Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Mechanistic Insights into the Role of Melatonin in Cancer Cell Chemoresistance

1 Department of Cell Systems and Anatomy, UT Health San Antonio, Long School of Medicine, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA

2 Applied Biomedical Sciences, University of the Incarnate Word, School of Osteopathic Medicine, San Antonio, TX 78209, USA

3 Instituto de Medicina y Biologia Experimental de Cuyo (IMBECU), Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Cientificas y Tecnologicas (CONICET), Mendoza, 5500, Argentina

4 Department of Biomolecular Sciences, University of Urbino Carlo Bo, Urbino, 61029, Italy

5 Independent Researcher, Marble Falls, TX 78654, USA

6 Laboratory of Clinical Virology, School of Medicine, University of Crete, Heraklion, 71003, Greece

7 Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Complutense University of Madrid, Madrid, 28040, Spain

8 Department of Pathophysiology, Laiko General Hospital, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, 11527, Greece

9 SCI Research Institute, Jericho, New York, NY 11753, USA

* Corresponding Authors: Russel J. Reiter. Email: ; Ramaswamy Sharma. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Melatonin and Mitochondria: Exploring New Frontiers)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(11), 2033-2067. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.067661

Received 09 May 2025; Accepted 23 July 2025; Issue published 24 November 2025

Abstract

The development of cancer cell resistance to conventional treatments continues to be a major obstacle in the successful treatment of tumors of many types. The discovery of a highly efficient direct and indirect free radical scavenger, melatonin, in the mitochondrial matrix may be a factor in determining both the occurrence of cancer cell drug insensitivity as well as radioresistance. This relates to two of the known hallmarks of cancer, i.e., exaggerated free radical generation in the mitochondria and the development of Warburg type metabolism (glycolysis). The hypothesis elaborated in this report assumes that the high oxidative environment in the mitochondria contributes to a depression of local melatonin levels because of its overuse in neutralizing the massive amount of free radial produced. Moreover, Warburg type metabolism and chemoresistance are functionally linked and supplemental melatonin has been shown to reverse glycolysis and convert glucose processing to the type that occurs in normal cells. Since this metabolic type is a key factor in determining chemoresistance, melatonin would predictably also negate cancer drug insensitivity. The possible mechanisms by which melatonin may interfere either directly or indirectly with drug resistance are summarized in the current review.Keywords

Cells become more functionally pleiotropic when they transition into a cancer phenotype. Many cancer cells reorganize the glucose processing pathway such that the end product of glucose metabolism, pyruvate, is not transported into the mitochondria for conversion to acetyl coenzyme A [1]. Rather, pyruvate undergoes fermentation to lactic acid, which is released into the extracellular microenvironment where it acidifies the associated interstitial fluid [2]. This acidification aids in angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis of the cancerous cell [3]. This adopted metabolism of eukaryotic cells is referred to as Warburg metabolism, was discovered more than 100 years ago, and is sufficiently common that it is classified as a “Hallmark of Cancer” [4]. Although contributing to cancer cell chemoresistance, it is per se not the cause of the failure of cancer cells to respond to drugs that normally kill them. Processes such as immune escape also likely play critical roles.

Recent research has identified some of the molecular mechanisms driving this metabolic reprogramming. Key factors include hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) activation, oncogene-driven upregulation of glycolytic enzymes, and loss-of-function mutations in tumor suppressor genes [5,6]. These adaptations not only support rapid cellular proliferation but also contribute to chemoresistance by fostering a hostile tumor microenvironment and altering drug response pathways [7]. The elevated lactate levels characteristic of Warburg-metabolizing cells impair T-cell function and promote macrophage reprogramming, thereby exacerbating immune suppression/escape which typifies tumors [5].

Normal cells typically rely on mitochondrial respiration (oxidative phosphorylation; OXPHOS) for energy production (ATP) [8]; in contrast, cancer cells primarily derive energy from cytosolic glycolysis (Warburg metabolism). Cancer cells can switch their metabolic phenotype via tumor cell autonomous means or as a result of drug administration. Drugs that force cancer cells to adopt mitochondrial OXPHOS over cytosolic glycolysis for ATP synthesis are referred to as glycolytics; these drugs redirect glucose metabolism toward that of normal cells, thereby increasing the cancer cells’ sensitivity to conventional therapies such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy [9]. Some of the best-known glycolytic agents include synthetic chemicals, e.g., dichloroacetate and oxamic acid, and plant-derived flavonoids, e.g., quercetin, as well as plant non-flavonoid polyphenols, e.g., resveratrol [10,11].

The mechanisms by which melatonin may contribute toward inhibition of drug resistance are outlined in this review.

2 Cancer and the Intramitochondrial Oxidative Environment

Whether cancer cells live or die depends on the levels of highly reactive, damaging species that they produce or are unable to adequately detoxify. These reactive species are often referred to as free radicals or as reactive oxygen (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) [12]. A free radical, sometimes named simply a radical, is a molecule, an atom, or an ion that has one or more unpaired electrons in its valence orbital. Usually, these unbalanced electrons render the parent species highly reactive and damaging to neighboring molecules with the half-lives of the radical species being very short depending on their level of reactivity.

The mitochondrial electron transport chain (etc.,) is a major source of endogenous ROS (primary radicals) when an estimated 2%–4% of the electrons shunted between the complexes of the chain normally escape and chemically reduce nearby oxygen molecules to superoxide anion radical (O2∙−) (Fig. 1); additionally, NADPH oxidases (NOX) which are bound to membranes, cytosolic peroxisomes and members of the cytochrome P450 enzyme superfamily give rise to partially reduced oxygen species throughout the cell. Secondary oxygen-based lipid radicals are formed as damaged products of ROS and likewise must be incapacitated to forego extensive lipid peroxidation [13].

Figure 1: The generation of toxic derivatives of oxygen (free radicals or reactive oxygen species) occurs predominantly in mitochondria but also as a result of enzyme activities in other parts of the cell, represented here by NADPH oxidase and xanthine oxidase. As electrons are passed between the proteins of the electron transport chain (ETC) in the inner mitochondrial membrane, some are mishandled and interact with adjacent O2 molecules chemically reducing them to superoxide. Superoxide is quickly enzymatically dismutated by a family of enzymes referred to as superoxide dismutases (SOD), which are present in different isoforms and exist in mitochondria, cytosol, nucleus, and extracellular space, resulting in the formation of H2O2, a non-radical species that has a relatively long half-life and readily diffuses between cellular compartments and between cells. H2O2 can be removed by its metabolism to oxygen and water when it is acted upon by glutathione peroxidase (GPx) or catalase. However, H2O2 when contacted by a transition metal, represented here by iron or copper ions, transitions (the Haber-Weiss or Fenton reaction) into the short-lived and highly toxic ·OH which mutilates any molecule in the immediate vicinity of where it is produced; this is identified as on-site damage and includes dismantling of proteins (protein carbonyls), lipids (hydroperoxides) and DNA (DNA adducts). The superoxide radical can also form a complex with NO∙ to generate the oxidizing agent, ONOO– which is highly destructive. ONOO– nitrates both proteins and lipids as well as oxidizing DNA resulting in single strand breaks and initiating DNA repair processes. The damage it inflicts is often monitored by measuring cellular 3-nitrotyrosine levels. Melatonin and its metabolites directly detoxify each of the reactive molecules shown in this flow diagram, or they stimulate antioxidative enzymes which convert them to innocuous molecules. Because of the extremely short half-life of most of these toxic oxygen-based derivatives, but especially the ·OH, melatonin (or any radical scavenger) must be immediately adjacent to where it is formed if it is to neutralize it. Since a major portion of the radicals are formed because of electrons leaking from the ETC in the mitochondria, the presence of melatonin in this organelle may be a critical factor that accounts for its substantial antioxidant actions. GSSG = Glutathione disulfide (oxidized form); GSH = Glutathione (reduced form); GRd = Glutathione reductase

The O2∙– is rapidly converted by superoxide dismutase to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which is unstable, has a relatively long half-life (several seconds), readily diffuses through cellular membranes because it has no charge, and can accumulate in high concentrations relative to those of other oxidants. Additionally, the O2∙− reacts with nitric oxide (NO∙) to generate the non-radical but strongly oxidizing species, peroxynitrite (ONOO−) (Fig. 1). ONOO− causes damage to DNA and proteins and in doing so it disrupts many signaling pathways and contributes to cancer [14].

H2O2 is detoxified by its enzymatic conversion to O2 and H2O by both glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and catalase (Fig. 1). H2O2 is also transformed into the hydroxyl radical (·OH) via its metal-catalyzed decomposition during the Fenton reaction. Unlike its precursors, ·OH is not removed by enzymatic conversion and is only detoxified when being directly neutralized by a free radical scavenger, such as melatonin, vitamin C, glutathione, etc. It is believed to account for excess than 50% of the molecular damage that occurs in vivo, and it has been implicated as a contributor to many diseases. A commonly measured adduct of a ·OH and a DNA base is the 8-hydroxy-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) (Fig. 1).

The ·OH is the most rapidly reacting and destructive radical generated; its estimated half-life is in the range of 10−9 s. Thus, when generated, it mutilates any biomolecule (DNA, protein, or lipid) in the immediate vicinity of where it is formed; this is typically referred to as on-site damage. While usually thought of as creating molecular damage identified as oxidative (or nitrosative) stress, radicals sometimes also have critical functions in intermediary metabolism, or they may serve as signaling molecules, a process referred to as redox signaling [15].

3 ROS/RNS Detoxification in the Mitochondrial Matrix

Because of the short half-life of most ROS with their almost instantaneous interaction with adjacent molecules, if an ROS is to be neutralized before it can execute its damage, the detoxifying agent must be in the immediate neighborhood of where the ROS is produced. For example, given that mitochondrial respiration is a major contributor to ROS generation, molecules, i.e., antioxidants, that are located within the mitochondria may be of special importance in limiting free radical damage and thereby modulating the course of a disease [16].

To mitigate the mitochondrial damage potentially inflicted by ROS/RNS, cells have developed a complex system of antioxidants to protect biological molecules from oxidation. This system involves antioxidative enzymes that metabolize toxic agents to non-toxic species and a series of non-enzymatic small molecular weight direct radical scavengers [17,18]. In addition to the endogenously synthesized antioxidants (e.g., glutathione), others are attained via diet (e.g., vitamin C). Despite the ability of these substances to counter oxidative stress, some molecular damage slowly accumulates, which is believed to contribute to aging [19]. Oxidative stress is also an additional component of many diseases, including cancer [20–22]. As mentioned, ROS and RNS also serve as critical signaling molecules within cells; how or whether they escape being neutralized by antioxidants is not well defined. Clearly, ROS/RNS fulfill signaling functions before they are neutralized, suggesting a fine-tuned redox signaling system in mitochondria.

Melatonin is a powerful radical scavenger [23,24] that is synthesized in vivo and is also consumed in the diet, given its presence in all plants, edible and non-edible [25,26]. Melatonin was originally identified in the pineal gland where its synthesis is circadian and where its production is governed by the prevailing light: dark cycle. The cyclic release of melatonin from the pineal gland aids in the regulation of both systemic and cellular circadian rhythms [27]. A second non-releasable and non-circadian pool of melatonin exists, which has a totally different function [28,29]. Unlike pineal-derived melatonin which enters the circulation, the non-releasable pool of melatonin is synthesized in the mitochondria of presumably all somatic cells and aids in maintaining redox homeostasis; it accounts for an estimated 95% of the total melatonin produced in species that possess a pineal gland (vertebrates) and 100% of the melatonin synthesized in non-vertebrates (which lack a pineal gland) where it is involved in metabolic regulation and in redox homeostasis.

Controlling the intramitochondrial levels of H2O2 is especially critical for maintaining the redox balance since this non-radical product has essential roles in cell signaling as well as regulating the redox state [30,31]. Holding the concentrations of H2O2 and its signaling processes at low levels leads to eustress [32], i.e., an optimal level of oxidative activity which promotes cellular health. When H2O2 levels get too high, it leads to pathophysiological signaling and excessive ∙OH and HOCl (hypochlorous acid), which causes oxidative stress [32,33]. Clearly, careful control of optimal levels of H2O2 is critical in maintaining properly functioning molecular processes within cells.

H2O2 levels are a consequence of its production and its breakdown. It is normally formed by the enzymatic dismutation of O2∙− by superoxide dismutase (SOD), of which there are three isoforms. SOD is widely considered an important antioxidative enzyme [34], and it is normally upregulated by melatonin via sirtuin 3 (SIRT3). activation, at least in mitochondria [35]. The catabolism of H2O2 is primarily by glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and catalase (CAT), which, like SOD, are upregulated by melatonin. This is relevant to the theory that low levels of melatonin serve to initiate Warburg metabolism (glycolysis) [36]; the reduction in intramitochondrial melatonin concentrations during glycolysis may also relate to chemoresistance. During aerobic glycolysis, there is insufficient acetyl coA in the mitochondrial matrix to support high melatonin production (Fig. 2) resulting in a diminished level of this multifaceted antioxidant [37]. Since melatonin is also a direct scavenger of H2O2 [38], this combination of changes, i.e., reduction of H2O2 scavenging combined with down regulation of detoxifying antioxidative enzymes (SOD, GPx, and CAT) causes increased accumulation of H2O2 inducing the production of high levels of ONOO– and ∙OH. the two most destructive derivatives of otherwise healthy molecules. Thus, the reduction of mitochondrial melatonin in Warburg-metabolizing cancer cells helps to explain the high levels of free radicals in the mitochondria, a well-known hallmark of cancer cells.

Figure 2: This scheme illustrates how Warburg metabolism likely regulates the intramitochondrial levels of melatonin in cancer cells. The top figure shows that the metabolite of glucose, pyruvate, readily enters the mitochondria of normal cells where it is converted to acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl CoA) by the enzyme pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH). Acetyl CoA feeds the tricarboxylic acid cycle (not shown) and is also a substrate in melatonin synthesis. Acetyl CoA works in concert with serotonin (5-HT) to form N-acetylserotonin (NAS), the immediate precursor of melatonin; this action requires the enzyme aralkylamine N-acetyltransferase (AANAT). NAS is metabolized to melatonin with the aid of the enzyme, acetylserotonin methyltransferase (ASMT). Once generated, melatonin functions in the scavenging of reactive species (ROS and RNS) and stimulates antioxidative enzymes via upregulation of SIRT3. Since pyruvate readily enters normal cell mitochondria, ample acetyl CoA is available for melatonin synthesis thereby maintaining high cellular melatonin levels (histogram between images). During glycolysis (bottom image), which many cancer cells develop, pyruvate does not enter mitochondria due to inhibition of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) by the enzyme pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK), which is upregulated by hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α). This causes a reduction in acetyl CoA levels which in turn presumably leads to a depression in intramitochondrial melatonin concentrations (histogram between figures). The lower levels of melatonin in the mitochondria, a ubiquitous radical scavenger, aid the cancer cells in maintaining high free radical levels in these organelles, a hallmark of cancer cells. From Reiter et al. [39]; used with permission. LDH = lactic acid dehydrogenase; 5-HT = 5-Hydroxytryptamine; ASMT = N-acetylserotonin O-methyltransferase.

4 Melatonin Synthesis and Uptake by Mitochondria

Experimental evidence strongly supports the idea that the primary intracellular site of melatonin production is the mitochondria of all eukaryotic cells (animal and plant) [40,41], where its main function is presumably to combat oxidative/nitrosative stress. This prediction is consistent with the early evolution (3–2 billion years ago) of melatonin as an antioxidant in prokaryotic bacteria (Rhodospirillum rubrum) and in prokaryote archaea (Thermoplasma volcanium) [42–45]. Bacteria were subsequently phagocytized by eukaryotes where they developed a beneficial partnership with the host cell and evolved into mitochondria; in doing so these organelles retained the ability to synthesize melatonin [46,47]. This sequence of events is known as the endosymbiotic theory, which is widely accepted by evolutionary biologists. Present-day mitochondria still retain many features in common with those of their prokaryotic ancestors [48].

Metabolites of melatonin which are formed when it functions in neutralizing free radicals are likewise potent radical scavengers and also promoters of antioxidative enzymes, like melatonin itself [49–53] (Fig. 3). Unlike the direct radical scavenging actions of melatonin which are receptor independent [40,54], its actions on upregulating enzymes that remove ROS from the cellular environment are receptor mediated (Fig. 4) [17,21,50]. Melatonin protects lipids, proteins and DNA (Fig. 1) by inactivating processes that cause damage to these molecules as well as by activating DNA repair mechanisms [55,56]. Thus, melatonin has multiple means by which it keeps oxidative stress to a minimum and maintains redox homeostasis, especially in mitochondria.

Figure 3: Melatonin, a molecule that is produced endogenously in mitochondria and can be used as a supplement and is consumed in the diet, has a plethora of actions that make it a potent direct scavenging agent and indirect antioxidant. Listed in green are the radicals or associated toxic derivatives of oxygen or nitrogen which melatonin neutralizes by direct scavenging. Listed in red are the anti- and pro-oxidative enzymes modulated by melatonin that further increases its ability to reduce oxidative stress. In addition to the capacity of melatonin to carry out these actions, metabolites that are formed when it scavenges reactive radicals (e.g., cyclic 3-hydroxymelatonin, N-acetyl-N-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine, N-acetyl-5-methoxykynuramin, etc.) are also equal to or better than melatonin in doing so. The ability of melatonin as well as its metabolites to sequentially scavenge ROS/RNS is referred to as the antioxidant cascade and greatly increases the effectiveness of melatonin in alleviating oxidative stress. On the right are the physiological features of melatonin that contribute to its efficacy in limiting oxidative damage to all critical molecules; this list also includes melatonin’s other actions which make it an important and essential molecule in not only animals but in plants as well. Adapted from Reiter et al. (2016) [57] with permission

Figure 4: This figure summarizes the synthesis of melatonin from tryptophan (orange circles). In vertebrates, melatonin is produced in two distinctive sites, i.e., in the pineal gland and in the mitochondria of presumably all somatic cells. The function of melatonin from these two sources differs. Melatonin of pineal origin is synthesized and released from the pineal gland at night and serves to synchronize circadian rhythms. Melatonin generated in the mitochondria does not exhibit a day-night rhythm and is not released into the blood. Rather, it functions primarily in its cell of origin, where it participates in the maintenance of redox homeostasis. Illustrated in the green circles are the metabolites that are formed when melatonin directly scavenges ROS or RNS. Some of the resulting metabolites may be equal to or better than melatonin as radical scavengers. Melatonin is also enzymatically converted to agents (blue circles) that are scavengers. Moreover, melatonin functions as a signaling molecule to stimulate anti-oxidative enzymes (not shown). via these multiple actions, melatonin controls the oxidation state of the mitochondria and reduces oxidative damage to critical molecules in these organelles. TPH = tryptophan hydroxylase; AADC = amino acid decarboxylase; AANAT = aralkylamine N-acetyltransferase; HIOMT = hydroxyindole-O-methyltransferase; CYP450 = cytochrome P450; EPO = eosinophil peroxidase; HRP = horseradish peroxidase; IDO = indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; MPO = myeloperoxidase

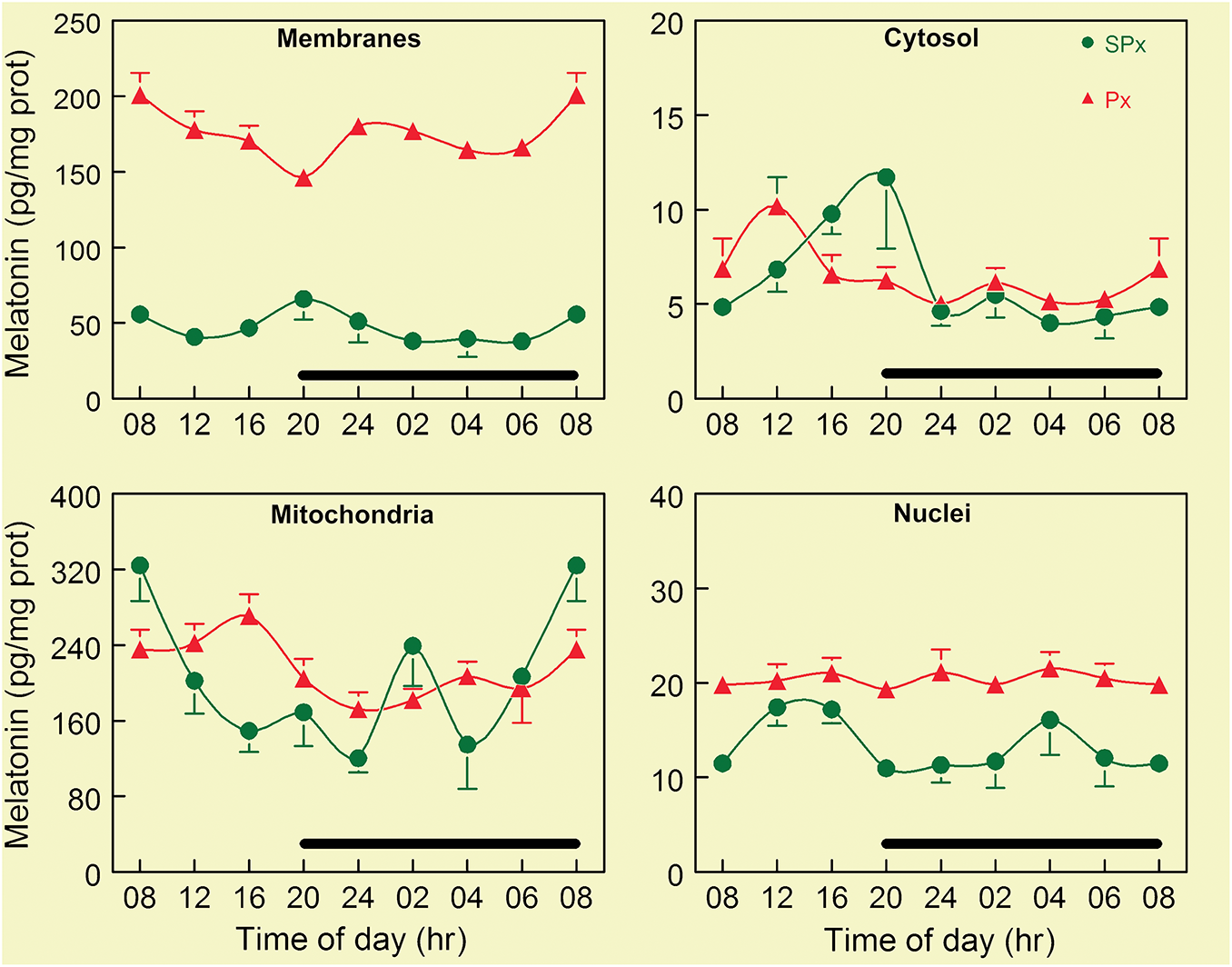

In a previous paragraph, it was pointed out that mitochondria are a major source of uninterrupted ROS production resulting from the leakage of electrons from the ETC which subsequently chemically reduce O2 to the O2∙− radical. To defend against this persistent onslaught of ROS, it is essential that the mitochondrial matrix be enriched with agents that can resist the hostile reactions initiated in the vicinity of the ETC. As indicated above, given the very short half-life of the most destructive of the toxic oxygen-based species (often in the nano- to femto- second range) [13], it is imperative that newly formed radicals are immediately neutralized by nearby antioxidants. The measured melatonin concentrations in purified hepatocyte and brain mitochondria reportedly far exceed that (by up to 10-fold) in the blood or in other portions of the cell, e.g., membrane fraction, cytosol, or nucleus (Fig. 5) [58]. Thus, its high concentration in the mitochondrial matrix allows melatonin to quickly quench radicals formed as a consequence of the escape of electrons from the ETC. Moreover, it is well documented that upregulated free radical generation in mitochondria of cultured neurons is quickly quenched by the application of exogenous melatonin to the growth medium [59], showing that intramitochondrial melatonin synthesis is supplemented by melatonin applied exogenously [60]. To date, studies related to the levels of melatonin in isolated mitochondria have used presumably normal cells [41,58]. Specifically in cancer cell mitochondria, no reported attempts have been made to measure the melatonin levels although cellular concentrations of melatonin in ovarian cancer cells are depressed relative to those in normal ovarian cells (Fig. 2). Since intracellular melatonin concentrations are highest in mitochondria, the intracellular levels of this antioxidant are likely to represent those in mitochondria (Fig. 5) [41,58].

Figure 5: This figure summarizes concentrations of melatonin over a 24-h period in four subcellular fractions of whole brain homogenates. Brains were collected from mice at regular intervals during both the day and the night. The cells were then fractionated into four subcellular components: membranes, cytosol, mitochondria, and nuclei. The basal concentration of melatonin (green dots) varied widely among the different components. Cytosol and nuclei had the lowest concentrations of melatonin, with values ranging from 5–20 pg/mg protein. Membranes had stable levels over the light: dark cycle at around 50 pg/mg protein. In comparison, mitochondria had by far the highest concentrations of basal melatonin, which range from 160 to 320 pg/mg protein. A high concentration of melatonin in these organelles was presumed to be a consequence of its intrinsic synthesis. To confirm that the melatonin in these organelles was not a result of the uptake of pineal-derived melatonin in the blood, melatonin measurements were also made in each subcellular component from brains collected from mice that had been pinealectomized (Px) three weeks before tissue collections. The reduction in blood melatonin levels due to pinealectomy clearly did not depress the melatonin concentrations in any subcellular component. Rather, nuclear concentrations were slightly increased, but the largest change occurred in the membranes where mean melatonin levels rose to four-fold the values measured in the sham-pinealectomized (SPx) mice. The reason for this large increase does not yet have an explanation. While there were no circadian changes in melatonin levels in any subcellular component, as in the pineal gland, there were short-term fluctuations. These were presumed to be a consequence of time-dependent differential synthesis and utilization as melatonin as a radical scavenger. The black bar in each of the panels indicates the period of darkness. Figure adapted from Venegas et al. [58] and published with permission

The evidence that melatonin is synthesized directly in mitochondria is highly compelling, and moreover it may be inducible in these organelles in all species. Its inducibility under abiotic and biotic stressful conditions is commonplace in plant cells [61], and this may also apply to vertebrate cells at extrapineal sites [62]. Melatonin can also enter these organelles from the circulation [60]. The rise in nighttime blood levels is a result of its secretion by the pineal gland [63]. Also, some melatonin enters the blood and cells after its consumption in the diet since melatonin is widespread in both edible and non-edible plants [64]. Its transport into the cell and into mitochondria is likely a result of simple diffusion because of its amphiphilic nature, via glucose transporters [65] and through the oligopeptide-driven transporters, 1 and 2, which are present in both cellular and mitochondrial membranes [66]. The receptor mediated actions involve MT1 and MT2 receptors on the cell membrane [67] and possibly by means of lesser known cytosolic binding sites (quinone reductase II enzyme (MT3), calmodulin, etc.) [68] and via nuclear receptors related to the superfamily of orphan receptors, although this has been frequently under debate [69]. The MT1 receptor has also been identified on the mitochondrial membrane and is reportedly involved in autocrine mitochondrial feedback processes influencing cytochrome c release by melatonin discharged from mitochondria in the same cell [41,70].

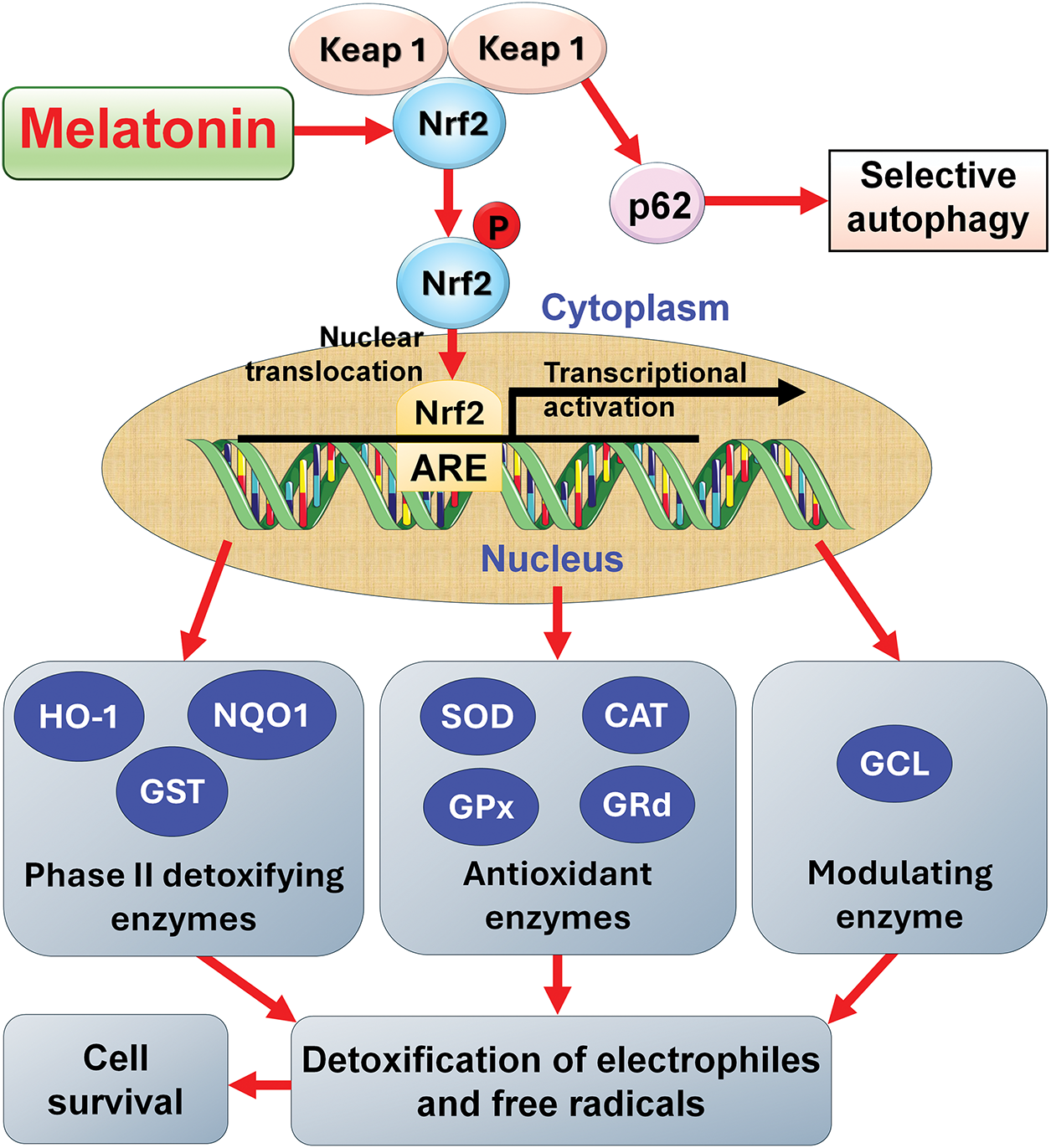

The levels of the well-known classical antioxidants generally have not been well defined as to their concentrations in individual organelles. For example, much of the data on the cellular distribution of vitamins C and E comes from plant studies since that is where they are produced [71]. When exogenously administered to animals, water soluble vitamin C does aid in preserving mitochondrial physiology in cells when their function is compromised due to toxin exposure [72]. Fat soluble vitamin E has eight natural isoforms and protects against the oxidation of polyunsaturated fats (PUFA), including those in the mitochondrial membranes [73]. The tripeptide glutathione is located in the mitochondrial matrix where it serves as a redox buffer (Fig. 1) [74]; glutathione synthesis is under the influence of melatonin [75,76]. The enhanced levels of glutathione in melatonin treated cells is a consequence of melatonin’s action on nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (Nrf2), an important transcription factor which upregulates not only glutathione but antioxidative enzymes as well (Fig. 6). Melatonin has been specifically identified as a mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant [77–79] and it has multiple actions by which it diminishes oxidative stress [57]. To date, no direct studies have been performed to compare melatonin’s ability to reduce oxidative stress in mitochondria relative to that of other antioxidants. Also, there are circumstances where melatonin may synergize with diet-derived antioxidants to limit ROS-mediated molecular damage [80], although no experiments have examined these associations in mitochondria. Future direct comparisons of melatonin with other mitochondrial antioxidants will be critical to fully elucidate its relative and potentially synergistic roles in redox regulation.

Figure 6: The ability of melatonin to promote glutathione synthesis and stimulate key antioxidative enzymes, as well as phase two detoxifying enzymes is a result of melatonin’s ability to stabilize the transcription factor Nrf2 as illustrated in this figure. Nrf2 is prone to undergo selective autophagy after it dissociates from Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1). By stabilizing Nrf2, melatonin allows it to escape degradation so its translocation into the nucleus is ensured where it interacts with the antioxidant response element (ARE) to induce the transcription of the genes of all of the enzymes indicated. Collectively, these enzymes control oxidative damage by reducing the negative impact of free radicals on cellular molecules. These actions ensure the health of a cell and promote its survival. CAT = catalase; GCL = glutamine cysteine ligase; GPx = glutathione peroxidase; GRd = glutathione reductase; GST = glutathione S-transferase; HO-1 = heme oxygenase-1; NQO1 = NADP(H) quinone dehydrogenase 1; p62 = Sequestome 1; SOD = superoxide dismutase

5 Melatonin and Cancer Drug Chemoresistance: Mechanisms

5.1 Warburg-Type Metabolism and Its Association with Chemoresistance

The upregulation of aerobic glycolysis (Warburg metabolism), which is accompanied by chemoresistance, in cancer cells is potentially induced by any of several intrinsic or extrinsic processes which are believed to have a common physiological basis [1]. Hence, we recently proposed that glycolysis is initiated when intramitochondrial melatonin levels drop to an undefined low level [36]. Normally, melatonin concentrations in mitochondria are governed by the transport of pyruvate into the mitochondria where it is converted by the enzyme, pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDH), to acetyl co-enzyme A (acetyl CoA) [29,39]. In addition to being important for the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) and OXPHOS, acetyl CoA is a required co-factor for serotonin to be converted to N-acetylserotonin, the immediate precursor of melatonin. The lack of adequate amounts of acetyl CoA likely limits the synthesis of intramitochondrial melatonin, as suggested by the findings of Gaiotte and colleagues [81] as well as by Cucielo and colleagues [82], who measured reduced melatonin concentration in ovarian cancer cells although not specifically in the mitochondria. While fatty acid β-oxidation (FAO) is an alternate source of acetyl CoA synthesis [83], with reduced melatonin levels, this pathway is likewise depressed [84–86].

5.2 Mitochondrial Oxidative Environment and Chemoresistance

In addition to Warburg metabolism, another feature of cancer cells is a sustained high oxidative environment in the mitochondria (Fig. 1). This oxidatively hostile microenvironment develops when electrons leak from complexes I and II of the ETC, leading to the chemical reduction of O2 and the generation of excessive ROS. The elevated ROS serve as essential signaling molecules providing optimal metabolic homeostasis for the growth and proliferation of the cancer cells. Even though melatonin, which exists in the mitochondrial matrix, is an efficient radical scavenger, its reduced level resulting from the depressed levels of acetyl CoA, is predictably overwhelmed by the massive onslaught of ROS in cancer cell mitochondria to the point where it becomes increasingly more deficient such that it is no longer at adequate concentrations to detoxify the large amounts of ROS (Fig. 2). Since high levels of melatonin in mitochondria are required to enhance the activity of the rate limiting enzyme in acetyl CoA synthesis, PDH, while also inhibiting HIF1α which disinhibits PDH, melatonin’s reduction leads to a massive downregulation of PDH which lowers the synthesis of the necessary co-factor, acetyl CoA, causing a further decline in intramitochondrial melatonin levels and initiation of glycolysis [29,87,88] and chemoresistance. This hypothesis is strengthened by the observations that supplementing cancer-bearing animals with parenterally administered melatonin elevates intramitochondrial melatonin levels [60] and concurrently reverses the Warburg effect, restores OXPHOS and likely reduces chemoresistance.

5.3 Mitochondrial Function and Pyruvate Processing: Relation to Chemoresistance

The uptake of endogenously produced or exogenously administered melatonin by mitochondria has a direct effect on the means by which many cancer cells process pyruvate. SKOV-3 and CAISMOV-24 ovarian cancer cells self-regulate their means of energy metabolism to support the rapid growth and progression of the tumor [89]. This involves pyruvate fermentation in the cytosol in lieu of its transport into the mitochondria and its conversion to acetyl CoA, i.e., they use glycolysis rather than OXPHOS as their main energy source. Treatment of the ovarian cancer cells with melatonin suppressed the expression of HIF-1α, PDK, and the activities of several enzymes involved in glucose breakdown and also upregulated PDH even when the cells were treated with luzindole, which blocks the major melatonin receptors, MT1 and MT2. Also, lactate levels were diminished, as were glutamine levels, because of melatonin treatment. Clearly, melatonin had rewired cellular metabolism from glycolysis to mitochondrial OXPHOS and, in doing so, it deprived the cancer cells of the preferred metabolic phenotype essential for accelerated growth and cellular proliferation [89]. Moreover, the increased mitochondrial melatonin concentrations are presumably related to reduced chemoresistance as mentioned above.

The findings of Silveira and colleagues [89] are in line with the known actions of melatonin in cancer cells that are experiencing glycolysis. Melatonin is a frequently documented inhibitor of HIF-1α, which in turn down regulates PDK, leading to the disinhibition of PDH [90]. This allows pyruvate to enter the mitochondria with its conversion to acetyl CoA which supports intramitochondrial melatonin synthesis [88,91] and contributes to its anti-cancer effects and to the reversal of chemoresistance.

5.4 Melatonin Rewires Glucose Metabolism: Relation to Chemoresistance

Historically, melatonin was thought to reprogram energy metabolism from cytosolic glycolysis to OXPHOS only in pathological (cancer) cells. However, Jauhari recently demonstrated the ability of melatonin to also metabolically reprogram non-cancerous differentiated mature neurons to OXPHOS, which they require to maintain their viability [92]. This report documented that treating arylalkylamine-N-acetyltransferase-knock out (AANAT-KO) neurons with exogenous melatonin induced them to be transformed from glycolysis-dependent cells to relying on OXPHOS as their primary energy source. Hence, a deficiency of mitochondrial melatonin prior to the neurons being supplemented with this molecule, led the cells to employ glycolysis in lieu of OXPHOS for their major source of ATP. This is consistent with low intramitochondrial melatonin levels resulting from a deficiency in acetyl CoA (a co-substrate with serotonin for NAS synthesis), being the basis of failed metabolic reprogramming [36]. Thus, the intramitochondrial levels of melatonin seem to be a major factor in determining the metabolic phenotype of both pathological and normal cells.

As already noted, one hallmark of cancer is the generation of what seems to be an excessive number of free radicals [93]. While this is likely valid, the depressed levels of melatonin in Warburg metabolizing cells probably also contribute to the higher concentrations of ROS. Melatonin and its metabolites are highly efficient free radical scavengers, and they also metabolically remove reactive species by stimulating antioxidative enzymes, e.g., MnSOD, GPx, etc. (Fig. 3) [48,57,94]. The absence of these processes due to a melatonin deficiency may cause a relative rise in ROS levels even above that due to their increased generation [36].

When melatonin rewires glucose metabolism in cancer cells, it also often may reverse their resistance to conventional anti-cancer medications and to radiotherapy. Many cancer types, but not all, become refractory to drug and radiation therapy, and it is often accompanied by Warburg type metabolism and the redox environment of the mitochondrial matrix. While Warburg metabolism may be a factor in the resistance of cancer cells to drugs, there are also other metabolic features and alterations in the tumor microenvironment that participate in chemoresistance development. There has been extensive research attempting to define the molecular mechanisms that account for cancer resistance to drugs or radiation treatment but there is no universal consensus on what cellular processes change would explain this phenomenon [95–97]. Clearly, new strategies are necessary to combat cancer drug resistance.

Since glycolysis is potentially related to depressed intrinsic melatonin levels and this metabolic phenotype typically partners with chemoresistance, here we propose that chemoresistance (and radioresistance) of cancer to treatment may also involve lower than normal intramitochondrial melatonin concentrations. The microenvironment of cancer cell mitochondria is characterized by a highly oxidizing state due to the excessive formation of ROS, perturbations of GSH production, GSH/GSSG ratio in favor of GSSG, and diminished melatonin levels. Additionally, factors such as upregulated HIF1α, downregulated PDH, faulty DNA repair, hyperactive phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-protein kinase B (AKT)-mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, loss of SIRT3, and alterations in profiles of microRNAs further exacerbate mitochondrial dysfunction [98,99]. The implication is that if these deficiencies were corrected and healthy mitochondria could be re-established, perhaps chemo- and radio-resistance could be counteracted.

5.5 PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling and Chemoresistance

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR (PAM) signaling pathway is a well conserved network that is found in all eukaryotic cells. A major function of this transduction network is to support cell survival, advance cellular growth, and aid in the progression of the cell cycle [100,101]. Disruption of the PAM signaling pathway has a major effect in terms of driving cancer growth and progression [102,103] and is the most frequently hyperactivated signaling pathway in cancer [104,105]. Relevant to the current discussion, PAM activation has also been implicated in rendering cancer cells chemoresistant [106–108].

Melatonin has been investigated relative to the dysregulated PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in several solid tumors [109]. In MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, melatonin inhibited the phosphorylation of AKT and mTOR, which caused the reduction in a number of survival proteins, including cyclin D1, cyclin E, and Bcl-XL [110]. In gallbladder cancer cells, melatonin also repressed the PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis and inhibited cellular proliferation and migration [111]. Tyrosine receptor kinase B is an important mediator in the activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, and available data indicates it is inhibited by melatonin in glioblastoma cells [112]. In human KGN (granulosa-type tumor) cells as well, melatonin downregulated the PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis, which was associated with an enhancement of autophagy [113]. While the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway has been implicated in determining chemoresistance [98], whether melatonin modulates this pathway to impact chemoresistance has not been specifically investigated, but this would seem to be highly likely. In numerous reports, the activity of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway has been shown to be influenced by the intracellular redox environment [114–116], with melatonin serving a primary role in the regulation of oxidative stress.

Emerging evidence suggests that melatonin negatively regulates the hyperactivated PAM pathway in various cancer models, leading to decreased expression of survival proteins and enhanced pro-death pathways such as autophagy. Mechanically, whether the suppression of the PAM pathway by melatonin is direct or indirect has not been resolved. Melatonin is a highly effective direct radical scavenger as well as an indirect antioxidant. It is presumed that one or both of these actions account for its ability to inhibit the PAM pathway. Thus, this action of melatonin could be receptor-independent and/or receptor-mediated. Given the pivotal role of PAM hyperactivation in driving chemoresistance and considering melatonin’s redox-regulatory functions that further influence PAM activity, it is highly plausible that melatonin supplementation could sensitize cancer cells to chemotherapeutic agents by dampening PAM signaling. This connection, while not yet directly explored in chemoresistance contexts, represents a promising avenue for future investigation.

5.6 Thymidylate Synthase, microRNAs, and Chemoresistance

Thymidylate synthase (TYMS) functions in cellular replication, transcription regulation, and DNA repair and is involved in the synthesis of the nucleic acid thymine. TYMS inhibition results in cellular deoxynucleotide imbalances, which may be relevant to cancer inhibition. Elevated expression of TYMS is considered a driver of cancer chemoresistance [117,118]. Melatonin was recently found to downregulate the protein expression of TYMS in colon cancer cells resistant to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), a conventional drug for this cancer type, not dissimilar to the action of miRNAs that can enhance chemosensitivity to 5-FU by negatively regulating TYMS expression [119]. In the report in question, melatonin inhibited TYMS and increased the inhibitory response of the cancer cells to 5-FU, which involved the overexpression of miR-215-5p [120]. The authors concluded that the exaggerated expression of miR-215-5p is a critical step by which melatonin suppressed TYMS expression. While the findings clearly show the inhibitory effects of melatonin occurred in presumably chemoresistant cancer cells, it is possible that melatonin initially reversed chemoresistance and thereafter also enhanced the suppressive action of 5-FU. The results also indicate that the microRNA, miR-215-5p, may be involved in the mechanism by which melatonin reduces chemoresistance. If, in fact, melatonin reversed chemoresistance in this study (this was not examined), it would likely have involved an elevation of intramitochondrial melatonin levels followed by redirecting glucose processing by the cancer cells from aerobic glycolysis to OXPHOS [36]. This should be further examined along with the role of melatonin in regulating the expression of microRNAs specifically in cancer cells in relation to chemoresistance. Of special importance may be the p53/miR-149-3p/PDK2 pathway, which alters the means by which glucose is processed in cancer cells [121]. Redirecting pyruvate, the glucose metabolite, into the mitochondria is associated with an interruption of Warburg type metabolism and potentially also of chemoresistance [36].

Another small non-coding RNA, miRNA-21, has a significant role in influencing gene expression in cancer cells, where it is usually overexpressed; thus, it is considered a biomarker in the diagnosis of cancer. This miRNA is involved in a variety of cancers and other diseases [122]. The regulation of miRNA-21 by melatonin may be a major epigenetic means by which melatonin influences tumor growth and metabolism. At the current level of understanding, however, there is no definitive evidence that the modulation of miRNA-21 (or of other miRNAs in this group, i.e., -20a or -27a) by melatonin relates to perturbations in cancer chemoresistance [123].

Melatonin has emerged as a promising epigenetic regulator in cancer therapy, particularly through its modulation of DNA methylation. A recent review summarized evidence from various models showing that melatonin influences DNA methylation by regulating the activity of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), especially DNMT1, thereby reactivating silenced tumor suppressor genes and repressing oncogenes. Genome-wide methylation profiling of the breast cancer cell line, MCF-7, demonstrated that melatonin exposure led to downregulation of oncogenic genes such as POU4F2 and upregulation of tumor suppressors like Glypican-3 (GPC3). In glioblastoma stem cells, melatonin enhanced sensitivity to temozolomide by inducing methylation and silencing of the ABCG2/BCRP gene, which encodes a key multidrug resistance transporter. Moreover, melatonin reduced inflammation-driven DNA demethylation in colon cancer models, while studies in mice exposed to artificial light at night showed that melatonin supplementation restored global DNA methylation levels and reduced tumor growth and metastasis. Collectively, these findings underscore melatonin’s potential as an adjuvant therapy to overcome chemoresistance and epigenetic dysregulation in cancer [124].

Melatonin also reversed multidrug resistance (MDR) in oral cancer through epigenetic and signaling modulation [125]. This group investigated vincristine (VCR)-resistant oral squamous cell carcinoma cell lines and found that melatonin significantly reduced cell viability and colony formation, while inducing apoptosis and autophagy. Mechanistically, melatonin upregulated the expression of two microRNAs, miR-34b-5p and miR-892a, known to target and suppress the MDR-associated genes ABCB1 and ABCB4, both of which encode drug efflux transporters that contribute to chemoresistance. Inhibiting these miRNAs reversed melatonin’s apoptotic effects, confirming their functional role.

In this study, melatonin’s impact on apoptosis was associated with activation of caspase-3, caspase-9, and PARP cleavage, while autophagy was indicated by increased LC3-II, SQSTM1, and beclin-1. The effects were regulated via modulation of key signaling pathways, including inhibition of AKT and p38, and activation of JNK. In vivo, melatonin reduced tumor growth and downregulated ABCB1/ABCB4 expression in a xenograft model, reinforcing its therapeutic potential. These findings underscore melatonin’s capacity to resensitize resistant oral cancer cells to chemotherapy by targeting both microRNA-mediated and signaling mechanisms of drug resistance [125].

Suppression of the circadian melatonin signal, particularly due to light exposure at night (LAN), induces intrinsic resistance to paclitaxel (PTX) in breast cancer. Xiang and colleagues observed that rats bearing breast cancer xenografts exposed to LAN exhibited accelerated tumor growth with complete insensitivity to PTX, whereas those supplemented with melatonin showed significant tumor regression [126]. Mechanistically, LAN exposure, which causes melatonin suppression, led to activation of the oncogenic STAT3 pathway through both phosphorylation and acetylation at lysine 685, which in turn up-regulated DNMT1. DNMT1 silenced the tumor suppressor gene ARHI (also known as DIRAS3) by promoter methylation. Loss of ARHI removed its inhibitory effect on STAT3, perpetuating the resistant phenotype. Melatonin reversed this process by inducing SIRT1, a deacetylase that suppresses STAT3 acetylation, downregulates DNMT1, and demethylates the ARHI promoter, thereby restoring ARHI expression and paclitaxel sensitivity. Clinically, analysis of breast tumor samples from the I-SPY 1 trial revealed that high expression of the MT1 melatonin receptor was significantly associated with a complete pathological response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy [126].

The puzzling, opposing effects observed, where melatonin reportedly inhibits and promotes the expression of miRNA-21 [123], may reflect its proposed ability to regulate phase separation activities associated with N-6-methyladenosine (m6A) modifications that control the expression and biological activities of miRNAs [127–130]. The overexpression of miRNA-21 can exert oncogenic functions by suppressing PTEN and activating PI3K/Akt signaling to inhibit autophagy and escape apoptosis [131,132]. Interestingly, the delivery of miRNA-21 into mitochondria that elevates ATP synthesis and reduces ROS production, potentially aiding cancer cell evasion of apoptosis, is enabled by nanoparticles formed via miRNA phase separation [133]. Furthermore, it is believed that ATP regulates the compartmentalization of membraneless biomolecular condensates (BCs) in a biphasic manner. By augmenting the proposed adenosine moiety effect of ATP, melatonin can readily exert biphasic, opposite effects on miRNAs via the regulation of phase separation [134,135]. Phase separation-mediated BCs are increasingly associated with tumor pathogenesis and chemoresistance [136–138]. Further studies investigating the relationship between melatonin regulation of BC phase separation and chemoresistance may be warranted.

5.7 Cancer Stem Cells and Their Potential Association with Chemoresistance

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are a subpopulation within tumors implicated in initiation, metastasis, and resistance to conventional therapies, largely due to their self-renewal capabilities, expression of stemness markers, and high drug efflux capacity. Melatonin was shown to target the CSCs by reducing their viability and downregulating key resistance mechanisms. A recent study by Cataldo and colleagues [139] investigated the effect of melatonin on CSC-like spheres derived from canine mammary carcinoma cells (CF41.Mg and REM134 lines). They observed that melatonin significantly decreased the viability of CF41.Mg spheres at both 48 and 72 h, though this effect was not observed in REM134 spheres, indicating a cell line–specific sensitivity.

Importantly, melatonin treatment resulted in a marked downregulation of the multidrug resistance genes MDR1 (ABCB1) and ABCG2, which encode drug efflux transporters associated with chemo-resistance. These effects occurred independently of the melatonin MT1 receptor, as blocking MT1 with luzindole did not reverse melatonin’s action. This indicates that the changes induced by melatonin may have involved its direct radical scavenging actions. Melatonin’s capacity to reduce MDR gene expression underscores its potential as a modulator of drug resistance phenotypes in CSCs and supports further exploration in long-term or higher-dose studies. These findings suggest that melatonin may selectively impair CSC viability and suppress key molecular drivers of chemoresistance [139].

The microenvironments in which these specialized cells exist, identified as CSC niches, help them to maintain their stemness and also facilitate immune evasion [140,141]. The stem cell niches allow for avoidance of immune surveillance using several strategies, one of which is the promotion of immune check point proteins. A major check point protein operative in this scheme is programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) [141]; this agent brings about an immunosuppressive microenvironment by reducing T-cell activation [142].

Melatonin was recently shown to suppress PD-L1 expression in two hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells (Huh7 and HepG2) and in a mouse model of HCC. The inhibition of PD-L1 was accompanied by a reduction of tumor growth and reversal of immune escape [143]. The mechanism by which melatonin suppressed PD-L1 expression involved its well-known ability to downregulate HIF-1α and the activation of the MAPK-JNK and MAPK-p38 pathways. It is unlikely, at least in the in vitro studies, that the actions of melatonin involved CSCs. A literature search failed to identify any publications where melatonin was specifically investigated relative to its interactions with PD-L1 in CSCs.

5.8 Anastasis, Ferroptosis and Chemoresistance

Recently, the interactions of cellular anastasis and ferroptosis and their interplay with ROS have been proposed to be of potential value in combating chemoresistance [144]. Each of these processes involves perturbations in mitochondrial physiology. The strategic location of melatonin in these organelles associated with its ability to scavenge ROS, enhance anastasis and alter ferroptosis indicates that, via these combined actions, melatonin could impact cancer drug resistance [145,146]. Currently, however, there are no experimental investigations of these suppositions. Combining melatonin with ferroptosis inducers or anastasis inhibitors might reveal synergistic or antagonistic effects on chemoresistance.

5.9 Tumor Microenvironment and Chemoresistance

The ability of cancer cells to resist inhibition by chemotherapies is impacted by the composition of the tumor microenvironment (TME) where cancer cells are directly exposed to a variety of stromal elements including immunocompetent cells and fibroblasts, tumor associated macrophages, pericytes, etc., all of which may promote drug resistance [147]. The mechanisms of modulation include perturbations in drug delivery resulting from alterations in the makeup of the extracellular matrix (ECM) along with the stimulation of cellular survival pathways. Many of the interactions of stromal cells with cancer tissues involve both direct and indirect signaling. Direct communication may include cell adhesion, gap junctions, extracellular vesicles (EV), tunneling nanotubes (TNT), etc., which transmit autocrine and intracrine messaging [148,149]. Also, cells in the ECM indirectly communicate via paracrine, endocrine or synaptic signaling. These interactions induce alterations in adjacent cells by changing gene expression, altering the cytoskeleton, and promoting the secretion of specific molecules from the recipient cells [150].

A number of reports have confirmed that melatonin both indirectly and directly determines the composition of the cancer cell microenvironment and induces changes that may impact the response of the cells to chemotherapies [151]. Since melatonin reconfigures Warburg metabolism back to OXPHOS, lactic acid release by the cancer cells is depressed, thereby reducing the acidity of the microenvironment. Melatonin also changes the activities of the intrinsic cell types that are present in the ECM. The results of these changes in reference to cancer cell responsiveness to what are normally inhibitory drugs are ill-defined with the emphasis of this work being directed to the microenvironment and its effects on cellular invasion and metastasis [150,152].

Cancer cells also develop chemoresistance when the cells engage processes that allow them to avoid immune surveillance, an adjustment referred to as immune escape [153]. The phenomenon of immune escape is only one aspect of chemoresistance, and they are invariably interconnected. The immunomodulatory actions of melatonin foreshadow its potential involvement in involving the processes that determine immune escape [154]. In experimental hepatocarcinoma (HCC), immune escape involves the increased expression of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) on the surface of the cancer cells [143]. This ligand then binds to programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) protein on the intrinsic immune cells suppressing the ability of the immune elements to kill the cancer cells, i.e., enhancing immune escape. In both cultured HCC cells and in in vivo HCC models, melatonin inhibited tumor growth and repressed the expression of PD-L1 and elevated T lymphocyte levels in the spleen of the experimental animals thereby augmenting the inhibitory action (above the direct tumor suppressive effect) of melatonin on tumor growth and avoiding tumor escape/chemoresistance. The authors identified the potential mechanisms by which melatonin impaired PD-L1 upregulation as involving reduced expression of the upstream transcription factor, HIF-1α, and the possible participation of the MAPK-P38 and/or the MAPK-JNK pathways [143]. Melatonin is a known inhibitor of HIF-1α expression [36]. These changes were initiated by the actions of melatonin in the cellular microenvironment.

Using colorectal cancer (CRC) cells, Li and co-workers reported that the combination of hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) exposure, which alters the state of the otherwise hypoxic microenvironment, and melatonin highly effectively inhibited cancer cell survival, which involved multiple mechanisms [155]. The loss of sensitivity of cancer cells to drugs normally used to control their growth continues to present a major obstacle for clinical oncologists. Thus, the importance of defining the mechanisms that initiate chemoresistance and identifying drugs that reverse the process cannot be overstated. Chemoresistance is, however, associated with a multitude of cellular and mitochondrial changes, making it difficult to decipher which of the processes proposed is most relevant to drug resistance. Some of the multitude processes that are associated with drug resistance are presented in narrative form in previous sections of this report. Adding further complexity, chemoresistance is not solely an acquired phenomenon but can also emerge intrinsically due to inherent genetic and epigenetic heterogeneity within tumors. Moreover, there seem to be many overlapping mechanisms involved with either the onset and/or continuance of cancer cell chemoresistance. In the absence of definitive knowledge of the mechanisms involved, the fabrication of drugs to combat this process cannot advance. Without a clear understanding of the dominant pathways and their interactions, the development of rational and targeted interventions remains severely impeded.

5.10 Chronic Inflammation and Cancer Chemoresistance

Chronic inflammatory processes play a significant role in allowing cancer cells to become unresponsive to chemotoxic drugs and also facilitate tumor aggressiveness and progression [156]. In contrast, acute inflammation often induces immune activation which leads to inhibition of tumor cell proliferation. In the majority of cases, however, the inflammatory response advances to a chronic state during which the tumor microenvironment becomes immunosuppressive due to the activation of regulatory T cells (Treg cells), polarization of macrophages to the inflammatory M1 phenotype, and stimulation of myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSC), dentritic cells (DC), cancer associated fibroblasts (CAF) and others. This combination of immunosuppressive cells produces growth factors, chemokines and cytokines which support tumor immune escape, leading to accelerated growth and drug resistance [157]; additionally, suppressor genes such as p53 and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) contribute to immune escape. The upregulation of PI3K, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), and mTOR also render tumor cells increasingly resistant to cancer drug therapies [158,159]. Moreover, chronic inflammation provides a highly suitable environment for new blood vessel protrusion into the growing tumor which aids in the development and maintenance of mutations in addition to enhancing invasion into surrounding tissue and metastasis [160]. A host of extrinsic and intrinsic factors can trigger the chronic inflammatory response, e.g., poor diet, use of tobacco products, psychological stress and many others; their influence in relation to a specific cancer can vary by tumor type but in every case an excess of ROS is generated [161].

Due to its capability of inducing chronic inflammation, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) has a role in cancer chemoresistance [162]. This transcription factor influences the expression of genes that upregulate inflammation which contributes to chemoresistance [156]. Interestingly, many chemotherapies which are used as cancer treatments eventually enhance chemoresistance due to their activation of NF-κB [163]. Likewise, dysregulated NF-κB stimulates the expression of anti-apoptotic genes thereby allowing cancer cells to evade the killing actions of the chemotherapeutic agents [164]. Cancer biologists consider that harnessing the NF-κB signaling pathways may be a beneficial means to diminish inflammation and limit chemoresistance [165].

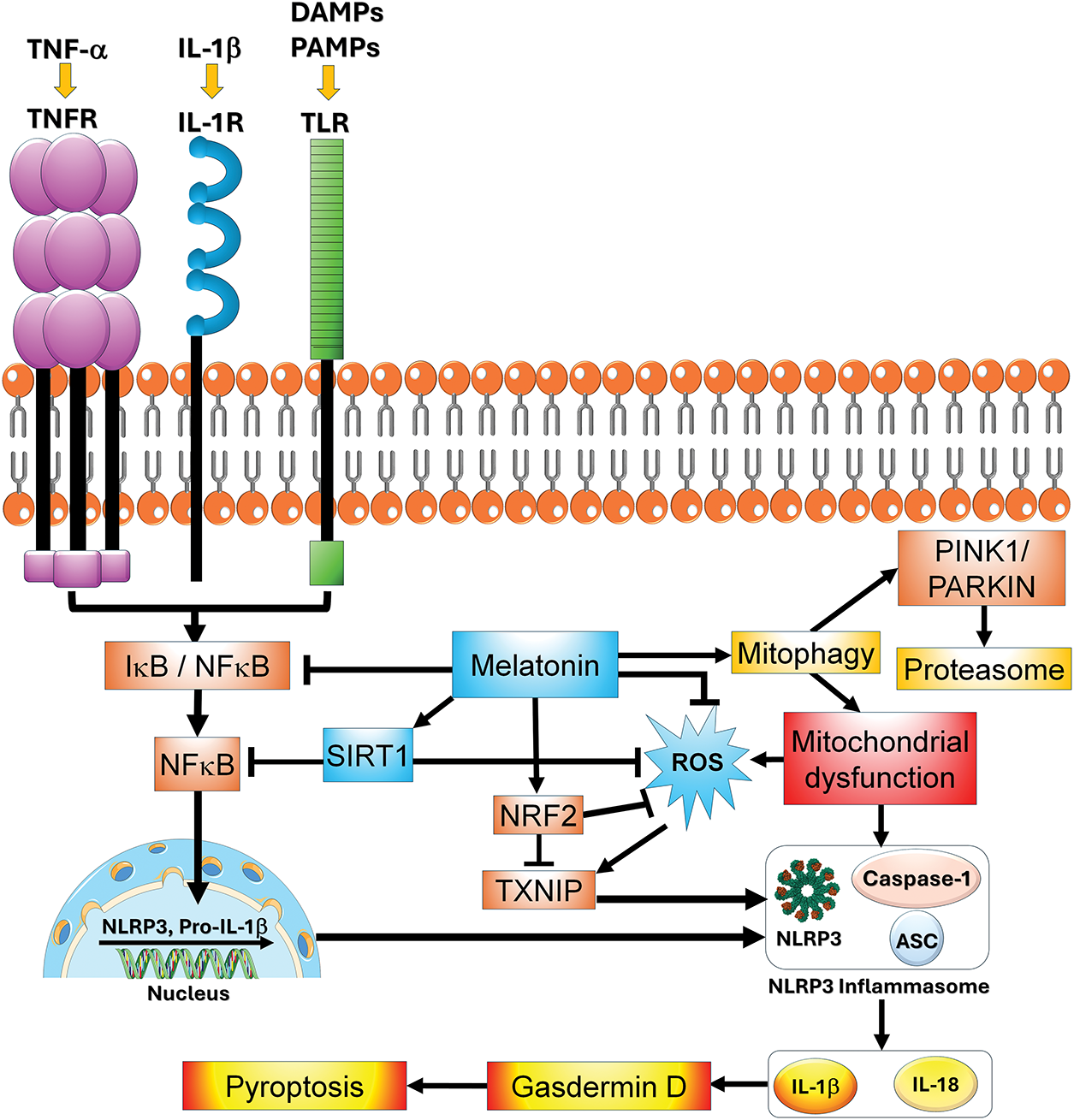

As pointed out, a prominent contributor to inflammation in both normal and tumor tissues is a result of the activation NF-κB (Fig. 7). This transcription factor is normally present in the cytosol in an inactive form where it is bound to inhibitory kappa B (IκB). When dislodged, it translocates to the nucleus where it binds to DNA sequences that promote the release pro-inflammatory mediators such as IL-6, IL-1 and TNFα [166,167]. Inflammatory cytokines are highly efficient at generating toxic free radicals and also indirectly function in the activation of the inflammasome [168]. The activated inflammasome stimulates additional pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-18 and IL-1β which further exaggerates the inflammatory response and aids in inducing cancer chemoresistance [169]. The collective actions of the inflammatory mediators conspire to sustain cancer drug resistance, advance the development of cancer stem cells which make the tumors less responsive to potential therapies, and create a cellular microenvironment that shelters the cancer cells from inhibitory drugs.

Figure 7: The influence of melatonin on the inflammasome and related processes are illustrated in this figure. Melatonin and its metabolites have several means by which it suppresses the inflammasome including the direct scavenging of ROS, inhibition of NF-κB signaling, and downregulation of TXNIP with the eventual reduction in pyroptosis. Given that inflammation plays a role in determining cancer cell chemoresistance, the ability of melatonin to modulate the inflammatory pathways summarized here provides one means by which it may contribute to tumor cells becoming resensitized to chemotherapeutic drugs. ASC = apoptosis-associated Speck-like protein containing a CARD; DAMPs = damage associated molecular patterns; IκB = inhibitory kappa B; IL-1β = interleukin-1beta; IL-18 = interleukin 18; IL-1R = interleukin receptor; NFκB = nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; Nrf2 = nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; TNFR = tumor necrosis factor receptor; PAMPs = pathogen associated molecular pattens; Parkin = E3 ubiquitin ligase; PINK1 = PTEN-induced kinase 1; ROS = reactive oxygen species; SIRT1 = sirtuin 1; TXNIP = thioredoxin interacting protein, TLR = Toll-like receptor

Melatonin’s actions on most aspects of cancer including those that contribute to tumor cell resistance to chemotherapies have been examined in many reports. Its ability to modulate immune responses and reduce inflammation by inhibiting NF-κB separation from IκB as well as prevent its heterodimerization with p50 and RelA and its translocation into the nucleus to activate pro-inflammatory genes has been well-documented [170,171]. The suppression of NF-κB by melatonin also inhibits expression of IL-1α, matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) and cyclin D, all of which are directly or indirectly involved in inflammation [172]. Additionally, melatonin inhibits nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain, leucine rich repeat, and pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) expression by pathways that involve silent information regular 2 homolog (SIRT1), long non-coding RNA, microRNA and wingless type (Wnt)/β-catenin [173].

There are several members of the inflammasome family, with the most extensively studied member being NLRP3, a component of the innate immune system. NLRP3 is a protein complex located in the cytosol that, when activated, induces the generation of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β which influences downstream pathways that advance inflammation, interfere with cell function and eventually cause cellular death due to pyroptosis (Fig. 7) [174,175]. This inflammasome complex includes a NOD-like-receptor (NLR), an effector protein, and an adaptor protein. It is activated by both intrinsic and extrinsic variables with major upregulators including ROS, danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), destabilization of lysosomes, and others [176]. Reducing inflammasome activation is clearly an effective means of limiting inflammatory disorders.

The use of melatonin to target inflammasome-mediated cytokine induced molecular damage has been an approach used in both in vitro and in vivo reports. A major activator of NLRP3 is the transcription of IL-1β by NF-κB; notably, NF-κB is also stimulated by IL-18 which induces the transcription of IFN-γ [177]. Melatonin suppression of the NLRP3 inflammasome involves both the direct inhibition of NF-κB signaling and SIRT1 mediated deacetylation of this transcription factor [177]. ROS, which are major triggers of NLRP3 upregulation, are directly neutralized by melatonin, thereby reducing inflammasome signaling. Additionally, melatonin indirectly suppresses ROS generation and NLRP3 activity by reducing the levels of thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) which normally stimulates NLRP3 [178]. The associations of melatonin with the NLRP3 inflammasome are graphically represented in Fig. 7.

In experimental pathophysiological models of disease, melatonin has proven effective in inhibiting inflammation in degenerative neurological conditions, sepsis-mediated inflammation, inflammatory conditions of the gastrointestinal tract, acute and chronic cardiovascular diseases and others [179,180]. Melatonin also inhibits cyclooxygenase 2 which plays a key role in inflammation [181]. Since inflammation is a major contributor to cancer drug chemoresistance [182], the ability of melatonin to modulate the associated inflammatory processes could be a significant factor in re-sensitizing cancer cells to conventional therapies.

5.11 Regulation of ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC) Transporters and Drug Efflux: Association with Chemoresistance

A primary mechanism of chemoresistance in cancer cells likely involves the overexpression of ABC transporters, which actively pump chemotherapeutic drugs out of cancer cells, reducing their intracellular concentration and therapeutic efficacy [183]. Several studies have demonstrated melatonin’s ability to downregulate the expression and function of ATP-binding cassette sub-family G member 2/breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2/BCRP), a key transporter associated with multidrug resistance (MDR). For example, Martín and colleagues found that melatonin significantly downregulated ABCG2/BCRP expression in brain tumor stem cells (BTSCs) and glioma cells, enhancing their sensitivity to chemotherapeutic agents such as temozolomide [184]. This downregulation was attributed to epigenetic modifications, specifically increased methylation of the ABCG2/BCRP promoter region. The effect was abolished by preincubation with a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor, confirming that DNA methylation plays a central role in melatonin’s mechanism of action.

Melatonin also downregulates MDR1, another crucial mediator of chemoresistance. In human myelogenous leukemia cells, melatonin treatment significantly decreased both the expression and activity of P-p, enhancing the cytotoxic effect of doxorubicin in resistant K562 cells [185], further supporting its potential. Cataldo and colleagues examined melatonin’s effects on chemoresistance in stem-like cells (spheres) derived from canine mammary carcinoma lines, CF41.Mg and REM134 [139]. They report that melatonin selectively modulates the expression of chemoresistance-associated genes in CF41.Mg-derived CSCs, although further optimization is needed to enhance its synergy with standard therapies. These findings highlight melatonin’s potential as an adjunct therapy for canine mammary tumors through its modulatory effects on CSC biology.

5.12 Circadian Rhythms and Chemoresistance

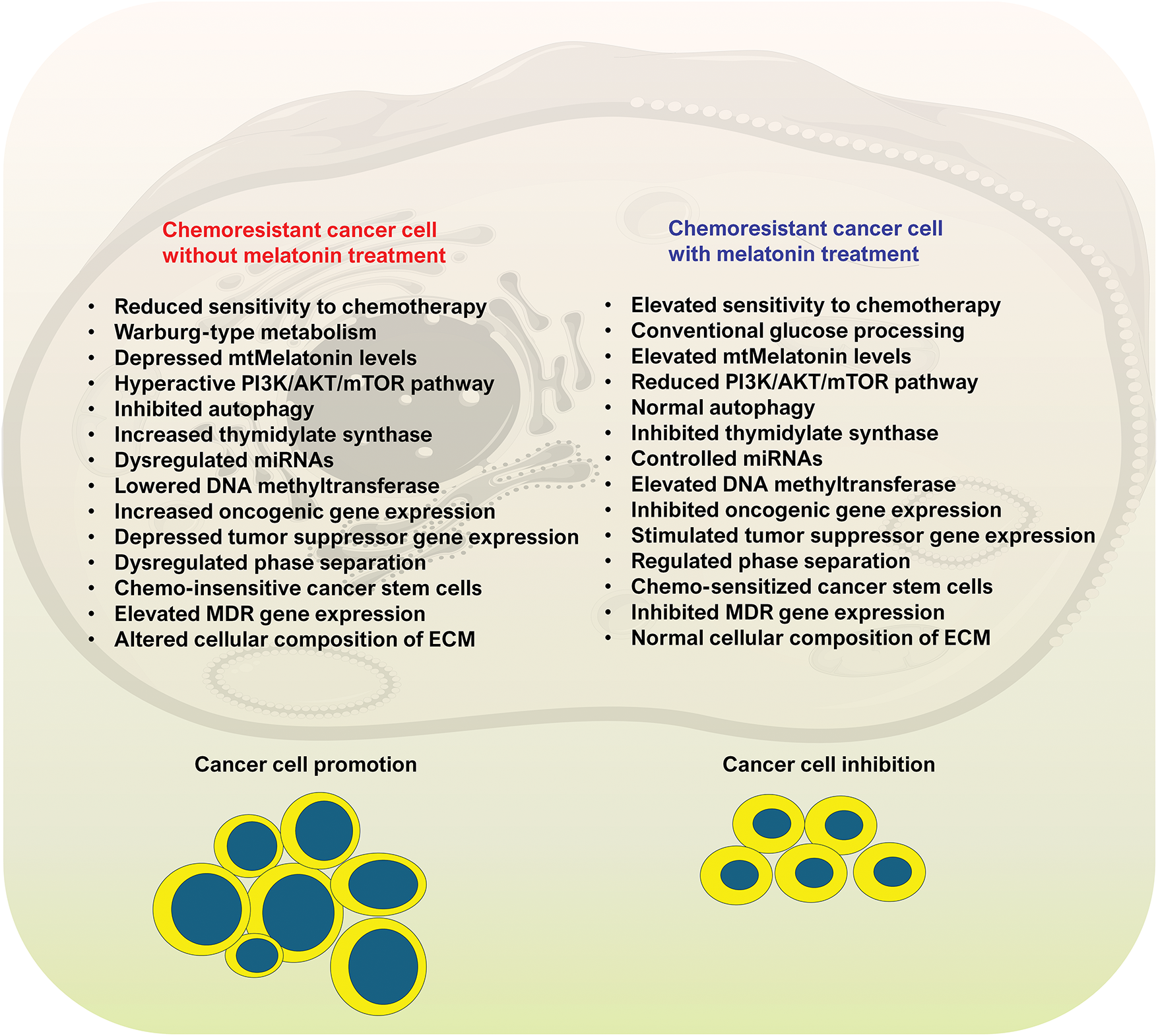

Finally, not to be overlooked are the circadian synchronizing actions of melatonin. Tumor cells possess clock genes which are influenced by melatonin and are involved in the cancer inhibiting effect of this indole. Whether this action of melatonin relates to the interruption of cancer cell chemoresistance has not been well investigated [186]. A summary of the multiple actions by which melatonin may alter cancer chemosensitivity are tabulated in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: Some of the identified metabolic changes in chemoresistance cancer cells and the changes induced by melatonin are summarized in this figure. On the left half of the figure are some of the perturbations that occur in cancer cells that presumably contribute to their chemo-insensitivity to oncostatic drugs. As shown on the right half of the figure, the metabolic alterations that become manifested in chemoresistant cancer cells are reversed by melatonin. The data supporting these observations are summarized in the current report. As listed, some of the changes are not specific since for some processes there are many factors involved, e.g., tumor stimulator and tumor suppressor genes. Likewise, the pattern of metabolic changes varies based on the cancer cell type, so this is a generalized list. It is important, however, that so many metabolic alterations that develop in cancer chemoresistant cells of various types are reversed following melatonin treatment. Two hallmarks of cancer include Warburg type metabolism and increased free radical generation in mitochondria, both of which are counteracted by melatonin

6 Concluding Remarks and Perspective

The loss of sensitivity of cancer cells to drugs normally used to control their growth continues to present a major obstacle for clinical oncologists. Thus, the importance of defining the mechanisms that initiate chemoresistance and identifying drugs that reverse the process cannot be overstated. Chemoresistance is, however, associated with a multitude of cellular and mitochondrial changes making it difficult to decipher which of the processes proposed is most relevant to drug resistance. Cancer cells exhibit a wide range of adaptive alterations, including metabolic reprogramming, evasion of apoptosis, altered DNA repair capacity, changes in drug transporters (e.g., overexpression of efflux pumps such as P-glycoprotein), epigenetic modifications, and disruptions in redox homeostasis. In particular, mitochondrial dysfunction plays a pivotal role in fostering resistance, as it contributes to metabolic shifts like the Warburg effect, elevates ROS production, and impairs apoptotic signaling (Fig. 8).

Among the many molecular factors implicated in the modulation of chemoresistance, melatonin, a naturally occurring molecule and potent mitochondria-targeted antioxidant, has emerged as a particularly intriguing candidate. Melatonin is well-documented for its role in regulating circadian rhythms, but it also exerts a wide range of cytoprotective effects, including the maintenance of mitochondrial integrity, scavenging of excessive ROS, and modulation of apoptosis-related pathways. Crucially, melatonin has been shown to influence several signaling cascades implicated in chemoresistance, notably the PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis. Activation of this pathway promotes cell survival, proliferation, and metabolic adaptation, all of which contribute to resistance against chemotherapeutic agents. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that melatonin can suppress this pro-survival signaling pathway, reduce the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl-XL, and enhance the susceptibility of cancer cells to apoptosis.

An emerging area of research that has potentially high relevance to melatonin and drug chemoresistance of tumor cells is the involvement of non-coding microRNAs. This field of research is expected to become increasingly significant due to the very large number that has been uncovered and to their multiple roles in silencing and regulating gene activity following transcription. The amount of information on the relationship of microRNAs to melatonin and chemoresistance is still meager, although some reports suggest that this field may become highly worthy of study [117,187].

Furthermore, melatonin’s impact extends to the regulation of the intracellular redox environment, which is intimately linked to drug sensitivity. By restoring redox balance, melatonin may indirectly attenuate aberrant activation of survival pathways like PI3K/AKT/mTOR and potentially re-sensitize cancer cells to chemotherapeutic agents. Additionally, emerging data suggests that melatonin can influence mitochondrial dynamics and biogenesis, thereby correcting mitochondrial dysfunctions that underlie many chemoresistant phenotypes.

Melatonin, as a natural molecule in all animals and plants, has a very high safety profile even when administered at very high pharmacological doses. Also, once taken up into cells, it distributes to all subcellular compartments unlike some other natural radical scavengers which are restricted to certain subcellular organelles because of their unique solubilities. Also, not only the parent molecule, melatonin, but many of its metabolic kin are likewise highly effective radical scavengers with some of them being more potent than melatonin itself. In addition to the receptor independent role of melatonin as a detoxifier of oxygen- and nitrogen- based reactants, melatonin induces other antioxidative processes via receptor mediated mechanisms.

Melatonin has often been used in human clinical trials [188–192]. These reports always included an assessment of the side effects and invariably the conclusion is that melatonin is uncommonly safe. Doses ranging from 1 mg to 1000 mg have been given to humans for extended durations without a mention of serious counter indications [193]. Idiosyncratic reactions have been noted in a couple of publications with one case report describing gynecomastia in a male subject [194] and one report of diarrhea [195]. When melatonin is used in disease treatment in humans, the most thoroughly calculated dose is estimated to be 1.0–1.5 mg per kg body weight [188]. Because of its circadian regulatory actions, melatonin is usually suggested to be used in the evening before bedtime. However, as the research moves forward, it may also be found to be useful if given during the day, for example, to protect against diagnostic radiation therapy or against toxic drugs that are administered at any time during the 24-h period.

Even though there are a large number of potential means by which melatonin may overcome chemoresistance, as summarized in this report, there is no definitive evidence for one potential mechanism being involved in lieu of another. In consideration of the multiple functions of this intrinsically produced molecule, it is possible that several actions conspire to modulate cancer cell chemoresistance. In light of the significant value of identifying new means to increase the sensitivity of cancer cells to treatment paradigms, a major goal of this review was to encourage the investigation of how melatonin may achieve a reversal of the ability of cancer cells to ignore the inhibitory actions of drugs to which they are otherwise susceptible.

Considering the vast amount of experimental data and some clinical findings suggesting an inhibitory action of melatonin on the initiation, progression, and metastatic potential of cancer along with its reversal of Warburg metabolism and its ability to overcome chemoresistance (and radioresistance), it should be given prior to the conduct of appropriate clinical trials. It is essential that these studies be adequately powered, that melatonin be tested at an appropriate dose [193], and that its administration is initiated before the final stage of the disease where essentially all treatments fail. Also, consideration should be given to timing and the route of melatonin administration and to the use of melatonin of different fabrications. For example, when complexed with various nanocarriers, melatonin has been shown to have increased efficacy, likely due to its more efficient distribution to the diseased site [117,196,197]. Nanocarriers have the advantage of providing targeted drug delivery, protecting the active agent from degradation, improving the solubility of the medication, and determining its release characteristics.

Taken together, these findings position melatonin as a promising adjuvant in cancer therapy, with the potential to overcome multiple resistance mechanisms simultaneously. Future investigations are warranted to systematically explore the extent to which melatonin supplementation, either alone or in combination with conventional chemotherapeutics, can reverse chemoresistance and improve clinical outcomes for patients battling refractory cancers.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Russel J. Reiter; Data curation: Russel J. Reiter, Ramaswamy Sharma, Walter Manucha, Walter Balduini, Doris Loh, Demetrios A. Spandidos, Alejandro Romero, Vasiliki E. Georgakopoulou, Wei Zhu; Software: Ramaswamy Sharma; Writing—original draft preparation: Russel J. Reiter, Doris Loh, Wei Zhu, Vasiliki E. Georgakopoulou; Writing—review and editing: Russel J. Reiter, Ramaswamy Sharma, Walter Manucha, Walter Balduini, Doris Loh, Demetrios A. Spandidos, Alejandro Romero, Vasiliki E. Georgakopoulou, Wei Zhu; Supervision: Russel J. Reiter. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| 5-HT | 5-hydroxytryptamine |

| 8-OHdG | 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine |

| AADC | Amino acid decarboxylase |

| AANAT | Aralkylamine N-acetyltransferase |