included garlic (Allium sativum), yellow and red onion (Allium cepa), asparagus (Asparagus officinalis), turnip, and potato (Solanum tuberosum). In a separate analysis, the antioxidant activity of select vegetables was found to decrease in the order of broccoli > potato > carrot (Daucus carota subsp. sativus) > onion > pepper (Capsicum annuum) [6,94,97,98]. In addition to being used for flavoring, spices and herbs are also used for their medicinal or antiseptic properties. The preservative effect of many spices and herbs suggests the presence of antioxidant and antimicrobial constituents. Rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus) and sage (Salvia officinalis) were very effective, and oregano (Origanum vulgare), thyme (Thymus vulgaris), turmeric (Curcuma longa), and nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) also showed high antioxidant activity both in soil and as spice extracts. Many leafy spices exhibit strong antioxidant activity [97]. Cereals contain a wide spectrum of phenolic compounds, with significant amounts of phenolic acids like ferulic, caffeic, and p-hydroxybenzoic acid being typical [61]. These compounds are primarily found in a bound form, conjugated with sugars, fatty acids, or proteins. Although phenolic antioxidants in oats have been studied since the 1930s, less attention has been paid to other common cereals. Methanolic extracts of oats have demonstrated a significant antioxidant effect [97–100]. Various woody materials are known to be excellent sources of phenolic compounds. Several phenols have been isolated and identified from coniferous needles, as well as from the bark of birch (Betula pendula), spruce (Picea abies), pine (Pinus spp.), and from the leaves of silver birch (Betula pendula). Pycnogenol (a procyanidin extract from the bark of Pinus maritima) is probably the most studied phenolic wood extract. It has been shown to scavenge free radicals, including hydroxyl and superoxide anions, and may have beneficial effects in preventing arteriosclerosis and other age-related diseases [101]. Globally, dietary habits are shifting, with a lower intake of vegetables and cereals and a rising consumption of meat and cheese [87]. This has led to a lower intake of phenolic compounds, which gained popularity as a research topic in the 1990s following epidemiological studies that linked their consumption to a lower incidence of diseases like cardiovascular disease and cancer [102].

3.4 Functional Foods, Beverages, and Oils with Health Benefit

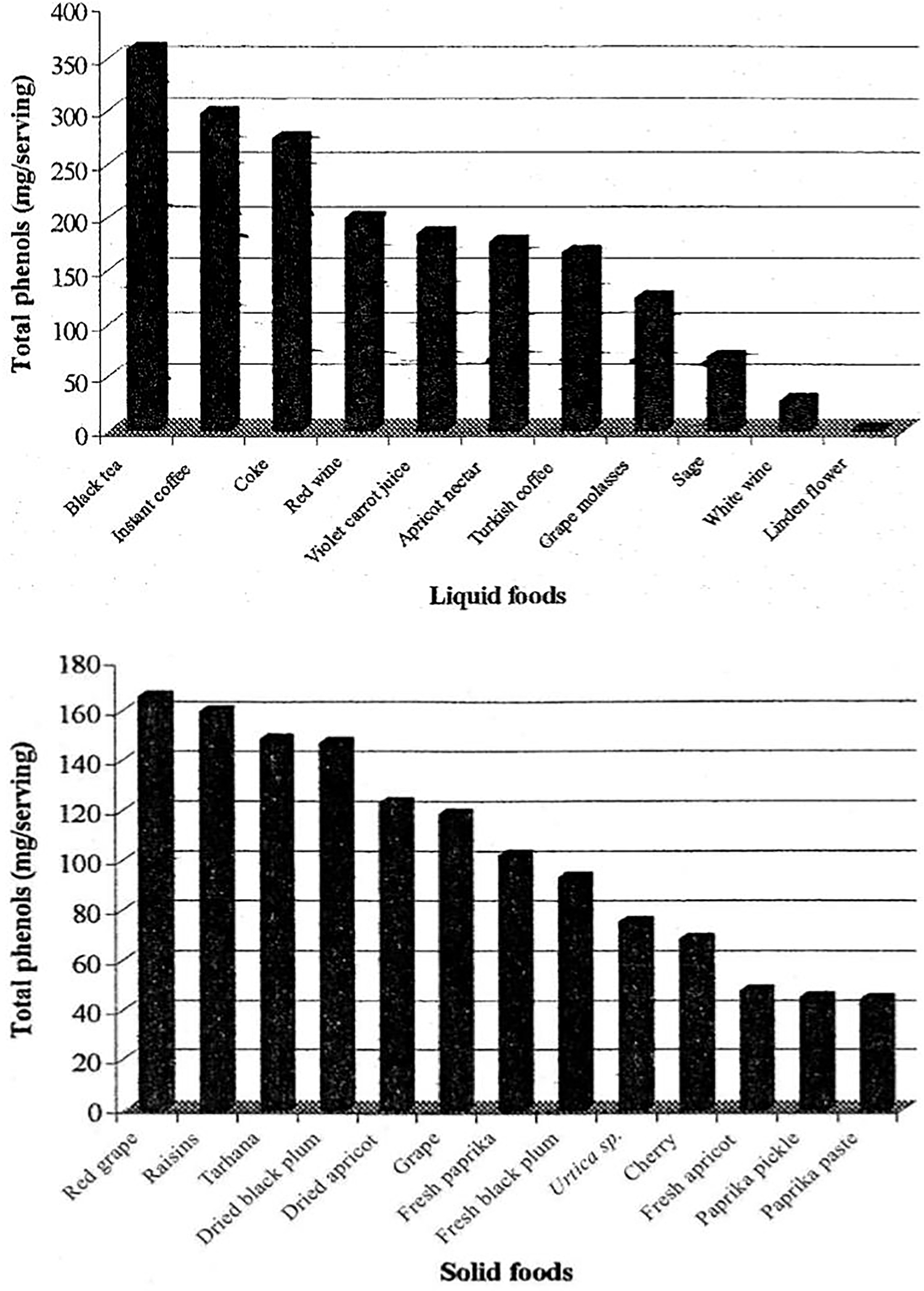

Beyond traditional uses as food colorings, phenolic compounds are now being explored as target compounds against obesity, with specific interest in epigallocatechin gallate, resveratrol, and quercetin [103]. The growing interest in natural products for therapeutic purposes is largely due to their high phenolic compound content, with these compounds and their derivatives are used in the production of drugs for clinical use [104]. Some plants have not only shown in vitro activity, but their anti-obesity properties have also been proven in animal models: grape seeds, wine, tea, lemon verbena leaves, rosehip leaves, fruits, juice and seed oil, cocoa, and olive oil. Other anti-obesity extracts have been obtained from Cornelian cherry (Cornus mas), cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum), and common fig (Ficus carica) [87]. Karakaya et al. (2001) selected 13 liquid and 13 solid foods from a typical Turkish diet for their study and determined the total phenol contents (TP) (Fig. 1) and total antioxidant activity (TAA) [105]. Total phenols were analyzed using the Folin-Ciocalteu procedure, and antioxidant activity in the aqueous phase was assessed by measurement with ABTS (sulfonic acid). According to the total phenol content per serving, the ranking for liquid foods in decreasing order was: black tea > instant coffee > cola > red wine > purple carrot juice > apricot nectar > Turkish coffee > grape molasses > sage > white wine > linden flower. For solid foods, the order was: red grapes > raisins > tarhana > dried black plum > dried apricot > white grapes > fresh paprika > fresh black plum > nettle > cherry > fresh apricot > paprika > pickle > paprika paste [105] (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Total phenols in liquid and solid foods. Source: Karakaya et al., 2001 [105]

The influence of household cooking methods (boiling, microwave cooking, pressure cooking, grilling, frying, and baking) on the antioxidant activity of vegetables was evaluated using various antioxidant activity tests (scavenging of lipoperoxyl and hydroxyl radicals, and TEAC) [89]. Artichoke (Cynara scolymus) was the only vegetable that retained a very high lipoperoxyl radical scavenging ability across all cooking methods. The greatest losses in radical scavenging capacity were observed in cauliflower (Brassica oleracea var. botrytis) after boiling and microwaving, peas (Pisum sativum) after boiling, and zucchini after boiling and frying. Beetroot (Beta vulgaris subsp. vulgaris var. conditiva), green beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), and garlic (Allium sativum) retained their antioxidant activity after most cooking treatments [106]. Swiss chard (Beta vulgaris subsp. cicla) and bell pepper (Capsicum annuum) lost their hydroxyl radical scavenging capacity during all thermal processing methods. Celery (Apium graveolens) increased its antioxidant capacity with all cooking methods except boiling, where it lost 14% of its capacity. Analysis of the ABTS radical scavenging capacity of various vegetables showed that the greatest losses occurred in garlic (Allium sativum) with all methods except microwaving. Among the vegetables that increased their TEAC values were green beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), celery (Apium graveolens), and carrot (Daucus carota subsp. sativus) after all cooking methods (except for green beans after boiling) [106,107]. These three vegetable species showed a low ABTS radical scavenging capacity. Grilling, microwave cooking, and baking alternately produced the smallest losses, while pressure cooking and boiling in water led to the greatest losses, with frying occupying an intermediate position. In short, boiling water is not the best friend when it comes to vegetable preparation [104,108,109]. Cherry (Prunus avium L.) is a tree belonging to the Rosaceae family. The dietary intake of cherry is associated with beneficial health effects. This fruit is rich in nutrients and antioxidant compounds, making it an example of a food thought to prevent chronic and degenerative diseases [110]. The phenol content in cherry contributes to these beneficial health effects. Polyphenol intake is associated with a reduction in cardiovascular disease and cancer risk. In this regard, fruit extracts exhibit free-radical scavenging activities, which consequently help prevent oxidative cell damage, showing anti-inflammatory and antitumor properties. The consumption of cherries is associated with a lower risk of gout and arthritis attacks, as well as a reduction in pain related to gout [111]. The citrus industry produces large quantities of peels and seed residues, which can amount to 50% of the total weight of the processed fruit. By-products from citrus fruits, if used optimally, could be major sources of phenolic compounds, as the peel has been found to contain higher amounts of total phenols compared to the edible parts [112]. The total phenol content in the peels of lemon (Citrus × limon), orange (Citrus × sinensis), and grapefruit (Citrus × paradisi) was 15% higher than in the peeled fruits. The peels of several other fruits have also been found to contain higher amounts of phenolic acids than the edible fleshy parts. For example, the peels of apple (Malus domestica), peach (Prunus persica), and pear (Pyrus communis) contain twice the amount of phenolic acids as the peeled fruits. The peel of nectarine (Prunus persica var. nucipersica) contains at least twice as much phenol as the fleshy part. Peach pits contain 2–2.5 times the amount of total phenolic acids as the edible flesh [113]. The peel of pomegranate (Punica granatum) contains 249.4 mg/g of phenols compared to 24.4 mg/g of phenols in the pulp [114]. By-products from the agri-food industry, such as waste from olive oil and grape processing (seeds and skins), are increasingly recognized as potent sources of valuable phenolic compounds. The non-edible parts of many fruits including the peels and seeds of citrus, tomato, mango, and avocado often contain significantly higher concentrations of phenols than the edible pulp. Furthermore, processing methods can enhance the recovery of these compounds from waste materials. For instance, biological treatments like fermentation with fungi (Rhizopus oligosporus) and physical methods like heat treatment have been shown to release bound phenolics and increase the total yield [113]. A study of eight edible mushroom species determined their total phenolic and flavonoid contents, individual phenolic profiles, and antioxidant properties. Total phenolic content ranged from 1–6 mg/g (dry weight), while flavonoid levels were 0.9–3.0 mg/g. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) analysis revealed that homogentisic acid was present in all species, along with flavonoids like myricetin and catechin. The antioxidant activity of the mushroom extracts was evaluated by their ability to inhibit linoleic acid oxidation. A wide range of efficacy was observed, with Cantharellus cibarius showing the highest inhibition (74%), while Agaricus bisporus was the least effective (10%) [115]. A study of Puupponen-Pimiä et al. (2001) investigated the antimicrobial activity of pure phenolics and extracts from eight Finnish berries against various Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. In general, the berry extracts were more effective at inhibiting Gram-negative bacteria (like Salmonella) than Gram-positive bacteria, a difference likely due to their cell surface structures. Cloudberry, raspberry, and strawberry extracts were the most potent inhibitors of Salmonella. Conversely, the pure flavonoid myricetin inhibited the Gram-positive lactic acid bacteria but had no effect on the Salmonella strain. These results demonstrate the selective antimicrobial properties of different phenolic compounds, which could be useful for developing functional foods and for food preservation [116]. The consumption of olive oil, a cornerstone of the Mediterranean diet, is associated with a reduced incidence of cardiovascular disease. These health benefits are attributed not only to its high content of oleic acid but also to its rich antioxidant composition, particularly tocopherols and phenolic compounds. Therefore, understanding the variation in these phenolic compounds is crucial for clarifying their link to the fruit’s organoleptic and physiological qualities, as well as for optimizing processing techniques to improve product quality [117]. In the last three decades, global olive oil production has increased from 1.4 to 3.3 million tons. The reasons for this increase are not only its fruity and aromatic properties but also its higher level of consumption and popularity (especially in Northern Europe), and it can also be attributed to the promotion of the health effects of olive oil. Olive oil consists of over 98% triacylglycerols, with oleic acid as the dominant esterified fatty acid [118]. Minor components such as free fatty acids, mono- and diacylglycerols, and a wide range of lipids such as hydrocarbons, sterols, aliphatic alcohols, tocopherols, pigments, and phenolic compounds constitute about 2%. Some of these compounds contribute to the unique sensory characteristics of olive oil. Phenolic compounds are of particular interest [117,119]. They are not only responsible for antioxidant activity, which endogenously stabilizes the products for an extended shelf life, but they also impart sensory properties such as bitterness and pungency [120]. A study on the effects of cooking on vegetables found that fresh broccoli had the highest antioxidant activity (78.17% inhibition via DPPH assay), while leek had the lowest (12.20%). The impact of cooking (boiling, steaming, and microwaving) on antioxidant capacity was highly variable depending on the vegetable. The activity in pepper, beans, and spinach significantly increased after cooking. In contrast, the activity in squash, peas, and leek remained unchanged. However, a specific analysis of broccoli showed that after 5 min of boiling or microwaving, the florets lost approximately 65% of their initial antioxidant activity [107]. Phenolic compounds in beer, derived from malt and hops, can directly contribute to some characteristics of beer, mainly flavor, astringency, haze, and body. The degradation of such compounds will inevitably lead to changes in the beer’s freshness. On the other hand, besides being antioxidants, these compounds can significantly protect raw materials in beer from oxidative degradation throughout storage [121], and their incorporation into other foods such as quercetin in cereals or proanthocyanidins from grape seed extract in meat products can similarly enhance antioxidant capacity and act as natural preservatives [122]. This strategic use of polyphenols transforms common foods into vehicles for disease prevention, with studies highlighting their role in improving cardiovascular health and providing anti-inflammatory benefits [123]. While fortification with isolated polyphenols is common, it’s also critical to understand how the polyphenol profile of naturally rich, unprocessed foods changes under different conditions. The concentration and composition of these compounds can be significantly altered by both internal and external factors. For instance, the polyphenol content of fruits and vegetables is influenced by genetics (species and cultivar), but also by environmental conditions like sunlight exposure and soil quality [124,125]. Post-harvest, storage conditions, and handling can further degrade or modify these compounds. This inherent variability explains why the phenolic content of an apple can differ significantly from one variety to another, or even from one farm to the next. The biomedical potential of plant phenolics is well established, but systematic studies connecting plant-derived phenolic diversity with human gut microbiota interactions remain scarce and represent a key frontier.

3.5 Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity of Cereals and Legumes

The total phenolic content (TPC) is significantly altered during germination. While a general increase in soluble TPC is observed, some studies report a decrease in certain legumes like mung bean, soybean, and lentil, which may be due to methodological factors such as reporting results on a wet weight basis, where increasing water content dilutes the concentration [126–128]. The dynamics of bound phenolics are particularly complex. In the initial stages, endogenous enzymes can degrade conjugators, such as carbohydrates and proteins, to release these compounds from cell wall complexes [129]. This can lead to a temporary decrease in the bound fraction. However, as germination progresses and new cells proliferate, soluble phenolics may then be re-conjugated to establish new cell walls, causing the bound fraction to increase again [130,131]. This has been observed in cereals like sprouted brown rice and common wheat. Ultimately, the pattern differs between major plant groups; sprouted cereals tend to contain a higher percentage of their TPC in bound form, whereas legumes often show a higher concentration of soluble phenolics [126]. Sprouted cereal seeds and young cereal grasses, often called microgreens, are increasingly popular as functional foods due to their enhanced nutritional profiles [128]. A prime example is wheatgrass, the young grass of the common wheat plant, consumed for its therapeutic properties [132]. Studies show that wheatgrass exhibits significant antioxidant activity through various mechanisms, including scavenging primary and secondary radicals and inhibiting free-radical-induced membrane damage. This activity reaches its maximum after 7 days of growth. Wheatgrass has been investigated for its potential in treating conditions like ulcerative colitis and thalassemia major, and its extracts have shown antimutagenic properties by inhibiting oxidative DNA damage [133]. In some assays, its antioxidant capacity has even been shown to be superior to standard ascorbic acid [134]. Furthermore, the bioactive potential of these sprouts can be significantly manipulated. For instance, exposing wheat seedlings to moderate UV-B radiation (at an optimal 20 μW/cm2) can significantly increase phenolic content and antioxidant activities; on the fourth day, total phenolic DPPH and ABTS values rose by 26.3%, 25.1%, and 12.0%, respectively. This treatment also altered the activity of key antioxidant enzymes [57]. Different Se concentrations were found to maximize different components: treatment with 0.22 mg/L Se maximized phenolic acids and anthocyanins, while 0.50 mg/L Se yielded the highest flavonoid and vitamin C content [135]. Sprouted legumes also show a dramatic enhancement in bioactivity. A comparative study of six germinated legumes found that peanut exhibited the highest antioxidant activity (32.51% via DPPH assay) and reducing power (84.48%), significantly outperforming species like black bean (7.44% DPPH) and mung bean. The results also highlighted assay-dependent differences, as red bean showed higher DPPH activity than black bean but significantly lower reducing power [136]. Soybean, a widely studied legume, shows significant variation in its valuable isoflavone content depending on the cultivar and processing method; content in cultivars ranges from 525–986 mg/kg, while in soy products it ranges from 32.9–795 mg/kg, with sprouts containing the highest levels [137]. Research has also optimized extraction protocols for soybean sprouts, identifying the radicle of 5-day-old sprouts as the most potent source of polyphenols, with an optimal yield of 19.801 mg GE/g DW under specific conditions [138]. As a functional alternative, chickpeas have been shown to have comparable isoflavone levels to soy but with a lower lipid content, making them a promising option for managing obesity and type 2 diabetes [139]. Beyond their nutritional roles, these compounds exhibit other biological activities. Phenolic extracts from soybeans have demonstrated protective antifungal activity against mycotoxin contamination, such as aflatoxin B1 [140]. Conversely, some phenolics like cinnamic acid can act as allelochemicals, with concentrations as low as 0.05 mM inhibiting the root and seedling growth of soybean [39]. This body of research underscores that phenolic compounds are a diverse class of phytochemicals with a wide range of biological activities including the ability to inhibit cell proliferation, modulate transcription factors, and arrest signaling pathways giving them great potential in treating and preventing human diseases [141].

3.6 Challenges & Controversies

The ecological role of polyphenols as allelopathic agents compounds that inhibit the growth of competing plants does not directly translate to their effects in mammalian systems. While these compounds are protective for plants, their physiological impact on human health can be unpredictable [142]. This raises questions about whether certain polyphenols, particularly at high concentrations, might exert unintended effects or variable bioactivity across individuals. A central paradox in polyphenol research is the disconnect between their potent in vitro antioxidant capacity and their observed mechanisms of action in vivo [143]. Polyphenols are generally poorly absorbed and rapidly metabolized, meaning they typically do not accumulate in tissues at sufficient concentrations to function as direct free-radical scavengers. Instead, their systemic benefits are thought to arise from their role as signaling molecules that modulate cellular pathways, such as activating endogenous antioxidant and anti-inflammatory defense systems, rather than acting as a direct antioxidant [144]. The efficacy of polyphenol interventions in human trials is often inconsistent. This variability can be attributed to several factors, including differences in bioavailability, the specific chemical structure of the polyphenol, dosage, the food matrix, and interactions with the individual’s gut microbiota [145]. The results of controlled in vitro studies frequently fail to be replicated in complex human (in vivo) trials, underscoring the challenge of translating laboratory findings into clinically significant outcomes and highlighting the need for more standardized and robust research methodologies.

Modern dietary patterns are trending towards becoming increasingly nutrient-poor [130,146,147], which necessitates research into methods for achieving and restoring the nutritional value of cereals, vegetables, and fruits. With the rise of personalized nutrition, plant-based bioactives like phenolics are gaining traction not only as functional food ingredients but also as candidates for bio-pharmaceutical formulations and as key elements in designing regenerative food systems aligned with both planetary and human health. Keeping the continued development of biotechnological approaches like metabolic engineering for targeted production, and the optimization of agricultural and processing techniques to maximize the functional properties of our food. Also, Future research should focus on elucidating how environmental factors such as climate change, elevated CO2, and soil microbiome dynamics influence phenolic biosynthesis and allocation in crops. The exploration of phenolic compounds remains a critical and promising frontier, bridging the gap between plant science, human nutrition, and preventative medicine.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded as a part of the institutional scientific project entitled “Treatment of seed and plantlets with wild plant-derived products” financed by Faculty of Agrobiotechnical Sciences Osijek. URL: https://www.croris.hr/projekti/projekt/9938 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Lucija Galić, Miroslav Lisjak; Writing—original draft, Miroslav Lisjak, Lucija Galić; Writing—review & editing, Zdenko Lončarić. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Hollman PC. Evidence for health benefits of plant phenols: local or systemic effects? J Sci Food Agric. 2001;81(9):842–52. doi:10.1002/jsfa.900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Pérez-Torres I, Castrejón-Téllez V, Soto ME, Rubio-Ruiz ME, Manzano-Pech L, Guarner-Lans V. Oxidative stress, plant natural antioxidants, and obesity. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(4):1786. doi:10.3390/ijms22041786. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Kanti B, Pandey S, Ibrahim R. Plant polyphenols as dietary antioxidants in human health and disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2009;2(5):270–8. doi:10.4161/oxim.2.5.9498. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Cory H, Passarelli S, Szeto J, Tamez M, Mattei J. The role of polyphenols in human health and food systems: a mini-review. Front Nutr. 2018;5:87. doi:10.3389/fnut.2018.00087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Manach C, Scalbert A, Morand C, Rémésy C, Jiménez L. Polyphenols: food sources and bioavailability. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(5):727–47. doi:10.1093/ajcn/79.5.727. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Vinson JA, Hao Y, Su X, Zubik L. Phenol antioxidant quantity and quality in foods: vegetables. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46(9):3630–4. doi:10.1021/jf980295o. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Maeda H, Dudareva N. The shikimate pathway and aromatic amino Acid biosynthesis in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2012;63(1):73–105. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105439. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Herrmann KM, Weaver LM. The shikimate pathway. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1999;50(1):473–503. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.473. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Tohge T, Watanabe M, Hoefgen R, Fernie AR. The evolution of phenylpropanoid metabolism in the green lineage. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;48(2):123–52. doi:10.3109/10409238.2012.758083. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Pevalek-Kozlina B. Fiziologija Bilja. Zagreb, Croatia: Profil International; 2003. [Google Scholar]

11. Vogt T. Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Mol Plant. 2010;3(1):2–20. doi:10.1093/mp/ssp106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Dixon RA, Paiva NL. Stress-induced phenylpropanoid metabolism. Plant Cell. 1995;7(7):1085. doi:10.2307/3870059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Hahlbrock K, Scheel D. Physiology and molecular biology of phenylpropanoid metabolism. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1989;40(1):347–69. doi:10.1146/annurev.pp.40.060189.002023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Fraser CM, Chapple C. The phenylpropanoid pathway in Arabidopsis. Arab Book. 2011;9:e0152. doi:10.1199/tab.0152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Seigler DS. Cumarins. In: Plant secondary metabolism. New York, NY, USA: Springer Science+Business Media; 1998. p. 130–8. [Google Scholar]

16. Hearst JE, Isaacs ST, Kanne D, Rapoport H, Straub K. The reaction of the psoralens with deoxyribonucleic acid. Q Rev Biophys. 1984;17(1):1–44. doi:10.1017/s0033583500005242. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Yaqoob U, Jan N, Raman PV, Siddique KHM, John R. Crosstalk between brassinosteroid signaling, ROS signaling and phenylpropanoid pathway during abiotic stress in plants: does it exist? Plant Stress. 2022;4(1):100075. doi:10.1016/j.stress.2022.100075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Das C. A review on understanding the plant’s secret language for communication and its application. Haya Saudi J Life Sci. 2024;9(1):1–11. doi:10.36348/sjls.2024.v09i01.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Do TMH, Choi M, Kim JK, Kim YJ, Park C, Park CH, et al. Impact of light and dark treatment on phenylpropanoid pathway genes, primary and secondary metabolites in Agastache rugosa transgenic hairy root cultures by overexpressing Arabidopsis transcription factor AtMYB12. Life. 2023;13(4):1042. doi:10.3390/life13041042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Wang W, Zheng M, Shen Z, Meng H, Chen L, Li T, et al. Tolerance enhancement of Dendrobium Officinale by salicylic acid family-related metabolic pathways under unfavorable temperature. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24(1):770. doi:10.1186/s12870-024-05499-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Jańczak-Pieniążek M, Cichoński J, Michalik P, Chrzanowski G. Effect of heavy metal stress on phenolic compounds accumulation in winter wheat plants. Molecules. 2023;28(1):241. doi:10.3390/molecules28010241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Ma J, Wu X, Xie H, Geng G, Qiao F. Molecular regulation of phenylpropanoid and flavonoid biosynthesis pathways based on transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses in oat seedlings under sodium selenite treatment. Biology. 2025;14(9):1131. doi:10.3390/biology14091131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Inderjit, Duke SO. Ecophysiological aspects of allelopathy. Planta. 2003;217(4):529–39. doi:10.1007/s00425-003-1054-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Wang NQ, Kong CH, Wang P, Meiners SJ. Root exudate signals in plant-plant interactions. Plant Cell Env. 2021;44(4):1044–58. doi:10.1111/pce.13892. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Boerjan W, Ralph J, Baucher M. Lignin biosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2003;54(1):519–46. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134938. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Vanhevel Y, De Moor A, Muylle H, Vanholme R, Boerjan W. Breeding for improved digestibility and processing of lignocellulosic biomass in Zea mays. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1419796. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1419796. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Khoddami A, Wilkes MA, Roberts TH. Techniques for analysis of plant phenolic compounds. Molecules. 2013;18(2):2328–75. doi:10.3390/molecules18022328. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Mierziak J, Kostyn K, Kulma A. Flavonoids as important molecules of plant interactions with the environment. Molecules. 2014;19(10):16240–65. doi:10.3390/molecules191016240. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Kuhn BM, Geisler M, Bigler L, Ringli C. Flavonols accumulate asymmetrically and affect auxin transport in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2011;156(2):585–95. doi:10.1104/pp.111.175976. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Falcone Ferreyra ML, Rius SP, Casati P. Flavonoids: biosynthesis, biological functions, and biotechnological applications. Front Plant Sci. 2012;3:222. doi:10.3389/fpls.2012.00222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Jeffers MD. Tannins as anti-inflammatory agents [master’s thesis]. Oxford, OH, USA: Faculty of Miami University; 2006. [Google Scholar]

32. Barbehenn RV, Peter Constabel C. Tannins in plant-herbivore interactions. Phytochemistry. 2011;72(13):1551–65. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.01.040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Ellis BE. Degradation of phenolic compounds by fresh-water algae. Plant Sci Lett. 1977;8(3):213–6. doi:10.1016/0304-4211(77)90183-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Barz W, Hoesel W. Metabolism and degradation of phenolic compounds in plants. In: Biochemistry of plant phenolics. Boston, MA, USA: Springer; 1979. p. 339–69. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-3372-2_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Ninkuu V, Aluko OO, Yan J, Zeng H, Liu G, Zhao J, et al. Phenylpropanoids metabolism: recent insight into stress tolerance and plant development cues. Front Plant Sci. 2025;16:1571825. doi:10.3389/fpls.2025.1571825. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Ramaroson ML, Koutouan C, Helesbeux JJ, Le Clerc V, Hamama L, Geoffriau E, et al. Role of phenylpropanoids and flavonoids in plant resistance to pests and diseases. Molecules. 2022;27(23):8371. doi:10.3390/molecules27238371. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Upadhyay SK, Srivastava AK, Rajput VD, Chauhan PK, Bhojiya AA, Jain D, et al. Root exudates: mechanistic insight of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria for sustainable crop production. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:916488. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2022.916488. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Rodríguez-Bonilla P, Gandía-Herrero F, Matencio A, García-Carmona F, López-Nicolás JM. Comparative study of the antioxidant capacity of four stilbenes using ORAC, ABTS+, and FRAP techniques. Food Anal Meth. 2017;10(9):2994–3000. doi:10.1007/s12161-017-0871-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Salvador VH, Lima RB, dos Santos WD, Soares AR, Böhm PAF, Marchiosi R, et al. Cinnamic acid increases lignin production and inhibits soybean root growth. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69105. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Khatri P, Chen L, Rajcan I, Dhaubhadel S. Functional characterization of Cinnamate 4-hydroxylase gene family in soybean (Glycine max). PLoS One. 2023;18(5):e0285698. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0285698. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Schink B, Philipp B, Müller J. Anaerobic degradation of phenolic compounds. Naturwissenschaften. 2000;87(1):12–23. doi:10.1007/s001140050002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Skroza D, Šimat V, Vrdoljak L, Jolić N, Skelin A, Čagalj M, et al. Investigation of antioxidant synergisms and antagonisms among phenolic acids in the model matrices using FRAP and ORAC methods. Antioxidants. 2022;11(9):1784. doi:10.3390/antiox11091784. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Kumar K, Debnath P, Singh S, Kumar N. An overview of plant phenolics and their involvement in abiotic stress tolerance. Stresses. 2023;3(3):570–85. doi:10.3390/stresses3030040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Nguyen BV, Kim JK, Lim J, Kim K, Sathasivam R, Cho DH, et al. Enhancement of phenylpropanoid accumulation and antioxidant activities of Agastache rugosa transgenic hairy root cultures by overexpressing the maize LC transcription factor. Appl Sci. 2024;14(20):9617. doi:10.3390/app14209617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Dixon RA, Achnine L, Kota P, Liu CJ, Srinivasa Reddy MS, Wang L. The phenylpropanoid pathway and plant defence-a genomics perspective. Mol Plant Pathol. 2002;3(5):371–90. doi:10.1046/j.1364-3703.2002.00131.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Mittler R. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7(9):405–10. doi:10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02312-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Schmidt A, Kunert KJ. Lipid peroxidation in higher plants: the role of glutathione reductase. Plant Physiol. 1986;82(3):700–2. doi:10.1104/pp.82.3.700. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Grace SC, Logan BA. Energy dissipation and radical scavenging by the plant phenylpropanoid pathway. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci. 2000;355(1402):1499–510. doi:10.1098/rstb.2000.0710. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Kannan S, Sams T, Maury J, Workman CT. Reconstructing dynamic promoter activity profiles from reporter gene data. ACS Synth Biol. 2018;7(3):832–41. doi:10.1021/acssynbio.7b00223. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Schandry N, Becker C. Allelopathic plants: models for studying plant-interkingdom interactions. Trends Plant Sci. 2020;25(2):176–85. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2019.11.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Wang Y, Wang M, Chen Y, Hu W, Zhao S. Integrated metabolomic and transcriptomic analysis provides insights into the browning of walnut endocarps. Front Plant Sci. 2025;16:1582209. doi:10.3389/fpls.2025.1582209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Guerrieri E, Rasmann S. Exposing belowground plant communication. Science. 2024;384(6693):272–3. doi:10.1126/science.adk1412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Vanholme B, El Houari I, Boerjan W. Bioactivity: phenylpropanoids’ best kept secret. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2019;56:156–62. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2018.11.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Pagnotta MA. Molecular breeding for abiotic stress tolerance in crops: recent developments and future prospectives. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(18):9164. doi:10.3390/ijms26189164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Jalouli M, Rahman MA, Biswas P, Rahman H, Harrath AH, Lee IS, et al. Targeting natural antioxidant polyphenols to protect neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative diseases: a comprehensive review. Front Pharmacol. 2025;16:1492517. doi:10.3389/fphar.2025.1492517. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Lai G, Fu P, He L, Che J, Wang Q, Lai P, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated CHS2 mutation provides a new insight into resveratrol biosynthesis by causing a metabolic pathway shift from flavonoids to stilbenoids in Vitis davidii cells. Hortic Res. 2025;12(1):uhae268. doi:10.1093/hr/uhae268. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Cheng F, Cheng Z. Research progress on the use of plant allelopathy in agriculture and the physiological and ecological mechanisms of allelopathy. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:1020. doi:10.3389/fpls.2016.01697. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Zuo H, Chen J, Lv Z, Shao C, Chen Z, Zhou Y, et al. Tea-derived polyphenols enhance drought resistance of tea plants (Camellia sinensis) by alleviating jasmonate-isoleucine pathway and flavonoid metabolism flow. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(7):3817. doi:10.3390/ijms25073817. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Camli-Saunders D, Villouta C. Root exudates in controlled environment agriculture: composition, function, and future directions. Front Plant Sci. 2025;16:1567707. doi:10.3389/fpls.2025.1567707. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Bowles D, Lim EK, Poppenberger B, Vaistij FE. Glycosyltransferases of lipophilic small molecules. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57(1):567–97. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Rice-Evans CA, Miller NJ, Paganga G. Structure-antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and phenolic acids. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;20(7):933–56. doi:10.1016/0891-5849(95)02227-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Lehmann J, Bossio DA, Kögel-Knabner I, Rillig MC. The concept and future prospects of soil health. Nat Rev Earth Env. 2020;1(10):544–53. doi:10.1038/s43017-020-0080-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Obasi PN, Tenebe OA. Omodara role of soil microbial diversity in mitigating soil-borne diseases and postharvest losses. Niger Agric J. 2024;55(3):297–319. [Google Scholar]

64. Shah AM, Khan IM, Shah TI, Bangroo SA, Kirmani NA, Nazir S, et al. Soil microbiome: a treasure trove for soil health sustainability under changing climate. Land. 2022;11(11):1887. doi:10.3390/land11111887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Vives-Peris V, de Ollas C, Gómez-Cadenas A, Pérez-Clemente RM. Root exudates: from plant to rhizosphere and beyond. Plant Cell Rep. 2020;39(1):3–17. doi:10.1007/s00299-019-02447-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Park S, Kim H, Bang M, Um BH, Cha JW. A study on the photoisomerization of phenylpropanoids and the differences in their radical scavenging activity using in situ NMR spectroscopy and on-line radical scavenging activity analysis. Appl Biol Chem. 2024;67(1):69. doi:10.1186/s13765-024-00925-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Ghitti E, Rolli E, Vergani L, Borin S. Flavonoids influence key rhizocompetence traits for early root colonization and PCB degradation potential of Paraburkholderia xenovorans LB400. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1325048. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1325048. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Wang X, Liu Y, Tian X, Guo J, Luan Y, Wang D. Root exudates mediate the production of reactive oxygen species in rhizosphere soil: formation mechanisms and ecological effects. Plants. 2025;14(9):1395. doi:10.3390/plants14091395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Ahmad Bhat M, Mishra AK, Jan S, Bhat MA, Kamal MA, Rahman S, et al. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria in plant health: a perspective study of the underground interaction. Plants. 2023;12(3):629. doi:10.3390/plants12030629. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Wankhade A, Wilkinson E, Britt DW, Kaundal A. A review of plant-microbe interactions in the rhizosphere and the role of root exudates in microbiome engineering. Appl Sci. 2025;15(13):7127. doi:10.3390/app15137127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Berg G. Plant-microbe interactions promoting plant growth and health: perspectives for controlled use of microorganisms in agriculture. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;84(1):11–8. doi:10.1007/s00253-009-2092-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Dutta P, Muthukrishnan G, Kutalingam Gopalasubramaiam S, Dharmaraj R, Karuppaiah A, Loganathan K, et al. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) and its mechanisms against plant diseases for sustainable agriculture and better productivity. BIOCELL. 2022;46(8):1843–59. doi:10.32604/biocell.2022.019291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Ijaz U, Zhao C, Shabala S, Zhou M. Molecular basis of plant-pathogen interactions in the agricultural context. Biology. 2024;13(6):421. doi:10.3390/biology13060421. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Ho-Plágaro T, García-Garrido JM. Molecular regulation of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(11):5960. doi:10.3390/ijms23115960. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Guerrieri A, Dong L, Bouwmeester HJ. Role and exploitation of underground chemical signaling in plants. Pest Manag Sci. 2019;75(9):2455–63. doi:10.1002/ps.5507. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Grotewold E. The genetics and biochemistry of floral pigments. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:761–80. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Liu W, Feng Y, Yu S, Fan Z, Li X, Li J, et al. The flavonoid biosynthesis network in plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(23):12824. doi:10.3390/ijms222312824. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Mathesius U. Flavonoid functions in plants and their interactions with other organisms. Plants. 2018;7(2):30. doi:10.3390/plants7020030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Scalbert A, Johnson IT, Saltmarsh M. Polyphenols: antioxidants and beyond. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81(1):215S–7S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/81.1.215s. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Domínguez-López I, López-Yerena A, Vallverdú-Queralt A, Pallàs M, Lamuela-Raventós RM, Pérez M. From the gut to the brain: the long journey of phenolic compounds with neurocognitive effects. Nutr Rev. 2025;83(2):e533–46. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuae034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Dai J, Mumper RJ. Plant phenolics: extraction, analysis and their antioxidant and anticancer properties. Molecules. 2010;15(10):7313–52. doi:10.3390/molecules15107313. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. WHO (World Health Organization). Obesity and Overweight [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Otc 28]. Available from: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/health-topics/obesity. [Google Scholar]

83. Hruby A, Hu FB. The epidemiology of obesity: a big picture. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(7):673–89. doi:10.1007/s40273-014-0243-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Seong GU, Hwang IW, Chung SK. Antioxidant capacities and polyphenolics of Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. Pekinensis) leaves. Food Chem. 2016;199(4):612–8. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.12.066. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Hadinata E, Taslim NA, Nurkolis F. Fruit- and vegetable-derived polyphenols improve metabolic and renal outcomes in adults with metabolic syndrome and chronic kidney disease: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Nutr Clín DIET Hosp. 2025;45(2):476–87. doi:10.12873/452hadinata. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. González-Gómez Á, Cantone M, García-Muñoz AM, Victoria-Montesinos D, Lucas-Abellán C, Serrano-Martínez A, et al. Effect of polyphenol-rich interventions on gut microbiota and inflammatory or oxidative stress markers in adults who are overweight or obese: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2025;17(15):2468. doi:10.3390/nu17152468. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Rodríguez-Pérez C, Segura-Carretero A, Del Mar Contreras M. Phenolic compounds as natural and multifunctional anti-obesity agents: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2019;59(8):1212–29. doi:10.1080/10408398.2017.1399859. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Rice-Evans C, Miller N, Paganga G. Antioxidant properties of phenolic compounds. Trends Plant Sci. 1997;2(4):152–9. doi:10.1016/S1360-1385(97)01018-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

89. Pérez-Jiménez J, Neveu V, Vos F, Scalbert A. Identification of the 100 richest dietary sources of polyphenols: an application of the Phenol-Explorer database. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64(Suppl3):S112–20. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2010.221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Mosele JI, Motilva MJ. Phenol biological metabolites as food intake biomarkers, a pending signature for a complete understanding of the beneficial effects of the Mediterranean diet. Nutrients. 2021;13(9):3051. doi:10.3390/nu13093051. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Narduzzi L, Agulló V, Favari C, Tosi N, Mignogna C, Crozier A, et al. (Poly)phenolic compounds and gut microbiome: new opportunities for personalized nutrition. Microbiome Res Rep. 2022;1(3):16. doi:10.20517/mrr.2022.06. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Fang Z, Bhandari B. Encapsulation of polyphenols—a review. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2010;21(10):510–23. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2010.08.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Cai Y, Luo Q, Sun M, Corke H. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds of 112 traditional Chinese medicinal plants associated with anticancer. Life Sci. 2004;74(17):2157–84. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Heinonen IM, Meyer AS, Frankel EN. Antioxidant activity of berry phenolics on human low-density lipoprotein and liposome oxidation. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46(10):4107–12. doi:10.1021/jf980181c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Meyer AS, Donovan JL, Pearson DA, Waterhouse AL, Frankel EN. Fruit hydroxycinnamic acids inhibit human low-density lipoprotein oxidation in vitro. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46(5):1783–7. doi:10.1021/jf9708960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

96. Skrovankova S, Sumczynski D, Mlcek J, Jurikova T, Sochor J. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity in different types of berries. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(10):24673–706. doi:10.3390/ijms161024673. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Kähkönen MP, Hopia AI, Vuorela HJ, Rauha JP, Pihlaja K, Kujala TS, et al. Antioxidant activity of plant extracts containing phenolic compounds. J Agric Food Chem. 1999;47(10):3954–62. doi:10.1021/jf990146l. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Carlsen MH, Halvorsen BL, Holte K, Bøhn SK, Dragland S, Sampson L, et al. The total antioxidant content of more than 3100 foods, beverages, spices, herbs and supplements used worldwide. Nutr J. 2010;9(1):3. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-9-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]