Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Combining Traditional Breeding with Molecular Techniques: An Integrative Approach

Department of Genetics and Plant Breeding, Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University, Dhaka, 1207, Bangladesh

* Corresponding Author: Md. Abdur Rahim. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant Biodiversity (Cultivated and Wild Flora) and Its Utility in Plant Breeding)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(8), 2313-2346. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.067633

Received 08 May 2025; Accepted 08 August 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Molecular tools have drawn the attention of modern plant breeders for its great precision and superiority. As the global population is increasing gradually, food production should be enhanced to feed the growing population. Therefore, precise and fast breeding tools are becoming obvious. Moreover, climate change has become a critical issue in crop improvement. Advanced breeding methods are vital to combat the impact of climate change, including biotic and abiotic stresses. Major molecular techniques, such as ‘CRISPR-Cas’ mediated ‘genome editing’, ‘marker-assisted selection (MAS)’, ‘whole genome sequencing’, ‘RNAi’, transgenic approach, ‘high-throughput phenotyping (HTP)’, mutation breeding, have been proven superior over traditional breeding in terms of precision, efficiency, and speed in developing stress-resistant improved varieties. This review explores the potential and superiority of molecular breeding methods and highlights the gaps (time, cost, efficiency, etc.) in traditional breeding methods, where modern breeding programs, as mentioned, are effective. Furthermore, this review will focus on the necessity of key modern plant breeding techniques as a foundation for sustainable farming practices to address emerging environmental challenges, ensure food security, and improve the yield and quality of crops.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileThe world’s population is projected to rise by 9.7 billion in the year 2050, and food demand will increase by almost 70% over current levels [1]. In this 21st century, a rapidly growing global population poses significant challenges for food production, exacerbated by declining arable land, soil degradation, water scarcity, and the detrimental impacts of climate change, including global warming and shifting weather patterns [2]. Crop plants encounter a variety of abiotic and biotic stressors due to the shifting of global climate conditions, resulting in substantial reductions in their growth, productivity, and yield production [3]. The main constraint to developing high-yielding as well as climate-resilient varieties has intensified due to worsening climatic conditions, including elevated atmospheric CO2 levels, heat stress, temperature fluctuations, and irregular rainfall patterns [4]. Moreover, the drastic alterations in weather patterns driven by climate change are intensifying drought and heat stress, leading to drastic yield losses for farmers worldwide [5]. Ensuring food security alongside environmental sustainability has emerged as one of the greatest challenges for researchers, particularly in response to escalating population pressures worldwide.

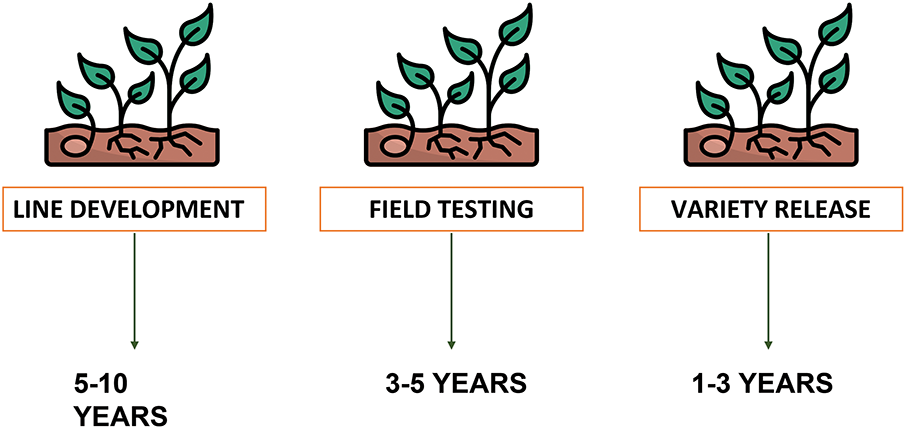

Plant breeding is regarded as one of the oldest human endeavours, with the selection of more beneficial and productive plants for both human and animal use dating back approximately 10,000 years [6]. Conventional plant breeding has substantially improved crop yields in numerous crops, enhanced tolerance to abiotic and biotic stresses, and successfully shortened crop life cycles within a single growing season [7,8]. The traditional breeding method is time-intensive and laborious (Fig. 1), particularly when dealing with traits of low heritability, making the process relatively inefficient [9].

Figure 1: Stagewise time for traditional plant breeding

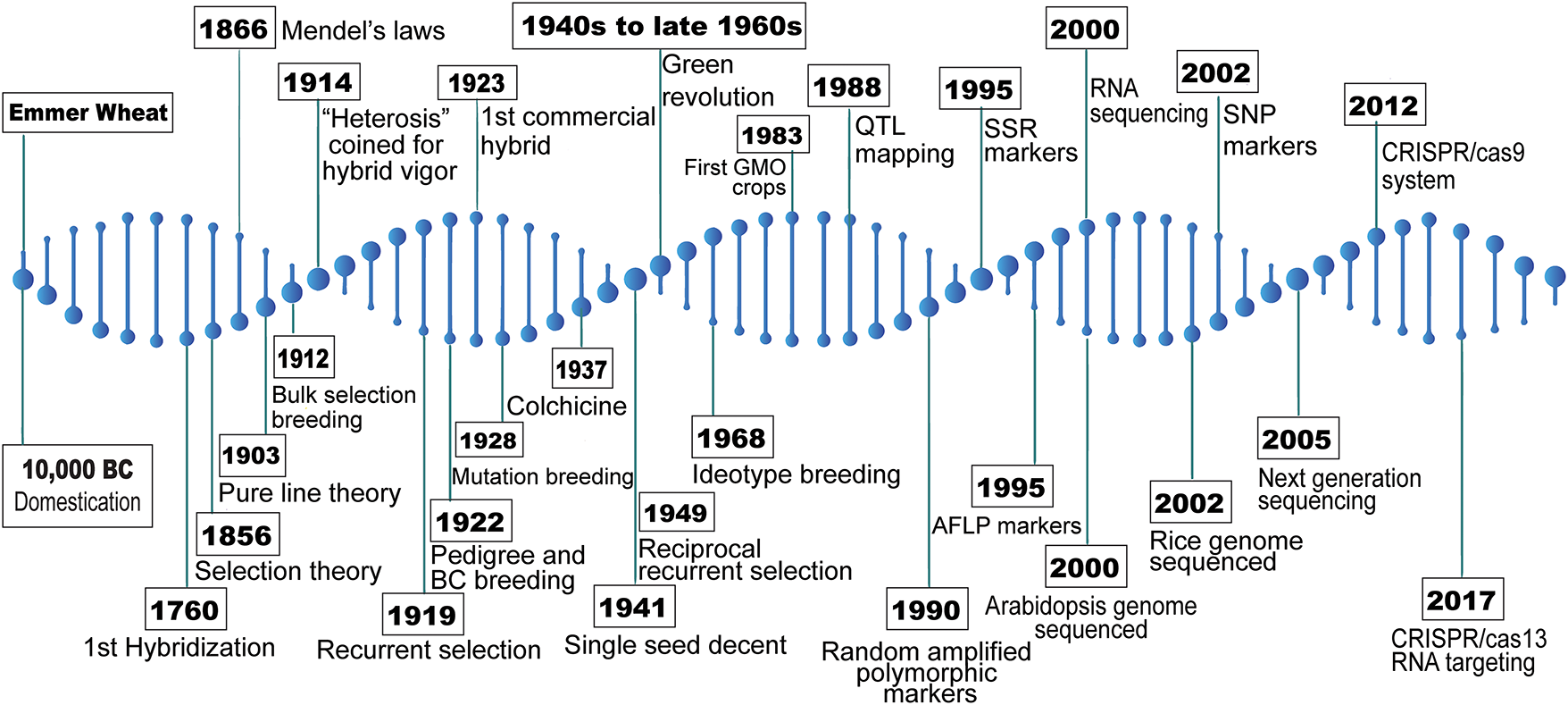

Conventional breeding method heavily depends on the phenotype, making selection prone to errors due to the strong influence of genotype × environment interactions [10]. To address these challenges, recent scientific advances have greatly expanded the possibilities and driven major innovations in plant breeding (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Historical scientific advancements in the evolution of plant breeding

In numerous crops, sequencing of the whole genome has advanced crop functional genomics into the era of high-throughput and big data analysis [11]. High-throughput phenotyping (HTP) integrates advanced technologies and data analysis to automatically capture detailed information on traits, for instance, plant growth, resistance to diseases, yield components, and stress tolerance [12]. New avenues of crop development have been made possible by integrating ‘artificial intelligence (AI)’ and ‘machine learning (ML)’ with HTP data [13]. Since the first plant genome sequence of Arabidopsis thaliana in 2000, genomics technologies have advanced significantly, enabling researchers to adopt novel algorithms and approaches to generate transcriptome, genome, and epigenome data, thereby deepening insights into plant genetics across model as well as crop species [14]. Additionally, next-generation sequencing (NGS) enables massively parallel sequencing, facilitating rapid whole-genome analysis within a single day [15]. DNA markers encompass various types, including ‘random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD)’, ‘simple sequence repeats (SSRs)’, ‘restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP)’, ‘inter-simple sequence repeat (ISSR)’, ‘amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP)’, and ‘single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)’ [16]. In modern breeding, SNPs are extensively used as DNA markers to identify genomic regions linked to important traits, thereby advancing the breeding process [17]. Molecular markers are employed to identify specific genomic regions or gene positions associated with important plant traits. ‘High-throughput SNP genotyping’ offers several advantages over earlier marker systems, including a high marker density and the ability to rapidly process large populations with increased accuracy and efficiency [18]. The concept of ‘marker-assisted selection (MAS)’ has been widely employed to justify the identification and cloning of hundreds of genes and improve their polygenic traits across various plant species [19]. Additionally, QTL analysis links known functional proteins and regulatory components to QTLs through candidate gene analysis in plant genomics, improving our understanding of complex characteristics like plant-pathogen interactions [20]. Modern breeding programs have entered a transformative era of genetic improvement, driven by the beginning of genome-editing technologies. Among these, the ‘CRISPR/Cas9’ technology has evolved as a powerful ‘genome-editing’ tool, widely applied across diverse organisms, including plants [21]. This advanced genome-editing tool holds significant potential for enhancing crop resilience to abiotic and biotic stresses through precise gene edits conferring traits such as drought tolerance, cold resilience, salinity tolerance, and disease resistance [22]. RNA interference (RNAi) technology also offers significant benefits, including nutritional enhancement, morphological modification, and increased synthesis of secondary metabolites, the development of novel quality traits, and enhanced protection against abiotic and biotic stresses [23]. Various crops, including rice, tomato, maize, mustard, and potato, have been genetically engineered to exhibit improved resistance to herbicides, viruses, insect pests, and a range of abiotic as well as biotic stressors. Transgenic plants can express recombinant proteins, including bacterial and viral antigens, as well as therapeutic antibodies [24].

Consequently, this review aims to delineate a comprehensive overview of fundamental molecular approaches in crop breeding. This review explores modern molecular tools that complement traditional breeding by introducing innovative technologies to enhance crop improvement and food production. The integration of molecular tools (marker-assisted selection, high-throughput phenotyping, genomic selection, genome editing, etc.) with the field-test framework of traditional breeding enables genetic gain, transfer of complex traits, and accelerates the breeding program. This integrated approach enables the selection of plants carrying desirable genes before the expression of phenotypic traits, thereby conserving time and resources. This approach not only enhances the efficiency of variety development but also strengthens the adaptability of crops to dynamic environmental conditions and evolving biotic and abiotic stresses. Molecular tools like marker-assisted selection (MAS), genomic selection (GS), and QTL mapping allow breeders to target specific genes responsible for traits like yield, disease resistance, or stress tolerance, which will be very crucial for developing climate-resilient crop varieties. Moreover, this review offers a comprehensive analysis to create a more powerful, precise, and efficient crop improvement system, enabling breeders to meet the global demand for sustainable, resilient, and high-yielding crops in a shorter timeframe.

2 CRISPR-Mediated Genome Editing

The CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing technique, short for ‘Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats’, consists of short, repeating sequences of genetic material. It is naturally found in most archaea and many bacterial species. CRISPR/Cas9 and its associated proteins form a highly effective defense system that protects plants from foreign agents such as viruses, bacteria, and other harmful elements [25]. CRISPR/Cas9 is commonly used to introduce mutations in specific target genes within a system [26]. The system consists of two key components: an endonuclease enzyme (Cas9) and a target-specific RNA known as single guide RNA (sgRNA) [27,28]. CRISPR/Cas9 components, whether in the form of DNA or RNA, are introduced into plant cells to enable precise genome editing. This system strategically cuts plant DNA at specific sites, triggering the cell’s natural repair mechanisms to restore genome integrity [25]. As a result, various modifications may occur in the targeted sequence. When the repair process takes place through non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR), small insertions or deletions can arise, potentially leading to gene mutations [25]. Once the repair is complete, the drive allele is duplicated onto the wild-type chromosome, effectively replacing the original wild-type DNA sequences within the genome [28].

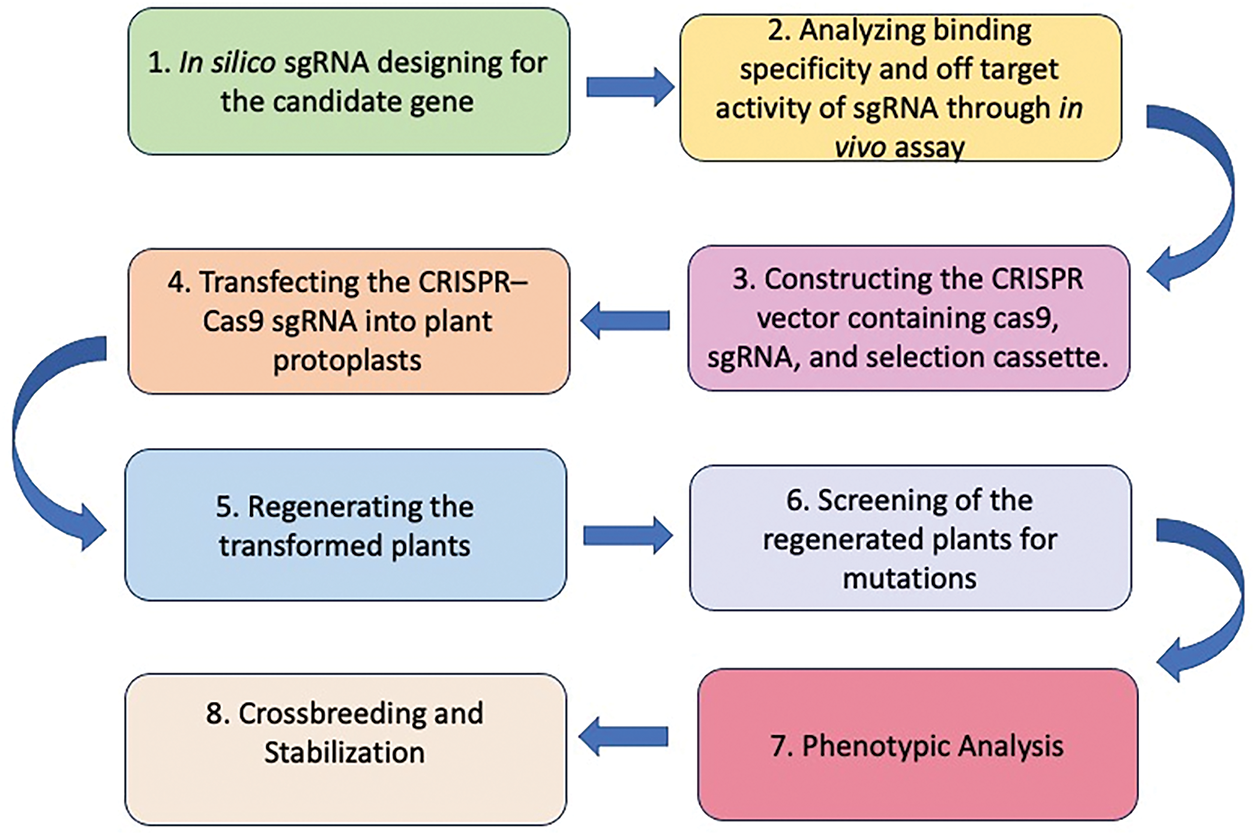

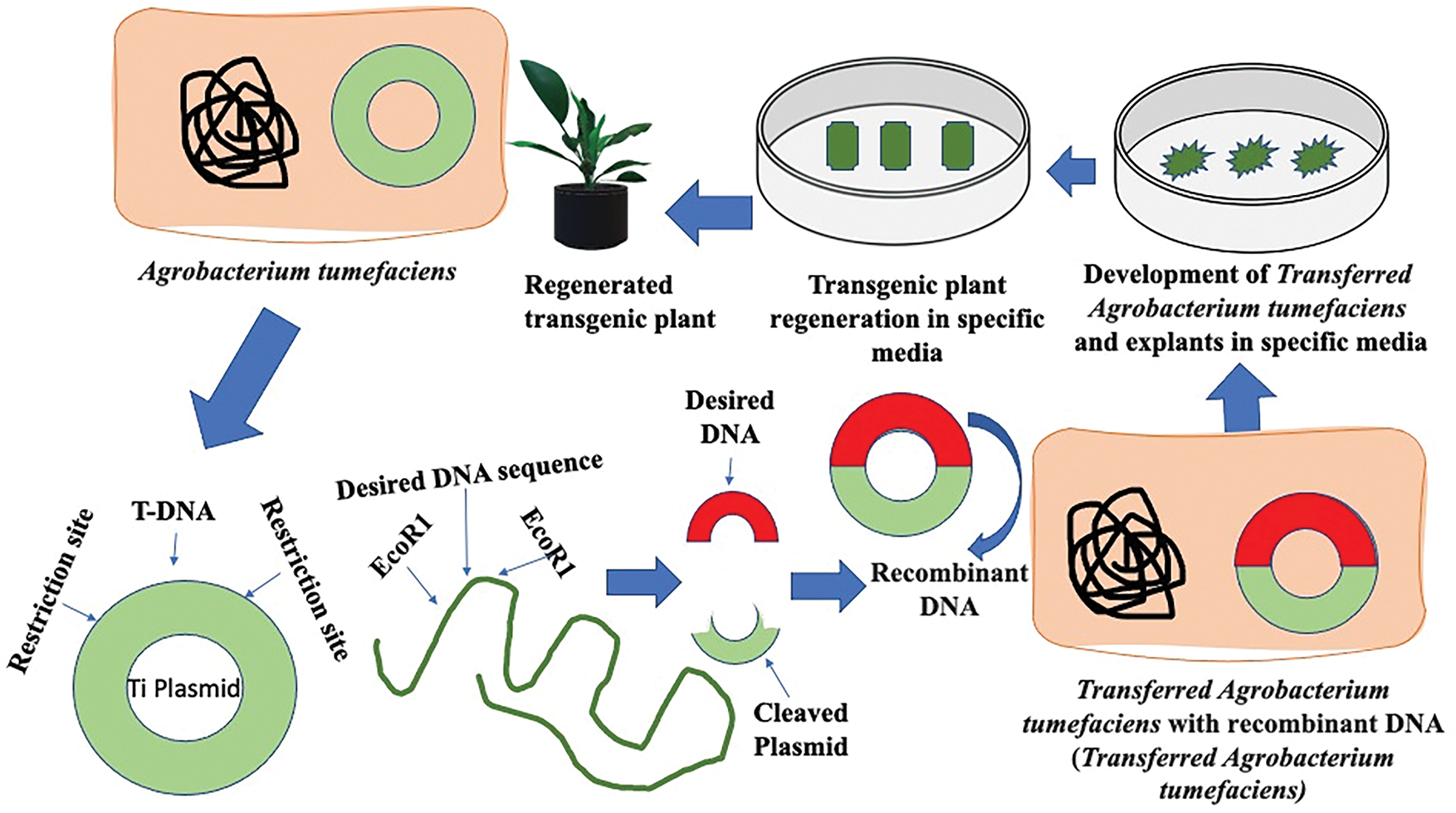

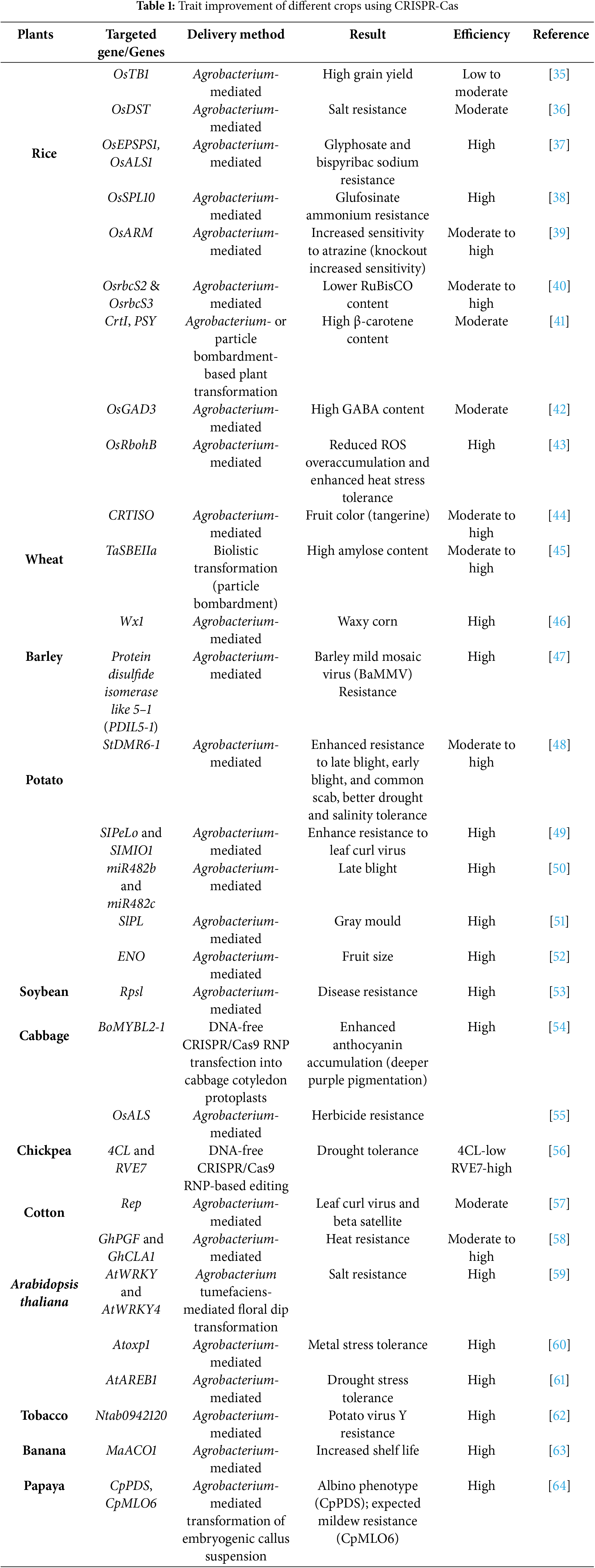

The use of Cas9 requires the presence of a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence positioned near and directly aligned with the target site. To ensure effective targeting, different spacer sequences are essential. Due to these characteristics, CRISPR/Cas9 is widely recognized for its speed, efficiency, affordability, and versatility [25]. The key steps in CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing for crop trait improvement are illustrated (Fig. 3). CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome editing has been employed to improve traits such as yield, stress resilience, and disease resistance in key crops including rice, wheat, maize, and potato (Table 1).

Figure 3: Steps of CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing for trait improvement of crops

CRISPR/Cas9 has revolutionized genome editing, but it is not without its drawbacks. A major challenge remains the occurrence of off-target effects, in which unintended genomic regions are inadvertently modified. Unintentional cleavage and alterations at untargeted genomic regions that have a similar but distinct sequence from the target site are known as off-target effects [29]. Why the Cas9 protein cleaves some off-target sites but not others is a mystery. Since it has been demonstrated that Cas9 cleaves more effectively in open chromatin regions, chromatin shape may be a significant factor influencing Cas9 cleavage [30,31]. Because polyploidic plants may produce homoeoalleles that are very close with only one nucleotide mismatch, the ploidy level may have a greater impact on the occurrence of off-target effects. Modifying one of these sequences could make it more likely that off-target impacts will be discovered [32]. But since the goal is frequently to alter all homoeoalleles, investigators can search for the desired off-target cutting [33,34]. Additionally, the efficient delivery of CRISPR components into plant cells remains a technical challenge, especially for transformation-resistant species. The commercialization of genome-edited crops is questioned due to national governmental constraints as well as technical challenges. Ethical concerns also arise, particularly with regard to food safety, public perception, and unknown ecological consequences. These problems need to be fixed if CRISPR technology is to be applied successfully and responsibly in agriculture.

3 Marker-Assisted Selection (MAS)

The gradual increase in the world’s population stresses the food demand, which has unveiled the necessity to develop improved cultivars with particular traits in a short period [65]. In conventional breeding, hundreds and even thousands of plant populations are grown [66]. Handling such a giant population is less effective and time-consuming. That’s why the usefulness of new approaches is required to help plant breeders [67]. Marker-Assisted Selection (MAS) is the process of manipulating genomic areas that are engaged in the expression of desirable traits with the help of DNA markers [19]. MAS facilitates the phenotypic selection using markers in such a way that is effective, credible, and cost-efficient, making this process superior to traditional plant breeding [68]. A correlation between traits of interest and molecular marker(s) is required for MAS, which can be achieved through phenotyping of the genetic mapping population, followed by Quantitative Trait Loci (QTL) mapping [69].

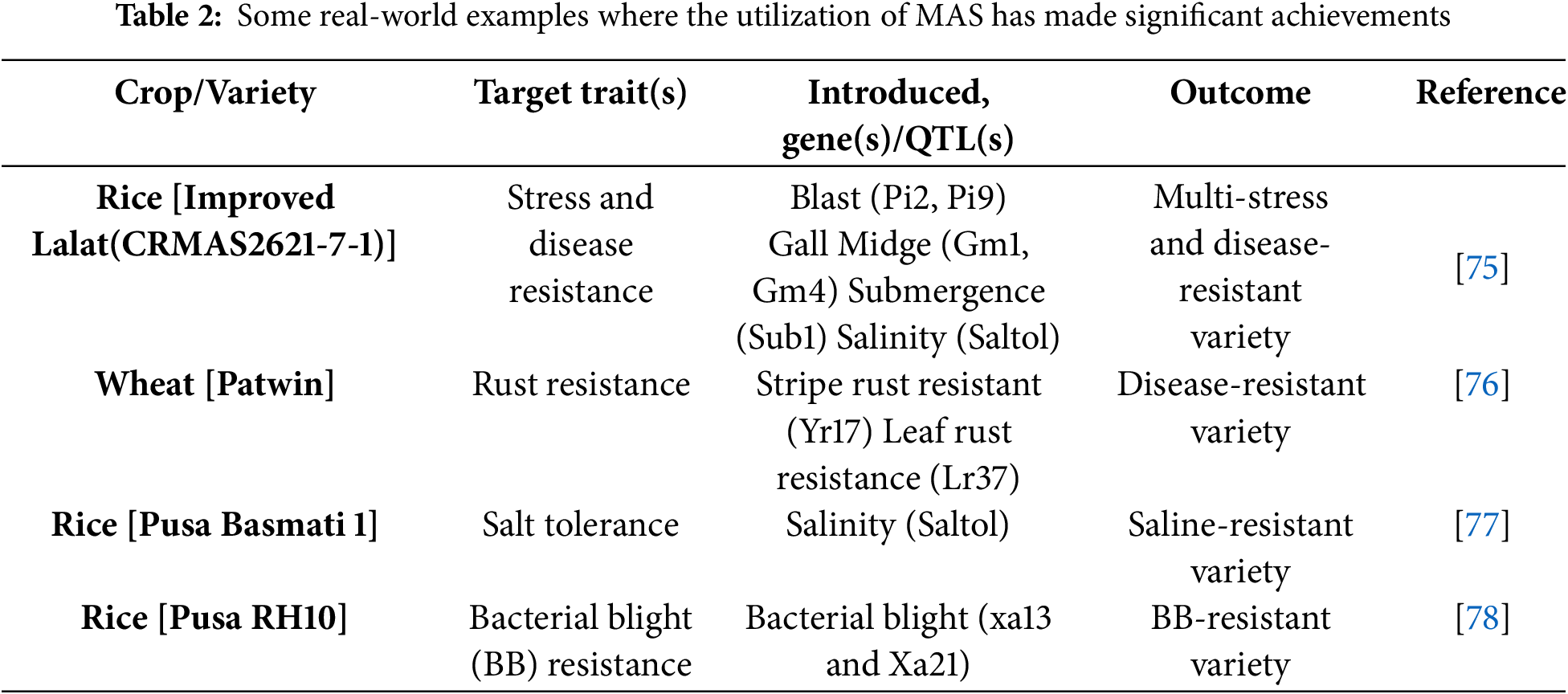

Molecular markers are a particular sequence of DNA that can be identified and used to detect changes among individuals. An ideal molecular marker should possess many features: 1. Polymorphic and uniform distribution throughout the genome; 2. Simple, fast, and not expensive; 3. Stable and identifiable across the tissues; 4. Do not have environmental, pleiotropic, and epistatic influence [70]. Genetic markers are grouped into 2 classes: One is classical markers, and the other is molecular/DNA markers, where classical markers are further classified into morphological, biochemical, cytological and Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP), Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism (AFLP), Simple Sequence Repeats (SSRs), Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) and Diversity Arrays Technology (DArT) markers are examples of molecular markers [71]. RAPD markers are achieved through random amplification of genomic DNA with the help of short primers. It is also known as a universal primer. The major drawback of RAPD is low reproducibility [70]. AFLP covers the whole genome, dominant/codominant, polymorphic level is high. The limitation of low reproducibility in RAPD can be overcome using AFLP [16]. SSRs are tandem repeats of 1 to 6 ling nucleotide DNA motifs. It has a codominant nature, relative abundance, and chromosome-specific location, which can be directly derived from a genomic DNA library [72]. Markers that are gained through single-nucleotide substitution, known as SNPs. Prior genetic information is not required for these types of markers [71,73]. DArT is a hybridization-based microarray molecular marker that can work sequence-independently and is cheap to use, but brings fast results [74]. Table 2 shows some key improvements in crops through MAS.

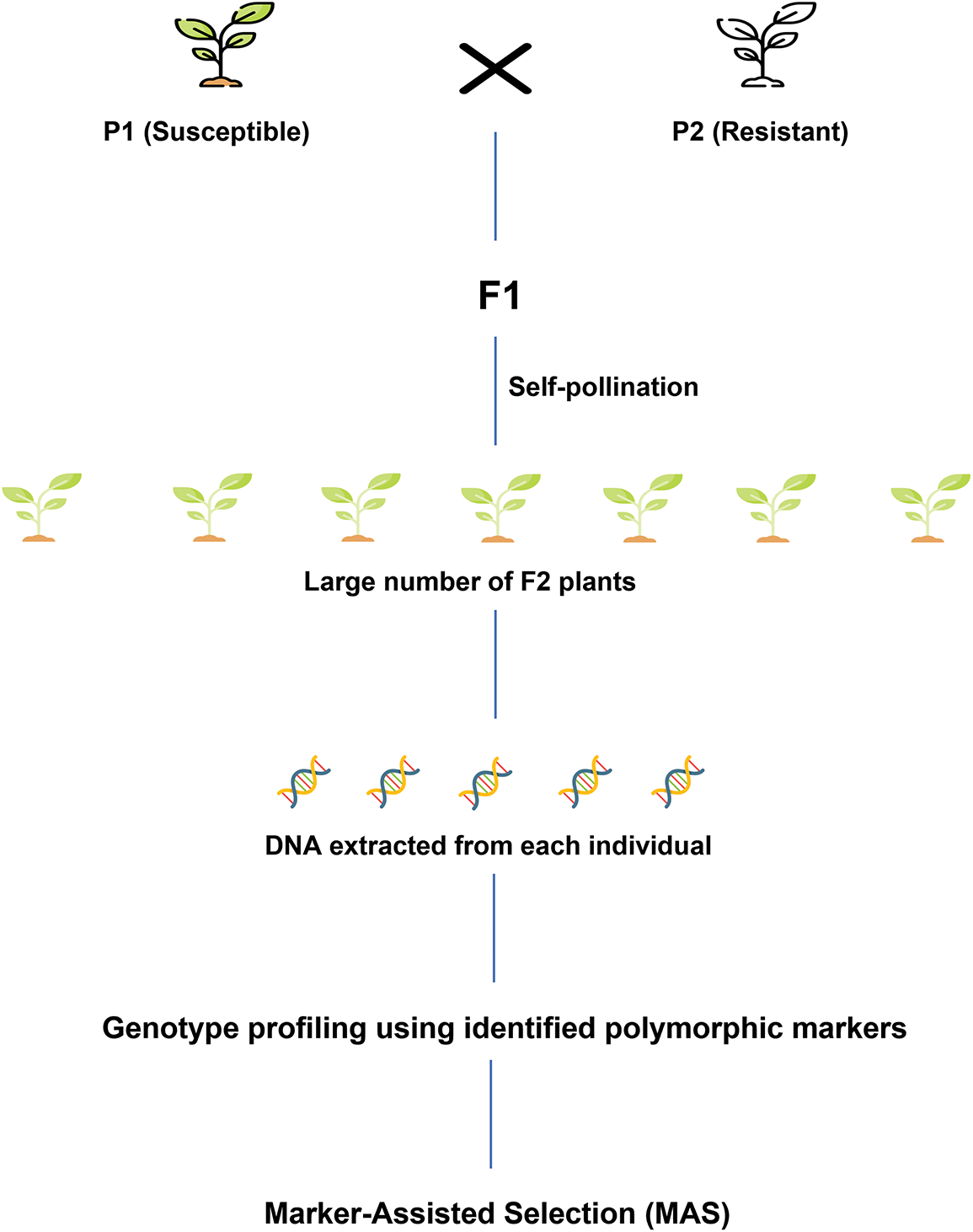

In MAS, the selection of parental lines is crucial, which is often overlooked by plant breeders. The selection process is done among outstanding lines to improve a target trait by crossing with a tester [19]. For performing MAS, QTL (Quantitative Trait Locus) mapping should be constructed, which includes the development of a mapping population, identification of polymorphic markers, and linkage analysis of markers [68]. MAS follows several steps, which are represented visually (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: General pipeline for MAS (modified after [16])

3.2 Advantages and Challenges of MAS

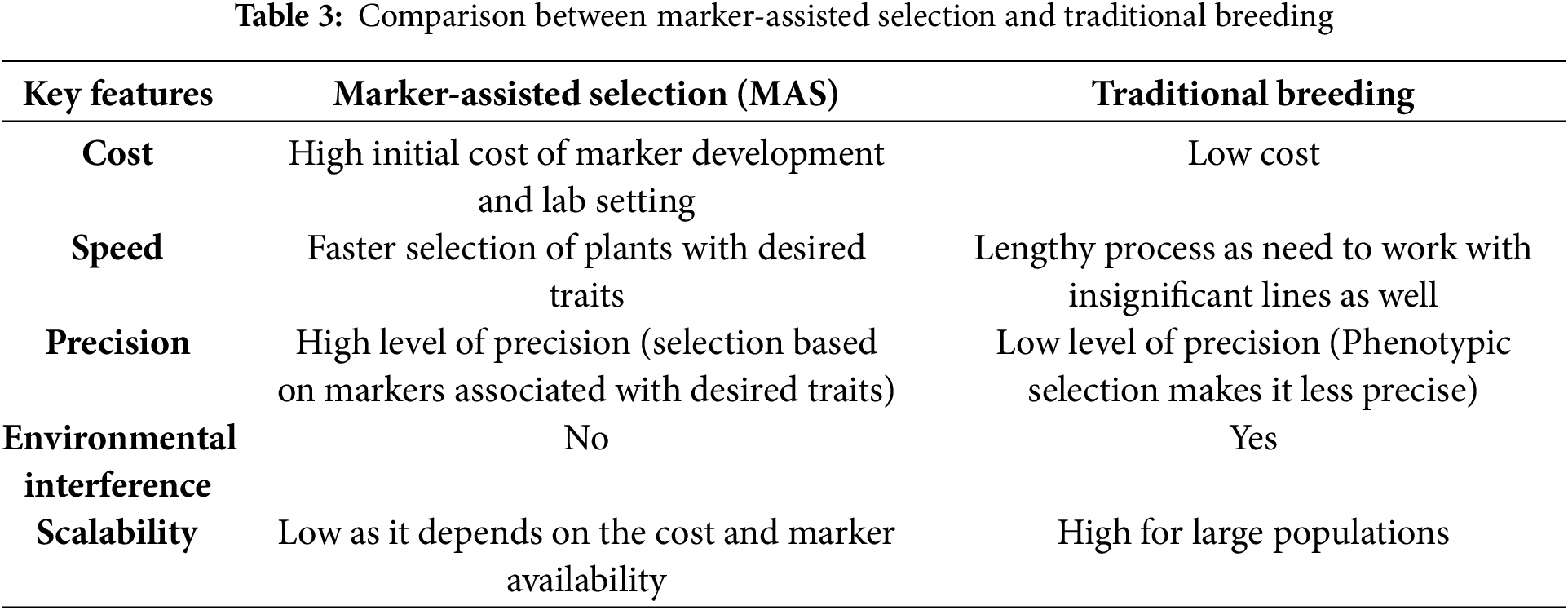

Conventional plant breeding largely relies on phenotypic selection, having a risk of missing important traits and delaying the process of varietal development, whereas MAS offers an effective, alternative, inexpensive, faster, and precise selection efficiency by speeding up the breeding cycle [65,79]. This method has the superiority of eliminating the insignificant lines quickly, facilitating breeders to focus only on promising materials [67]. Moreover, MAS is a very credible plant breeding approach when desired traits are of low heritability, recessive in nature, and gene pyramiding is desired [80]. It is a very powerful method for assessing the genetic variability and diversity among the genotypes [81]. In MAS, the detection of heterotic groups is possible using DNA markers, and this breeding method does not rely on the environment, making it possible to assess resistance against biotic and abiotic impediments throughout the year [79]. Many varieties that have been released with the blessing of MAS, such as rice, maize, wheat, etc., where specific traits were improved, for example, disease resistance, higher yield, etc. [65]. However, this process has some drawbacks too. Most of the molecular markers are not readily available to use in plant breeding due to their unavailability and expense on a broad scale [82]. The initial cost of marker development and implementation is high, especially for the improvement of complex traits [83]. Changing the attitude of plant breeders for utilizing MAS is also crucial, as breeders in many parts still rely heavily on phenotypic selection [84]. One of the major constraints of MAS is the detection of QTL, which regulates desired traits, as well as there is probability of double-crossovers between markers, which can result in losing the target QTL [85]. Studying QTL using the process of MAS is a very tedious job because it has cumulative effects, which can be controlled by environmental conditions and genetic constitution [16]. Key contrasts between MAS and traditional breeding are shown in Table 3.

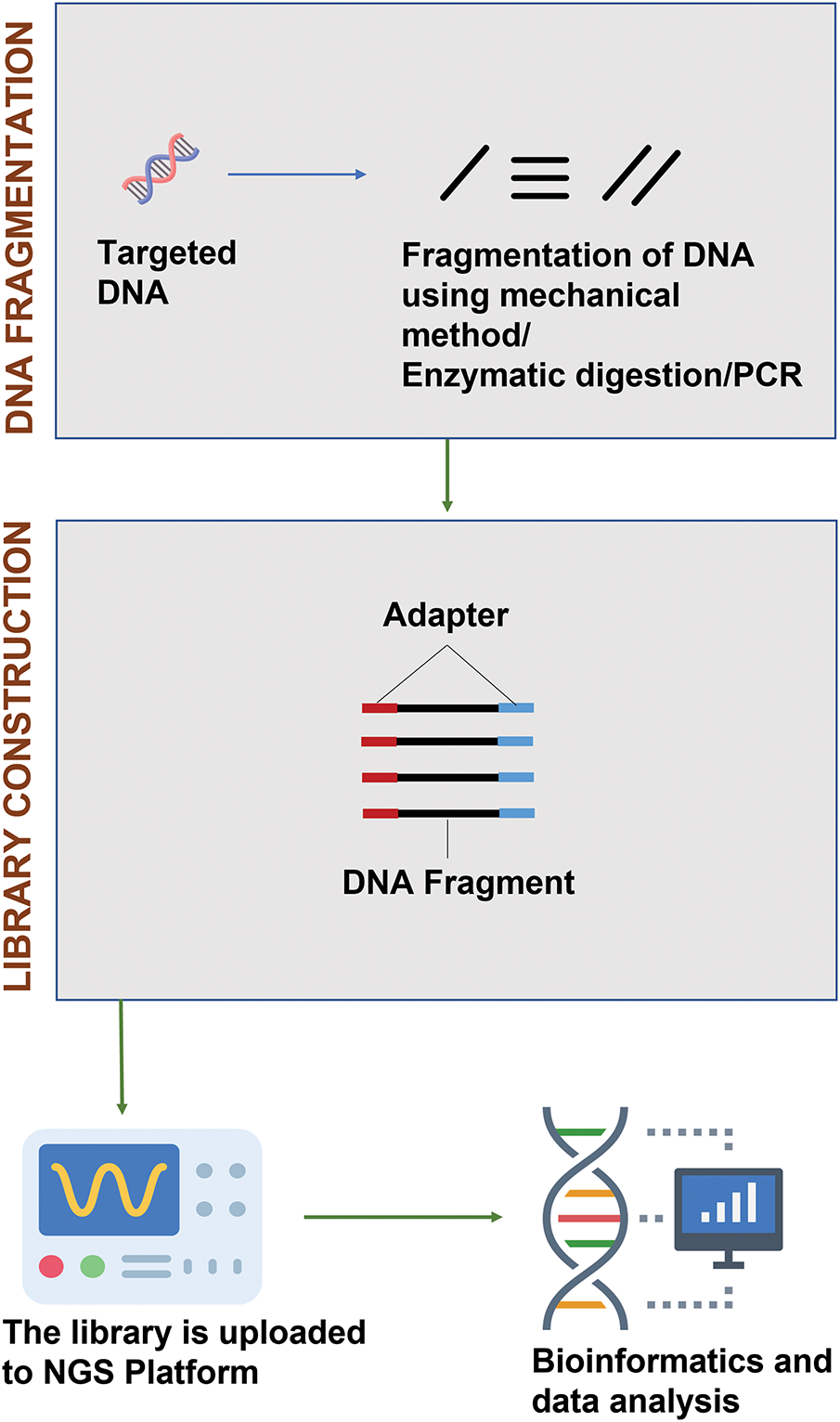

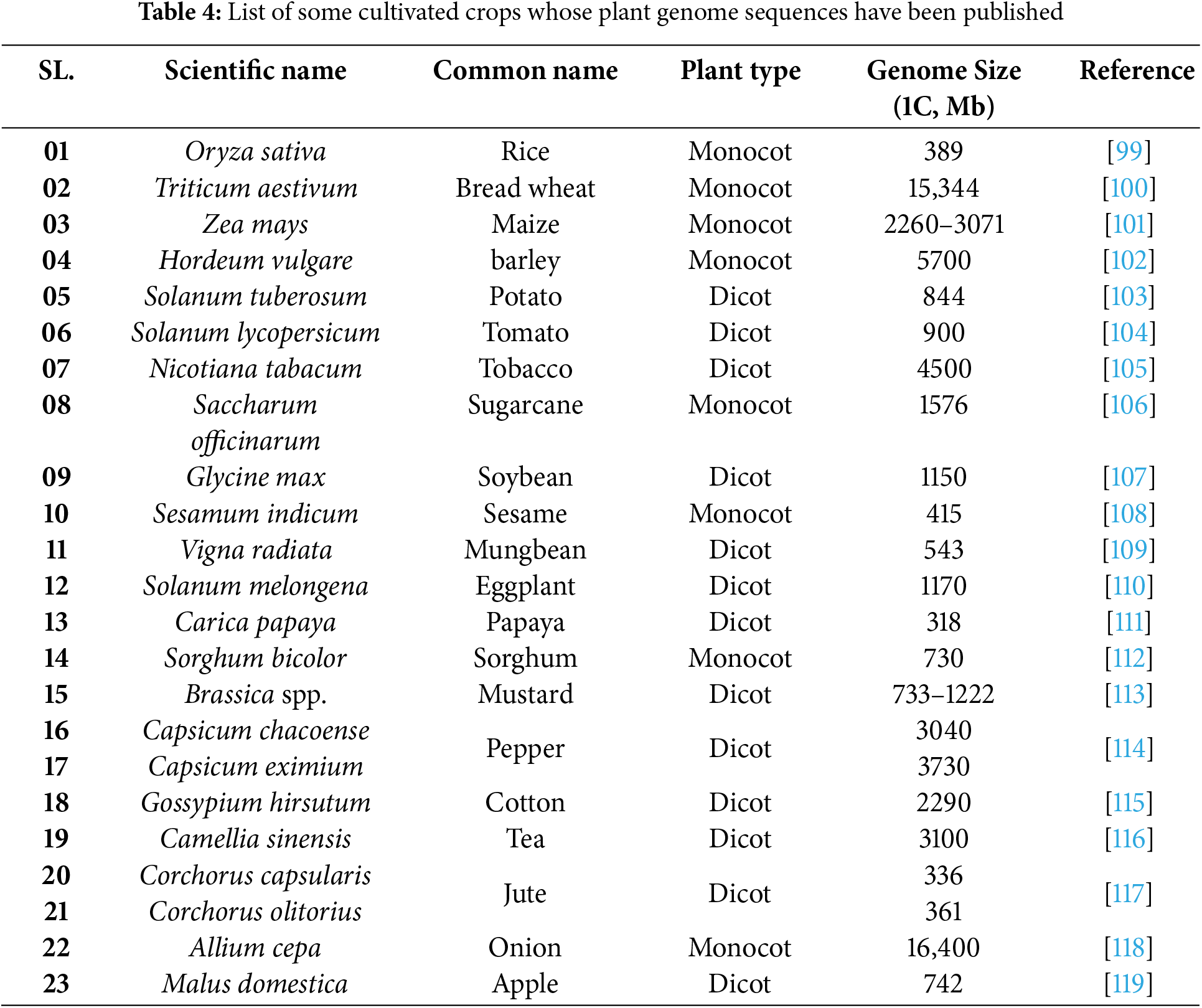

Each phase of a living creature’s lifecycle is regulated by its DNA constitution [86]. To understand a crop’s heritable traits, understanding its genome is crucial to correlate the variation of the genome with desired agronomic traits, which assist the crop improvement program [87]. Moreover, whole-genome sequencing provides information related to plant physiology [88], accelerates the genetic diversity of breeding activities [89] as well as help to detect genetic variation among the population, which becomes effective in ecological and environmental studies of plants [90]. Genome sequencing is a crucial method of determining the nature and site of gene editing, which has opened the door to innovating climate-resilient crop varieties to ensure sustainable production [91]. The Sanger sequencing method was applied initially for genome sequencing, which is known as first-generation sequencing [92]. Due to several drawbacks such as high cost, low throughput, and labor intensity, next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology, also called second-generation sequencing, was discovered [86]. Advanced genome sequencing methods can generate giant data, which can be utilized to identify important agronomic traits such as fruit size and color, flowering time, quality management of crop, etc. [93]. Sequencing of the whole genome can be obtained through NGS, and those sequence data not only help to study variation at the gene level but also facilitate the determination of evolutionary relationships among crop plants [94]. NGS produces a large amount of genomics data, which facilitates the investigation of complex traits in plants like salt tolerance [95]. High-quality mapping and candidate gene detection have become possible using NGS technology [96]. NGS follows 2 approaches: sequencing by synthesis and sequencing by ligation, which are performed through NGS platforms such as 454 pyrosequencing, Illumina Solexa, Ion Torrent, and ABI SOLiD sequencing [91]. Among them, Illumina and SOLiD platforms are the winner regarding cost savings due to their low cost per megabase (Mb) of sequence. However, it is worth mentioning that no single platform can achieve all the necessities of users at a time [97]. According to Qin [98], NGS platforms follow several steps for sequencing, which are illustrated (Fig. 5) below:

Figure 5: General steps involved in NGS

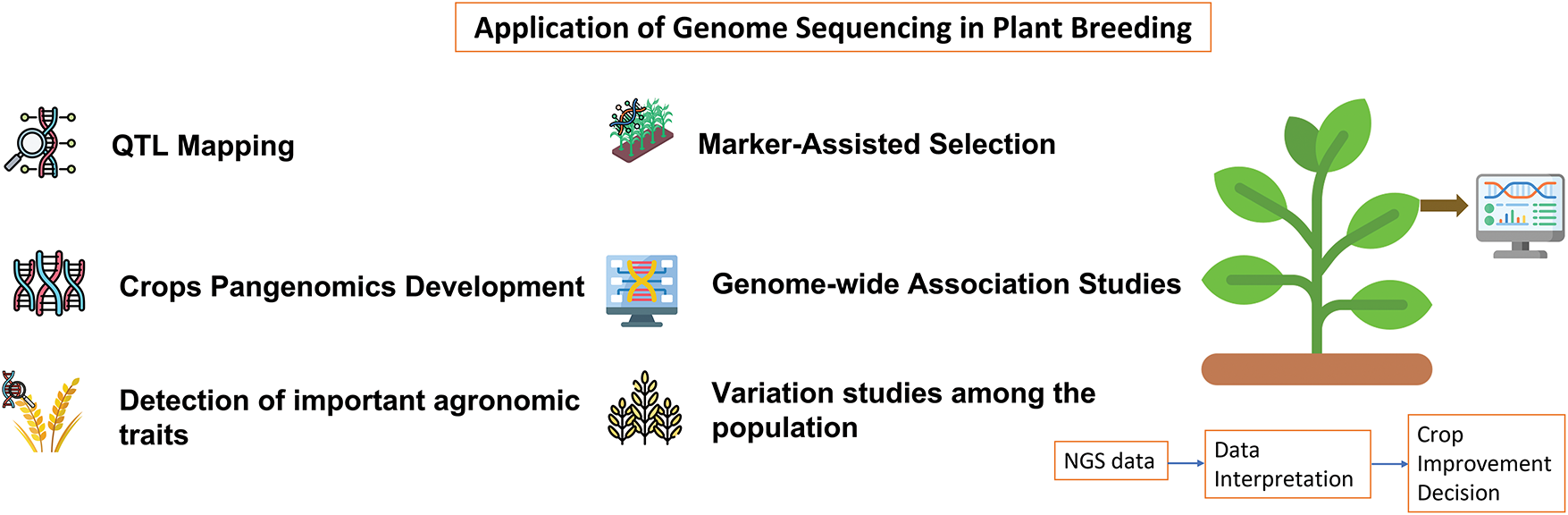

Genome sequencing has been successfully utilized in crop breeding programs by identifying protein-coding and non-protein-coding regions, and serves as a fundamental tool for mapping QTL and studying genomics (Fig. 6) [94].

Figure 6: Genome sequencing application in crop breeding

Development of the climate-resilient varieties, including rice, oilseed and pulses, fruits, and horticultural crops, has become possible through the advancement of genome sequencing technologies, which can withstand biotic and abiotic stresses (Table 4) [91].

5 RNA Interference (RNAi) of Target Genes in Plants

Agricultural productivity is severely affected by biotic stresses such as insects, nematodes, parasitic weeds, and pathogens, including viruses, bacteria, and fungi, which pose major threats to crop yields, with viruses and pests causing particularly severe losses in plant productivity. Conventional breeding methods have enhanced both the quality and yield of crops and the development of disease-resistant and stress-tolerant cultivars; however, these approaches are time-consuming, labour-intensive, and constrained by the limited availability of genetic resources for many crops [23]. To address these problems, it is essential to integrate modern breeding techniques, molecular genetics, recombinant DNA technology, and biotechnological approaches to grow high-yielding crop varieties with enhanced resistance to diseases and environmental stresses [80]. Furthermore, the emergence of newly developed virulent microbes capable of overcoming resistant cultivars underscores the urgent need for innovative strategies to combat these highly adaptable crop pests. To overcome these challenges, RNA silencing or RNA interference (RNAi) technology has played a vital role as it is a biological process that induces ‘post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS)’, triggered by ‘double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)’ molecules, to suppress the expression of specific target genes [120,121]. RNAi technology has been successfully employed to enhance a range of desirable traits, including the reduction of toxic or allergenic compounds, induction of morphological changes, modification of male sterility and self-incompatibility, enhancement of secondary metabolite production under stress conditions, and improvement of plant resilience to various abiotic stresses (Fig. 7) [122].

Figure 7: Application of RNAi in plant breeding

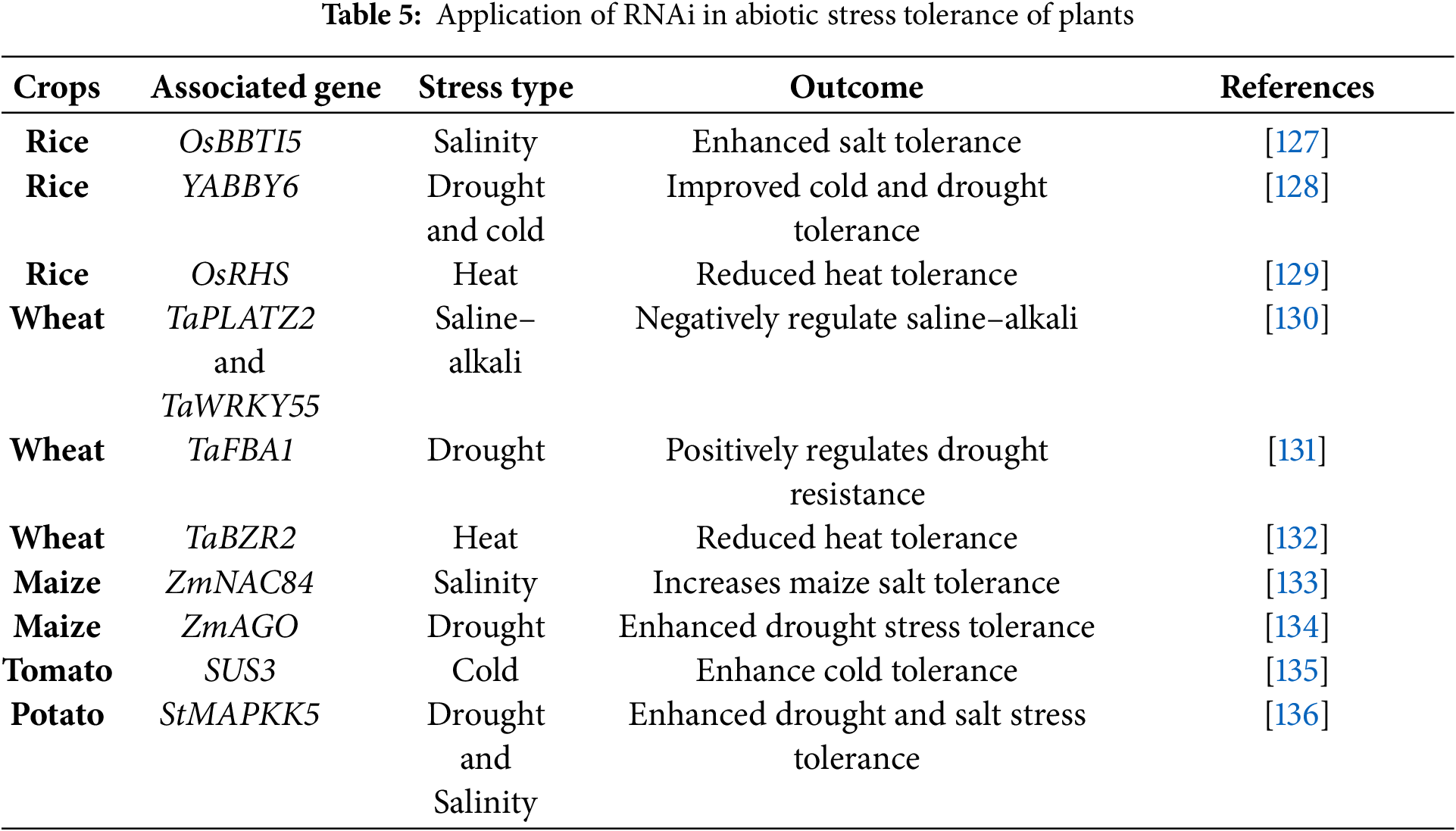

5.1 RNA Interference (RNAi) for Abiotic Stress Tolerance

Abiotic stress is becoming a serious concern for living organisms. Abiotic stresses adversely affect plant growth and development by causing direct or indirect disruptions to physiological and developmental processes [123]. A substantial portion of agricultural land is affected by abiotic stresses that can markedly diminish crop productivity and yield [124]. Traditional breeding approaches aimed at enhancing abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants have achieved only limited success to date [125]. Meanwhile, RNAi offers a precise approach for the targeted down-regulation of particular genes without interfering with the expression of unrelated genes in the plants [126]. Thus, this technology plays a crucial role in opening new avenues for researchers to address global environmental challenges and develop climate-resilient crop cultivars to ensure food security. Some effects of using RNAi technology in plants to develop abiotic stress-tolerant varieties are illustrated in Table 5.

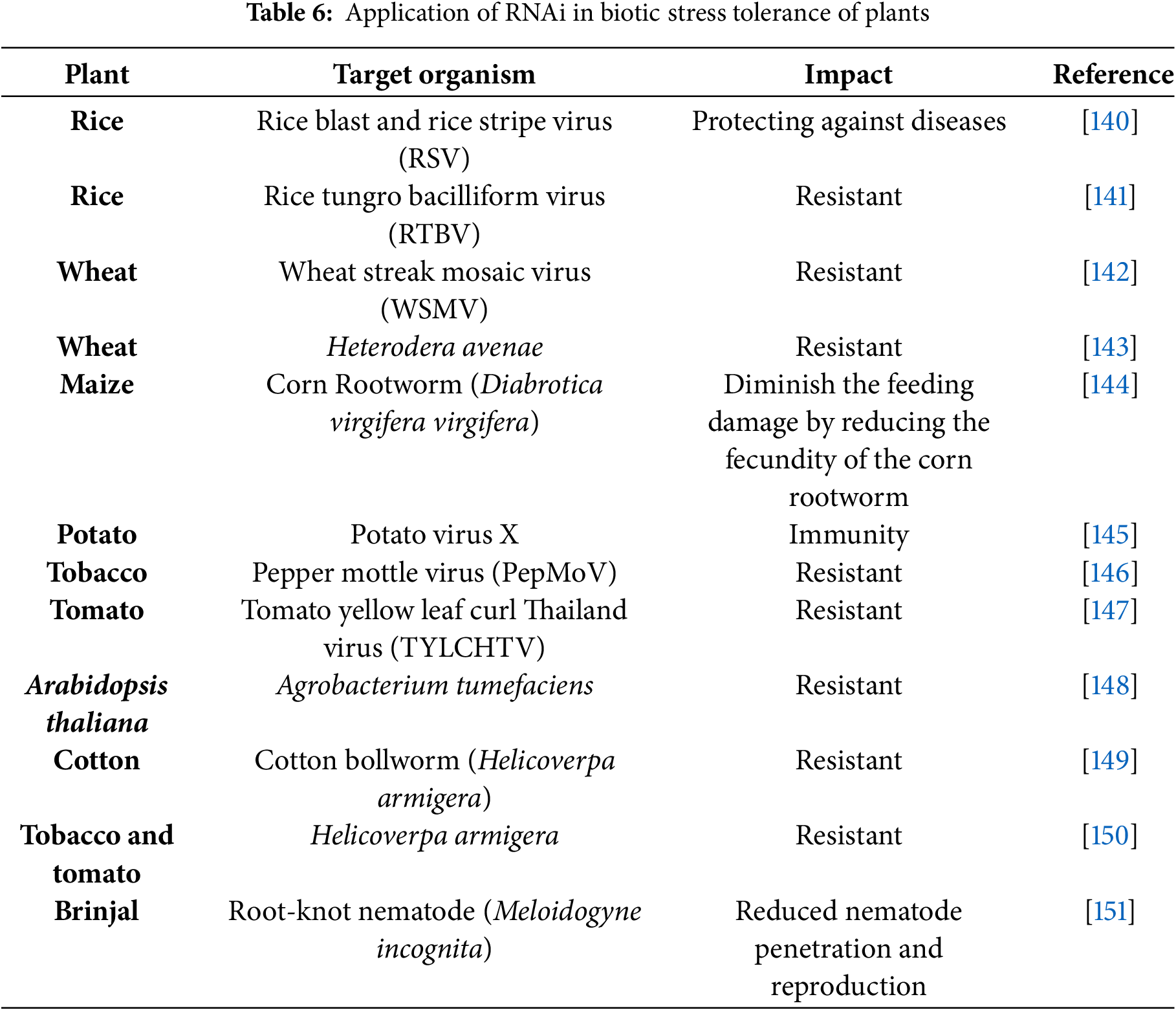

5.2 RNA Interference (RNAi) for Biotic Stress Tolerance

Over time, conventional breeders have developed many disease- and pest-resistant crop varieties, but this approach is time-consuming, tedious, and a complex process. Application of pesticide or insecticide is not only hazardous to human health but also exerts detrimental effects on the environment [137]. Researchers have employed various strategies to develop pathogen-resistant cultivars, but over the past decade, RNA interference (RNAi)-induced gene silencing has arisen as a promising and effective tool for engineering pathogen-resistant plants [138]. This approach has paved the way for eco-friendly strategies in plant improvement by enabling the targeted suppression of stress-inducing genes and promoting the expression of genes associated with disease resistance [139]. Development of disease-resistant plants by using RNAi technology is summarized in Table 6.

Plants that have had their DNA modified using genetic engineering techniques are called transgenic plants. The purpose of this modification is to introduce a trait that is not naturally found in that plant species. These plants contain one or more genes that have been deliberately inserted. The inserted gene, known as a transgene, may come from a different species entirely or from an unrelated plant [152].

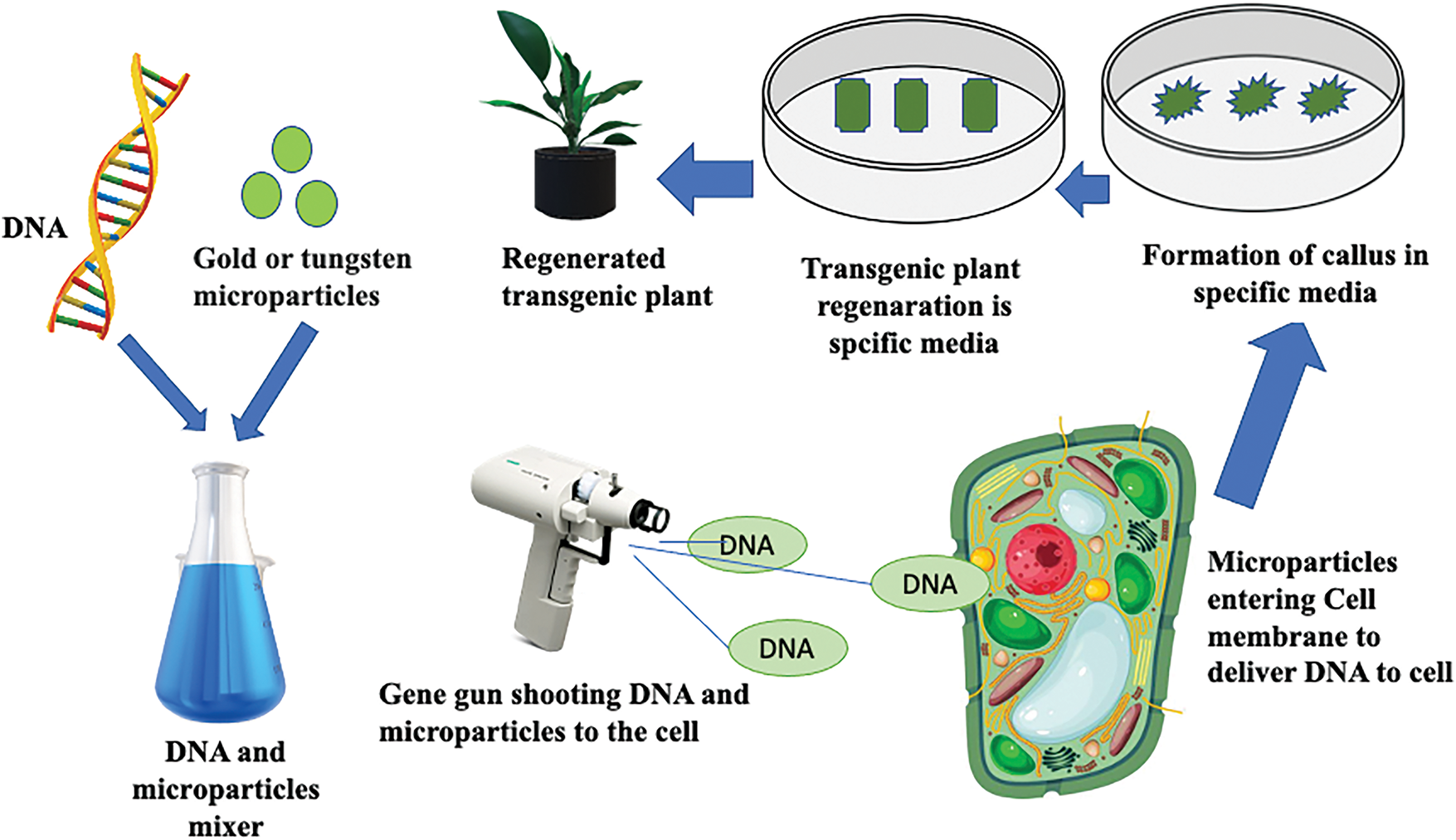

The earliest transgenic plant developed was a tobacco plant engineered to carry antibiotic resistance, achieved in 1982. A few years later, in 1986, herbicide-resistant tobacco plants were tested in field trials in both the United States and France. Following these advancements, Calgene introduced the Flavr Savr™ tomato in 1994-marking it as the first genetically modified food crop to be commercially produced and consumed in an industrialized nation [153]. Genetically modified plants are created using methods like Agrobacterium-based transformation or other techniques that directly transfer DNA. Genes offering traits such as insect resistance, disease protection, and herbicide tolerance have been successfully incorporated into crops using genetic material from diverse plant and bacterial origins [154]. Genetically modified crops are typically produced using two main techniques [153]:

1. The gene gun method, where the target gene is attached to tiny gold or tungsten particles and then physically propelled into plant cells, allowing the DNA to integrate into the plant’s genome (Fig. 8).

2. The Agrobacterium tumefaciens method, which uses a bacterium naturally capable of transferring a segment of its DNA-engineered to carry the desired gene-into the DNA of the host plant (Fig. 9).

Figure 8: Transgenic plant formation using the gene gun method (modified after [155])

Figure 9: Agrobacterium-mediated transgenic plant formation (modified after [155])

Genetic transformation has become one of the most important techniques for studying plant genomes. It is now widely used in gene discovery and in exploring the functions and regulatory mechanisms of genes in plants [156].

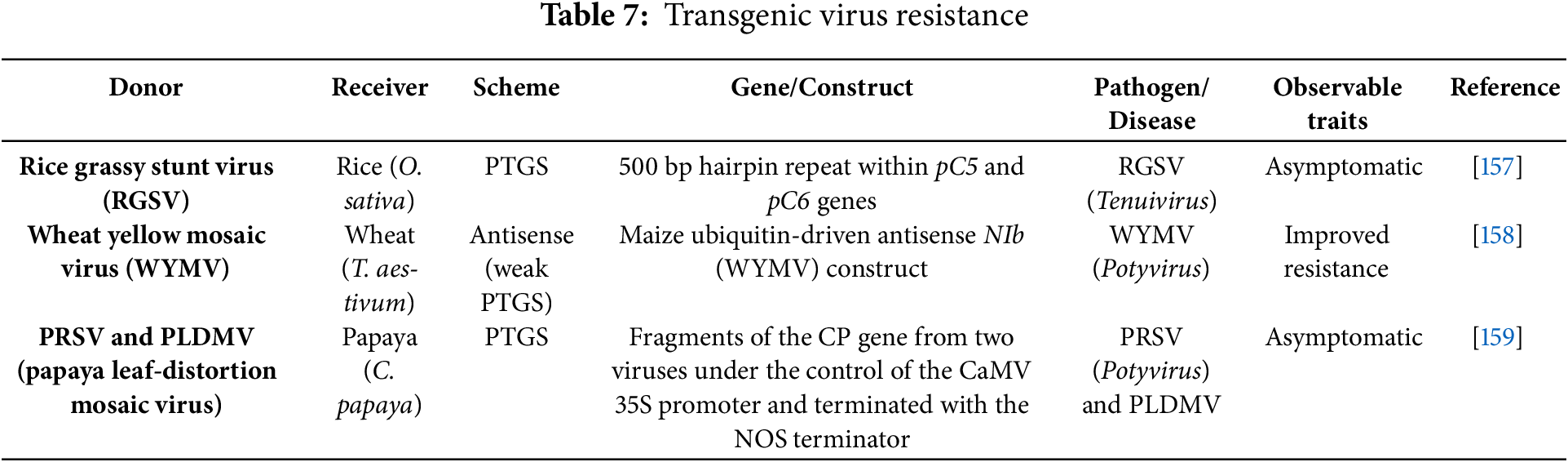

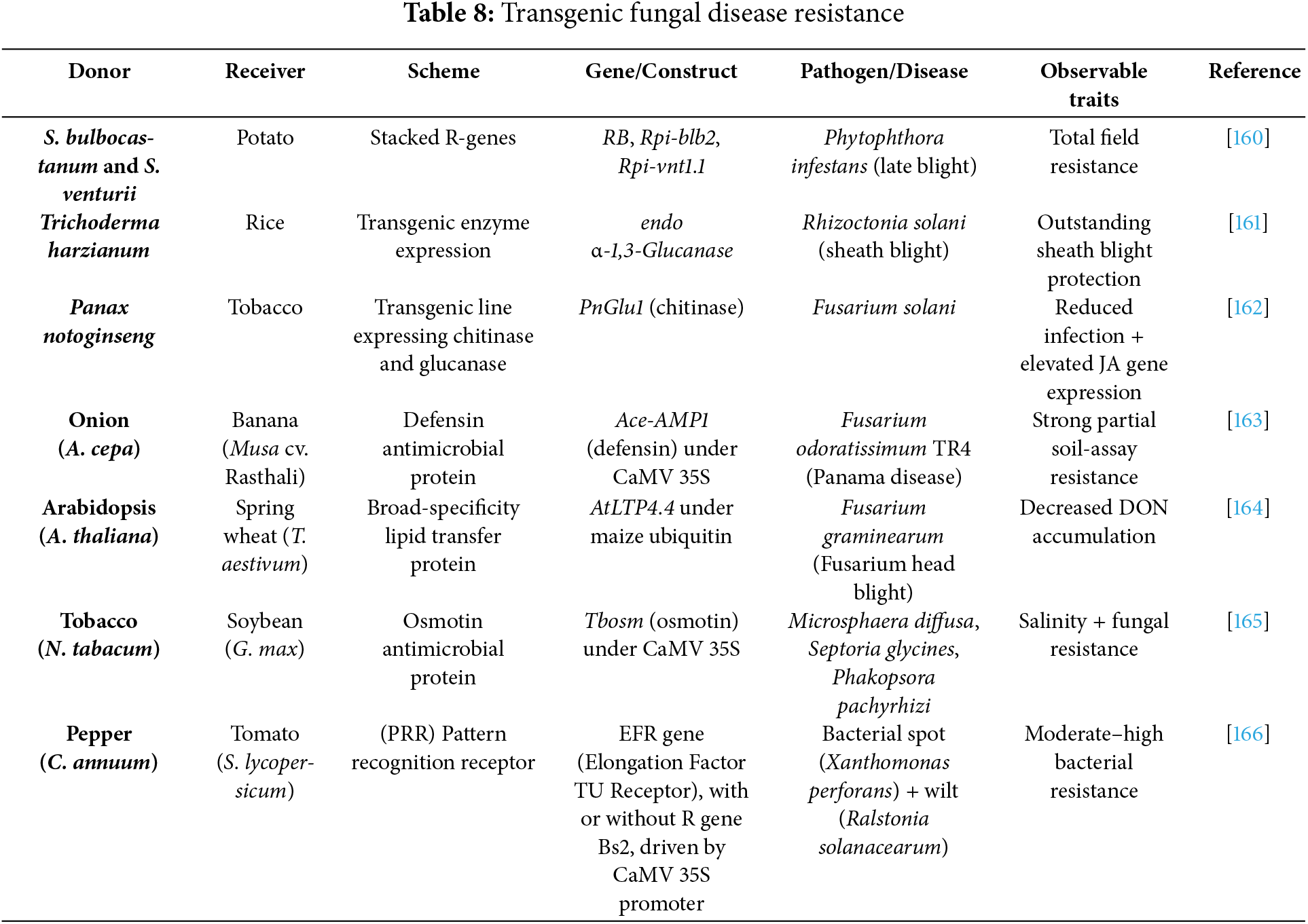

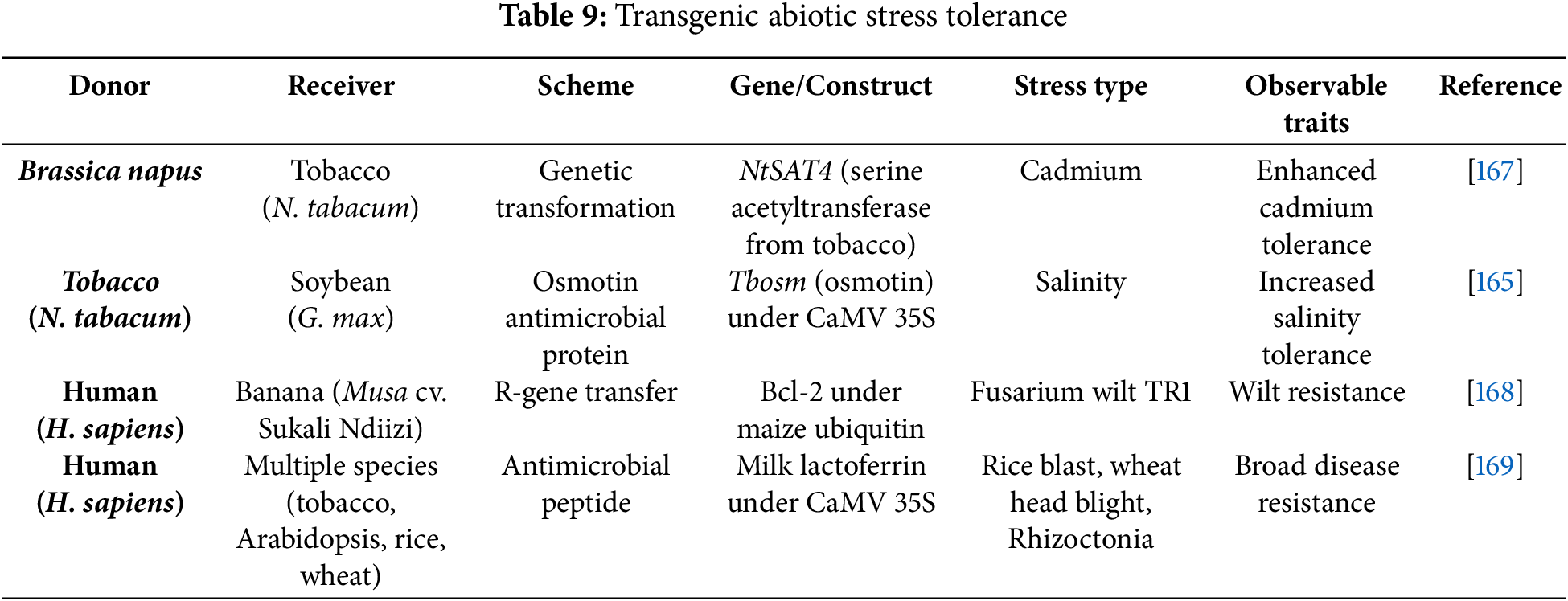

Introducing a set of genes into a plant aims to enhance its usefulness and productivity. This genetic modification offers several benefits, including extended shelf life, increased yield, better quality, resistance to pests, and the ability to withstand various environmental stresses such as extreme temperatures, drought, and diseases [152]. A range of transgenic plants has been developed using targeted genes or genetic constructs to improve traits like disease resistance and increased yield potential (Tables 7–9).

7 High-Throughput Phenotyping (HTP)

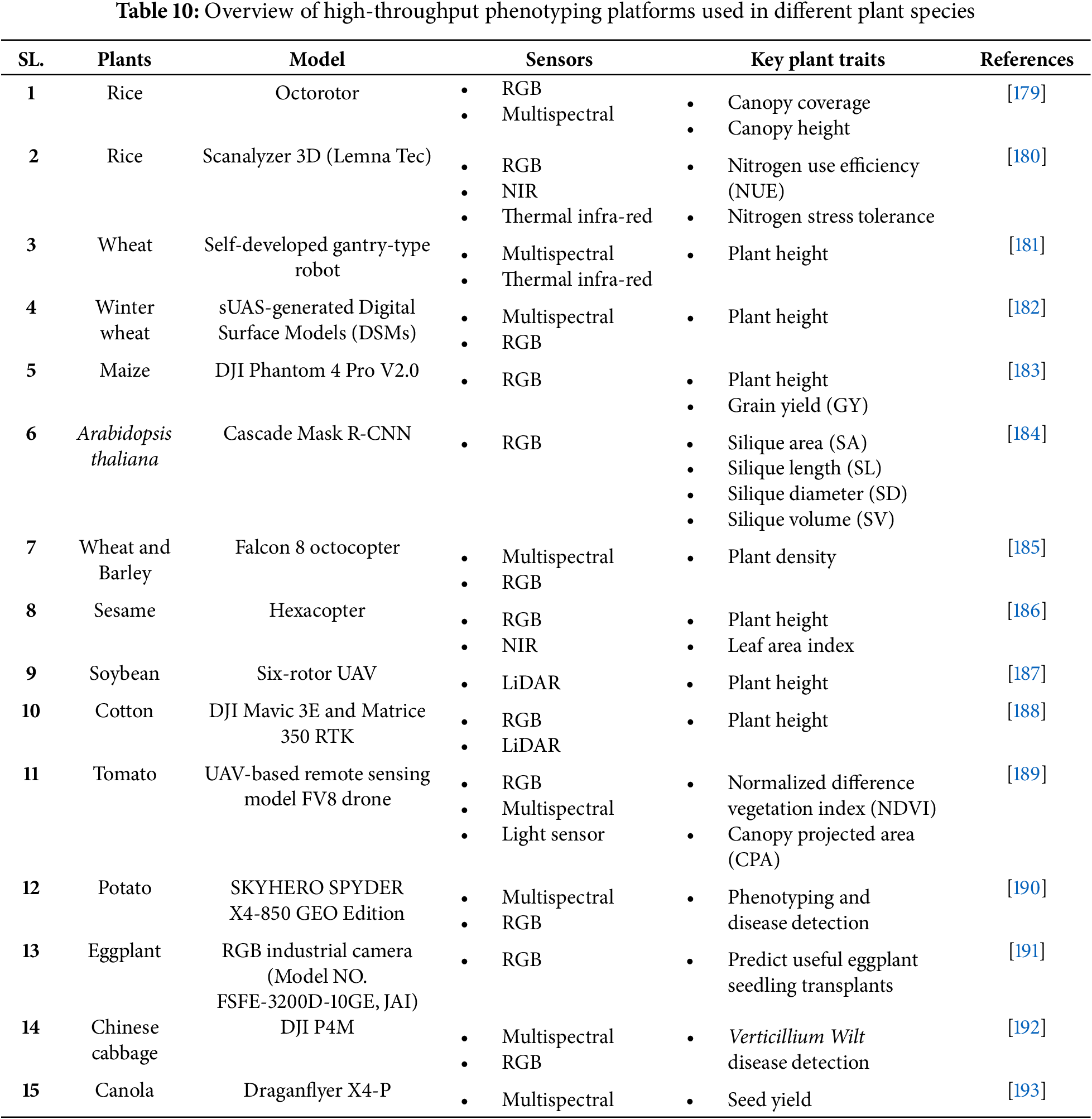

The Plant phenotype is established during its growth and development through the dynamic and complex interaction between its genetic composition and the environmental conditions in which it grows [170]. Traditional breeders rely on artificial phenotyping, screening crop traits through visual inspection, taste, and by touching it, which is time-consuming, laborious, often destructive, and requires substantial human resources to evaluate large crop populations [171]. Additionally, conventional phenotyping techniques pose challenges in accurately identifying biochemical and physiological traits [172]. To overcome this limitation, various phenotyping platforms have been developed over the years, enabling more precise and comprehensive analysis. The high-throughput phenotyping (HTP) integrates non-destructive and quick techniques that can rapidly phenotype large plant populations and enhance selection efficiency, to optimize breeding programs for developing improved cultivars [173]. High-throughput phenotyping (HTP) platforms use numerous optical sensors to record changes in plant characteristics, including physiological, morphological, and biochemical variations [174]. These sensors respond uniquely to plant surfaces and use visible light (RGB), hyperspectral, thermal, light detection and ranging (LiDAR), and fluorescence to monitor and analyze nondestructive traits [175]. Furthermore, combining machine learning (ML) with artificial intelligence (AI) has significantly improved the accuracy and efficacy of phenotyping data [176]. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are deep learning models that have shown remarkable accuracy (up to 99.92%) in classifying plant species and predicting growth stages, including the identification of Arabidopsis lines [177]. The VGG16, CNN, and MobileNet models utilize deep learning techniques to identify a range of plant diseases accurately [178]. Therefore, the incorporation of high-throughput phenotyping with breeding programs facilitates the identification of improved agronomic traits, which can be utilized for future advancements in crop improvement. Table 10 represents the application of high-throughput phenotyping (HTP) in the development of key crop traits, along with the specific model employed.

8 Role of Mutagens in Molecular Breeding

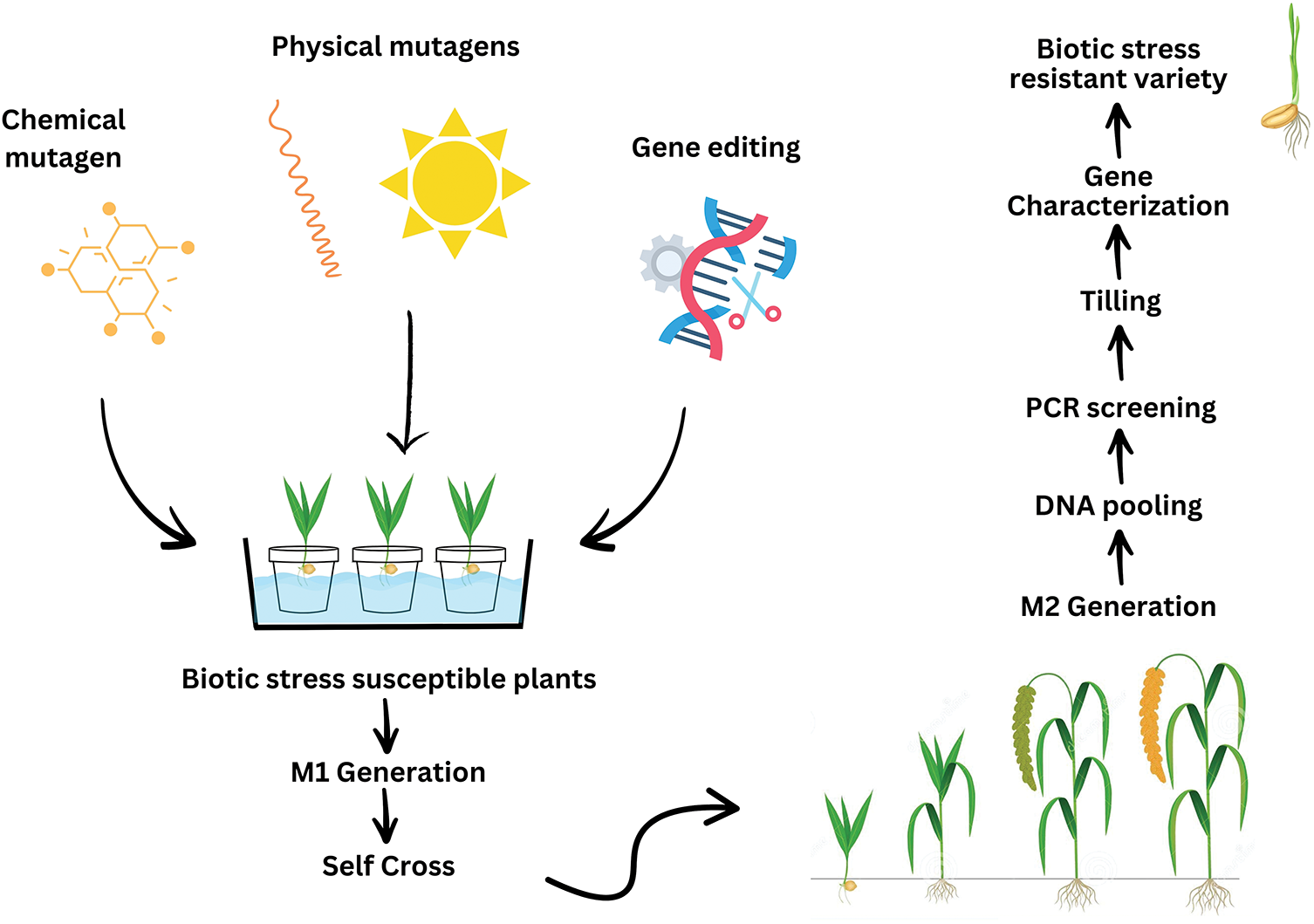

Mutation refers to a sudden, heritable alteration in the DNA in a living organism’s cell that does not result from genetic segregation or recombination. Mutation breeding is the deliberate induction and utilization of such mutations to develop improved crop varieties [194]. Mutation breeding plays a vital role in crop improvement and complements the advancements achieved through conventional plant breeding methods [195]. It serves as an effective tool for understanding genetic phenomena like genetic advance, inheritance, coefficient variability of genotype and phenotype, as well as mutagenic efficiency and effectiveness [196]. The foundation of mutation breeding for crop improvement was laid in the 1920s when John Stadler first discovered the mutagenic effects of X-rays on plants [197]. In 1942, the first X-ray-induced, disease-resistant mutant was reported in barley [198]. Mutant varieties can be developed to address nearly all breeding objectives, including improvements in yield, plant stature, quality, disease and pest resistance, abiotic stress tolerance, postharvest stability, and the introduction of novel consumer-oriented characteristics [199].

In mutation breeding, seeds directly exposed to a mutagen (physical or chemical) are referred to as the M0 generation, which, after germination, develop into M1 plants [200]. Subsequently, self-fertilization occurs within the M1 generation, and the resulting progeny are referred to as the M2 generation (Fig. 10) [201].

Figure 10: Illustration of the fundamental process involved in a mutation breeding program (Figure adapted from [202])

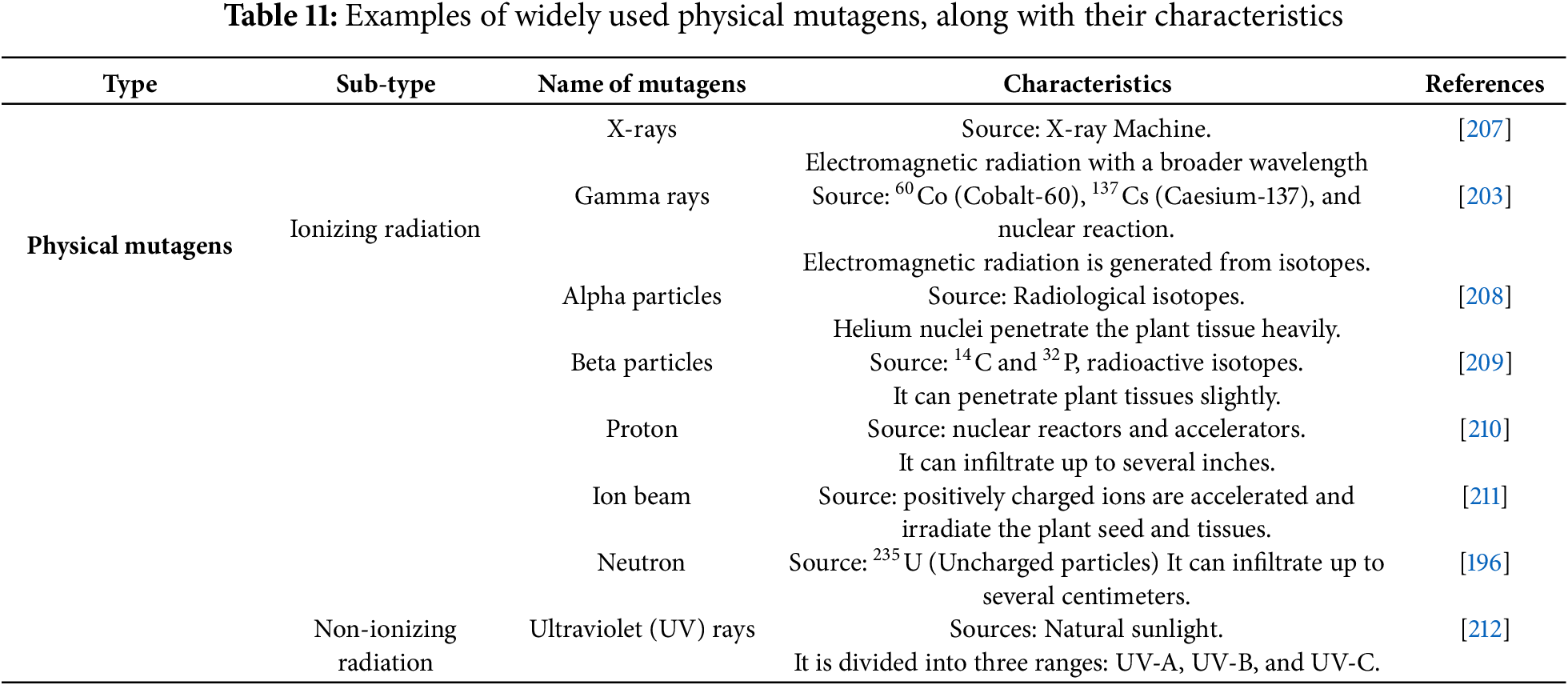

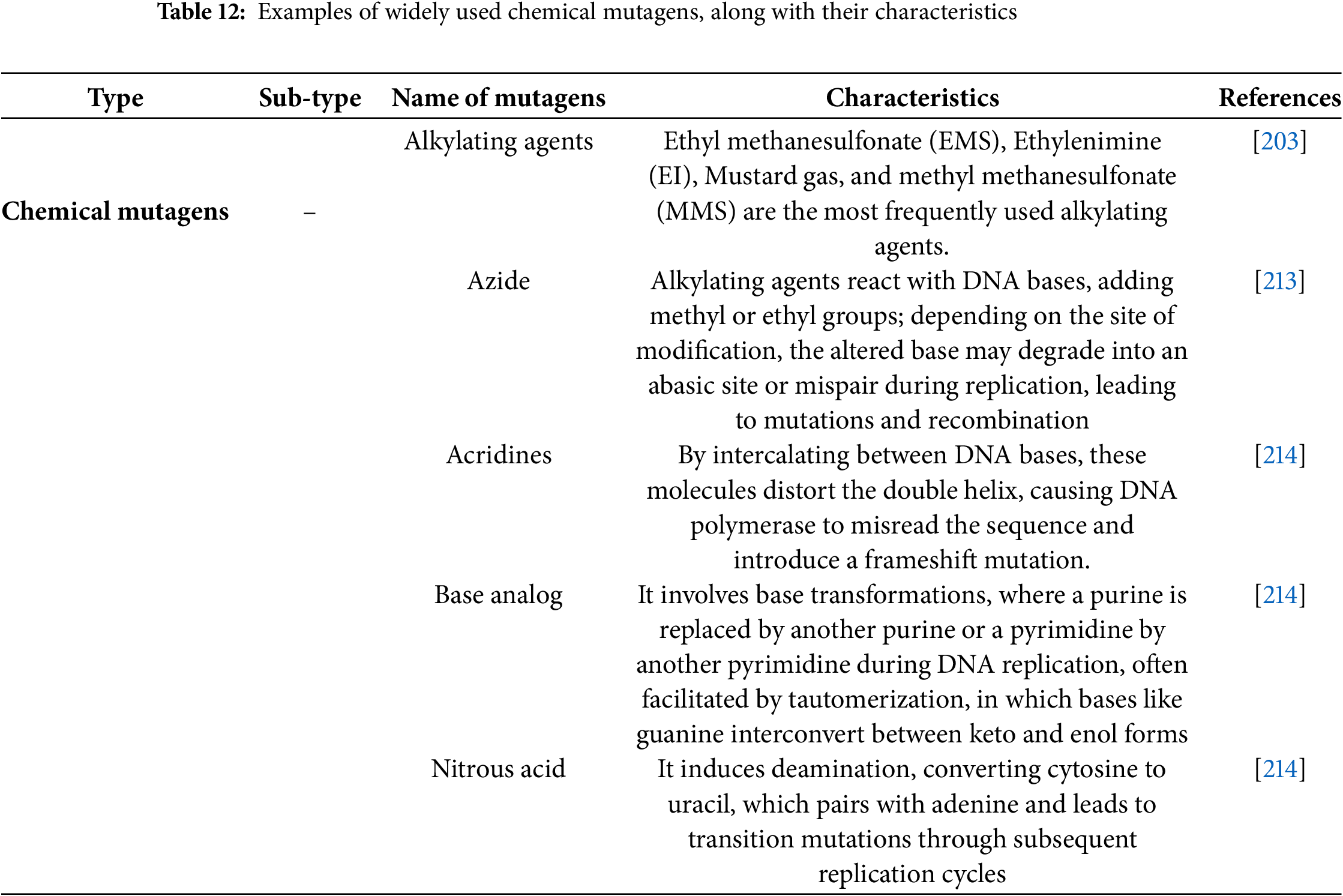

Mutagens are physical (radiation), chemical, and biological agents that induce heritable alterations in DNA, which are irreversible [203]. Mutagens play a significant role in mutation breeding, as specific mutagens have specific mutagenic properties. They are typically classified into two major categories: physical and chemical mutagens [204]. Physical mutagens are further classified into two distinct groups: ionizing radiations (e.g., gamma rays, X-rays, Ion beam, neutrons, alpha and beta particles, Proton) and non-ionizing radiations (e.g., UV rays) [205]. More than a hundred chemical mutagens, classified into several groups, have been identified, including alkylating agents, azides, acridine dyes, nitroso compounds, and base analogues [206]. These mutagens significantly accelerate plant breeding programs and are influential in developing climate-resilient crop cultivars. Types of mutagens with their key characteristic are summarized in Tables 11 and 12.

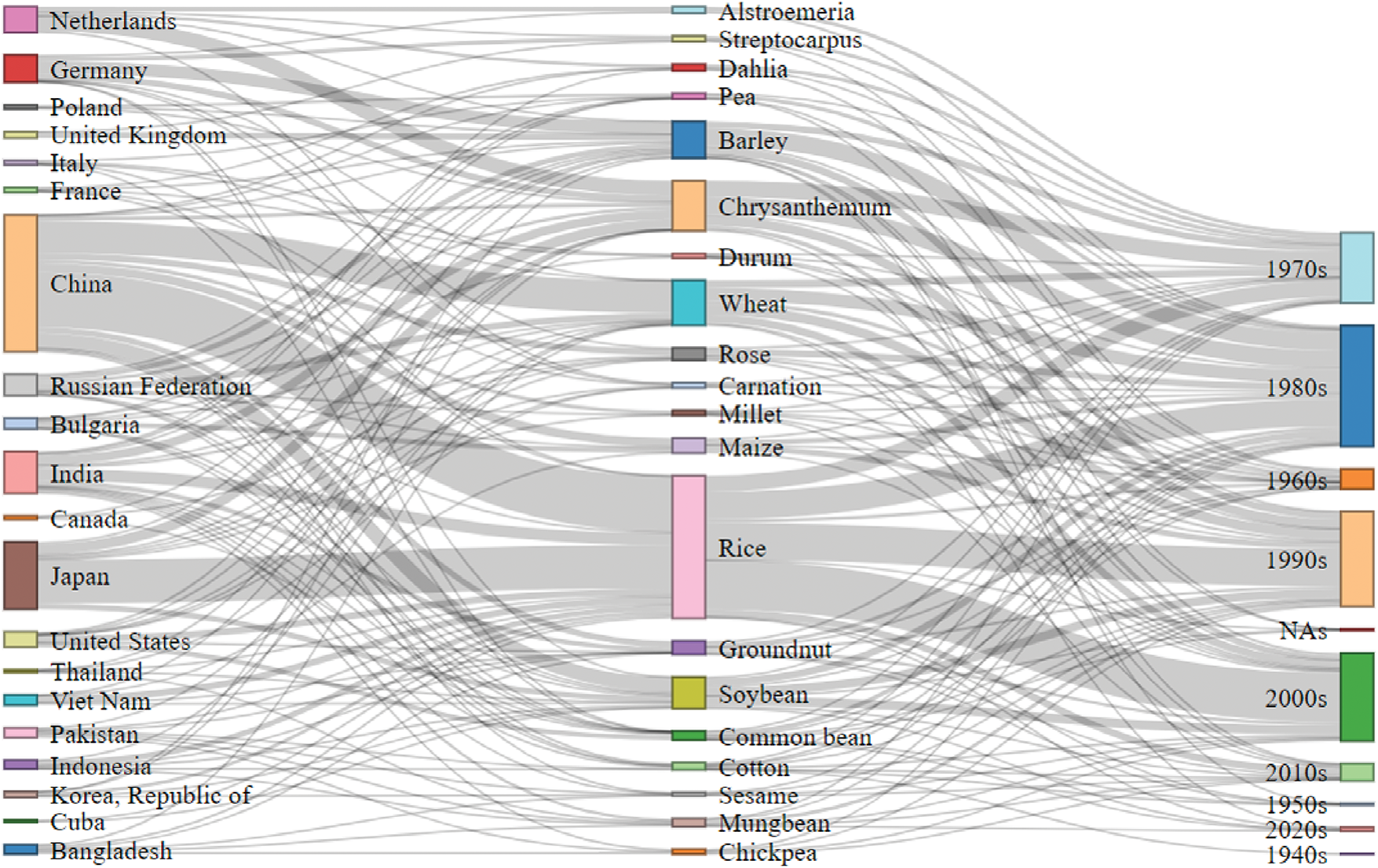

Over the past few decades, mutation breeding has undergone significant advancements. To date, more than 3460 officially released mutant varieties have been developed across 251 plant species in 78 countries (Fig. 11) [215].

Figure 11: A Sankey diagram showing the interrelationship among the common name, the country name, and the registration year of the mutant varieties by using the ‘RStudio’ (https://www.rstudio.com). Data collected from MVD 2025 (https://nucleus.iaea.org/sites/mvd, accessed on 30 April 2025) (Supplementary Material)

9 Integration of Molecular Techniques in Plant Breeding

In the context of the world’s population increase and unprecedented climate change, it seems to be very challenging for agricultural scientists to meet the burgeoning demand for food production. Though the traditional plant breeding approaches have some advantages, it is apparent that this plant breeding method will not be sufficient alone due to having constraints such as limited heritability, low genetic stability, time-consuming, and high costs [216]. Considering this scenario, we need to integrate advanced molecular breeding methods such as genome editing, marker-assisted selection (MAS), high-throughput phenotyping (HTP), etc., to speed up the breeding cycle as well as to ensure precise selection of breeding materials [217]. For example, through marker-assisted transfer of QTL, Saltol from FL478 (a line of salt-tolerant), Pusa Basmati 1 (PB1) showed higher tolerance to salt stress at the seedling stage [77]. The efficiency of varietal development could be significantly improved through the integration of MAS in traditional plant breeding [218]. Genome sequencing technologies can identify the variation in the aim crop, detect desired agronomic traits, and provide the site of gene editing, which consequently reduces the time & cost compared to traditional breeding. Rapid advancements in HTP technologies have shaped the ability to identify stress-tolerant genotypes from the large population of segregants, which assists in innovating the climate-resilient crop varieties [219]. Genome editing technologies like CRISPR-Cas9 are the easiest method to modify the gene sequences to develop abiotic and biotic stress-tolerant cultivars, as well as improve quality traits of crops such as yield, nutritional quality, etc. [220]. Numerous advantages offered by transgenic plants greatly increase crop resilience and agricultural productivity. These plants can be modified to show enhanced resistance to pests, diseases, and herbicides by incorporating particular genes from other organisms. This lessens the need for chemical inputs and encourages eco-friendly agricultural methods. RNA interference (RNAi) is pivotal in silencing specific gene expression and enhancing the desired traits to develop stress-tolerant crop cultivars. Mutagens are highly effective for producing genetic variability and identifying key regulatory sequences associated with economically important traits for crop improvement. Overall, incorporating molecular techniques in plant breeding gives a significant boost in terms of time- and cost-saving, precision, and efficiency.

10 Future Prospects and Conclusion

Although molecular breeding has several advantages over traditional breeding techniques, the future of crop improvement depends on integrating traditional knowledge with modern, cutting-edge technologies. With advancements in molecular methods, we can now achieve food security and meet global food demand more effectively. These technologies make it possible to develop high-yielding crop varieties in a much shorter time.

CRISPR-Cas-mediated genome editing, for example, allows the development of disease-resistant crops without introducing foreign genes. This technique is highly precise, efficient, and capable of eliminating genetic disorders while improving productivity. Future innovations like base editing and prime editing will further enhance the potential of CRISPR technology. Genetic engineering also plays a key role by enabling the direct insertion of traits such as pest resistance and improved crop quality. Similarly, advancements in Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) have made it possible to accelerate breeding through informed parental selection and optimized cross designs. RNA interference (RNAi) is another powerful technique. It is a post-transcriptional gene-silencing method used to achieve pest and disease resistance, as well as trait modification. RNAi is fast, trait-specific, and effective in suppressing harmful or undesirable genes.

High-throughput phenotyping (HTP) supports large-scale screening and helps breeders make better decisions by providing detailed data on plant characteristics. As genomics and bioinformatics continue to advance, Marker-Assisted Selection (MAS) is expected to become even more powerful. The integration of high-throughput genotyping, machine learning, and pan-genome data will allow precise identification of markers linked to complex traits like drought tolerance and disease resistance. Furthermore, speed breeding is also used in crop development as it drastically shortens the time required to produce new varieties. With future improvements in automated phenotyping, controlled environment systems, and AI-driven growth optimization, speed breeding will become even more efficient. When combined with molecular tools such as CRISPR, MAS, and WGS, it will enable the rapid development of crops with higher yields, improved climate resilience, and enhanced nutritional value.

To let this integration model shine, necessary policies should be adopted in the national and international context, technologies should be readily accessible, training must be provided to the relevant stakeholders, and more funding should be allocated to lead such high-value breeding programs.

All things considered, a well-balanced integration of traditional breeding knowledge with modern molecular tools offers greater efficiency, precision, and speed, which consequently will pave the way for a sustainable, more resilient, and food-secure future.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Md. Abdur Rahim; validation, Md. Nahid Hasan and Sk Shoaibur Rahaman; data curation, Md. Nahid Hasan and Sk Shoaibur Rahaman; writing—original draft preparation, Md. Nahid Hasan, Sk Shoaibur Rahaman and Tasmina Islam Simi; writing—review and editing, Md. Abdur Rahim; visualization, Md. Nahid Hasan, Sk Shoaibur Rahaman and Tasmina Islam Simi. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.067633/s1.

References

1. Tkemaladze J. Concept to the food security. Longev Horiz. 2025;1(1):1–13. doi:10.5281/zenodo.14642407; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ullah I, Kamel EAR, Shah ST, Basit A, Mohamed HI, Sajid M. Application of RNAi technology: a novel approach to navigate abiotic stresses. Mol Biol Rep. 2022;49(11):10975–93. doi:10.1007/s11033-022-07871-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Beniwal J, Dhundwal A, Goyal A, Kumari A, Behl RK, Munjal R. Accelerating crop breeding in the 21st century: a comprehensive review of next generation phenotyping techniques and strategies. Ekin J Crop Breed Genet. 2023;9(2):160–71. [Google Scholar]

4. Rosenzweig C, Elliott J, Deryng D, Ruane AC, Müller C, Arneth A, et al. Assessing agricultural risks of climate change in the 21st century in a global gridded crop model intercomparison. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(9):3268–73. doi:10.1073/pnas.1222463110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. von Braun J, Rosegrant M, Pandya-Lorch R, Cohen M, Cline S, Brown M, et al. New risks and opportunities for food security. Washington, DC, USA: International Food Policy Research Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

6. Hallauer AR. Evolution of plant breeding. Crop Breed Appl Biotechnol. 2011;11(3):197–206. doi:10.1590/s1984-70332011000300001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Ahmar S, Gill RA, Jung KH, Faheem A, Qasim MU, Mubeen M, et al. Conventional and molecular techniques from simple breeding to speed breeding in crop plants: recent advances and future outlook. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(7):2590. doi:10.3390/ijms21072590. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Xiong W, Reynolds M, Xu Y. Climate change challenges plant breeding. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2022;70:102308. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2022.102308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Khan MA, Iqbal M, Jameel M, Nazeer W, Shakir S, Aslam MT, et al. Potentials of molecular based breeding to enhance drought tolerance in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Afr J Biotechnol. 2014;10:11340–4. [Google Scholar]

10. Lamichhane S, Thapa S. Advances from conventional to modern plant breeding methodologies. Plant Breed Biotech. 2022;10(1):1–14. doi:10.9787/pbb.2022.10.1.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yang W, Feng H, Zhang X, Zhang J, Doonan JH, Batchelor WD, et al. Crop phenomics and high-throughput phenotyping: past decades, current challenges, and future perspectives. Mol Plant. 2020;13(2):187–214. doi:10.1016/j.molp.2020.01.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Mir RR, Reynolds M, Pinto F, Khan MA, Bhat MA. High-throughput phenotyping for crop improvement in the genomics era. Plant Sci. 2019;282(7):60–72. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.01.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Sheikh M, Iqra F, Ambreen H, Pravin KA, Ikra M, Chung YS. Integrating artificial intelligence and high-throughput phenotyping for crop improvement. J Integr Agric. 2024;23(6):1787–802. doi:10.1016/j.jia.2023.10.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Hamilton JP, Buell CR. Advances in plant genome sequencing. Plant J. 2012;70(1):177–90. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.04894.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Grada A, Weinbrecht K. Next-generation sequencing: methodology and application. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(8):e11–4. doi:10.1038/jid.2013.248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Hasan N, Choudhary S, Naaz N, Sharma N, Laskar RA. Recent advancements in molecular marker-assisted selection and applications in plant breeding programmes. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2021;19(1):128. doi:10.1186/s43141-021-00231-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Kumar R, Das SP, Choudhury BU, Kumar A, Prakash NR, Verma R, et al. Advances in genomic tools for plant breeding: harnessing DNA molecular markers, genomic selection, and genome editing. Biol Res. 2024;57(1):80. doi:10.1186/s40659-024-00562-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Thomson MJ. High-throughput SNP genotyping to accelerate crop improvement. Plant Breed Biotech. 2014;2(3):195–212. doi:10.9787/pbb.2014.2.3.195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ribaut JM, Hoisington D. Marker-assisted selection: new tools and strategies. Trends Plant Sci. 1998;3(6):236–9. doi:10.1016/S1360-1385(98)01240-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Asíns MJ. Present and future of quantitative trait locus analysis in plant breeding. Plant Breed. 2002;121(4):281–91. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0523.2002.730285.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Wada N, Ueta R, Osakabe Y, Osakabe K. Precision genome editing in plants: state-of-the-art in CRISPR/Cas9-based genome engineering. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20(1):234. doi:10.1186/s12870-020-02385-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Erdoğan İ, Cevher-Keskin B, Bilir Ö, Hong Y, Tör M. Recent developments in CRISPR/Cas9 genome-editing technology related to plant disease resistance and abiotic stress tolerance. Biology. 2023;12(7):1037. doi:10.3390/biology12071037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Jagtap UB, Gurav RG, Bapat VA. Role of RNA interference in plant improvement. Naturwissenschaften. 2011;98(6):473–92. doi:10.1007/s00114-011-0798-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Ahmad P, Ashraf M, Younis M, Hu X, Kumar A, Akram NA, et al. Role of transgenic plants in agriculture and biopharming. Biotechnol Adv. 2012;30(3):524–40. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.09.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Rasheed A, Gill RA, Hassan MU, Mahmood A, Qari S, Zaman QU, et al. A critical review: recent advancements in the use of CRISPR/Cas9 technology to enhance crops and alleviate global food crises. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2021;43(3):1950–76. doi:10.3390/cimb43030135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Liu Q, Yang F, Zhang J, Liu H, Rahman S, Islam S, et al. Application of CRISPR/Cas9 in crop quality improvement. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(8):4206. doi:10.3390/ijms22084206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337(6096):816–21. doi:10.1126/science.1225829. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. McCarty NS, Graham AE, Studená L, Ledesma-Amaro R. Multiplexed CRISPR technologies for gene editing and transcriptional regulation. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1281. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-15053-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Modrzejewski D, Hartung F, Sprink T, Krause D, Kohl C, Wilhelm R. What is the available evidence for the range of applications of genome-editing as a new tool for plant trait modification and the potential occurrence of associated off-target effects: a systematic map. Environ Evid. 2019;8(1):27. doi:10.1186/s13750-019-0171-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Hinz JM, Laughery MF, Wyrick JJ. Nucleosomes inhibit Cas9 endonuclease activity in vitro. Biochemistry. 2015;54(48):7063–6. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.5b01108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Liu G, Yin K, Zhang Q, Gao C, Qiu JL. Modulating chromatin accessibility by transactivation and targeting proximal dsgRNAs enhances Cas9 editing efficiency in vivo. Genome Biol. 2019;20(1):145. doi:10.1186/s13059-019-1762-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Modrzejewski D, Hartung F, Lehnert H, Sprink T, Kohl C, Keilwagen J, et al. Which factors affect the occurrence of off-target effects caused by the use of CRISPR/Cas:a systematic review in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:574959. doi:10.3389/fpls.2020.574959. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Liang Z, Chen K, Li T, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Zhao Q, et al. Efficient DNA-free genome editing of bread wheat using CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):14261. doi:10.1038/ncomms14261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Wang Y, Cheng X, Shan Q, Zhang Y, Liu J, Gao C, et al. Simultaneous editing of three homoeoalleles in hexaploid bread wheat confers heritable resistance to powdery mildew. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(9):947–51. doi:10.1038/nbt.2969. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Wang S, Yang Y, Guo M, Zhong C, Yan C, Sun S. Targeted mutagenesis of amino acid transporter genes for rice quality improvement using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Crop J. 2020;8(3):457–64. doi:10.1016/j.cj.2020.02.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Santosh Kumar VV, Verma RK, Yadav SK, Yadav P, Watts A, Rao MV, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 mediated genome editing of drought and salt tolerance (OsDST) gene in indica mega rice cultivar MTU1010. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2020;26(6):1099–110. doi:10.1007/s12298-020-00819-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Gupta A, Liu B, Raza S, Chen QJ, Yang B. Modularly assembled multiplex prime editors for simultaneous editing of agronomically important genes in rice. Plant Commun. 2024;5(2):100741. doi:10.1016/j.xplc.2023.100741. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Xia JQ, Liang QY, He DY, Zhang ZY, Wu J, Zhang J, et al. Knockout of OsSPL10 confers enhanced glufosinate resistance in rice. Plant Commun. 2024;5(2):100731. doi:10.1016/j.xplc.2023.100731. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Ma LY, Zhang AP, Liu J, Zhang N, Chen M, Yang H. Minimized atrazine risks to crop security and its residue in the environment by a rice methyltransferase as a regulation factor. J Agric Food Chem. 2022;70(1):87–98. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.1c04172. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Zhou Y, Shi L, Li X, Wei S, Ye X, Gao Y, et al. Genetic engineering of RuBisCO by multiplex CRISPR editing small subunits in rice. Plant Biotechnol J. 2025;23(3):731–49. doi:10.1111/pbi.14535. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Dong OX, Yu S, Jain R, Zhang N, Duong PQ, Butler C, et al. Marker-free carotenoid-enriched rice generated through targeted gene insertion using CRISPR-Cas9. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1178. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-14981-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Akama K, Akter N, Endo H, Kanesaki M, Endo M, Toki S. An in vivo targeted deletion of the calmodulin-binding domain from rice glutamate decarboxylase 3 (OsGAD3) increases γ-aminobutyric acid content in grains. Rice. 2020;13(1):20. doi:10.1186/s12284-020-00380-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Liu X, Ji P, Liao J, Duan X, Luo Z, Yu X, et al. CRISPR/Cas knockout of the NADPH oxidase gene OsRbohB reduces ROS overaccumulation and enhances heat stress tolerance in rice. Plant Biotechnol J. 2025;23(2):336–51. doi:10.1111/pbi.14500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Ben Shlush I, Samach A, Melamed-Bessudo C, Ben-Tov D, Dahan-Meir T, Filler-Hayut S, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 induced somatic recombination at the CRTISO locus in tomato. Genes. 2020;12(1):59. doi:10.3390/genes12010059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Li J, Jiao G, Sun Y, Chen J, Zhong Y, Yan L, et al. Modification of starch composition, structure and properties through editing of TaSBEIIa in both winter and spring wheat varieties by CRISPR/Cas9. Plant Biotechnol J. 2021;19(5):937–51. doi:10.1111/pbi.13519. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Gao H, Gadlage MJ, Lafitte HR, Lenderts B, Yang M, Schroder M, et al. Superior field performance of waxy corn engineered using CRISPR-Cas9. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38(5):579–81. doi:10.1038/s41587-020-0444-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Hoffie RE, Perovic D, Habekuß A, Ordon F, Kumlehn J. Novel resistance to the Bymovirus BaMMV established by targeted mutagenesis of the PDIL5-1 susceptibility gene in barley. Plant Biotechnol J. 2023;21(2):331–41. doi:10.1111/pbi.13948. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Karlsson M, Kieu NP, Lenman M, Marttila S, Resjö S, Zahid MA, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing of potato St DMR6-1 results in plants less affected by different stress conditions. Hortic Res. 2024;11(7):uhae130. doi:10.1093/hr/uhae130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Pramanik D, Shelake RM, Park J, Kim MJ, Hwang I, Park Y, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated generation of pathogen-resistant tomato against Tomato yellow leaf curl virus and powdery mildew. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(4):1878. doi:10.3390/ijms22041878. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Hong Y, Meng J, He X, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Zhang C, et al. Editing miR482b and miR482c simultaneously by CRISPR/Cas9 enhanced tomato resistance to Phytophthora infestans. Phytopathology. 2021;111(6):1008–16. doi:10.1094/PHYTO-08-20-0360-R. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Silva CJ, van den Abeele C, Ortega-Salazar I, Papin V, Adaskaveg JA, Wang D, et al. Host susceptibility factors render ripe tomato fruit vulnerable to fungal disease despite active immune responses. J Exp Bot. 2021;72(7):2696–709. doi:10.1093/jxb/eraa601. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Yuste-Lisbona FJ, Fernández-Lozano A, Pineda B, Bretones S, Ortíz-Atienza A, García-Sogo B, et al. ENO regulates tomato fruit size through the floral meristem development network. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(14):8187–95. doi:10.1073/pnas.1913688117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Nagy ED, Stevens JL, Yu N, Hubmeier CS, LaFaver N, Gillespie M, et al. Novel disease resistance gene paralogs created by CRISPR/Cas9 in soy. Plant Cell Rep. 2021;40(6):1047–58. doi:10.1007/s00299-021-02678-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Lee S, Park SH, Jeong YJ, Kim S, Kim BR, Ha BK, et al. Optimization of CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein delivery into cabbage protoplasts for efficient DNA-free gene editing. Plant Biotechnol Rep. 2024;18(3):415–24. doi:10.1007/s11816-024-00901-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Wang F, Xu Y, Li W, Chen Z, Wang J, Fan F, et al. Creating a novel herbicide-tolerance OsALS allele using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing. Crop J. 2021;9(2):305–12. doi:10.1016/j.cj.2020.06.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Badhan S, Ball AS, Mantri N. First report of CRISPR/Cas9 mediated DNA-free editing of 4CL and RVE7 genes in chickpea protoplasts. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(1):396. doi:10.3390/ijms22010396. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Khan S, Mahmood MS, Rahman SU, Rizvi F, Ahmad A. Evaluation of the CRISPR/Cas9 system for the development of resistance against Cotton leaf curl virus in model plants. Plant Prot Sci. 2020;56(3):154–62. doi:10.17221/105/2019-pps. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Li P, Li X, Jiang M. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis of WRKY3 and WRKY4 function decreases salt and Me-JA stress tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Biol Rep. 2021;48(8):5821–32. doi:10.1007/s11033-021-06541-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Li B, Liang S, Alariqi M, Wang F, Wang G, Wang Q, et al. The application of temperature sensitivity CRISPR/LbCpf1 (LbCas12a) mediated genome editing in allotetraploid cotton (G. hirsutum) and creation of nontransgenic, gossypol-free cotton. Plant Biotechnol J. 2021;19(2):221–3. doi:10.1111/pbi.13470. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Baeg GJ, Kim SH, Choi DM, Tripathi S, Han YJ, Kim JI. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutation of 5-oxoprolinase gene confers resistance to sulfonamide compounds in Arabidopsis. Plant Biotechnol Rep. 2021;15(6):753–64. doi:10.1007/s11816-021-00718-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Roca Paixão JF, Gillet FX, Ribeiro TP, Bournaud C, Lourenço-Tessutti IT, Noriega DD, et al. Improved drought stress tolerance in Arabidopsis by CRISPR/dCas9 fusion with a Histone AcetylTransferase. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):8080. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-44571-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Ren R, Zheng Q, Ni F, Jin Q, Wan X, Wei J. Breeding for PVY resistance in tobacco LJ911 using CRISPR/Cas9 technology. Crop Breed Appl Biotechnol. 2021;21(1):e31682116. doi:10.1590/1984-70332021v21n1a6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Hu C, Sheng O, Deng G, He W, Dong T, Yang Q, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing of MaACO1 (aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase 1) promotes the shelf life of banana fruit. Plant Biotechnol J. 2021;19(4):654–6. doi:10.1111/pbi.13534. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Hasley J, Dinulong RJ, Adhikari A, Christopher D, Tian M. Genome editing of papaya using both Cas9 and Cas12a. bioRxiv. Forthcoming. 2025. doi:10.1101/2025.05.22.655363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Kumawat G, Kanta Kumawat C, Chandra K, Pandey S, Chand S, Nandan Mishra U, et al. Insights into marker assisted selection and its applications in plant breeding. In: Abdurakhmonov IY, editor. Plant breeding—current and future views. London, UK: IntechOpen; 2021. doi:10.5772/intechopen.95004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Witcombe JR, Virk DS. Number of crosses and population size for participatory and classical plant breeding. Euphytica. 2001;122(3):451–62. doi:10.1023/A:1017524122821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Collard BCY, MacKill DJ. Marker-assisted selection: an approach for precision plant breeding in the twenty-first century. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363(1491):557–72. doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.2170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Collard BCY, Jahufer MZZ, Brouwer JB, Pang ECK. An introduction to markers, quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping and marker-assisted selection for crop improvement: the basic concepts. Euphytica. 2005;142(1):169–96. doi:10.1007/s10681-005-1681-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Vagndorf N, Kristensen PS, Andersen JR, Jahoor A, Orabi J. Marker-assisted breeding in wheat. In: Çiftçi YÖ, editor. Next generation plant breeding. London, UK: IntechOpen; 2018. doi:10.5772/intechopen.74724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Mondini L, Noorani A, Pagnotta MA. Assessing plant genetic diversity by molecular tools. Diversity. 2009;1(1):19–35. doi:10.3390/d1010019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Nadeem MA, Nawaz MA, Shahid MQ, Doğan Y, Comertpay G, Yıldız M, et al. DNA molecular markers in plant breeding: current status and recent advancements in genomic selection and genome editing. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2018;32(2):261–85. doi:10.1080/13102818.2017.1400401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Kalia RK, Rai MK, Kalia S, Singh R, Dhawan AK. Microsatellite markers: an overview of the recent progress in plants. Euphytica. 2011;177(3):309–34. doi:10.1007/s10681-010-0286-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Matsuda K. Chapter two—PCR-based detection methods for single-nucleotide polymorphism or mutation: real-time PCR and its substantial contribution toward technological refinement. In: Makowski GS, editor. Advances in clinical chemistry. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2017. p. 45–72. doi:10.1016/bs.acc.2016.11.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Hong YH, Xiao N, Zhang C, Su Y, Chen JM. Principle of diversity arrays technology (DArT) and its applications in genetic research of plants. Hereditas. 2009;31(4):359–64. (In Chinese). doi:10.3724/sp.j.1005.2009.00359. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Das G, Rao GJN. Molecular marker assisted gene stacking for biotic and abiotic stress resistance genes in an elite rice cultivar. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:698. doi:10.3389/fpls.2015.00698. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Hospital F. Challenges for effective marker-assisted selection in plants. Genetica. 2009;136(2):303–10. doi:10.1007/s10709-008-9307-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Singh VK, Singh BD, Kumar A, Maurya S, Krishnan SG, Vinod KK, et al. Marker-assisted introgression of Saltol QTL enhances seedling stage salt tolerance in the rice variety “Pusa Basmati 1”. Int J Genomics. 2018;2018:8319879. doi:10.1155/2018/8319879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Basavaraj SH, Singh VK, Singh A, Singh A, Singh A, Anand D, et al. Marker-assisted improvement of bacterial blight resistance in parental lines of Pusa RH10, a superfine grain aromatic rice hybrid. Mol Breeding. 2010;26(2):293–305. doi:10.1007/s11032-010-9407-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Boopathi NM. Genetic mapping and marker assisted selection: basics, practice and benefits. 2nd ed. Singapore: Springer; 2020. 504 p. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-2949-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Tester M, Langridge P. Breeding technologies to increase crop production in a changing world. Science. 2010;327(5967):818–22. doi:10.1126/science.1183700. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Wu JW, Hu CY, Shahid MQ, Guo HB, Zeng YX, Liu XD, et al. Analysis on genetic diversification and heterosis in autotetraploid rice. SpringerPlus. 2013;2(1):439. doi:10.1186/2193-1801-2-439. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. He J, Zhao X, Laroche A, Lu ZX, Liu H, Li Z. Genotyping-by-sequencing (GBSan ultimate marker-assisted selection (MAS) tool to accelerate plant breeding. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:484. doi:10.3389/fpls.2014.00484. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Brumlop S, Reichenbecher W, Tappeser B, Finckh MR. What is the smartest way to breed plants and increase agrobiodiversity? Euphytica. 2013;194(1):53–66. doi:10.1007/s10681-013-0960-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Gupta PK, Kumar J, Mir RR, Kumar A. Marker-assisted selection as a component of conventional plant breeding. In: Janick J, editor. Plant breeding reviews. 1st ed. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2010. p. 145–217. doi:10.1002/9780470535486.ch4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Francia E, Tacconi G, Crosatti C, Barabaschi D, Bulgarelli D, Dall’Aglio E, et al. Marker assisted selection in crop plants. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 2005;82(3):317–42. doi:10.1007/s11240-005-2387-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Sharma TR, Devanna BN, Kiran K, Singh PK, Arora K, Jain P, et al. Status and prospects of next generation sequencing technologies in crop plants. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2018;27:1–36. doi:10.21775/cimb.027.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Berkman PJ, Lai K, Lorenc MT, Edwards D. Next-generation sequencing applications for wheat crop improvement. Am J Bot. 2012;99(2):365–71. doi:10.3732/ajb.1100309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Soundararajan P, Won SY, Kim JS. Insight on Rosaceae family with genome sequencing and functional genomics perspective. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019(3):7519687. doi:10.1155/2019/7519687. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Varshney RK, Pandey MK, Bohra A, Singh VK, Thudi M, Saxena RK. Toward the sequence-based breeding in legumes in the post-genome sequencing era. Theor Appl Genet. 2019;132(3):797–816. doi:10.1007/s00122-018-3252-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Hudson ME. Sequencing breakthroughs for genomic ecology and evolutionary biology. Mol Ecol Resour. 2008;8(1):3–17. doi:10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.02019.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Roy A, Dutta S, Das S, Choudhury MR. Next-generation sequencing in the development of climate-resilient and stress-responsive crops—a review. Open Biotechnol J. 2024;18(1):e18740707301657. doi:10.2174/0118740707301657240517063244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

92. Abdul Aziz M, Masmoudi K. Molecular breakthroughs in modern plant breeding techniques. Hortic Plant J. 2025;11(1):15–41. doi:10.1016/j.hpj.2024.01.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Huq MA, Akter S, Jung YJ, Nou IS, Cho YG, Kang KK. Genome sequencing, a milestone for genomic research and plant breeding. Plant Breed Biotech. 2016;4(1):29–39. doi:10.9787/pbb.2016.4.1.29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Chhapekar SS, Gaur R, Kumar A, Ramchiary N. Reaping the benefits of next-generation sequencing technologies for crop improvement—Solanaceae. In: Kulski JK, editor. Next generation sequencing—advances, applications and challenges. London, UK: InTechOpen; 2016. doi:10.5772/61656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Singh AK, Pal P, Sahoo UK, Sharma L, Pandey B, Prakash A, et al. Enhancing crop resilience: the role of plant genetics, transcription factors, and next-generation sequencing in addressing salt stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(23):12537. doi:10.3390/ijms252312537. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Varshney RK, Terauchi R, McCouch SR. Harvesting the promising fruits of genomics: applying genome sequencing technologies to crop breeding. PLoS Biol. 2014;12(6):e1001883. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001883. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Glenn TC. Field guide to next-generation DNA sequencers. Mol Ecol Resour. 2011;11(5):759–69. doi:10.1111/j.1755-0998.2011.03024.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Qin D. Next-generation sequencing and its clinical application. Cancer Biol Med. 2019;16(1):4–10. doi:10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2018.0055. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Sasaki T. The map-based sequence of the rice genome. Nature. 2005;436(7052):793–800. doi:10.1038/nature03895. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Zimin AV, Puiu D, Hall R, Kingan S, Clavijo BJ, Salzberg SL. The first near-complete assembly of the hexaploid bread wheat genome, Triticum aestivum. Gigascience. 2017;6(11):1–7. doi:10.1093/gigascience/gix097. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Realini MF, Poggio L, Cámara-Hernández J, González GE. Intra-specific variation in genome size in maize: cytological and phenotypic correlates. AoB Plants. 2015;8:plv138. doi:10.1093/aobpla/plv138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Wicker T, Taudien S, Houben A, Keller B, Graner A, Platzer M, et al. A whole-genome snapshot of 454 sequences exposes the composition of the barley genome and provides evidence for parallel evolution of genome size in wheat and barley. Plant J. 2009;59(5):712–22. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03911.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Xu X, Pan S, Cheng S, Zhang B, Mu D, Ni P, et al. Genome sequence and analysis of the tuber crop potato. Nature. 2011;475(7355):189–95. doi:10.1038/nature10158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. The Tomato Genome Consortium. The tomato genome sequence provides insights into fleshy fruit evolution. Nature. 2012;485(7400):635–41. doi:10.1038/nature11119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Sierro N, Battey JND, Ouadi S, Bakaher N, Bovet L, Willig A, et al. The tobacco genome sequence and its comparison with those of tomato and potato. Nat Commun. 2014;5(1):3833. doi:10.1038/ncomms4833. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Zhang J, Nagai C, Yu Q, Pan YB, Ayala-Silva T, Schnell RJ, et al. Genome size variation in three Saccharum species. Euphytica. 2012;185(3):511–9. doi:10.1007/s10681-012-0664-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

107. Cannon SB, Shoemaker RC. Evolutionary and comparative analyses of the soybean genome. Breed Sci. 2012;61(5):437–44. doi:10.1270/jsbbs.61.437. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Takvorian N, Zangui H, Naino Jika AK, Alouane A, Siljak-Yakovlev S. Genome size variation in Sesamum indicum L. germplasm from niger. Genes. 2024;15(6):711. doi:10.3390/genes15060711. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Kang YJ, Kim SK, Kim MY, Lestari P, Kim KH, Ha BK, et al. Genome sequence of mungbean and insights into evolution within Vigna species. Nat Commun. 2014;5(1):5443. doi:10.1038/ncomms6443. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Wei Q, Wang J, Wang W, Hu T, Hu H, Bao C. A high-quality chromosome-level genome assembly reveals genetics for important traits in eggplant. Hortic Res. 2020;7(1):153. doi:10.1038/s41438-020-00391-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

111. Santos Araújo F, Carvalho CR, Clarindo WR. Genome size, base composition and karyotype of Carica papaya L. The Nucleus. 2010;53(1):25–31. doi:10.1007/s13237-010-0007-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

112. Paterson AH, Bowers JE, Bruggmann R, Dubchak I, Grimwood J, Gundlach H, et al. The Sorghum bicolor genome and the diversification of grasses. Nature. 2009;457(7229):551–6. doi:10.1038/nature07723. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

113. Lysak MA, Cheung K, Kitschke M, Bures P. Ancestral chromosomal blocks are triplicated in Brassiceae species with varying chromosome number and genome size. Plant Physiol. 2007;145(2):402–10. doi:10.1104/pp.107.104380. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

114. Zhang K, Yu H, Zhang L, Cao Y, Li X, Mei Y, et al. Transposon proliferation drives genome architecture and regulatory evolution in wild and domesticated peppers. Nat Plants. 2025;11(2):359–75. doi:10.1038/s41477-025-01905-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

115. Huang G, Huang JQ, Chen XY, Zhu YX. Recent advances and future perspectives in cotton research. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2021;72(1):437–62. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-080720-113241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

116. Wei C, Yang H, Wang S, Zhao J, Liu C, Gao L, et al. Draft genome sequence of Camellia sinensis var. sinensis provides insights into the evolution of the tea genome and tea quality. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(18):E4151–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.1719622115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

117. Zhang L, Ma X, Zhang X, Xu Y, Ibrahim AK, Yao J, et al. Reference genomes of the two cultivated jute species. Plant Biotechnol J. 2021;19(11):2235–48. doi:10.1111/pbi.13652. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

118. Finkers R, van Kaauwen M, Ament K, Burger-Meijer K, Egging R, Huits H, et al. Insights from the first genome assembly of onion (Allium cepa). G3. 2021;11(9):jkab243. doi:10.1093/g3journal/jkab243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

119. Peace CP, Bianco L, Troggio M, van de Weg E, Howard NP, Cornille A, et al. Apple whole genome sequences: recent advances and new prospects. Hortic Res. 2019;6(1):59. doi:10.1038/s41438-019-0141-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

120. Bosher JM, Labouesse M. RNA interference: genetic wand and genetic watchdog. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2(2):E31–6. doi:10.1038/35000102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

121. Cogoni C, Macino G. Post-transcriptional gene silencing across Kingdoms. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10(6):638–43. doi:10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00134-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

122. Saurabh S, Vidyarthi AS, Prasad D. RNA interference: concept to reality in crop improvement. Planta. 2014;239(3):543–64. doi:10.1007/s00425-013-2019-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

123. Oshunsanya SO, Nwosu NJ, Li Y. Abiotic stress in agricultural crops under climatic conditions. In: Jhariya MK, Banerjee A, Meena RS, Yadav DK, editors. Sustainable agriculture, forest and environmental management. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2019. p. 71–100. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-6830-1_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

124. Kopecká R, Kameniarová M, Černý M, Brzobohatý B, Novák J. Abiotic stress in crop production. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(7):6603. doi:10.3390/ijms24076603. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

125. Tester M, Bacic A. Abiotic stress tolerance in grasses. from model plants to crop plants. Plant Physiol. 2005;137(3):791–3. doi:10.1104/pp.104.900138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

126. Tiwari R, Rajam MV. RNA- and miRNA-interference to enhance abiotic stress tolerance in plants. J Plant Biochem Biotechnol. 2022;31(4):689–704. doi:10.1007/s13562-022-00770-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

127. Lin Z, Yi X, Ali MM, Zhang L, Wang S, Tian S, et al. RNAi-mediated suppression of OsBBTI5 promotes salt stress tolerance in rice. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(2):1284. doi:10.3390/ijms25021284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

128. Zuo J, Wei C, Liu X, Jiang L, Gao J. Multifunctional transcription factor YABBY6 regulates morphogenesis, drought and cold stress responses in rice. Rice. 2024;17(1):69. doi:10.1186/s12284-024-00744-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

129. Mao X, Yu H, Xue J, Zhang L, Zhu Q, Lv S, et al. OsRHS negatively regulates rice heat tolerance at the flowering stage by interacting with the HSP protein cHSP70-4. Plant Cell Environ. 2025;48(1):350–64. doi:10.1111/pce.15152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

130. Wei L, Ren X, Qin L, Zhang R, Cui M, Xia G, et al. TaWRKY55-TaPLATZ2 module negatively regulate saline-alkali stress tolerance in wheat. J Integr Plant Biol. 2025;67(1):19–34. doi:10.1111/jipb.13793. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

131. Li Q, Zhao X, Wu J, Shou H, Wang W. The F-box protein TaFBA1 positively regulates drought resistance and yield traits in wheat. Plants. 2024;13(18):2588. doi:10.3390/plants13182588. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

132. Hao XY, Yu TF, Peng CJ, Fu YH, Fang YH, Li Y, et al. Somatic embryogenetic receptor kinase TaSERL2 regulates heat stress tolerance in wheat by influencing TaBZR2 protein stability and transcriptional activity. Plant Biotechnol J. 2025;23(7):2537–53. doi:10.1111/pbi.70045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

133. Pan Y, Han T, Xiang Y, Wang C, Zhang A. The transcription factor ZmNAC84 increases maize salt tolerance by regulating ZmCAT1 expression. Crop J. 2024;12(5):1344–56. doi:10.1016/j.cj.2024.09.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

134. Balassa G, Balassa K, Janda T, Rudnóy S. Expression pattern of RNA interference genes during drought stress and MDMV infection in maize. J Plant Growth Regul. 2022;41(5):2048–58. doi:10.1007/s00344-022-10651-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

135. Li S, Wang Y, Liu Y, Liu C, Xu W, Lu Y, et al. Sucrose synthase gene SUS3 could enhance cold tolerance in tomato. Front Plant Sci. 2024;14:1324401. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1324401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

136. Luo Y, Wang K, Zhu L, Zhang N, Si H. StMAPKK5 positively regulates response to drought and salt stress in potato. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(7):3662. doi:10.3390/ijms25073662. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

137. Ansari MS, Moraiet MA, Ahmad S. Insecticides: impact on the environment and human health. In: Malik A, Grohmann E, Akhtar R, editor. Environmental deterioration and human health. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer Netherlands; 2013. p. 99–123. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7890-0_6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

138. Duan CG, Wang CH, Guo HS. Application of RNA silencing to plant disease resistance. Silence. 2012;3(1):5. doi:10.1186/1758-907X-3-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

139. Younis A, Siddique MI, Kim CK, Lim KB. RNA interference (RNAi) induced gene silencing: a promising approach of hi-tech plant breeding. Int J Biol Sci. 2014;10(10):1150–8. doi:10.7150/ijbs.10452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

140. Chen P, Lan Y, Ding S, Du R, Hu X, Zhang H, et al. RNA interference-based dsRNA application confers prolonged protection against rice blast and viral diseases, offering a scalable solution for enhanced crop disease management. J Integr Plant Biol. 2025;67(6):1633–48. doi:10.1111/jipb.13896. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

141. Tyagi H, Rajasubramaniam S, Rajam MV, Dasgupta I. RNA-interference in rice against Rice tungro bacilliform virus results in its decreased accumulation in inoculated rice plants. Transgenic Res. 2008;17(5):897–904. doi:10.1007/s11248-008-9174-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

142. Cruz LF, Rupp JLS, Trick HN, Fellers JP. Stable resistance to Wheat streak mosaic virus in wheat mediated by RNAi. Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant. 2014;50(6):665–72. doi:10.1007/s11627-014-9634-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

143. Blyuss KB, Fatehi F, Tsygankova VA, Biliavska LO, Iutynska GO, Yemets AI, et al. RNAi-based biocontrol of wheat nematodes using natural poly-component biostimulants. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:483. doi:10.3389/fpls.2019.00483. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

144. Niu X, Kassa A, Hu X, Robeson J, McMahon M, Richtman NM, et al. Control of western corn rootworm (Diabrotica virgifera Virgifera) reproduction through plant-mediated RNA interference. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):12591. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-12638-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

145. Necira K, Contreras L, Kamargiakis E, Kamoun MS, Canto T, Tenllado F. Comparative analysis of RNA interference and pattern-triggered immunity induced by dsRNA reveals different efficiencies in the antiviral response to potato virus X. Mol Plant Pathol. 2024;25(9):e70008. doi:10.1111/mpp.70008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

146. Yoon J, Fang M, Lee D, Park M, Kim KH, Shin C. Double-stranded RNA confers resistance to pepper mottle virus in Nicotiana benthamiana. Appl Biol Chem. 2021;64(1):1. doi:10.1186/s13765-020-00581-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

147. Chang HH, Tzean Y, Yeh HH. Harnessing viral promoters for targeted RNAi: engineering phloem-specific resistance against Tomato yellow leaf curl Thailand virus. In: Marchisio MA, editor. Synthetic promoters. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2024. p. 239–45. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-4063-0_16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

148. Dunoyer P, Himber C, Voinnet O. Induction, suppression and requirement of RNA silencing pathways in virulent Agrobacterium tumefaciens infections. Nat Genet. 2006;38(2):258–63. doi:10.1038/ng1722. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

149. Mao YB, Tao XY, Xue XY, Wang LJ, Chen XY. Cotton plants expressing CYP6AE14 double-stranded RNA show enhanced resistance to bollworms. Transgenic Res. 2011;20(3):665–73. doi:10.1007/s11248-010-9450-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

150. Mamta, Reddy KRK, Rajam MV. Targeting chitinase gene of Helicoverpa armigera by host-induced RNA interference confers insect resistance in tobacco and tomato. Plant Mol Biol. 2016;90(3):281–92. doi:10.1007/s11103-015-0414-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

151. Kamaraju D, Chatterjee M, Papolu PK, Shivakumara TN, Sreevathsa R, Hada A, et al. Host-induced RNA interference targeting the neuromotor gene FMRFamide-like peptide-14 (Mi-flp14) perturbs Meloidogyne incognita parasitic success in eggplant. Plant Cell Rep. 2024;43(7):178. doi:10.1007/s00299-024-03259-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

152. Jhansi Rani S, Usha R. Transgenic plants: types, benefits, public concerns and future. J Pharm Res. 2013;6(8):879–83. doi:10.1016/j.jopr.2013.08.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

153. Venkataraman S, Badar U, Hefferon K. Agricultural innovation and the global politics of food trade. In: Ferranti P, Berry EM, Anderson JR, editors. Encyclopedia of food security and sustainability. Oxford, UK: Elsevier; 2019. p. 114–21. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-100596-5.22067-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

154. Mohan Babu R, Sajeena A, Seetharaman K, Reddy MS. Advances in genetically engineered (transgenic) plants in pest management—an over view. Crop Prot. 2003;22(9):1071–86. doi:10.1016/S0261-2194(03)00142-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

155. Ghimire BK, Yu CY, Kim WR, Moon HS, Lee J, Kim SH, et al. Assessment of benefits and risk of genetically modified plants and products: current controversies and perspective. Sustainability. 2023;15(2):1722. doi:10.3390/su15021722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

156. Šutković J, Hamad N, Glamočlija P. The methods behind transgenic plant production: a review. Period Eng Nat Sci. 2021;9(4):845. doi:10.21533/pen.v9i4.1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

157. Shimizu T, Ogamino T, Hiraguri A, Nakazono-Nagaoka E, Uehara-Ichiki T, Nakajima M, et al. Strong resistance against Rice grassy stunt virus is induced in transgenic rice plants expressing double-stranded RNA of the viral genes for nucleocapsid or movement proteins as targets for RNA interference. Phytopathology. 2013;103(5):513–9. doi:10.1094/PHYTO-07-12-0165-R. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]