Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Phenolic Profiling and Bioactive Potential of Iris bucharica

1 Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, National University of Pharmacy, Valentynivska Str. 4, Kharkiv, 61168, Ukraine

2 Department of Pharmaceutical and Biological Chemistry, Pharmacognosy and Phytotherapy Group, UCL School of Pharmacy, 29-39 Brunswick Square, London, WC1N 1AX, UK

3 Department of Pharmaceutical Biology, Kiel University, Kiel, 24118, Germany

4 State Scientific Research Institute Nature Research Centre, Akademijos Str. 2, Vilnius, 08412, Lithuania

5 Department of Analytical and Toxicological Chemistry, Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, A. Mickevičiaus Str. 9, Kaunas, 44307, Lithuania

6 Graduate Institute of Natural Products, College of Pharmacy, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, 80708, Taiwan

7 Department of Medical Research, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, 80708, Taiwan

8 Drug Development and Value Creation Research Center, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, 80708, Taiwan

9 Research Center for Emerging Viral Infections, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, 33302, Taiwan

10 Graduate Institute of Natural Products, College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, 33302, Taiwan

11 Center for Drug Research and Development, College of Human Ecology, Chang Gung University of Science and Technology, Taoyuan, 33303, Taiwan

12 Graduate Institute of Health Industry Technology, College of Human Ecology, Chang Gung University of Science and Technology, Taoyuan, 33303, Taiwan

13 Department of Anaesthesiology, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taoyuan, 33305, Taiwan

14 Department of Biotechnology, College of Life Sciences, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, 80708, Taiwan

15 Institute of Biomedical Sciences, National Sun Yat‑sen University, Kaohsiung, 804201, Taiwan

* Corresponding Authors: Olha Mykhailenko. Email: ; Michal Korinek. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Secondary Metabolites in Plants and Their Interaction With Ecological Factors)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2026, 95(1), 4 https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2026.074209

Received 05 October 2025; Accepted 31 December 2025; Issue published 30 January 2026

Abstract

The sustainable sourcing of novel bioactive compounds from natural sources is crucial to the success of the pharmaceutical, food, and cosmetics industries. Iris bucharica Foster (syn. Juno bucharica (Foster) Vved.) is a promising source of novel bioactive molecules, particularly phenolic compounds, which are renowned for their antioxidant properties. In this study, we developed a reliable HPLC-UV-DAD method to identify and quantify phenolic compounds in the leaves and bulbs of I. bucharica, establishing the first set of quality control markers for this species. A total of 21 phenolic compounds were identified in the leaves, with flavonoids isoorientin, guaijaverin, hyperoside, and cosmosiin, the isoflavonoid biochanin A, and the simple phenolic ferulic acid being the most prominent. In comparison, 14 compounds were identified in the bulbs, primarily isoflavonoids, including tectoridin and germanaism B, and flavonoid apigenin. The leaves extracts exhibited significant antioxidant activity, whereas the anti-allergic and anti-inflammatory effects were mild. These findings highlight I. bucharica as a sustainable source of bioactive compounds with potential industrial applications. However, further studies are needed to evaluate bioavailability and in vivo efficacy, as well as to optimise extraction methods to realize its industrial potential fully.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FilePlants are an essential source of secondary metabolites, which are renowned for their broad pharmacological activity and relatively low incidence of side effects. Phenolic compounds, in particular, are highly valued for their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and other health-promoting properties [1]. Reliable identification of these compounds is essential for the quality control and the therapeutic application of herbal products.

Iris bucharica Foster (syn. Juno bucharica (Foster) Vved.), a member of the Iridaceae family and the Scorpiris subgenus, is a bulbous species that has not been the subject of extensive phytochemical research. While the pharmacological potential of species from other Iris subgenera (e.g., subg. Iris and subg. Limniris (Tausch) Spach) has been extensively studied [2,3,4], I. bucharica remains largely unstudied.

In its broadest sense, the genus Iris comprises over 300 species, distributed throughout Europe, Asia, North America, and North Africa [5,6]. There are currently two competing approaches to classifying the genus. Some taxonomists accept the broad concept of the genus Iris, dividing it into several subgenera [5,6]. In contrast, others argue that it is necessary to divide the broad genus into a dozen or so narrowly defined genera [5,7]. Traditionally, plants classified as Iris subg. Scorpiris have characteristic bulbs, true bifacial leaves and flowers that grow at the base of well-developed leaves. These plants are sometimes considered to constitute a separate genus, Juno Tratt [7].

Iris bucharica is distributed in Central Asia (Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan). However, its successful cultivation in Eastern Europe highlights the importance of assessing whether ecological relocation influences its secondary metabolite profile. Environmental factors such as light intensity, soil composition, and climatic stressors are known to modulate the accumulation of phenolic compounds in plants [8]. As phenolic secondary metabolites serve as both defense molecules and quality control markers for pharmacological applications [9,10], characterizing them in both native and introduced habitats is crucial. Understanding this contributes to our knowledge of plant adaptation strategies. It provides a basis for the sustainable use of I. bucharica as a source of bioactive compounds in medicine and biotechnology.

Plants of the Iridaceae family contain various bioactive compounds, including phenolic compounds [4,9,11,12]. Previous research on I. bucharica has reported the presence of amino acids in the leaves and bulbs [13], as well as polysaccharides in the bulbs [14]. Nevertheless, there is currently no comprehensive data on its phenolic composition or associated bioactivities.

A few of the bulbous species of the genus Iris have been the focus of more extensive studies. Iris persica L. (subg. Scorpiris), native to Iran, exhibits a highly diverse chemical composition. This includes essential oils (e.g., phenylethanol, furfural) in the leaves and rhizomes [4], phenolic compounds (e.g., isoquercitrin, kaempferol-3-glucoside, and luteolin) in the stems, leaves, and flowers [15], and tectorigenin in the bulbs [16]. Phytochemical studies of the fresh bulbs of Iris tingitana Boiss. & Reut., which is now classified in subg. Xiphium led to the isolation of irisolone methyl ether, 5,4′-dimethoxy-3′-hydroxy-6,7-methylenedioxyisoflavone, and acetovanillone [17], stilbene glucosides (e.g., tingitanol A and tingitanol B), and genistein derivatives [18].

This study addresses the following knowledge gaps: (i) the absence of a detailed phenolic profile of I. bucharica leaves and bulbs, and (ii) the lack of data on its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and other biopharmacological properties. By investigating these aspects, we aim to lay the groundwork for the potential medicinal and biotechnological applications of I. bucharica.

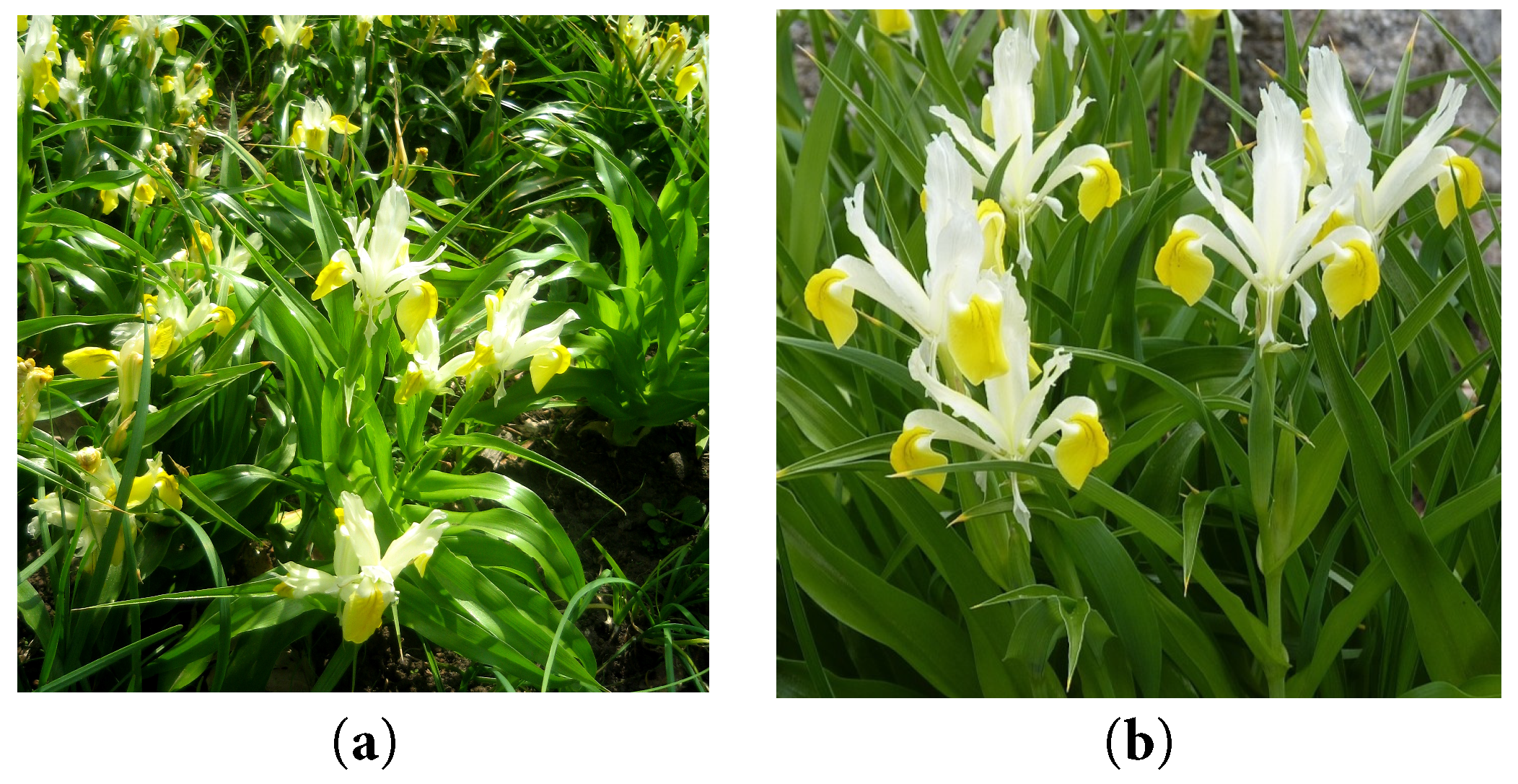

Iris bucharica Foster (Juno bucharica (Foster) Vved.) is a 30–40 cm tall perennial bulbous plant with a yellowish-white bulb about 2 cm in diameter and a papery tunic. It has fine, fleshy roots. The leaves are sword-shaped, 10–20 cm long, and imbricate at the base of the stem. The upper surface of the leaves is glossy, bright green, while the lower surface is greenish-grey or bluish. Flowers are usually 5–7 per stem, 4–5 cm in diameter, and are arranged in the axils of upper leaves. Outer petals are large, reflecting outwards, yellow (varying from pale lemon to golden yellow). Inner petals are smaller, erect, and white (Fig. 1). The plant is native to Central Asia (Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan). In its native range, it grows between pebbles along rivers and on gravelly slopes, usually at an altitude of 1500–1800 m above sea level. Elsewhere, including Ukraine, it is occasionally cultivated as an ornamental plant.

Figure 1: A group of flowering Iris bucharica in cultivation (a) and a close-up view of the flowers (b). Photographs by O. Mykhailenko and Z. Gudžinskas.

For this study, the herbal raw material (HRM) in the form of the leaves and bulbs of Iris bucharica (CWU00562019 and CWU00572019) was selected due to its adaptation to the climatic conditions of Ukraine and popularity among farmers, ensuring a reliable supply of raw materials [19,20]. The plant material was harvested in 2019 from the Botanical Garden of V.M. Karazin of Kharkiv National University, Kharkiv, Ukraine (Fig. 2). The raw materials were dried using both air-shadow and convective methods at a temperature of 55 ± 5°C.

Figure 2: The aerial parts of Iris bucharica cultivated at the Botanical Garden of V.M. Karazin, Kharkiv National University, Ukraine, in autumn 2019 (a) and its cleaned bulbs (b). Photographs by O. Mykhailenko.

2.3 Physicochemical Parameters

Five batches of raw materials were studied using the gravimetric method, as specified in the State Pharmacopoeia of Ukraine [21]. Loss on drying was determined according to the article “Weight loss on drying” (2.2.32). The total ash content was determined according to the article “Total ash” (2.4.16). Ash insoluble in hydrochloric acid was determined according to the article “Ash insoluble in hydrochloric acid” (2.8.1). The determination of extractive compound content in the raw material was carried out according to the article “Determination of dry residue of extracts” (2.8.16). The analysis was performed using an AXIS electronic laboratory balance AN 100 and a 2Sh-01-01 drying cabinet.

The qualitative composition of phytochemicals in plant extracts was determined using previously described methods [22,23]. Phenolic compounds were identified using thin-layer chromatography (TLC) method and reliable samples of flavonoids and hydroxycinnamic acids with the following solvent system: acetic acid R–formic acid anhydrous R–water R–ethyl acetate R (11:11:27:100, R stands for “reagent grade”). For the derivatization of samples was used spraying with a solution of 10 g/L diphenylboroinic acid aminoethyl ester R (Naturstoffreagenz A) in methanol R, after that plates were heated at 100–105°C for 10 min. The spots on the plates were examined in daylight and under UV light at a wavelength of 365 nm. The analytical standards of phenolic compounds for TLC and HPLC analyses were the same.

2.5 Spectrophotometric Determination

The quantitative content of bioactive compounds (total polyphenols, flavonoids, hydroxycinnamic acids, and isoflavonoids) and antioxidant activity in vitro in I. bucharica leaves and bulbs were studied following the requirements of the State Pharmacopoeia of Ukraine article 2.0, “Absorption spectrophotometry in the ultraviolet and visible regions” (2.2.25) using a Halo DB-20 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Techcomp Europe, UK). All samples were analyzed in triplicate.

The total phenolic compound content in the 50% (v/v) methanolic extract was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent and 9 mL of 7% sodium carbonate (Na2CO3). The mixture (test solution) was kept in a dark place for 90 min [24]. Absorbance was measured against the prepared reagent blank at 760 nm using a Halo DB-20 UV-Vis spectrophotometer. The total phenolic compound content was determined in mg of gallic acid equivalent (GAE) per gram of dry sample weight (mg GAE/g dw).

The total flavonoid content was estimated using the aluminium chloride method [25]. Each plant sample (2.0) was extracted with 70% (v/v) ethanol (0.2 mL) under reflux for 2 h. After cooling, the extract was filtered into a new 50 mL flask. 1 mL of the obtained solution was mixed with 1 mL of aluminum (III) chloride 2%, and 23 mL of 70% ethanol (test solution); the mixture was kept in a dark place for 40 min. Furthermore, the total flavonoid content was measured on a Halo DB-20 UV-Vis spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 410 nm as mg of rutin equivalent (RE) per gram of dry weight sample (mg RE/g dw).

2.5.3 Total Hydroxycinnamic Acids Content

The quantitative determination of hydroxycinnamic acids was carried out by the modified absorption spectrophotometry method in terms of chlorogenic acid equivalents (CAE) per gram of dry weight sample (mg CAE/g dw) on a Halo DB-20 UV-Vis spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 327 nm [26]. The crushed raw material (1.0 g) was extracted with 50 mL of 40% ethanol under reflux for 1 h. After cooling, the extract was filtered, and 1 mL was transferred to a measuring flask, and the volume was brought to 50 mL with 20% ethanol (test solution).

2.5.4 Total Isoflavonoids Content

The total content of isoflavonoids was determined using a previously reported method [22]. The crushed raw material (2.0 g) was extracted with 50 mL of 70% ethanol under reflux for 2 h. After cooling, the extract was filtered, 1 mL was transferred to a measuring flask, and the volume was brought to 25 mL with 70% ethanol (test solution). The total isoflavonoid content was measured as mg of onoside (onogenin 7-O-glucoside) equivalent (OE) per gram of dry weight sample (mg OE/g dw) at a wavelength of 271 nm.

2.6 Chromatographic Determination

2.6.1 Extraction of Plant Material

0.2 ± 0.001 g of raw material was mixed with methanol in a 10 mL round-bottom flask on the ultrasound bath (frequency 38 kHz) (Cambridge, UK, Grant Instruments TM XUB12 Digital) for 30 min. The obtained extract was filtered through 0.45 μm PTFE membrane filters. An aliquot of 20 μL was injected twice into the HPLC system for analysis. The reference compounds were used to prepare standard solutions at a concentration of 1.0 mg/mL in methanol, which were then used for calibration curve for quantitative analysis. The samples were stored at 4°C before use.

The studies were conducted in accordance with the requirements of the State Pharmacopoeia of Ukraine, Article 2.0, “Liquid chromatography” (2.2.29). The compounds were separated using a Nexera X2 LC-30AD HPLC system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), with details provided in the Supporting Information. The detailed chromatographic analysis conditions and the validation characteristics of the method have been previously published [8,27]. The purity of the peaks was checked using a diode array detector coupled to the HPLC system, by comparing the UV spectra of each peak with those of authentic reference compounds and/or by examining the MS spectra (Supporting Information).

2.7 Pharmacological Assay in Vitro

2.7.1 CUPRAC Radical Scavenging Assay

The antioxidant activity was studied using the CUPRAC method spectrophotometrically. The CUPRAC reagent solution was prepared by mixing copper salt (copper (II) chloride dihydrate), neocuproine, and acetate buffer at pH 7 in the ratio 1:1:1. 3 mL of mixed reagent was placed in the cuvette, and 10 μL of sample extract (or Trolox solution) was pipetted into the cuvette. The cuvette was then placed in a dark location for 30 min. Absorbance was measured on a Halo DB-20 UV-Vis spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 450 nm. The measurements were repeated three times. The results of the antioxidant potential were expressed as μM Trolox equivalents per gram of dry weight sample (mg Trolox/g sample) as previously described [28].

HPLC analysis was conducted with a Waters 2695 HPLC system (Waters Corporation, Milford, CT, USA) and a Waters 996 PDA photodiode array detector (Waters Corporation). According to the HPLC procedure [27], after PDA detection, the mobile phase was transferred to a reaction loop with ABTS reagent, which was supplied by a Gilson 305 pump. The ABTS post-column chromatograms were detected at the wavelength of 650 nm using a Waters 2487 UV/VIS detector (Waters Corporation). The parameters of the system with the ABTS solution were set as follows: temperature-50°C; reagent flow rate-0.5 mL/min. The standard antioxidant Trolox (0.3995 μmoL/g) was used for the preparation of the calibration curves [29]. The value was calculated as μmoL Trolox equivalent (TE) for 1 g of sample dry weight using the following formula: TEAC = c × V/m (μmol/g) where ‘c’ is the Trolox concentration in μM established from the calibration curve, ‘V’ is the plant material extract volume in L, and ‘m’ is the weight (precise) in g. The Empower Software Chromatographic Manager System (Waters Corporation, Milford, USA) was used to analyze the data.

2.7.3 Obtaining Dry Extracts for Pharmacology Assays

I. bucharica leaves and bulbs extracts were obtained following the procedure: drying HRM, crushing to a particle size, passing through a sieve with a hole diameter of 3–5 mm, and placing in an extractor. In the extraction (maceration) process, water was used in the ratio of herbal material–extractant as 1:1, and the extraction time was 24 h (twice) until the bioactive compounds were wholly extracted from the herbal material. The extracts were filtered using Whatman no. 40 filter paper and evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure at 40°C (200 rpm) with a rotary evaporator. The crude extracts (15.3 g for leaves and 24.6 g for bulbs) were stored at 4°C in airtight containers. Before conducting bioactivity assays, the extracts were dissolved in DMSO (10% concentration) and then filter-sterilized using a 0.2 μm membrane filter.

2.7.4 Anti-Allergic Activity in RBL-2H3 Cells

A methylthiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT) assay [30] was used to assess the potential toxic effects of the samples on RBL-2H3 cells, as previously described. A β-hexosaminidase release assay was used to determine the degree of A23187-induced and antigen-induced degranulation in RBL-2H3 cells, as previously described [30]. The details of the assays are presented in the Supporting Information.

2.7.5 Anti-Inflammatory Activity in Human Neutrophils

Blood was taken from healthy human donors using a protocol approved by the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital review board. Neutrophils were isolated using the standard procedure described previously [31]. The study involving neutrophils was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (IRB number: 201902217A3). The study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

The inhibition of superoxide anion generation was measured by the reduction of ferricytochrome c, as previously described [30]. Elastase release, representing degranulation from azurophilic granules, was evaluated as described before [30]. The results were expressed as the percent of the initial rate of elastase release in the fMLF/CB-activated drug-free control system. Details in Supporting Information.

A lipid droplet assay was performed according to a previously described method using a BSA-conjugated oleic acid system in Huh7 cells [32]. Briefly, Huh7 cells were seeded in μClear® 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-ONE, Frickenhausen, Germany) and treated with oleic acid and the tested drugs or DMSO for 18 h. Paraformaldehyde was used to fix the cells, which were then stained with 2 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 and 1 μg/mL BODIPY 493/503. High-Content Screening (HCS) was used to capture and analyze images of the nuclei and lipid droplets using an ImageXpress Micro System (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The diameter settings were 8–25 μm for the nuclei and 0.5–2 μm for the lipid droplets.

Nuclear transcription factor (NRF2) activity was evaluated in Huh7 and stable HaCaT/ARE cells expressing an ARE-driven luciferase reporter (pGL4.37) [33]. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates and treated for 18 h. Cell viability was assessed via resazurin fluorescence (530/590 nm), followed by quantification of luciferase activity. Results were normalized to viability and expressed relative to DMSO controls.

2.7.8 Protective Effect of the Extracts against Influenza Virus and Enterovirus

The anti-viral assay was performed by evaluating the cytopathic effects (CPE) of the extracts on cells infected with influenza H1N1 [34] and enterovirus D68 [35]. Briefly, MDCK or RD cells (2 × 104/well) were seeded and infected with virus (9× TCID50) in the presence or absence of extracts for 72 h. Cell survival was quantified by fixing the cells with 4% paraformaldehyde and staining them with 0.1% crystal violet, followed by an optical density measurement.

The protective effect of the samples against human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229) was determined using a previously described method [27]. Huh7 cells were infected with HCoV-229E (9× TCID50) and treated with compounds or vehicle controls. Following incubation at 33°C for 6 days, cell survival was quantified using an MTT assay.

2.7.10 Neuraminidase Activity Assay

Neuraminidase activity was evaluated using a baculovirus displaying surface NA9 (NA9-Bac). The virus was pre-incubated with test samples for 20 min at 37°C prior to the addition of the fluorescent substrate MUNANA. Following a 30-min incubation at ambient temperature, the reaction was terminated with stop solution, and fluorescence was quantified using a microplate reader. Zanamivir served as positive control.

Experiments were routinely conducted as three independent measurements (n = 3), except for the primary bioactivity screening, which was performed as a single measurement (n = 1). Chemical data (mean ± SD, where applicable) were analyzed utilizing LabSolutions and Excel 7.0 according to the State Pharmacopoeia of Ukraine. For datasets with sufficient replicates, bioactivity data (mean ± SEM) were evaluated using GraphPad Prism (v. 5.04/6.0) or SigmaPlot via one-way ANOVA (Tukey’s/Dunnett’s tests) or Student’s t-test or Pearson’s correlation coefficient (Excel). A parametric independent t-test (SAS Studio) was used to compare parameters between leaves and bulbs, where means followed by different letters within the same row indicate statistically significant differences. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

The Iris bucharica, well-adapted to the climate of Ukraine, is promising for local phytotherapy. This study quantifies key phytochemicals in I. bucharica leaves and bulbs to assess their medicinal potential.

3.1 Qualitative Phytochemical Results of Iris bucharica

Table 1 shows the qualitative phytochemical composition of water and ethanol extract of leaves and bulbs of I. bucharica. It was observed that xanthones, flavonoids, tannins, coumarins, saponins, terpenoids, hydroxycinnamic acids, polysaccharides and amino acids were all present, as indicated by their positive test results. In contrast, the alkaloids tested negative, implying they are absent.

Table 1: Qualitative phytochemical composition of I. bucharica extracts.

| Group of BACs | Test | Leaves | Bulbs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xanthones | TLC: n-butanol–acetic acid–water (4:1:2); 15% acetic acid | + | + |

| Flavonoids | AlCl3 test, Ammonia test, Shinoda; cyanidine reaction by Bryant. TLC: n-butanol–acetic acid–water (4:1:2) | +++ | ++ |

| Coumarins | Lactone reaction; formation of azo dye | ++ | + |

| Hydroxycinnamic acids | TLC: n-butanol–acetic acid–water (4:1:2); 15% acetic acid | +++ | +++ |

| Tannins | Ferric chloride; gelatin solution; quinine hydrochloride solution | +++ | ++ |

| Alkaloids | Dragendorff, Mayer’test | − | − |

| Saponins | Foam test, Lieberman-Bourchard | ++ | +++ |

| Amino acids | 0.25% Ninhydrin reaction | +++ | +++ |

| Proteins | Xantoproteic assay | ++ | + |

| Triterpenoids | Salkowski assay | + | + |

| Polysaccharides | Molisch reaction | ++ | +++ |

Understanding the qualitative phytochemical composition of I. bucharica raw materials is essential for assessing their therapeutic potential. Compounds such as xanthones, flavonoids, and tannins are associated with valuable pharmacological activities, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial effects [36]. In addition, confirmation of the absence of potentially toxic compounds such as alkaloids indicates safety, and establishing the phytochemical profile ensures quality control for consistent efficacy in medicinal applications [10]. This information also supports targeted extraction, enabling researchers to select suitable solvents and methods for effective isolation of these compounds.

3.2 Quantitative Phytochemical Results

The quantitative phytochemical analysis of I. bucharica leaves and bulbs HRM extracts revealed distinct concentrations of key bioactive compounds in both plant parts (Table 2). The leaves exhibited higher levels of total flavonoid content (1.40 mg GAE/g dw) and total hydroxycinnamic acid content (1.26 mg CAE/g), suggesting a strong antioxidant potential. Comparatively, the bulbs were richer in total phenolic compounds content (5.74 mg GAE/g dw), indicating possible anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties. These results highlight the different phytochemical profiles between leaves and bulbs, suggesting that each part of the Iris plant may serve unique therapeutic roles, with potential applications in developing targeted herbal treatments based on the specific bioactive constituents.

Table 2: Physicochemical parameters and total polyphenolic content in the leaves and bulbs of Iris bucharica (mean ± SD, n = 3).

| Total Content of BACs | Leaves | Bulbs |

|---|---|---|

| Phenolic compounds, mg GAE/g | 4.87 ± 0.09b | 5.74 ± 0.10a |

| Hydroxycinnamic acids, mg CAE/g | 1.26 ± 0.02a | 0.75 ± 0.01b |

| Flavonoids, mg RE/g | 1.40 ± 0.02a | 0.57 ± 0.01b |

| Isoflavonoids, mg OE/g | 2.07 ± 0.12b | 3.34 ± 0.15a |

| Loss on drying, % | 5.19 ± 0.09b | 6.13 ± 0.11a |

| The total ash, % | 3.25 ± 0.12b | 4.05 ± 0.10a |

| The ash content insoluble in hydrochloric acid, % | 2.15 ± 0.05ns | 2.23 ± 0.07ns |

Physicochemical parameters, including loss on drying, total ash value, and acid-insoluble ash value, were determined for I. bucharica raw materials (Table 2). These parameters are commonly used in pharmacognostic studies as indicators of composition and purity, providing a reference for future standardisation and identification of this plant [21].

Following the initial phytochemical analysis, the next phase of the study involved determining the chemical profile of phenolic compounds in Iris leaves and bulbs using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). This method provides a detailed profile of individual phenolic constituents, allowing precise quantification and identification of specific compounds that contribute to the plant’s bioactivity, such as flavonoids and hydroxycinnamic acids [37].

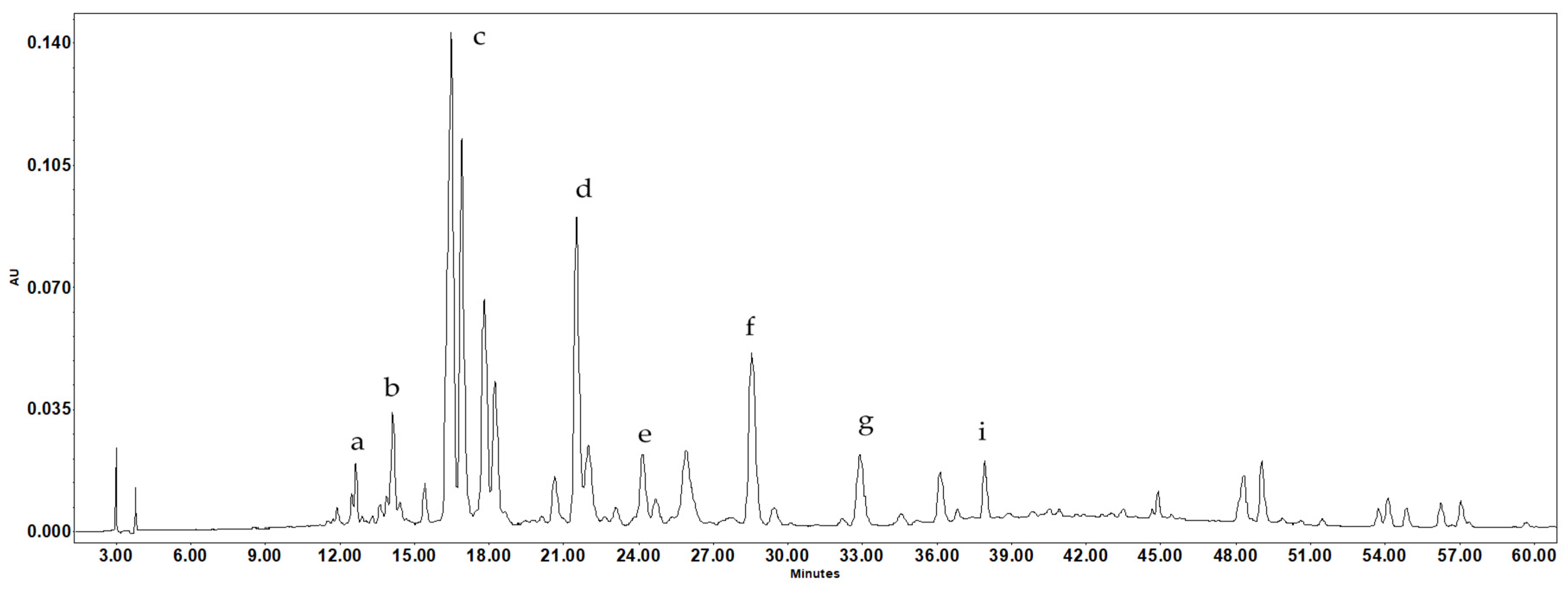

Phenolic compounds were extracted from Iris leaves and bulbs in an ultrasonic bath for 30 min without additional heating. Chromatographic separation of the extracts was performed using a Shimadzu Nexera X2 LC-30AD HPLC system equipped with an ACE C18 column (Fig. 3). The solvent system consisted of 0.1% acetic acid in water with gradient elution using acetonitrile, increasing from 5% to 95%.

Figure 3: Typical HPLC chromatogram of the methanol extract of Iris bucharica leaves at 350 nm. Peaks: a—chlorogenic acid; b—vanillic acid; c—isoorientin; d—ferulic acid; e-hyperoside; f—guaijaverin; g—cosmosiin; i—afzelin.

This study describes the phenolic composition of I. bucharica leaves and bulbs (Table 3, Fig. 3) and the composition of phenolic compounds in dry extracts from these raw materials (Table 4). Given the increasing demand for natural ingredients in medicines and the focus on creating “soft” herbal formulations, identifying and studying new plants rich in phenolic compounds represents an important research direction.

The chemical composition of I. bucharica showed the presence of substances characteristic of the genus Iris, as well as substances specific to this species. In the methanol extract of I. bucharica leaves, 13 phenolic compounds were identified and quantified for the first time, including chlorogenic acid, neochlorogenic acid, vanillic acid, catechin, epicatechin, ferulic acid, vitexin (apigenin 8-C-glucoside), hyperoside (quercetin-3-O-L-arabinoside), nicotiflorin (kaempferol-3-O-D-rutinoside), cosmosiin (apigenin 7-O-D-glucoside), and afzelin (kaempferol-3-O-L-rhamnoside). The dominant components in the leaves are guaijaverin (quercetin-3-O-L-arabinoside) and isoorientin. The leaves also contain significant amounts of vanillic acid and nicotiflorin, with flavonoids being the predominant class of compounds.

(–)-Embinin, a potent antioxidant flavonoid previously isolated from the flowers and leaves of Iris persica [16], is structurally related to compounds such as isoorientin and guaijaverin. These latter compounds have been found in the leaves of I. bucharica. Similar flavonoid structures suggest that Iris chemistry is tied to its evolutionary lineage. This shared ancestry likely explains why these species all show potent antioxidant activity.

In the bulbs, the following compounds were found: tectoridin, cosmosiin, apigenin, nigricin, iristectorigenin B, germanaism B (nigricin-4′-D-glucoside), irigenin, chlorogenic acid, ferulic acid, and biochanin A (5,7-dihydroxy-4-methoxyisoflavone). Isoflavonoids are the main compounds present in the bulbs, with tectoridin and germanaism B being the dominant compounds. Additionally, high content of flavonoid apigenin was also detected in methanolic extract of bulbs.

Table 3: Quantitative content of identified components of leaves and bulbs of Iris bucharica, as well as their chromatographic and UV data.

| tR (min) | UV λmax (nm) | Compound | Leaves | Bulbs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9.41 | 217, 234, 325 | Neochlorogenic acid | 0.01 ± 0.01a | -b |

| 11.88 | 280 | Catechin | 0.03 ± 0.01a | -b |

| 11.89 | 218, 241, 327 | Chlorogenic acid | 0.15 ± 0.02a | 0.03 ± 0.01b |

| 14.00 | 219, 260, 293 | Vanillic acid | 0.56 ± 0.31a | -b |

| 14.18 | 240, 318, 257, 365 | Mangiferin | 0.04 ± 0.01a | 0.02± 0.01b |

| 14.65 | 280 | Epicatechin | 0.05 ± 0.02a | -b |

| 16.70 | 269, 349 | Isoorientin | 3.25 ± 0.04a | -b |

| 20.01 | 227, 309 | p-Coumaric acid | 0.58 ± 0.01a | -b |

| 22.75 | 218, 236, 323 | Ferulic acid | 1.15 ± 0.01a | 0.80 ± 0.01b |

| 22.86 | 269, 215 | Vitexin | 0.02 ± 0.02a | -b |

| 23.89 | 255, 353 | Hyperoside | 1.07 ± 0.10a | -b |

| 28.55 | 254, 266, 352 | Guaijaverin | 3.26 ± 0.06a | -b |

| 29.90 | 263, 328 | Tectoridin | -b | 1.60 ± 0.03a |

| 30.53 | 266, 348 | Nicotiflorin | 0.35 ± 0.22a | -b |

| 33.49 | 237, 266 | Cosmosiin | 1.48 ± 0.25a | 0.34 ± 0.01b |

| 37.91 | 272, 361 | Afzelin | 0.83 ± 0.10a | -b |

| 41.03 | 260, 322 | Germanaism B | 0.15 ± 0.01b | 1.57 ± 0.30a |

| 45.91 | 260, 330 | Kikkalidone | 0.08 ± 0.02b | 0.15 ± 0.04a |

| 46.07 | 259, 332 | Genistin | -b | 0.08 ± 0.01a |

| 47.90 | 237, 267, 337 | Apigenin | -b | 2.68 ± 0.05a |

| 49.15 | 218, 265 | Iristectorigenin B | 0.06 ± 0.01b | 0.08 ± 0.30a |

| 49.50 | 262, 322 | Nigricin | -b | 0.03 ± 0.22a |

| 50.03 | 264, 218 | Irigenin | 0.12 ± 0.02b | 0.85 ± 0.02a |

| 60.69 | 196, 260 | Biochanin A | 1.18 ± 0.02a | 0.19 ± 0.00b |

| 61.25 | 259, 322 | Irisolidone | 0.86 ± 0.03a | 0.05 ± 0.01b |

In the leaves of I. bucharica, flavonoids are the dominant group of compounds, with a total identified content of 10.34 mg/g, followed by isoflavonoids and hydroxycinnamic acids at 2.45 mg/g and 1.89 mg/g, respectively. In the bulbs, isoflavonoids are the predominant compounds, with a total identified content of 4.60 mg/g, while flavonoids are slightly lower at 3.02 mg/g, as determined by the HPLC method (Table 3). A comparison of the total phenolic content shows that the leaves contain 15.28 mg/g, whereas the bulbs contain 8.47 mg/g.

Evaluation of the quantitative content of individual compounds revealed significant amounts of chlorogenic acid (0.15 mg/g in leaves) and kaempferol derivatives, in particular nicotiflorin and afzelin. This confirms that I. bucharica can be considered a source of similar bioactive compounds.

Of note is the high content of isoorientin (3.25 mg/g) and guaijaverin (3.26 mg/g) in I. bucharica leaves, which are rarely described in other Iris species but are known to be effective antioxidants and inflammation inhibitors [38]. Their presence may explain the more pronounced activity of leaves compared to bulbs in antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-allergy tests, described in the current study.

The observed profile of isoflavonoids and phenolic acids aligns I. bucharica with the chemotaxonomic signatures of established medicinal species, such as I. germanica and I. florentina [39]. These results also complement phytochemical profiling of Ukrainian Iris rhizomes (I. hungarica, I. variegata, I. pallida, I. sibirica), where isoflavonoids such as irigenin, nigricin (irisolone), and tectoridin serve as pharmacologically distinct markers [27]. Aligning with the chemotaxonomic significance of germanaism B and kikkalidone in I. variegata and I. hungarica, the conserved presence of hydroxycinnamic acids and mangiferin further substantiates the genus’s recognized anti-inflammatory and anti-viral therapeutic value.

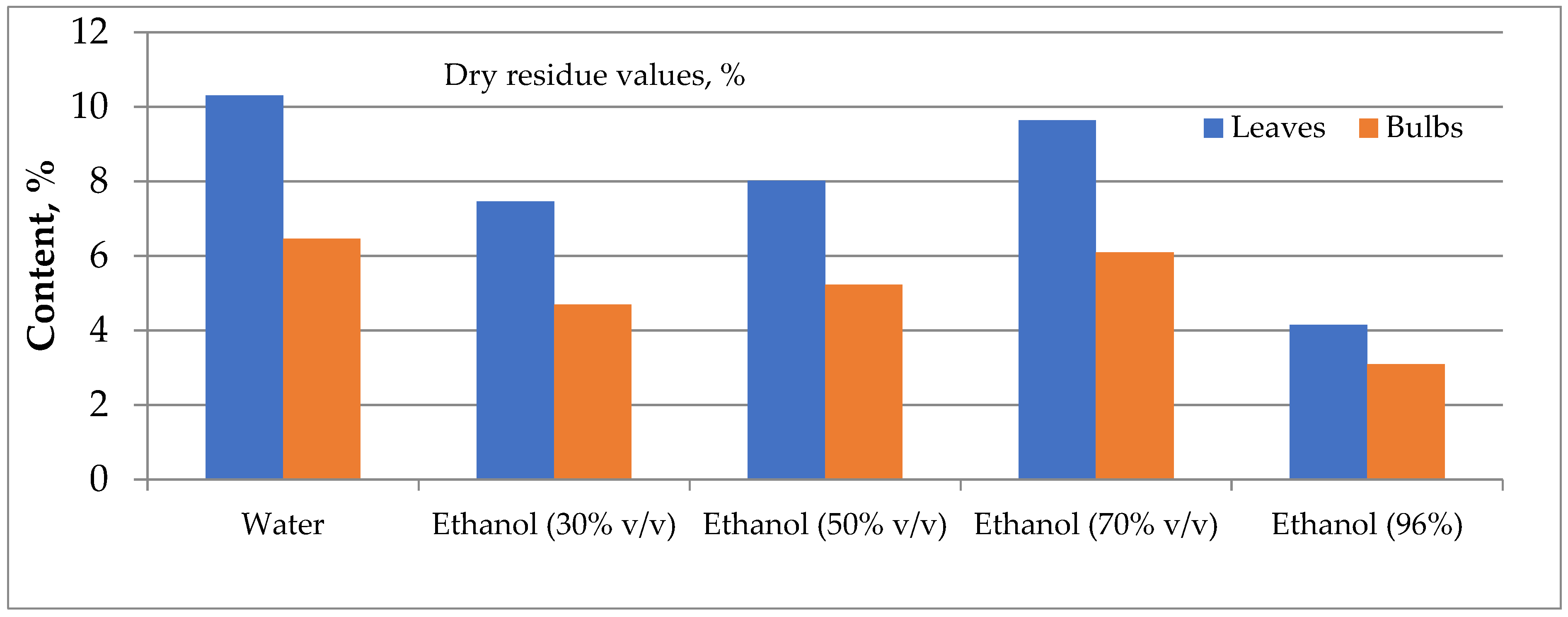

3.3 Optimal Solvent Selection for Pharmacological Screening of Dry Extracts

Comparative analysis of the content of extractive compounds in I. bucharica HRM showed that purified water and 70% ethanol extracted the maximum amount of compounds (Fig. 4). For leaves and bulbs, the yield in water was 10.31% and 6.46%, respectively. For 70% ethanol, the yield was 9.64% for leaves and 6.10% for bulbs.

Figure 4: Comparative analysis of the content of extractive compounds of Iris bucharica.

Water was chosen as the optimal solvent for obtaining dry extracts from Iris leaves and bulbs for the primary pharmacological screening [40]. This selection was based on water’s ability to maximise the extraction of phenolics while maintaining environmental safety. A preliminary study of the chemical composition of water extracts was conducted to develop optimal conditions for obtaining dry extracts with specific pharmacological effects. The composition of these extracts was analyzed using HPLC, and the resulting data are presented in Table 4.

This approach ensures the extraction of bioactive compounds, especially phenolics, which are key to the observed pharmacological activities of the Iris dry extracts. HPLC fingerprinting identified mangiferin, nigricin, genistin, tectoridin, biochanin A, and cinnamic acids in the plant extracts. The bulbs’ dry extract of I. bucharica was rich in iristectorigenin B (1.83 ± 0.03 mg/g) and tectoridin (1.60 ± 0.01 mg/g). At the same time, the leaves were dominated by isoorientin (10.11 ± 0.21 mg/g), guaijaverin (5.24 ± 0.10 mg/g), and ferulic acid (3.07 ± 0.05 mg/g). According to Unver et al. [15], trans-ferulic acid (0.047 g/kg) in I. persica, a closely related species, was also high compared to other identified compounds.

Table 4: Quantitative content of identified components (mg/g) in the dry water extracts of Iris bucharica leaves and bulbs.

| Compound | RT, min | Leaves | Bulbs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mangiferin | 14.18 | 0.92 ± 0.02a | 0.35 ± 0.08b |

| Isoorientin | 16.74 | 10.11 ± 0.21a | -b |

| p-Coumaric acid | 20.01 | 1.04 ± 0.02a | -b |

| Ferulic acid | 23.09 | 3.07 ± 0.05a | 1.33 ± 0.02b |

| Guaijaverin | 28.55 | 5.24 ± 0.10a | -b |

| Tectoridin | 30.03 | 0.16 ± 0.01b | 1.60 ± 0.01a |

| Cosmosiin | 33.49 | 1.66 ± 0.04a | -b |

| Germanaism B | 41.08 | 0.46 ± 0.01a | 0.22 ± 0.01b |

| Kikkalidone | 45.91 | 0.30 ± 0.01ns | 0.34 ± 0.01ns |

| Genistin | 46.07 | -b | 0.52 ± 0.01a |

| Apigenin | 47.90 | 0.05 ± 0.00a | -b |

| Iristectorigenin B | 49.15 | 0.21 ± 0.01b | 1.83 ± 0.03a |

| Nigricin | 49.50 | -b | 0.39 ± 0.00a |

| Irigenin | 50.03 | 0.92 ± 0.02a | 0.68 ± 0.01b |

| Biochanin A | 61.18 | 1.16 ± 0.02a | 0.19 ± 0.01b |

| Irisolidone | 61.24 | 1.36 ± 0.03a | 0.27 ± 0.01b |

Further research is needed to optimise the operating parameters (such as extraction time, temperature, pH, moisture content, and particle size) for the “green” water extraction of I. bucharica leaves and bulbs. These factors influence the interaction between the dissolved substances and the solvent [41]. It’s essential to note that green extraction is a pioneering approach designed to safeguard the environment and human health while improving the sustainability and cost-effectiveness of the industry.

3.4 Pharmacological Evaluation in Vitro

The next aim of the study was to evaluate the different pharmacological activities of water extracts derived from Iris leaves and bulbs. The preliminary bioactivity screening of Iris bucharica leaves and bulbs revealed a promising effect in antioxidant and anti-allergic assays, while other bioactivities showed lower potency (Table 5).

Table 5: The results of the preliminary screening data of Iris bucharica leaves and bulbs dry extract.

| Sample | Relative NRF2 Activitya in HacaT Cellb (%, Mean ± SD) | Relative NRF2 Activitya in Huh7 Cellc (%, Mean ± SD) | Neuraminidase NA9 Inhibition Activityd (%, Mean ± SD) | Lipid Droplet Inhibition Activitye (%, Mean ± SD) | Inhibition of A23187-Induced Degranulation Assay, RBL-2H3 Cellsf (%) | Inhibition of Antigen-Induced Degranulation Assay, RBL-2H3 Cellsf (%) | Protective Activity Against Influenza H1N1, MDCK Cellsg | Protective Activity Against Enterovirus D68, RD Cellsg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iris leaves (H2O) | 110.8 | 113.2 | 9.0 ± 1.2 | 70 ± 16.7 | 21 | 19 | inactive | inactive |

| Iris bulbs (H2O) | 135.2 | 111.4 | −3.1 ± 0.2 | 89.6 ± 15.7 | 23 | 19 | inactive | Inactive |

| TBHQh | 684.3 ± 53.3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Luteolini | – | 23.8 ± 0.3 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Zanamivirj | – | – | 96.8 ± 0.2 | – | – | – | – | – |

| TCk | – | – | – | 16.3 ± 0.2 | – | – | – | – |

3.4.1 Anti-Viral and Anti-Neuraminidase Activity

There is a lack of studies on the anti-viral and anti-neuraminidase activities of I. bucharica extracts, while different Iris species have been reported to possess antiviral properties [42]. To assess the protective effects of these extracts, established cell models were utilized: Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) epithelial cells infected with the H1N1 influenza virus (A/WSN/33), and rhabdomyosarcoma (RD) cells infected with enterovirus D68 (500 μg/mL, Table 5).

The results showed that neither the Iris dry extracts of leaves nor bulbs exhibited significant anti-viral effects against the H1N1 influenza virus, enterovirus D68, or neuraminidase N9. In particular, the leaves demonstrated only minimal inhibition of neuraminidase activity (9% at a concentration of 100 μg/mL) with zanamivir used as a positive control. These results highlight the limited anti-viral activity of I. bucharica dry extracts under the tested conditions, suggesting the need for further investigation into other potential pharmacological properties.

Additionally, both the leaves and bulbs extracts were evaluated for anti-allergic effects in RBL-2H3 cells, and in the first test, both samples were found to be non-toxic to RBL-2H3 cells at 200 μg/mL (weak toxicity was detected at 500 μg/mL). In the preliminary screening at 200 μg/mL, the leaves and bulbs extracts demonstrated mild anti-allergic activity, inhibiting 21% and 23% of degranulation induced by A23187, and 19% and 19% triggered by antigen, respectively (Table 5). Notably, the I. bucharica bulbs extract (100 μg/mL) showed significant anti-allergic inhibitory effects, with 20.0% inhibition of A23187-induced degranulation and 24.3% of antigen-induced degranulation (Table 6). While isoorientin was identified as a major constituent of I. bucharica leaves, it remained inactive at 100 μM. This suggests that other components may be responsible for the activity of the extract, althought potential synergistic effects between multiple constituents cannot be excluded. A positive control, dexamethasone, inhibited 65.7% and 66.3% of A23187- and antigen-induced degranulation, respectively. Previously, simple phenolic ferulic acid [43], flavonoids, such as apigenin [44], and flavonoid glycosides, such as guajaverin [45], aglycon of tectoridin [46], but not cosmosiin, were reported to exert anti-allergic activities in different models and may contribute to the activity observed in I. bucharica bulbs.

Table 6: Anti-allergic activity of Iris bucharica bulbs, leaves, and the major compound isoorientin.

| Sample Description | % Viability, RBL-2H3a | % Inhibition of A23187-Induced Degranulationb | % Inhibition of Antigen-Induced Degranulationc | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 μg/mL | 10 μg/mL | 100 μg/mL | 10 μg/mL | 100 μg/mL | |||||||||||||

| Iris leaves (H2O) | 98.3 | ± | 0.9 | 0.3 | ± | 0.3 | 7.7 | ± | 1.7 | 8.0 | ± | 8.0 | 8.0 | ± | 4.0 | ||

| Iris bulbs (H2O) | 92.7 | ± | 4.3 | 2.0 | ± | 2.0 | 20.0 | ± | 2.0 | * | 5.3 | ± | 4.4 | 24.3 | ± | 5.5 | * |

| isoorientind | 99.3 | ± | 0.5 | 0.0 | ± | 0.0 | 3.0 | ± | 2.4 | 0.0 | ± | 0.0 | 2.0 | ± | 0.0 | ||

3.4.3 Anti-Inflammatory Activity

The respiratory burst and degranulation of neutrophils are essential for maintaining human health, but must be well-regulated to prevent the development of chronic and autoimmune diseases. We evaluated the effect of I. bucharica samples on superoxide anion generation and elastase release triggered by fMLF in CB-primed human neutrophils (Table 7). I. bucharica dry leaves extract exhibited a significant, though moderate, anti-inflammatory effect, inhibiting superoxide anion formation by 31% at a 10 μg/mL concentration. The leaves extract also demonstrated 27% inhibition in elastase release assays, suggesting its potential to suppress neutrophilic inflammation.

Table 7: Effects of Iris bucharica leaves extract on superoxide anion generation and elastase release in FMLP/CB-induced human neutrophils.

| Sample Description | Superoxide Anion Generation | Elastase Release | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inh % (10 μg/mL) | Inh % (10 μg/mL) | |||||

| Iris leaves (H2O) | 30.98 | ± | 1.53*** | 27.04 | ± | 4.94** |

3.4.4 Antioxidant Capacity and Lipid-Lowering Effects

Previous studies have shown that plant extracts rich in phenolic compounds can influence the antioxidant capacity of cells, including the expression of NRF2 [47]. In the NRF2 assay conducted on normal HaCaT skin cells, the I. bucharica bulbs extract increased NRF2 activity, a key marker of the protective antioxidant response, by 35% (Table 5). However, the extracts did not affect NRF2 activity in Huh7 liver cancer cells at 100 μg/mL (leaves 113.2% and bulbs 111.4%). Therefore, I. bucharica bulbs may have a specific mild enhancing effect on the antioxidant capacity, which is selective to normal cells. This correlates well with NRF2 enhancing activities of major compounds identified in crude extracts, such as flavonoid glycosides tectoridin [48] and isorientin [49] or simple phenolic ferulic acid [50]. Additionally, Iris bucharica leaves extract reduced lipid droplet formation by 30% at a 100 μg/mL concentration. These results indicate a modest activity with potential relevance to metabolic disorders such as obesity or NAFLD.

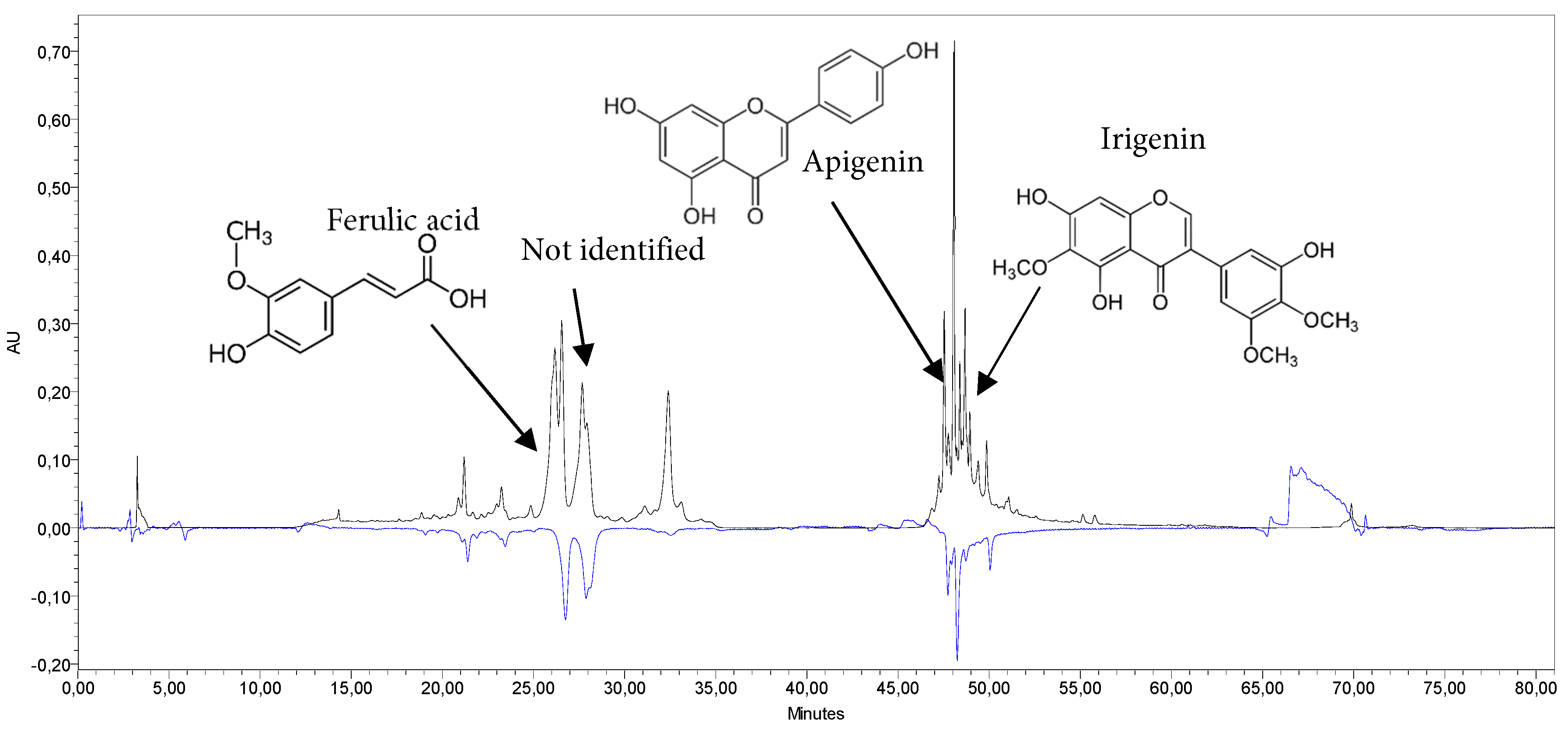

3.4.5 Antioxidant Activity Using the ABTS Post-Column Assay

The study of the antioxidant activity of I. bucharica extracts revealed significant antioxidant potential, especially in the leaves. By the CUPRAC method, the I. bucharica leaves extract demonstrated potent antioxidant activity with a value of 0.244 mg/mL (p < 0.05), comparable to Trolox standards (0.22–1.54 mg/mL), suggesting that phenolic compounds are key contributors. The extract of the bulbs exhibited moderate antioxidant activity at a concentration of 0.20 mg/mL. Using the HPLC-ABTS method, the I. bucharica leaves extract exhibited stronger antioxidant capacity (TEAC 672.32 μmol/g) compared to the bulbs extract (TEAC 11.91 μmoL/g) (Table 8). The leaves extract showed 11 active compounds, whereas the bulbs extract had 4 compounds. Among the profiled phenolic compounds, guaijaverin, apigenin, ferulic acid and irigenin emerged as the predominant contributors to antioxidant activity, surpassing other identified compounds, such as gallic acid, vanillic acid and hyperoside. These compounds, known for their high oxidation-reduction potential, act as hydrogen donors and quenchers of singlet oxygen [51]. The higher activity in the leaves extract is likely due to the greater content of these identified and other unidentified substances. Furthermore, a mild, statistically significant positive correlation (p < 0.05) was observed between the phenolic compound content and radical scavenging activity (Table S1).

Table 8: Radical scavenging activity of individual compounds of Iris bucharica dry extracts expressed as TEAC (μmol/g) using ABTS post-column analysis.

| No. | Compounds | Retention Time | Leaves | Bulbs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Not identified | 5.89 | 22.17 ± 0.39a | -b |

| 2 | Not identified | 8.46 | -b | 2.01 ± 0.04a |

| 3 | Isoorientin | 19.07 | 3.84 ± 0.07a | -b |

| 4 | p-Coumaric acid | 21.10 | 4.44 ± 0.08a | -b |

| 5 | Not identified | 21.39 | 19.79 ± 0.35a | -b |

| 6 | Ferulic acid | 23.44 | 25.40 ± 0.45a | 5.65 ± 0.10b |

| 8 | Not identified | 26.76 | 177.52 ± 3.12a | -b |

| 9 | Guaijaverin | 27.89 | 208.83 ± 3.67a | -b |

| 10 | Not identified | 36.58 | -b | 2.15 ± 0.04a |

| 11 | Not identified | 43.25 | -b | 2.10 ± 0.04a |

| 12 | Apigenin | 47.74 | 64.57 ± 1.14a | -b |

| 13 | Not identified | 48.25 | 111.74 ± 1.96a | -b |

| 14 | Iristectorigenin B | 48.73 | 11.35 ± 0.20a | -b |

| 15 | Irigenin | 50.06 | 22.67 ± 0.40a | -b |

| Total content | 672.32a | 11.91b |

Analysis of the dry water extracts revealed that Iris leaves (Fig. 5) exhibit significantly stronger antioxidant activity compared to the bulbs (see statistical significance, with the letter “a” indicating a higher content). This superior activity is likely attributed to the leaves’ higher phenolic content, a class of compounds well-documented for their antioxidant properties.

Figure 5: HPLC-ABTS chromatogram of Iris bucharica leaves extract (H2O) at 339 nm (HPLC, black) and 650 nm (ABTS, blue), and the main bioactive compounds.

3.4.6 Integrative Assessment of Bioactivity and Phenolic Composition

While Iris bucharica is primarily utilized as an ornamental plant, its phytochemical profile suggests therapeutic potential similar to that of related species, like I. germanica, I. florentina and I. pallida (Orris root), which are traditionally employed as diuretics and anti-inflammatory poultices [39]. Guided by this ethnopharmacological context, we linked the observed chemical composition of I. bucharica to specific bioactivities, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-virus and anti-allergic properties. These findings, combined with existing literature [11], suggest that the high phenolic content in I. bucharica leaves contributes significantly to antioxidant effects, NRF2 activation, the inhibition of neutrophil superoxide anion production, and degranulation in mast cells.

Comparative data from related Ukrainian species corroborate the observed immunomodulatory potential. For instance, rhizome extracts of I. hungarica and I. variegata have previously demonstrated significant inhibition of neutrophil superoxide anion generation (41.0–45.7%) and antigen-induced mast cell degranulation (27.0–46.7%) [27]. Mechanistically, these effects are driven by specific phenolic constituents. Apigenin has exhibited superior anti-neutrophilic efficacy, up to 100% inhibition of both superoxide generation and elastase release, while quercetin significantly reduced elastase release (61.9%) [27]. Additionally, the xanthone mangiferin specifically suppressed superoxide production (65.9%), likely via antioxidant mechanisms. These bioactivities are structurally attributed to the C-4′, C-5, and C-7 hydroxyl substituents on the flavonoid core [42]. Consequently, our combined data confirm that phenolic compounds, particularly isoflavones such as irisolidone and simple flavones like apigenin, or hydroxycinnamic acids like ferulic acid, are responsible for the potent anti-inflammatory, anti-allergic, antioxidant, and anti-viral activities observed across the genus (Table S2).

Regarding I. bucharica, the bulbs displayed a notable inhibitory tendency in anti-allergic assays at 100 μg/mL, while leaves in anti-inflammatory assays at 10 μg/mL. However, higher concentrations may be required to achieve maximal inhibition rates. These findings highlight the potential of Iris extracts as therapeutic agents targeting inflammation and allergic responses. Future studies will aim to isolate the specific active phenolics responsible for these effects in I. bucharica and elucidate their precise mechanisms in anti-allergic models.

This study provides the first comprehensive analysis of phenolic compounds in Iris bucharica leaves and bulbs. Using an HPLC-UV-based method, 21 phenolic compounds were identified in the leaves and 14 in the bulbs, establishing initial quality control markers for this species. Leaves extracts exhibited significant antioxidant activity, while both leaves and bulb extracts showed mild anti-allergic effects. High concentrations of guaijaverin, isoorientin, cosmosiin, and ferulic acid likely contribute to these bioactivities.

These findings demonstrate that I. bucharica is a promising source of bioactive compounds with potential applications in managing oxidative stress and allergy-related conditions, aligning with the study’s objectives to explore its pharmacological potential. Limitations of the study that would need to be addressed in future studies include the absence of in vivo validation and a lack of mechanism-related studies. Future research should also focus on assessing the bioavailability and optimising extraction methods to fully explore the therapeutic potential of I. bucharica.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This study was supported by grants from the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC), Taiwan (NSTC 114-2320-B-037-020-MY3, 113-2320-B-037-023, and 112-2320-B-037-012 granted to M.K.; 113-2321-B-255-001, 113-2321-B-182-003, 112-2321-B-182-003, 112-2321-B-255-001, 111-2320-B-255-006-MY3, and 111-2321-B-255-001 granted to T.L.H.), and Kaohsiung Medical University Research Foundation [KMU-Q113011 awarded to M.K. and KMU-M114020 awarded to B.H.C.], and NSYSU-KMU joint research project (NSYSU-KMU-114-P16) awarded to M.K.

Author Contributions: Olha Mykhailenko: conceptualization, data curation, methodology, resources, writing—original draft preparation; Liudas Ivanauskas: investigation; Michal Korinek: investigation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing; Zigmantas Gudžinskas: resources, writing—review and editing; Riong Seulina Panjaitan: data analysis; Chia-Hung Yen: methodology and data analysis, funding; Chung-Fan Hsieh: methodology and data analysis; Tsong-Long Hwang: methodology and data analysis, funding. Bing-Hung Chen: methodology; Liudas Ivanauskas: project administration; Victoriya Georgiyants: project administration. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available within the article or its Supplementary Materials.

Ethics Approval: The study involving neutrophils was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (IRB number: 201902217A3). The study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Writtenin formed consent was obtained from each participant.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2026.074209/s1.

References

1. Mahato D , Mahto H , Kumari S . Medicinal and aromatic plant cultivation and sustainable development. In: Industrial crops improvement. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2025. p. 135– 53. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-75937-6_8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Gasmi A , Mujawdiya PK , Noor S , Lysiuk R , Darmohray R , Piscopo S , et al. Polyphenols in metabolic diseases. Molecules. 2022; 27( 19): 6280. doi:10.3390/molecules27196280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Lutz M , Fuentes E , Ávila F , Alarcón M , Palomo I . Roles of phenolic compounds in the reduction of risk factors of cardiovascular diseases. Molecules. 2019; 24( 2): 366. doi:10.3390/molecules24020366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Amin HIM , Hussain FHS , Najmaldin SK , Thu ZM , Ibrahim MF , Gilardoni G , et al. Phytochemistry and biological activities of Iris species growing in Iraqi Kurdistan and phenolic constituents of the traditional plant Iris postii. Molecules. 2021; 26( 2): 264. doi:10.3390/molecules26020264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wilson CA . Subgeneric classification in Iris re-examined using chloroplast sequence data. Taxon. 2011; 60( 1): 27– 35. doi:10.1002/tax.601004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wilson CA , Padiernos J , Sapir Y . The royal irises (Iris subg. Iris sect. Oncocyclus): plastid and low-copy nuclea data contribute to an understanding of their phylogenetic relationships. Taxon. 2016; 65( 1): 35– 46. doi:10.12705/651.3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Crespo MB , Martínez-Azorín M , Mavrodiev EV . Can a rainbow consist of a single colour? A new comprehensive generic arrangement of the ‘Iris sensu latissimo’ clade (Iridaceae), congruent with morphology and molecular data. Phytotaxa. 2015; 232( 1): 1. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.232.1.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Mykhailenko O , Gudžinskas Z , Kovalyov V , Desenko V , Ivanauskas L , Bezruk I , et al. Effect of ecological factors on the accumulation of phenolic compounds in Iris species from Latvia, Lithuania and Ukraine. Phytochem Anal. 2020; 31( 5): 545– 63. doi:10.1002/pca.2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Chandni , Ahmad SS , Saloni A , Bhagat G , Ahmad S , Kaur S , et al. Phytochemical characterization and biomedical potential of Iris kashmiriana flower extracts: a promising source of natural antioxidants and cytotoxic agents. Sci Rep. 2024; 14( 1): 24785. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-58362-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Wang H , Chen Y , Wang L , Liu Q , Yang S , Wang C . Advancing herbal medicine: enhancing product quality and safety through robust quality control practices. Front Pharmacol. 2023; 14: 1265178. doi:10.3389/fphar.2023.1265178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Jaegerova T , Viktorova J , Zlechovcova M , Vosatka M , Kastanek P , Hajslova J . Investigation of secondary metabolites and their bioactive potential in various Iris species and cultivars grown under different cultivation conditions. ACS Omega. 2025; 10( 43): 51256– 71. doi:10.1021/acsomega.5c06354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Xie GY , Zhu Y , Shu P , Qin XY , Wu G , Wang Q , et al. Phenolic metabolite profiles and antioxidants assay of three Iridaceae medicinal plants for traditional Chinese medicine “She-gan” by on-line HPLC-DAD coupled with chemiluminescence (CL) and ESI-Q-TOF-MS/MS. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2014; 98: 40– 51. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2014.05.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Mykhailenko O , Ivanauskas L , Bezruk I , Lesyk R , Georgiyants V . Comparative investigation of amino acids content in the dry extracts of Juno bucharica, Gladiolus hybrid zefir, Iris hungarica, Iris variegata and Crocus sativus raw materials of Ukrainian flora. Sci Pharm. 2020; 88( 1): 8. doi:10.3390/scipharm88010008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Arifkhodzhaev KA , Tukhtasinova MM , Khamidkhodzhaev SA . Polysaccharides of Iridaceae. III. Amounts of carbohydrates in plants of the genus Crocus and Juno. Chem Nat Compd. 1986; 22( 4): 472– 3. doi:10.1007/BF00579828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Unver T , Uslu H , Gurhan I , Goktas B . Screening of phenolic components and antimicrobial properties of Iris persica L. subsp. persica extracts by in vitro and in silico methods. Food Sci Nutr. 2024; 12( 9): 6578– 94. doi:10.1002/fsn3.4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Amin HIM , Hussain FHS , Maggiolini M , Vidari G . Bioactive constituents from the traditional Kurdish plant Iris persica. Nat Prod Commun. 2018; 13( 9): 1934578X1801300907. doi:10.1177/1934578x1801300907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. El-Emary NA , Kobayashi Y , Ogihara Y . Two isoflavonoids from the fresh bulbs of Iris tingitana. Phytochemistry. 1980; 19( 8): 1878– 9. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)83844-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Farag SF , Kimura Y , Ito H , Takayasu J , Tokuda H , Hatano T . New isoflavone glycosides from Iris spuria L. (Calizona) cultivated in Egypt. J Nat Med. 2009; 63( 1): 91– 5. doi:10.1007/s11418-008-0291-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Pavlova MA . The results of introduction of species of Juno Tratt. genus and the prospects for their use in the greenery planting in the South-East of Ukraine. Ind Bot. 2011; 11: 212– 6. [Google Scholar]

20. Sikyra AJ . Introduction to the genus Juno Tratt. of flora of Central Asia and Kazakhstan in Ukraine. (Інтродукція видів роду Juno Tratt. флори Середньої Азії та Казахстану в Україні). Kyiv, Ukraine: Bulletin of Kyiv University “Introduction and Conservation of Plant Diversity”; 1999 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. p. 19– 20. (In Ukrainian). Available from: http://www.nbg.kiev.ua/collections_expositions/index.php?SECTION_ID=234. [Google Scholar]

21. Ukrainian Scientific Pharmacopoeial Centrefor Quality of Medicines. State pharmacopoeia of Ukraine. 2nd ed. Kharkiv, Ukraine: State Enterprise Ukrainian Scientific Pharmacopoeial Centrefor Quality of Medicines; 2015. [Google Scholar]

22. Mykchailenko OO , Kovalyov MV . Phenolic compounds of the genus Iris plants (Iridaceae). Ceska Slov Farm. 2016; 65( 2): 70– 7. doi:10.36290/csf.2016.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Mapfumari S , Nogbou ND , Musyoki A , Gololo S , Mothibe M , Bassey K . Phytochemical screening, antioxidant and antibacterial properties of extracts of Viscum continuum E. Mey. ex. Sprague, a South African mistletoe. Plants. 2022; 11( 16): 2094. doi:10.3390/plants11162094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Rodríguez-Roque MJ , Del-Toro-Sánchez CL , Chávez-Ayala JM , González-Vega RI , Pérez-Pérez LM , Sánchez-Chávez E , et al. Digestibility, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of pecan nutshell (Carya illioinensis) extracts. J Renew Mater. 2022; 10: 2569– 80. doi:10.32604/jrm.2022.021163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Chandra S , Khan S , Avula B , Lata H , Yang MH , Elsohly MA , et al. Assessment of total phenolic and flavonoid content, antioxidant properties, and yield of aeroponically and conventionally grown leafy vegetables and fruit crops: a comparative study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014; 2014: 253875. doi:10.1155/2014/253875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Mishchenko O , Kyrychenko I , Gontova T , Kalko K , Hordiei K . Research on the phenolic profile, antiradical and anti-inflammatory activity of a thick hydroalcoholic feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium L.) herb extract. Sci Pharm Sci. 2022; 5( 39): 91– 9. doi:10.15587/2519-4852.2022.266400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Mykhailenko O , Korinek M , Ivanauskas L , Bezruk I , Myhal A , Petrikaitė V , et al. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of Ukrainian Iris species: a fresh look on their antioxidant content and biological activities. Molecules. 2020; 25( 19): 4588. doi:10.3390/molecules25194588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Apak R , Bener M , Çelik SE , Bekdeşer B , Şen FB . The CUPRAC method, its modifications and applications serving green chemistry. In: Green analytical chemistry. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2025. p. 357– 83. doi:10.1016/B978-0-443-16122-3.00007-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Amigo-Benavent M , Khalesi M , Thapa G , FitzGerald RJ . Methodologies for bioactivity assay: biochemical study. In: Biologically active peptides. Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press; 2021. p. 103– 53. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-821389-6.00030-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Korinek M , Tsai YH , El-Shazly M , Lai KH , Backlund A , Wu SF , et al. Anti-allergic hydroxy fatty acids from Typhonium blumei explored through ChemGPS-NP. Front Pharmacol. 2017; 8: 356. doi:10.3389/fphar.2017.00356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Böyum A . Isolation of mononuclear cells and granulocytes from human blood. Isolation of monuclear cells by one centrifugation, and of granulocytes by combining centrifugation and sedimentation at 1 g. Scand J Clin Lab Investig Suppl. 1968; 97: 77– 89. [Google Scholar]

32. Yang W , Pan Q , Li Q , Zhou S , Cao X . A simple, reliable and easily generalizable cell-based assay for screening potential drugs that inhibit lipid accumulation. Curr Res Toxicol. 2024; 8: 100213. doi:10.1016/j.crtox.2024.100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Chen YS , Chang HS , Hsiao HH , Chen YF , Kuo YP , Yen FL , et al. Identification of Beilschmiedia tsangii root extract as a liver cancer cell-normal keratinocyte dual-selective NRF2 regulator. Antioxidants. 2021; 10( 4): 544. doi:10.3390/antiox10040544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Feng SY , Jiang N , Yang JY , Yang LY , Du JC , Chen XQ , et al. Antiviral and anti-inflammatory activities of chemical constituents from twigs of Mosla chinensis Maxim. Nat Prod Bioprospect. 2024; 14( 1): 26. doi:10.1007/s13659-024-00448-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Le HY , Tang WF , Leu YL , Nguyen MH , Nguyen DT , Duyen Thi T , et al. Enterovirus D68: a novel inhibitor reveals underlying molecular mechanisms of viral entry and uncoating. J Med Virol. 2025; 97( 11): e70677. doi:10.1002/jmv.70677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Ochensberger S , Alperth F , Mitić B , Kunert O , Mayer S , Mourão MF , et al. Phenolic compounds of Iris adriatica and their antimycobacterial effects. Acta Pharm. 2019; 69( 4): 673– 81. doi:10.2478/acph-2019-0037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. de Villiers A , Venter P , Pasch H . Recent advances and trends in the liquid-chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis of flavonoids. J Chromatogr A. 2016; 1430: 16– 78. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2015.11.077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Li Y , Zhao Y , Tan X , Liu J , Zhi Y , Yi L , et al. Isoorientin inhibits inflammation in macrophages and endotoxemia mice by regulating glycogen synthase kinase 3β. Mediators Inflamm. 2020; 2020: 8704146. doi:10.1155/2020/8704146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Khatib S , Faraloni C , Bouissane L . Exploring the use of Iris species: antioxidant properties, phytochemistry, medicinal and industrial applications. Antioxidants. 2022; 11( 3): 526. doi:10.3390/antiox11030526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Kutova O , Sahaidak-Nikitiuk R , Kovalevska I , Demchenko N . Setting the equation of regression to determine the technological factors influence on the content of flavonoids in the extract. Sci Pharm Sci. 2022; 1( 35): 52– 7. doi:10.15587/2519-4852.2022.253547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Awad AM , Kumar P , Ismail-Fitry MR , Jusoh S , Ab Aziz MF , Sazili AQ . Green extraction of bioactive compounds from plant biomass and their application in meat as natural antioxidant. Antioxidants. 2021; 10( 9): 1465. doi:10.3390/antiox10091465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Mykhailenko O , Hsieh CF , El-Shazly M , Nikishin A , Kovalyov V , Shynkarenko P , et al. Anti-viral and anti-inflammatory isoflavonoids from Ukrainian Iris aphylla rhizomes: structure-activity relationship coupled with ChemGPS-NP analysis. Planta Med. 2023; 89( 11): 1063– 73. doi:10.1055/a-2063-5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Anju K , Gautam AS , Singh RK . Ferulic acid attenuated interleukin-17A-induced lung inflammation by modulating interleukin-17 signaling and tissue remodeling in a mouse model. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2025; 8( 10): 3641– 53. doi:10.1021/acsptsci.5c00490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Li H , Zhang H , Zhao H . Apigenin attenuates inflammatory response in allergic rhinitis mice by inhibiting the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway. Environ Toxicol. 2023; 38( 2): 253– 65. doi:10.1002/tox.23699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Park SH , Jeon YH , Park YJ , Kim KY , Kim JS , Lee JB . Guaijaverin and epigallocatechin gallate complex modulate Th1 and Th2 cytokine-mediated allergic responses through STAT1/T-bet and STAT6/GATA3 pathways. J Med Food. 2024; 27( 9): 844– 56. doi:10.1089/jmf.2023.k.0329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Jiang Y , Nguyen TV , Jin J , Yu ZN , Song CH , Chai OH . Tectorigenin inhibits oxidative stress by activating the Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway in Th2-mediated allergic asthmatic mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2024; 212: 207– 19. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2023.12.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Patergiannakis IS , Georgiou-Siafis SK , Papadopoulou LC , Pappas IS . Natural Nrf2 activators modulate antioxidant gene expression and apoptosis in leukemic K-562 cells. Med Oncol. 2025; 42( 9): 396. doi:10.1007/s12032-025-02946-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Dong T , Fan X , Zheng N , Yan K , Hou T , Peng L , et al. Activation of Nrf2 signalling pathway by tectoridin protects against ferroptosis in particulate matter-induced lung injury. Br J Pharmacol. 2023; 180( 19): 2532– 49. doi:10.1111/bph.16085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Lim JH , Park HS , Choi JK , Lee IS , Choi HJ . Isoorientin induces Nrf2 pathway-driven antioxidant response through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling. Arch Pharm Res. 2007; 30( 12): 1590– 8. doi:10.1007/BF02977329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Tang X , Liu J , Yao S , Zheng J , Gong X , Xiao B . Ferulic acid alleviates alveolar epithelial barrier dysfunction in sepsis-induced acute lung injury by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway and inhibiting ferroptosis. Pharm Biol. 2022; 60( 1): 2286– 94. doi:10.1080/13880209.2022.2147549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Lfitat A , Zejli H , Bousselham A , El Atki Y , Lyoussi B , Gourch A , et al. Comparative evaluation of Argania spinosa and Olea europaea leaf phenolic compounds and their antioxidant activity. Botanica. 2020; 26( 1): 76– 87. doi:10.2478/botlit-2020-0007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools