Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Esculetin Ameliorates Cisplatin-Induced Acute Kidney Injury by Inhibiting Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Tubular Cell Death in Mice

Department of Immunology, Daegu Catholic University School of Medicine, Daegu, 42472, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Jaechan Leem. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Modulation of Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Mitochondrial Function: Therapeutic Perspectives Across Diseases)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(11), 2147-2166. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.070188

Received 10 July 2025; Accepted 19 September 2025; Issue published 24 November 2025

Abstract

Background: Cisplatin (CDDP) is a cornerstone chemotherapeutic agent for many solid tumors, but its clinical use is severely limited by dose-dependent nephrotoxicity, which results in acute kidney injury (AKI) in a significant proportion of patients. CDDP-induced AKI involves interconnected mechanisms, including inflammation, oxidative stress, and tubular cell death. In this study, we aimed to investigate the renoprotective effects of esculetin (ES), a natural antioxidant coumarin, in a murine model of CDDP-induced AKI. Methods: Male C57BL/6 mice (8–10 weeks) received a single intraperitoneal injection of CDDP (20 mg/kg) with or without ES (40 mg/kg/day, oral gavage). Renal function, histopathology, and molecular markers of inflammation, oxidative stress, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, apoptosis, and ferroptosis were assessed by standard biochemical, histological, and immunoblotting techniques. Results: ES significantly reduced CDDP-induced elevations in serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen, preserved renal structure, and decreased histological injury scores. Molecular analyses showed that ES suppressed the production of systemic and renal proinflammatory cytokines and inhibited the expression of chemokines and adhesion molecules. ES also suppressed the phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and p38 MAPKs, mitigating stress-induced inflammatory and apoptotic signaling. Additionally, ES treatment reduced the expression of unfolded protein response markers, such as C/EBP homologous protein, which is indicative of alleviated ER stress. Oxidative injury was reduced, as evidenced by lower malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxynonenal levels and restored glutathione content. Importantly, ES mitigated ferroptosis, as demonstrated by decreased expression of pro-ferroptotic markers and preservation of anti-ferroptotic mediators, including glutathione peroxidase 4 and solute carrier family 7 member 1. Conclusion: Collectively, our findings provide the first in vivo evidence that ES robustly protects against CDDP-induced AKI by simultaneously targeting oxidative stress, inflammation, MAPK, and ER stress pathways, apoptosis, and ferroptosis. These results highlight ES as a potential candidate for preventing CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity.Keywords

Cisplatin (CDDP) is a potent and commonly used chemotherapeutic agent for the treatment of multiple solid malignancies, including testicular, ovarian, bladder, and head and neck cancers [1]. Its antitumor efficacy primarily stems from its ability to induce DNA cross-linking, thereby disrupting DNA replication and transcription in rapidly proliferating cells [1,2]. Despite its widespread use, the clinical use of CDDP is largely restricted by its dose-dependent nephrotoxicity, which manifests predominantly as acute kidney injury (AKI) in about 20%–30% of treated patients [3].

CDDP-induced AKI is a multifactorial pathological condition resulting from a complex interplay of cellular stress responses and death pathways [2,4]. One of the earliest events following CDDP administration is the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to oxidative stress and widespread damage to cellular macromolecules [5]. This oxidative injury disrupts mitochondrial function and bioenergetic balance, thereby sensitizing renal tubular epithelial cells to further damage. In parallel, CDDP exposure initiates a robust inflammatory response marked by the release of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and the upregulation of adhesion molecules, leading to leukocyte infiltration into the kidney [2,4]. This inflammatory cascade is orchestrated in part by the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling cascades, which link extracellular stress signals to inflammatory gene expression and contribute to both inflammation and cell death [2].

A crucial intracellular mechanism linking oxidative and inflammatory stress to cell death is endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress [6]. CDDP disrupts ER homeostasis by impairing protein folding capacity and promoting the buildup of unfolded or misfolded proteins, which trigger the unfolded protein response (UPR) [7]. While the UPR initially serves a protective function, prolonged or overwhelming ER stress shifts the balance toward proinflammatory and pro-apoptotic signaling [6]. Specifically, ER stress exacerbates inflammation by upregulating cytokine production while simultaneously activating pro-apoptotic mediators and downstream effector molecules, thereby contributing to tubular epithelial cell death [7,8]. Ultimately, these converging mechanisms culminate in tubular cell death, predominantly through apoptosis. In addition to apoptosis, ferroptosis, a distinct, iron-dependent form of regulated necrosis characterized by glutathione (GSH) depletion and lipid peroxidation, has also been implicated in CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity [9]. Ferroptotic death lacks classical apoptotic features but results in catastrophic membrane injury, offering a complementary pathway through which CDDP induces renal dysfunction. Taken together, the overlapping contributions of oxidative stress, inflammation, and multiple forms of tubular cell death illustrate the complex pathogenesis of CDDP-induced AKI. These insights underscore the need for nephroprotective interventions capable of simultaneously modulating these interconnected pathways to effectively preserve renal function.

Natural compounds with intrinsic antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties have garnered attention as promising alternatives for attenuating CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity [9]. Esculetin (6,7-dihydroxycoumarin; ES) is a naturally occurring coumarin compound found in various traditional medicinal plants [10]. ES has been recognized for its pharmacological versatility, exhibiting anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-tumor activities across multiple experimental models [11,12]. As an effective free radical scavenger, ES can reduce oxidative damage and support cellular homeostasis under stress conditions [13,14]. In addition, its anti-inflammatory actions have been evidenced by the suppression of key proinflammatory mediators such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and IL-6 in rodent models of cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury [15], mastitis [16], acute lung injury [17,18], sepsis [19], and neuroinflammation [20]. These multifaceted protective properties suggest a potential therapeutic role for ES in conditions where oxidative stress and inflammation are central pathogenic factors.

Although ES has shown renoprotective activity in lupus nephritis as well as metabolic and ischemic kidney injury models [21–23], its efficacy in chemotherapy-associated nephrotoxicity, particularly CDDP-induced AKI, remains unexplored in vivo. Available data are largely limited to a few in vitro studies in various cell types, suggesting that ES may exert cytoprotective effects under oxidative stress and inflammatory conditions [24–26]. This highlights a clear gap in understanding how ES might modulate the multifactorial injury mechanisms that characterize CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity. Based on this rationale, we investigated the renoprotective potential of ES in a murine model of CDDP-induced AKI. Based on its well-established antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [11], we hypothesized that ES would ameliorate CDDP-induced renal injury by suppressing inflammation, reducing oxidative stress, and mitigating tubular epithelial cell death.

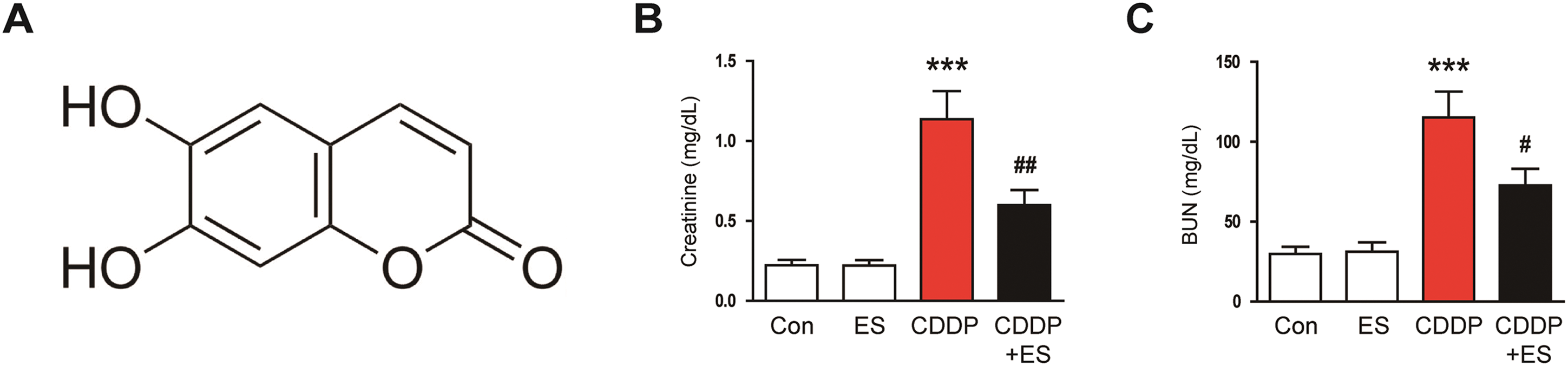

ES (purity ≥95%) was acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (PHL80449, St. Louis, MO, USA). The chemical structure of ES is shown in Fig. 1A. CDDP was also purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (P4394). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) reagents were obtained from BBC Biochemical (Mount Vernon, WA, USA; MA0101010 for hematoxylin and 3610 for eosin). Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) reagent was also purchased from BBC Biochemical (SKC1071-500). For immunohistochemistry (IHC), the primary antibody against neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) was acquired from Invitrogen (PA5-79590, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and the antibody against 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) was obtained from Bioss (BS-6313R, Woburn, MA, USA). A goat-sourced anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody linked to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) for IHC was acquired from Abcam (ab6721, Cambridge, MA, USA). For Western blot analysis, primary antibodies against cleaved caspase-3 (9661), p53 (2524), phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (p-ERK1/2; 9101), ERK1/2 (9102), phosphorylated p38 (p-p38; 9211), p38 (9212), phosphorylated protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (p-PERK; 3179), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 5174) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Antibodies against neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL; sc-515876) and PERK (sc-377400) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA), while antibodies against activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6; ab37149) and transferrin receptor 1 (TFR1; ab269513) were purchased from Abcam. The C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) antibody (MA1-250) was obtained from Invitrogen, and the antibody against solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) was purchased from Proteintech (32384-1-AP, Rosemont, IL, USA). HRP-linked goat anti-rabbit IgG (7074) and horse anti-mouse IgG (7076) antibodies applied for western blotting were sourced from Cell Signaling Technology.

Figure 1: Esculetin (ES) alleviates renal dysfunction and histological abnormalities in Cisplatin (CDDP)-challenged mice. (A) Chemical structure of ES. (B) Serum creatinine levels (indicator of renal filtration function, n = 8). (C) Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels (maker of renal dysfunction, n = 8). (D) Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)- and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-stained renal tissue sections. Scale bars = 40 μm. (E) Tubular injury scores (n = 8). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001 vs. Con; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 vs. CDDP

All in vivo procedures received ethical approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Daegu Catholic University Medical Center (approval number: DCIAFCR-240102-35-Y) and adhered to the guidelines outlined in the 8th edition of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, Washington, DC, USA). Seven-week-old male C57BL/6 mice were obtained from HyoSung Science (Daegu, Republic of Korea). Upon arrival, the animals were maintained under standardized conditions, including a temperature-controlled environment (20°C–24°C), relative humidity of approximately 55%, and a controlled 12-h light/dark photoperiod, followed by a one-week acclimation period prior to experimentation. A regular rodent diet and water were available to the mice at all times during the study. After acclimation, the mice were distributed at random into four groups, each consisting of eight animals, as follows: Control group (no intervention), ES group (esculetin only), CDDP group (cisplatin only), and CDDP + ES group (combined treatment). ES was orally administered at 40 mg/kg once daily via gavage for four consecutive days, starting on the first day of treatment and continuing through the fourth day. CDDP was administered as a single intraperitoneal injection (20 mg/kg) on the second treatment day [27]. In the combined treatment group, ES was administered one hour prior to CDDP injection on the second day and was continued daily thereafter until the end of the four-day dosing period. The planned group size (n = 8) was informed by previous murine studies employing ES in inflammatory disease models that reported consistent efficacy with 6–10 animals per group [19–21]. An a priori power calculation was not performed because the present study was exploratory and aimed to interrogate mechanistic outcomes across multiple parameters. The dose of ES was determined based on previous studies in mice showing reliable efficacy and tolerability in inflammatory injury models within the 20–40 mg/kg range [18–21]. Using allometric scaling (mouse Km = 3; human Km = 37) [28], the human-equivalent dose (HED) of 40 mg/kg in mice corresponds to approximately 3.2 mg/kg, which is within a clinically feasible range for further translational development. All mice were euthanized humanely 72 h after CDDP injection, corresponding to the fifth day of the treatment schedule. Deep anesthesia was induced via intraperitoneal injection of freshly prepared 1.25% Avertin (Sigma-Aldrich, T48402) in 2-methyl-2-butanol. Immediately afterward, blood and kidney tissues were harvested for subsequent biochemical, histological, and molecular analyses.

Serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) concentrations were determined using colorimetric detection kits (Invitrogen; EIASCR for creatinine and EIABUN for BUN), following the manufacturer’s protocols. IL-1β (MLB00C-1), TNF-α (MTA00B-1), and IL-6 (M6000B-1) concentrations in blood serum and renal homogenates were analyzed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Renal malondialdehyde (MDA) levels were assessed with a lipid peroxidation assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich, MAK085), and GSH levels were determined using a commercial detection kit (Enzo Life Sciences, ADI-900-160, Farmingdale, NY, USA), following the respective protocols.

2.4 Histological Evaluation and IHC

Following fixation in 1% formalin, kidney specimens underwent ethanol dehydration, xylene clearing, and paraffin embedding. Thin sections were prepared and mounted on glass slides. For histological evaluation, sections were stained with H&E and PAS reagents to examine renal tubular damage. Tubular injury was appraised in five random fields (400× magnification) per section using an established semi-quantitative grading scale ranging from 0 to 4: 0 = no damage; 1 = injury in <25% of tubules; 2 = 25%–50%; 3 = 50%–75%; and 4 = >75%, based on features such as lumen dilatation and cast formation [29]. For IHC analysis, deparaffinization and rehydration were performed using standard procedures, followed by antigen retrieval in citrate buffer under heat. Endogenous peroxidase activity was inhibited, and nonspecific antibody binding was minimized by blocking before antibody incubation. Sections were treated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies specific for NGAL (1:200) or 4-HNE (1:200). After thorough washing, an HRP-linked goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:500) was employed. For quantitative analysis, the positively stained areas for NGAL and 4-HNE were measured using digital image analysis software (version 11.0; IMT i-Solution, Coquitlam, BC, Canada) in five random fields per sample at 400× magnification. Results were reported as the percentage of positive staining within each observed field.

2.5 Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase dUTP Nick End Labeling (TUNEL) Staining

To assess apoptosis in renal tissue, TUNEL staining was carried out using a commercially available kit (Roche Diagnostics, 11684795910, Indianapolis, IN, USA) in accordance with the supplier’s protocol. Paraffin-embedded kidney tissues underwent deparaffinization and rehydration through graded alcohols, followed by a 30-min permeabilization step in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer at ambient temperature. After thorough washing in phosphate-buffered saline, TUNEL labeling was conducted by incubating the sections with the reaction reagent at 37°C for 60 min in a humidified chamber. Cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI to visualize all cells, and fluorescent images were acquired using an A1 + confocal laser scanning microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). TUNEL-positive nuclei were counted in five random fields per tissue section at 600× magnification.

Kidney tissues were lysed in RIPA buffer and subsequently centrifuged to isolate protein lysates. Equivalent protein amounts were denatured and subjected to gel electrophoresis, followed by transfer onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked using 5% non-fat dry milk dissolved in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST), followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with primary antibodies targeting NGAL (1:500), cleaved caspase-3 (1:1000), p53 (1:1000), p-ERK1/2 (1:1000), ERK1/2 (1:1000), p-p38 (1:1000), p38 (1:1000), p-PERK (1:1000), PERK (1:500), ATF6 (1:1000), CHOP (1:500), TFR1 (1:1000), SLC7A11 (1:500), and GAPDH (1:2000). After thorough TBST washing, membranes were exposed to HRP-linked anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG secondary antibodies (1:2000) for 1 h at ambient temperature. Protein bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 32106, Waltham, MA, USA) and imaged using a digital imaging system. Densitometric analysis was conducted using ImageJ software (version 1.53j; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA), and protein levels were normalized to GAPDH.

2.7 Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR)

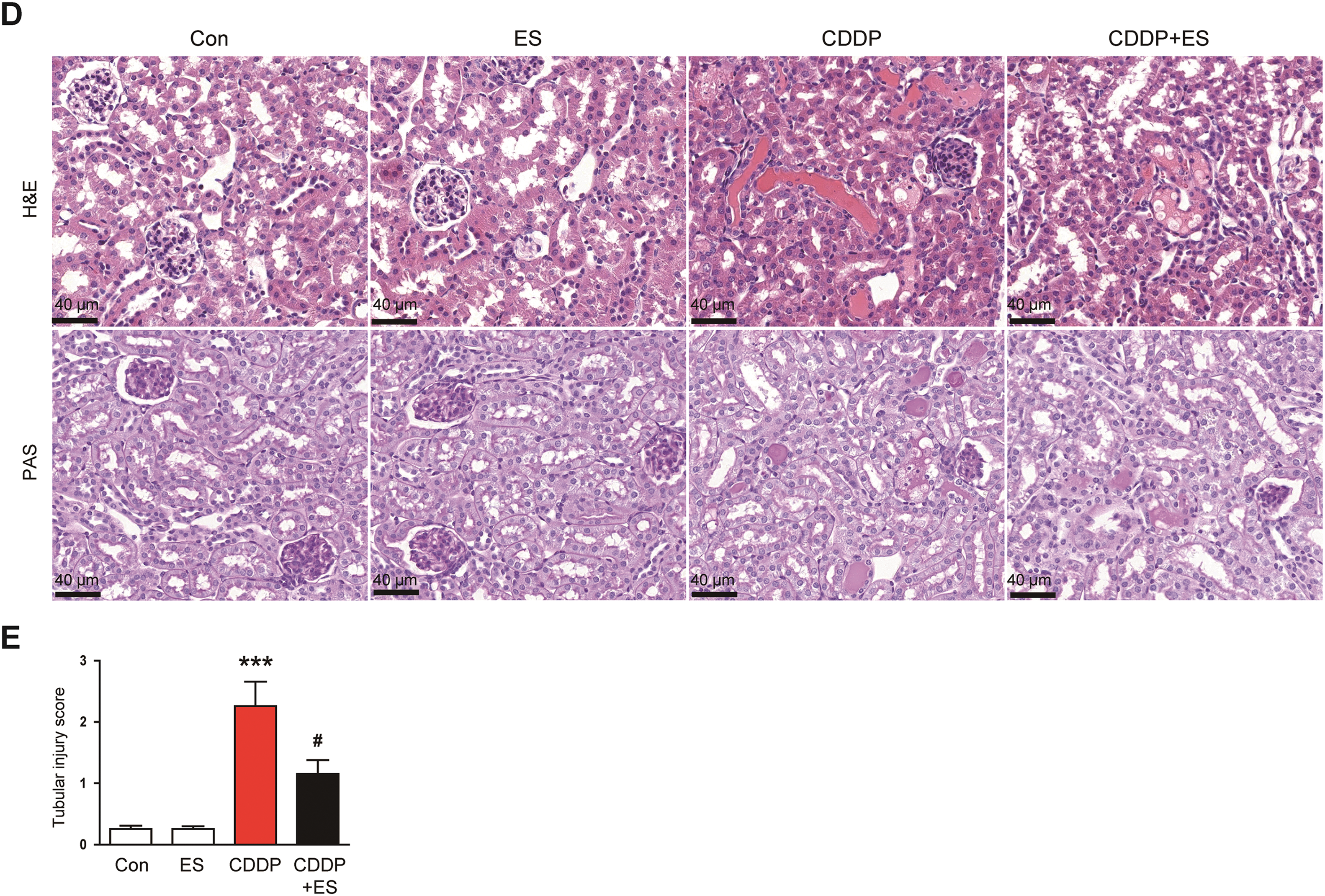

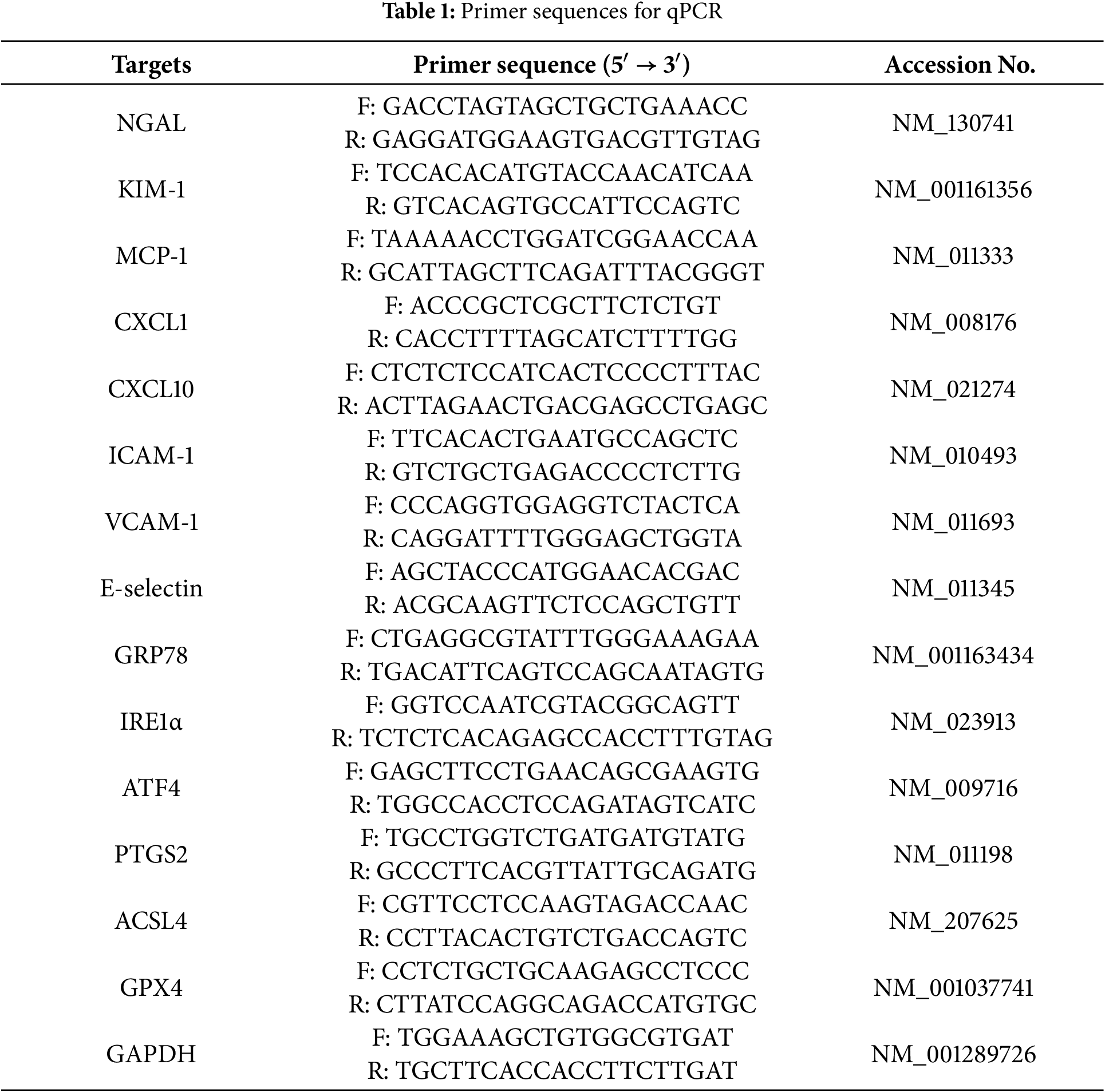

Kidney tissues were processed for total RNA extraction using TRIzol reagent, based on the standard phenol–chloroform method. The quality and concentration of RNA were assessed spectrophotometrically. Reverse transcription was performed to synthesize cDNA from 1 μg of total RNA using the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (TaKaRa, RR037A, Tokyo, Japan), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR was conducted using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 4367660, Waltham, MA, USA) on a Thermal Cycler Dice Real-Time System III (TaKaRa). The primer sequences are provided in Table 1. Relative mRNA levels were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method. GAPDH was used as the internal control.

All results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism software (version 8.0; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. For datasets exhibiting normal distribution, group differences were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. When normality assumptions were not met, the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied, followed by Dunn’s test for pairwise comparisons. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.1 ES Improves CDDP-Induced Renal Dysfunction and Histological Damage

Fig. 1A shows the chemical structure of ES. To evaluate the influence of ES on renal function in CDDP-induced AKI, serum creatinine and BUN concentrations were assessed. Mice administered CDDP alone exhibited a significant rise in both serum creatinine and BUN levels compared to controls (Fig. 1B,C). In contrast, ES treatment significantly reduced these elevations (Fig. 1B,C), suggesting that ES ameliorates CDDP-induced renal dysfunction. In line with the functional data, histological examination revealed a substantial increase in tubular injury score in the CDDP group (Fig. 1D,E). Notably, ES treatment significantly reduced the tubular injury score (Fig. 1D,E), indicating preserved renal morphology and structural integrity. Importantly, ES alone had no significant effect on serum creatinine, BUN levels, or tubular injury scores compared to the control group (Fig. 1B–E), demonstrating no adverse or stimulatory effects under physiological conditions. These findings collectively suggest that ES confers significant protection against CDDP-induced renal injury, both functionally and histologically, without affecting baseline renal homeostasis.

3.2 ES Mitigates Tubular Injury and Apoptotic Cell Death in CDDP-Treated Kidneys

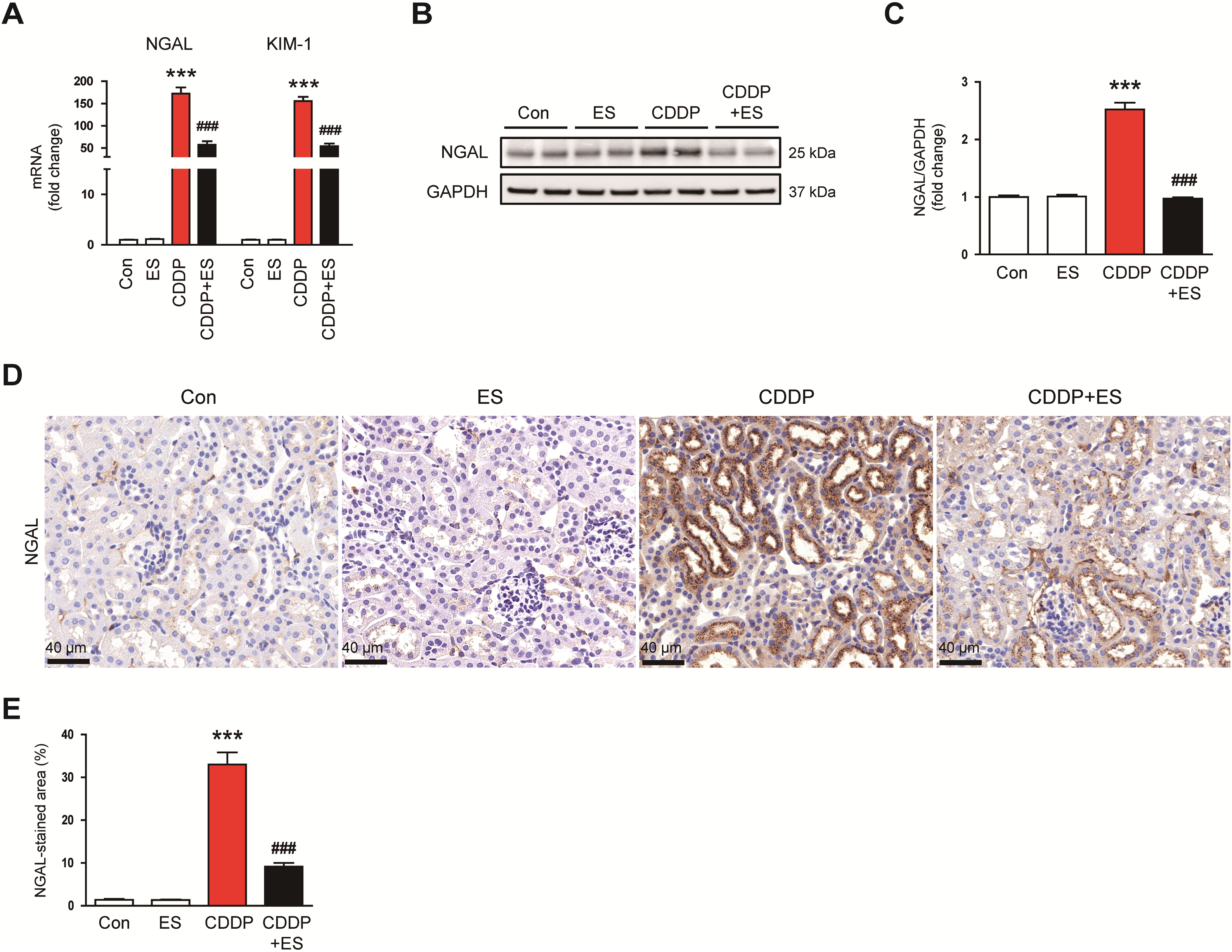

To further investigate the protective effects of ES on renal tubules, we examined the expression of key markers associated with tubular injury. CDDP treatment significantly increased the mRNA expression levels of NGAL and kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1), whereas ES treatment effectively suppressed this upregulation (Fig. 2A). Western blot analysis consistently showed elevated NGAL protein expression in the kidneys of CDDP-treated mice compared to controls (Fig. 2B,C). This increase was significantly attenuated by ES treatment, suggesting that ES mitigates CDDP-induced tubular damage. Furthermore, IHC staining demonstrated increased NGAL expression in tubular epithelium following CDDP exposure, which was also attenuated in the ES-treated group (Fig. 2D,E).

Figure 2: ES reduces the expression of tubular injury markers in CDDP-challenged mice. (A) Relative mRNA expression levels of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) and kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1) in kidney tissues (n = 8). (B,C) Western blot analysis and densitometric quantification of NGAL in kidney tissues (n = 6). (D) Representative immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of NGAL in kidney tissues. Scale bars = 40 μm. (E) Quantification of NGAL-positive areas (n = 8). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001 vs. Con; ###p < 0.001 vs. CDDP

To evaluate apoptotic cell death, TUNEL staining was performed. The CDDP group showed a robust increase in TUNEL-positive tubular nuclei (Fig. 3A,B). This apoptotic response was significantly diminished by ES treatment, reflecting the anti-apoptotic effects of ES. In line with these observations, cleaved caspase-3 and p53 levels were found to be elevated in response to CDDP treatment (Fig. 3C,D). ES treatment significantly reduced the expression of all three apoptotic markers, further supporting its role in suppressing apoptosis in damaged renal tissue.

Figure 3: ES inhibits apoptotic cell death in CDDP-challenged mice. (A) Representative images of kidney sections stained with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL). Scale bars = 50 μm. (B) Quantification of TUNEL-positive cells per field (n = 8). (C,D) Western blot analysis and densitometric quantification of cleaved caspase-3 and p53 in kidney tissues (n = 6). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001 vs. Con; ###p < 0.001 vs. CDDP

3.3 ES Suppresses Inflammatory Responses in CDDP-Induced AKI

CDDP-induced AKI is closely linked to an intense inflammatory response marked by the production of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and endothelial adhesion molecules [2,4]. To determine whether ES modulates this inflammatory cascade, we evaluated systemic and renal expression of key inflammatory mediators. CDDP administration led to a significant elevation in serum levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 (Fig. 4A). ES treatment significantly reduced these cytokine levels, suggesting that ES mitigates systemic inflammation (Fig. 4A). Consistently, protein expression of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 in kidney homogenates was also markedly upregulated by CDDP and notably suppressed by ES treatment (Fig. 4B). To further examine the inflammatory microenvironment, mRNA expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1), and CXCL10 was assessed. All three chemokines were markedly upregulated in the kidneys of CDDP-treated mice, which was reversed by ES treatment (Fig. 4C). In addition, CDDP enhanced the renal mRNA expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), and E-selectin, while ES significantly suppressed their upregulation (Fig. 4D). Collectively, these data suggest that ES exhibits potent anti-inflammatory activity by reducing systemic and local cytokine production, and by downregulating chemokines and adhesion molecules.

Figure 4: ES mitigates inflammatory responses in CDDP-challenged mice. (A) Serum levels of interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and IL-6 (n = 8). (B) Relative mRNA expression levels of these cytokines in kidney tissues (n = 8). (C) Relative mRNA expression levels of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1), and CXCL10 in kidney tissues (n = 8). (D) Relative mRNA expression levels of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), and E-selectin in kidney tissues (n = 8). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001 vs. Con; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. CDDP

3.4 ES Attenuates MAPK Activation and ER Stress in CDDP-Treated Kidneys

To elucidate the mechanisms underlying the anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective action of ES, we examined the activation of MAPK signaling cascades. Among the MAPK family, ERK1/2 and p38 are well-documented mediators of CDDP-induced renal inflammation and tubular damage [30,31]. Western blot analysis showed a marked increase in the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and p38 in the kidneys of CDDP-treated mice, whereas ES treatment significantly suppressed this activation (Fig. 5A,B). We next investigated whether ES modulates ER stress, a key contributor to CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity [7,8]. Renal transcripts of glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), inositol-requiring enzyme 1 alpha (IRE1α), and activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) were markedly increased in CDDP-treated mice (Fig. 5C–E). These transcriptional responses were significantly blunted by ES treatment, suggesting that ES suppresses ER stress initiation (Fig. 5C–E). Furthermore, CDDP elevated the protein expression of p-PERK, ATF6, and CHOP, which were significantly reduced by ES treatment (Fig. 5F,G). Collectively, these findings indicate that ES protects against CDDP-induced renal injury by suppressing MAPK activation and reducing ER stress responses.

Figure 5: ES suppresses mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress activation in CDDP-challenged mice. (A,B) Western blot analysis and densitometric quantification of phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (p-ERK) and p-p38 in kidney tissues (n = 6). (C–E) Relative mRNA expression levels of glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), and activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) in kidney tissues (n = 8). (F,G) Western blot analysis and densitometric quantification of phosphorylated protein kinase R–like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (p-PERK), activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), and C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) in kidney tissues (n = 6). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001 vs. Con; ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. CDDP

3.5 ES Alleviates Oxidative Stress in CDDP-Induced AKI

Oxidative stress is a central pathological mechanism in CDDP-induced AKI, largely driven by the overproduction of ROS and lipid peroxidation [4]. To evaluate whether ES alleviates oxidative renal injury, we assessed established markers of oxidative stress in kidney tissues. IHC staining for 4-HNE, a reactive aldehyde byproduct of lipid peroxidation, revealed minimal expression in the control and ES-alone groups, but a pronounced increase in renal tubular cells in the CDDP group (Fig. 6A,B). Notably, ES treatment significantly reduced 4-HNE accumulation compared to the CDDP group, suggesting attenuation of ROS-induced lipid peroxidation (Fig. 6A,B). To further quantify lipid peroxidation, MDA levels were measured. Renal MDA concentrations were markedly elevated in the CDDP group, reflecting extensive oxidative membrane damage (Fig. 6C). This increase was significantly suppressed by ES treatment (Fig. 6C). Additionally, we measured the levels of GSH, a key intracellular antioxidant that is typically depleted under oxidative stress. GSH levels were markedly decreased in CDDP-treated kidneys, while ES treatment markedly restored GSH content, further supporting the antioxidant capacity of ES (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6: ES attenuates oxidative stress in CDDP-challenged mice. (A) Representative IHC staining of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE, a lipid peroxidation marker) in kidney tissues. Scale bars = 40 μm. (B) Quantification of 4-HNE-positive areas (n = 8). (C) Renal malondialdehyde (MDA, a byproduct of lipid peroxidation) levels (n = 8). (D) Renal glutathione (GSH, a major intracellular antioxidant) levels (n = 8). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001 vs. Con; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. CDDP

3.6 ES Inhibits Ferroptotic Cell Death in CDDP-Treated Kidneys

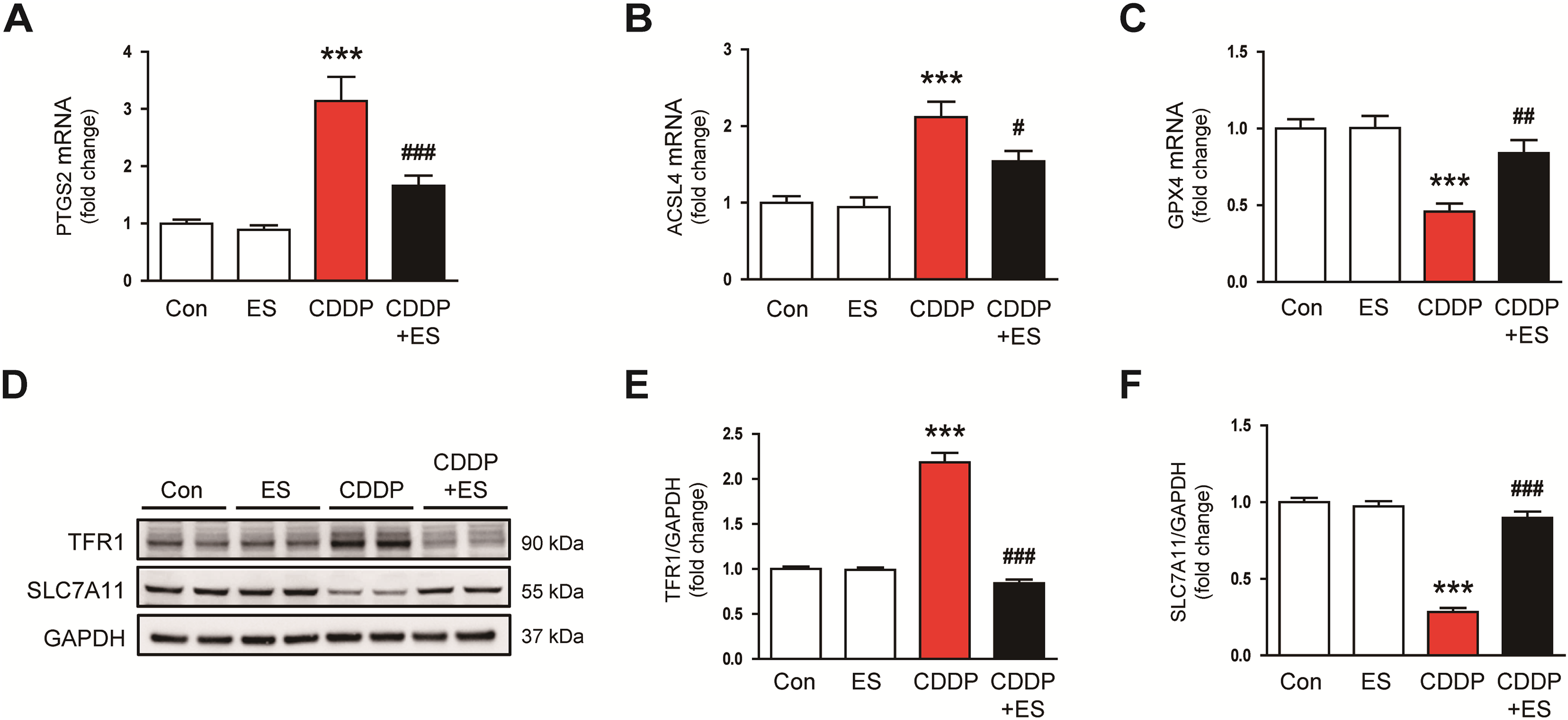

Ferroptosis, an iron-dependent type of regulated necrosis characterized by lipid peroxidation and GSH depletion, has been increasingly implicated in CDDP-induced AKI [9]. To determine whether ES attenuates ferroptotic cell death, we evaluated key markers involved in ferroptosis regulation. CDDP administration significantly upregulated prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2), a surrogate marker commonly associated with ferroptosis-induced stress responses, as well as acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4), which promotes the incorporation of polyunsaturated fatty acids into membrane phospholipids, thereby promoting lipid peroxidation (Fig. 7A,B). Conversely, mRNA levels of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), a key anti-ferroptotic enzyme, were significantly decreased by CDDP (Fig. 7C). ES treatment markedly reversed these changes, suppressing PTGS2 and ACSL4 expression while preserving GPX4 transcript levels. (Fig. 7A–C). Western blot analysis showed that CDDP increased the expression of TFR1, a facilitator of cellular iron uptake, while decreasing the expression of SLC7A11, a cystine/glutamate antiporter that maintains intracellular GSH levels and ferroptosis resistance (Fig. 7D–F). ES treatment significantly reduced TFR1 levels and restored SLC7A11 expression (Fig. 7D–F). Collectively, these results suggest that ES inhibits multiple steps of the ferroptosis cascade in CDDP-induced renal injury by maintaining the expression of GPX4 and SLC7A11, suppressing pro-ferroptotic mediators such as PTGS2, ACSL4, and TFR1.

Figure 7: ES prevents ferroptosis in CDDP-challenged mice. (A–C) Relative mRNA expression levels of prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2), acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4), and glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) in kidney tissues (n = 8). (D–F) Western blot analysis and densitometric quantification of transferrin receptor 1 (TFR1) and solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) in kidney tissues (n = 6). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ***p < 0.001 vs. Con; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 vs. CDDP

In this study, we demonstrated that ES confers significant renoprotective effects in a murine model of CDDP-induced AKI. ES treatment mitigated key pathological outcomes, including renal dysfunction, tubular epithelial injury, and apoptosis. These protective effects were accompanied by suppression of upstream pathophysiological mechanisms, including inflammation, oxidative stress, ER stress, and ferroptosis. Specifically, ES reduced serum creatinine and BUN levels, preserved renal histoarchitecture, and downregulated tubular injury markers. It also significantly decreased the number of TUNEL-positive tubular cells and attenuated the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins. These findings collectively suggest that ES exerts multifaceted protective actions by targeting interconnected pathways involved in renal injury, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic agent against CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity.

One key aspect of ES’s renoprotection is the mitigation of tubular damage and apoptosis caused by CDDP. ES treatment significantly suppressed the rise in NGAL and KIM-1 levels that was observed in CDDP-challenged mice. These markers are widely used to reflect proximal tubule damage in AKI and are known to be elevated by CDDP-induced stress [32]. Correspondingly, tubular injury scores were lower in ES-treated kidneys, indicating preservation of tubular structure. Importantly, ES also reduced tubular cell apoptosis, as evidenced by fewer TUNEL-positive nuclei and the downregulation of cleaved caspase-3 and p53. Activation of the p53-dependent intrinsic apoptotic pathway by CDDP in renal tubular cells contributes directly to mitochondrial dysfunction and tubular apoptosis, both key mechanisms in the pathogenesis of CDDP-induced AKI [33]. ES suppresses p53 accumulation and caspase-3 cleavage, which in turn interrupts the apoptotic cascade and promotes tubular cell survival. This anti-apoptotic effect of ES aligns with its overall cytoprotective profile and is consistent with findings for other natural compounds, such as luteolin and apigenin, which attenuate CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity by inhibiting p53-dependent tubular apoptosis [34,35].

Our data further emphasize the strong anti-inflammatory potential of ES in the context of CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity. CDDP administration elicited a pronounced inflammatory response, as indicated by elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines in both serum and kidney tissue. In line with this, CDDP-treated mice exhibited significant upregulation of chemokines and adhesion molecules, which are key mediators of immune cell recruitment to injured renal tissue. These cytokines and chemokines collectively drive the infiltration and activation of leukocytes, sustaining renal inflammation and exacerbating tissue damage [2,4]. Remarkably, ES treatment attenuated these inflammatory responses at both systemic and local levels. ES significantly reduced circulating and renal concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines and suppressed the expression of chemotactic and adhesive molecules. These results suggest that ES interrupts the self-amplifying inflammatory cascade triggered by CDDP, likely through suppression of upstream signaling pathways governing cytokine and chemokine production. Consistent with our results, previous studies have demonstrated that ES inhibits the release of proinflammatory mediators in immune cells [19,36].

Another mechanism by which ES confers renoprotection is through the modulation of stress signaling pathways that are activated by CDDP. We found that CDDP triggered pronounced activation of ERK1/2 and p38 in kidney tissue, as shown by increased phosphorylation of these kinases. This finding is consistent with the known role of CDDP-induced cellular stress in activating MAPK cascades within renal tubular epithelial cells [37]. Among the MAPK family, ERK1/2 and p38 play central roles in mediating inflammatory responses and apoptotic signaling during AKI [29,30]. Their sustained activation promotes cytokine production and tubular cell death. Importantly, ES treatment markedly suppressed the phosphorylation of both ERK1/2 and p38, indicating effective suppression of these stress-responsive kinases. This suppression likely contributes to the downstream reduction in proinflammatory cytokine expression and apoptotic markers observed in ES-treated kidneys, supporting the role of ERK1/2 and p38 as pivotal upstream regulators in the pathophysiology of CDDP-induced AKI. In addition to MAPKs, ES significantly attenuated ER stress in CDDP-treated kidneys. CDDP toxicity is linked to an accumulation of misfolded proteins and activation of the UPR in renal tubules [7,8]. When the adaptive UPR is overwhelmed, it shifts to pro-death signaling largely mediated by the transcription factor CHOP, leading to apoptosis of stressed tubular cells [38,39]. Consistent with this, our CDDP-challenged mice showed upregulation of ER stress markers and elevated levels of CHOP and its upstream activators. Importantly, ES treatment blunted the induction of ER stress responses, as reflected by reduced mRNA levels of UPR-related genes and decreased protein expression of CHOP, p-PERK, and ATF6. By alleviating ER stress and preventing CHOP activation, ES likely inhibited a key pro-apoptotic mechanism involved in CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity. Overall, the ability of ES to inhibit both MAPK and ER stress signaling underscores its broad cytoprotective action, enabling renal cells to withstand the otherwise lethal insult induced by CDDP.

Crucially, our study provides new evidence that ES can counteract ferroptosis, a recently recognized type of regulated necrotic cell death involved in CDDP-induced AKI. Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent process characterized by intense lipid peroxidation and depletion of key antioxidants, resulting in catastrophic membrane damage [40]. Mounting evidence indicates that ferroptosis plays a key role in CDDP-induced renal injury [9]. In the CDDP-alone group, we observed that renal tissues exhibited multiple hallmarks of ferroptosis, including a significant increase in lipid peroxidation products, a marked decrease in GSH content, elevated expression of pro-ferroptotic mediators like PTGS2, ACSL4, and TFR1, and reduced protein levels of SLC7A11 and GPX4. These molecular changes are consistent with ferroptotic cell death, as CDDP has been reported to induce iron accumulation and suppress the GSH/GPX4 axis in renal tubules [41–43]. Remarkably, ES treatment effectively reversed the ferroptosis-related alterations induced by CDDP. ES-treated mice maintained near-normal GSH levels and showed significantly reduced accumulation of 4-HNE and MDA, indicating attenuation of oxidative lipid damage. Furthermore, ES preserved renal levels of the ferroptosis-protective proteins GPX4 and SLC7A11, while preventing the pathological upregulation of PTGS2, ACSL4, and TFR1 observed in the CDDP group. The restoration of the GPX4-GSH antioxidant system and the reduction of iron uptake through TFR1 downregulation strongly suggest that ES inhibited the ferroptotic pathway of cell death. This anti-ferroptotic effect is likely a consequence of ES’s antioxidant capacity and its ability to support endogenous defenses. Targeting ferroptosis has emerged as a critical therapeutic strategy in AKI, especially given that conventional treatments largely overlook non-apoptotic cell death mechanisms [44,45]. The ability of ES to simultaneously restore redox balance and modulate iron metabolism positions it as a unique intervention among antioxidant agents.

Previous studies have demonstrated the renoprotective activity of ES in lupus nephritis [21], hyperglycemia-induced oxidative renal injury [22], and ischemic AKI with diabetic comorbidity [23]. However, its efficacy against chemotherapy-associated nephrotoxicity has not been investigated. CDDP-induced AKI involves common mechanisms such as oxidative stress, ER stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction, along with distinctive features including transporter-mediated tubular accumulation, DNA damage–p53 signaling, and ferroptosis [2,4,5,7,9]. In this clinically relevant model, we show for the first time that ES improves renal function and histology while concurrently attenuating multiple injury pathways, thereby expanding its therapeutic scope and highlighting its potential in oncology settings where nephrotoxicity limits chemotherapy efficacy.

From a translational perspective, it will be important to optimize the timing and duration of ES administration and to ensure compatibility with standard supportive care. ES may also be applicable to other drug-induced nephrotoxicities and in high-risk groups such as elderly patients or those with baseline renal impairment [46]. Before clinical application, however, it will be necessary to confirm that ES does not compromise the anticancer activity of CDDP in tumor-bearing models and to perform comprehensive safety evaluations, including chronic toxicity and genotoxicity studies. Notably, several studies have also reported anticancer properties of ES itself [12], although its interactions with CDDP require further investigation.

Pharmacokinetic data indicate that ES has moderate oral absorption but undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism, limiting systemic exposure [47,48]. Strategies such as nanoparticle delivery, prodrug design, or co-administration with bioavailability enhancers may improve its clinical utility [49–51]. The dose selected in our study (40 mg/kg/day) was supported by prior efficacy and safety data [18–21] and corresponds to a HED of approximately 3.2 mg/kg using allosteric scaling [28]. ES was well tolerated at this dose, consistent with previous toxicology studies reporting no hepatic, hematologic, or renal toxicity at higher exposures [52]. In contrast, other nephroprotective candidates, including bardoxolone methyl and luteolin, have been associated with adverse effects such as cardiovascular toxicities [53,54], underscoring the potential safety advantage of ES.

This study has several limitations. First, only a single ES dose was tested, and dose–response analyses will be required to establish the optimal therapeutic range. Second, we focused exclusively on the acute phase of CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity (72 h post-treatment), leaving unanswered whether ES confers sustained protection against chronic outcomes such as fibrosis or progressive renal decline. Third, a positive control group was not included, as the primary objective was to investigate the mechanistic effects of ES rather than benchmark its efficacy against established nephroprotective agents. Nevertheless, future studies incorporating positive controls will be important to contextualize the protective capacity of ES. Fourth, our conclusion regarding ferroptosis modulation was based on molecular markers, including decreased TFR1 and increased GPX4/SLC7A11 expression, together with reduced lipid peroxidation. While these are widely accepted regulators of ferroptotic cell death, we did not directly measure renal iron content or ferritin levels, which would have provided complementary evidence. Incorporating such analyses will be an important focus of future studies to more comprehensively validate the role of ferroptosis in CDDP-induced renal injury. Fifth, we did not investigate whether ES directly modulates ferroptosis-related transcriptional programs or upstream regulatory pathways. Given the increasing recognition of ferroptosis as a central driver of CDDP-induced renal injury [44], further mechanistic studies are warranted. Finally, although our data suggest that ES modulates signaling pathways implicated in CDDP-induced renal injury, interventional studies using genetic or pharmacological tools were not conducted to confirm its molecular targets or pathway-specific effects. Future studies addressing these gaps will be essential to fully elucidate the mechanistic basis of ES action.

Our results demonstrate that ES significantly protects against CDDP-induced AKI by improving renal function and preserving tubular structure. ES attenuates key pathogenic mechanisms, including inflammation, oxidative stress, MAPK and ER stress signaling, and ferroptosis. These effects collectively reduce tubular cell apoptosis and histological damage in CDDP-challenged kidneys. Our findings identify ES as a promising therapeutic candidate for preventing CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity and warrant further translational investigation.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by research grants from Daegu Catholic University in 2024 (No. 20245001).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Jung-Yeon Kim, Min Hui Park, and Jaechan Leem; formal analysis, Jung-Yeon Kim and Min Hui Park; investigation, Jung-Yeon Kim, Min Hui Park, and Kiryeong Kim; writing—original draft preparation, Jung-Yeon Kim and Min Hui Park; writing—review and editing, Jaechan Leem; funding acquisition, Jaechan Leem. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Daegu Catholic University Medical Center (approval number: DCIAFCR-240102-35-Y) and were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th edition, National Research Council, USA).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviation

| 4-HNE | 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal |

| ACSL4 | Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 |

| AKI | Acute kidney injury |

| ATF4 | Activating transcription factor 4 |

| ATF6 | Activating transcription factor 6 |

| BUN | Blood urea nitrogen |

| CDDP | Cisplatin |

| CHOP | C/EBP homologous protein |

| CXCL1 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1 |

| CXCL10 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| ER | Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| ES | Esculetin |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| GPX4 | Glutathione peroxidase 4 |

| GRP78 | Glucose-regulated protein 78 |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| HED | Human-equivalent dose |

| HRP | Horseradish peroxidase |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1β |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IRE1α | Inositol-requiring enzyme 1α |

| KIM-1 | Kidney injury molecule-1 |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| NGAL | Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin |

| PAS | Periodic acid-Schiff |

| PERK | Protein kinase R–like endoplasmic reticulum kinase |

| PTGS2 | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 |

| qPCR | Quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SLC7A11 | Solute carrier family 7 member 11 |

| TFR1 | Transferrin receptor protein 1 |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| TUNEL | Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling |

| UPR | Unfolded protein response |

| VCAM-1 | Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 |

References

1. Dasari S, Tchounwou PB. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: molecular mechanisms of action. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;740(Suppl. A):364–78. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.07.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Miller RP, Tadagavadi RK, Ramesh G, Reeves WB. Mechanisms of cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Toxins. 2010;2(11):2490–518. doi:10.3390/toxins2112490. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Ambe K, Aoki Y, Murashima M, Wachino C, Deki Y, Ieda M, et al. Prediction of cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury using an interpretable machine learning model and electronic medical record information. Clin Transl Sci. 2025;18(1):e70115. doi:10.1111/cts.70115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Tang C, Livingston MJ, Safirstein R, Dong Z. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity: new insights and therapeutic implications. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2023;19(1):53–72. doi:10.1038/s41581-022-00631-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Mapuskar KA, Steinbach EJ, Zaher A, Riley DP, Beardsley RA, Keene JL, et al. Mitochondrial superoxide dismutase in cisplatin-induced kidney injury. Antioxidants. 2021;10(9):1329. doi:10.3390/antiox10091329. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Hasnain SZ. Endoplasmic reticulum and oxidative stress in immunopathology: understanding the crosstalk between cellular stress and inflammation. Clin Transl Immunol. 2018;7(7):e1035. doi:10.1002/cti2.1035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Yan M, Shu S, Guo C, Tang C, Dong Z. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in ischemic and nephrotoxic acute kidney injury. Ann Med. 2018;50(5):381–90. doi:10.1080/07853890.2018.1489142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Shu S, Wang H, Zhu J, Fu Y, Cai J, Chen A, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress contributes to cisplatin-induced chronic kidney disease via the PERK-PKCδ pathway. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022;79(8):452. doi:10.1007/s00018-022-04480-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Li L, Zhang H, Tang J. Pathogenesis mechanism of ferroptosis and pharmacotherapy in kidney diseases: a review. Nephron. 2025;149(9):1–13. doi:10.1159/000545387. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Fang CY, Lou DY, Zhou LQ, Wang JC, Yang B, He QJ, et al. Natural products: potential treatments for cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2021;42(12):1951–69. doi:10.1038/s41401-021-00620-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Ju S, Tan Y, Wang Q, Zhou L, Wang K, Wen C, et al. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of esculin and esculetin (review). Exp Ther Med. 2024;27(6):248. doi:10.3892/etm.2024.12536. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Liu M, Sheng Y, Guo F, Wu J, Huang Y, Yang X, et al. Therapeutic potential of esculetin in various cancer types (review). Oncol Lett. 2024;28(1):305. doi:10.3892/ol.2024.14438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Kim SH, Kang KA, Zhang R, Piao MJ, Ko DO, Wang ZH, et al. Protective effect of esculetin against oxidative stress-induced cell damage via scavenging reactive oxygen species. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2008;29(11):1319–26. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00878.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Lee BC, Lee SY, Lee HJ, Sim GS, Kim JH, Kim JH, et al. Anti-oxidative and photo-protective effects of coumarins Isolated from Fraxinus chinensis. Arch Pharm Res. 2007;30(10):1293–301. doi:10.1007/BF02980270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang Z, Zhang J, Shi R, Xu T, Wang S, Tian J. Esculetin attenuates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury and protects neurons through Nrf2 activation in rats. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2024;57:e13914. doi:10.1590/1414-431X2024e13914. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Zhou G, Zhang W, Wen H, Su Q, Hao Z, Liu J, et al. Esculetin improves murine mastitis induced by streptococcus isolated from bovine mammary glands by inhibiting NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. Microb Pathog. 2023;185(6):106393. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2023.106393. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Chen F, Wang N, Liao J, Jin M, Qu F, Wang C, et al. Esculetin rebalances M1/M2 macrophage polarization to treat sepsis-induced acute lung injury through regulating metabolic reprogramming. J Cell Mol Med. 2024;28(21):e70178. doi:10.1111/jcmm.70178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Chen T, Guo Q, Wang H, Zhang H, Wang C, Zhang P, et al. Effects of esculetin on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced acute lung injury via regulation of RhoA/Rho Kinase/NF-κB pathways in vivo and in vitro. Free Radic Res. 2015;49(12):1459–68. doi:10.3109/10715762.2015.1087643. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Cheng YJ, Tian XL, Zeng YZ, Lan N, Guo LF, Liu KF, et al. Esculetin protects against early sepsis via attenuating inflammation by inhibiting NF-κB and STAT1/STAT3 signaling. Chin J Nat Med. 2021;19(6):432–41. doi:10.1016/S1875-5364(21)60042-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Zhu L, Nang C, Luo F, Pan H, Zhang K, Liu J, et al. Esculetin attenuates lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced neuroinflammatory processes and depressive-like behavior in mice. Physiol Behav. 2016;163:184–92. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.04.051. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang Y, Li Z, Wu H, Wang J, Zhang S. Esculetin alleviates murine lupus nephritis by inhibiting complement activation and enhancing Nrf2 signaling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 2022;288(2):115004. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2022.115004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Prabakaran D, Ashokkumar N. Protective effect of esculetin on hyperglycemia-mediated oxidative damage in the hepatic and renal tissues of experimental diabetic rats. Biochimie. 2013;95(2):366–73. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2012.10.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Dagar N, Habshi T, Shelke V, Jadhav HR, Gaikwad AB. Renoprotective effect of esculetin against ischemic acute kidney injury-diabetic comorbidity. Free Radic Res. 2024;58(2):69–87. doi:10.1080/10715762.2024.2313738. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Huang C, Zou K, Wang Y, Tang K, Wu Y. Esculetin alleviates IL-1β-evoked nucleus pulposus cell death, extracellular matrix remodeling, and inflammation by activating Nrf2/HO-1/NF-kb. ACS Omega. 2023;9(1):817–27. doi:10.1021/acsomega.3c06771. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Jung WK, Park SB, Yu HY, Kim YH, Kim J. Effect of esculetin on tert-butyl hydroperoxide-induced oxidative injury in retinal pigment epithelial cells in vitro. Molecules. 2022;27(24):8970. doi:10.3390/molecules27248970. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Han MH, Park C, Lee DS, Hong SH, Choi IW, Kim GY, et al. Cytoprotective effects of esculetin against oxidative stress are associated with the upregulation of Nrf2-mediated NQO1 expression via the activation of the ERK pathway. Int J Mol Med. 2017;39(2):380–86. doi:10.3892/ijmm.2016.2834. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Perše M, Večerić-Haler Ž. Cisplatin-induced rodent model of kidney injury: characteristics and challenges. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018(1):1462802. doi:10.1155/2018/1462802. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Nair AB, Jacob S. A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J Basic Clin Pharm. 2016;7(2):27–31. doi:10.4103/0976-0105.177703. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Liu B, Zhang L, Yang H, Chen X, Zheng H, Liao X. SIK2 protects against renal tubular injury and the progression of diabetic kidney disease. Transl Res. 2023;253:16–30. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2022.08.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Jo SK, Cho WY, Sung SA, Kim HK, Won NH. MEK inhibitor, U0126, attenuates cisplatin-induced renal injury by decreasing inflammation and apoptosis. Kidney Int. 2005;67(2):458–66. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.67102.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Ramesh G, Reeves WB. p38 MAP kinase inhibition ameliorates cisplatin nephrotoxicity in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289(1):F166–74. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00401.2004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Dewaeles E, Carvalho K, Fellah S, et al. Istradefylline protects from cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity and peripheral neuropathy while preserving cisplatin antitumor effects. J Clin Invest. 2022;132(22):e152924. doi:10.1172/jci152924. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Wei Q, Dong G, Yang T, Megyesi J, Price PM, Dong Z. Activation and involvement of p53 in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293(4):F1282–91. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00230.2007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Kang KP, Park SK, Kim DH, Sung MJ, Jung YJ, Lee AS, et al. Luteolin ameliorates cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury in mice by regulation of p53-dependent renal tubular apoptosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(3):814–22. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq528. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Ju SM, Kang JG, Bae JS, Pae HO, Lyu YS, Jeon BH. The flavonoid apigenin ameliorates cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity through reduction of p53 activation and promotion of PI3K/Akt pathway in human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015(6):186436–9. doi:10.1155/2015/186436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Hong SH, Jeong HK, Han MH, Park C, Choi YH. Esculetin suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory mediators and cytokines by inhibiting nuclear factor-κB translocation in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Mol Med Rep. 2014;10(6):3241–6. doi:10.3892/mmr.2014.2613. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Arany I, Megyesi JK, Kaneto H, Price PM, Safirstein RL. Cisplatin-induced cell death is EGFR/src/ERK signaling dependent in mouse proximal tubule cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;287(3):F543–9. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00112.2004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Noh MR, Kim JI, Han SJ, Lee TJ, Park KM. C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) gene deficiency attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852(9):1895–901. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.06.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Zhang M, Guo Y, Fu H, Hu S, Pan J, Wang Y, et al. Chop deficiency prevents UUO-induced renal fibrosis by attenuating fibrotic signals originated from Hmgb1/TLR4/NFκB/IL-1β signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6(8):e1847. doi:10.1038/cddis.2015.206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Yadav VK, Choudhary N, Gacem A, Verma RK, Abul Hasan M, Tarique Imam M, et al. Deeper insight into ferroptosis: association with Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s disease, and brain tumors and their possible treatment by nanomaterials induced ferroptosis. Redox Rep. 2023;28(1):2269331. doi:10.1080/13510002.2023.2269331. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Kim DH, Choi HI, Park JS, Kim CS, Bae EH, Ma SK, et al. Farnesoid X receptor protects against cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury by regulating the transcription of ferroptosis-related genes. Redox Biol. 2022;54(88):102382. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2022.102382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Lin Q, Li S, Jin H, Cai H, Zhu X, Yang Y, et al. Mitophagy alleviates cisplatin-induced renal tubular epithelial cell ferroptosis through ROS/HO-1/GPX4 axis. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19(4):1192–210. doi:10.7150/ijbs.80775. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Dong XQ, Chu LK, Cao X, Xiong QW, Mao YM, Chen CH, et al. Glutathione metabolism rewiring protects renal tubule cells against cisplatin-induced apoptosis and ferroptosis. Redox Rep. 2023;28(1):2152607. doi:10.1080/13510002.2022.2152607. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Long Z, Luo Y, Yu M, Wang X, Zeng L, Yang K. Targeting ferroptosis: a new therapeutic opportunity for kidney diseases. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1435139. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1435139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Huang J, Zhao Y, Luo X, Luo Y, Ji J, Li J, et al. Dexmedetomidine inhibits ferroptosis and attenuates sepsis-induced acute kidney injury via activating the Nrf2/SLC7A11/FSP1/CoQ10 pathway. Redox Rep. 2024;29(1):2430929. doi:10.1080/13510002.2024.2430929. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Wang X, Bonventre JV, Parrish AR. The aging kidney: increased susceptibility to nephrotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15(9):15358–76. doi:10.3390/ijms150915358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Cai T, Cai B. Pharmacological activities of esculin and esculetin: a review. Medicine. 2023;102(40):e35306. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000035306. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Zhang L, Xie Q, Li X. Esculetin: a review of its pharmacology and pharmacokinetics. Phytother Res. 2022;36(1):279–98. doi:10.1002/ptr.7311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Shi F, Yin W, Adu-Frimpong M, Li X, Xia X, Sun W, et al. In-vitro and in-vivo evaluation and anti-colitis activity of esculetin-loaded nanostructured lipid carrier decorated with DSPE-MPEG2000. J Microencapsul. 2023;40(6):442–55. doi:10.1080/02652048.2023.2215345. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Abet V, Filace F, Recio J, Alvarez-Builla J, Burgos C. Prodrug approach: an overview of recent cases. Eur J Med Chem. 2017;127:810–27. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.10.061. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Peterson B, Weyers M, Steenekamp JH, Steyn JD, Gouws C, Hamman JH. Drug bioavailability enhancing agents of natural origin (Bioenhancers) that modulate drug membrane permeation and pre-systemic metabolism. Pharmaceutics. 2019;11(1):33. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics11010033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Heghes SC, Vostinaru O, Mogosan C, Miere D, Iuga CA, Filip L. Safety profile of nutraceuticals rich in coumarins: an update. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:803338. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.803338. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Chin MP, Reisman SA, Bakris GL, O’Grady M, Linde PG, McCullough PA, et al. Mechanisms contributing to adverse cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and stage 4 chronic kidney disease treated with bardoxolone methyl. Am J Nephrol. 2014;39(6):499–508. doi:10.1159/000362906. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Wan C, Liang Q, Ma Y, Wang Y, Sun L, Lai J, et al. Luteolin: a natural product with multiple mechanisms for atherosclerosis. Front Pharmacol. 2025;16:1503832. doi:10.3389/fphar.2025.1503832. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools