Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Sustainable Removal of Cu2+ and Pb2+ Ions via Adsorption Using Polyvinyl Alcohol/Neem Leaf Extract/Chitosan (From Shrimp Shells) Composite Films

Department of Chemistry, Veer Surendra Sai University of Technology, Burla, 768018, India

* Corresponding Author: Trinath Biswal. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Cellulose and Nanocellulose in Polymer Composites: Sustainable Engineering Approach)

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(3), 811-835. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.067022

Received 23 April 2025; Accepted 11 September 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

The purpose of this research work is to determine the removal efficiency of Cu2+ and Pb2+ ions using polyvinyl alcohol/neem leaf extract/chitosan (PVA/NLE/CS) composite films as adsorbent materials from an aqueous medium, with respect to pH, contact time, and adsorbent dosage. The synthesized composite material was characterized using Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, thermogravimetric analysis-Derivative Thermogravimetry (TGA-DTG), X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and scanning electron microscopy-Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDX). The antibacterial activity and swelling response of the material were studied using suitable methodologies. The FTIR study confirmed the interactions among PVA, chitosan, and neem leaf extract. The TGA data reveal the excellent thermal stability of the developed composite films. The SEM micrograph indicates a homogeneous phase morphology with good compatibility among chitosan, the monomer, and the leaf extract. The antibacterial study revealed that the prepared PVA/NLE/CS films exhibit improved antibacterial activity against bacterial growth. It was found that at pH 6.0, the adsorption capacity for both toxic metal ions is maximum, and decreases with a further rise in pH. At this pH, the adsorption capacity of PVA/NLE/CS films increases with a gradual increase in adsorbent dosage, and at a specific pH, the adsorption capacity for Cu2+ is greater than that for Pb2+. The adsorption efficiency is a function of contact time and was found to be maximal at 180 min. Hence, the developed composite material is effective for the removal of metal ions from wastewater.Keywords

Highlights:

• Neem leaf-based hybrid composite film is developed using a polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) matrix, reinforcing both chitosan and neem leaf powder.

• The synthesized hybrid composite material is highly effective for the removal of Cu2+ and Pb2+ ions from water through adsorption.

• The tendency of removal of metal ions increases with an increase in adsorbent dosage and follows the order Cu2+ > Pb2+.

• The adsorption process can be better explained by the Langmuir adsorption isotherm, than the Freundlich adsorption isotherm and follows pseudo-second-order kinetics.

The industrial and mining wastewater mostly contains a noticeable concentration of potentially toxic metal ions of various kinds, with toxic organic pollutants that not only cause a health hazard impact on human beings but also severely affect the environment [1].

The remediation of toxic metal ions from the polluted water and industrial effluents is a challenge to researchers [2,3]. Copper and lead are two significant heavy metals commonly found in industrial wastewater, and both cause serious health risks to humans. Natural sources include soil erosion and the weathering of copper-bearing rocks, while industrial contributions come from electronics manufacturing, mining operations, metal plating, and the corrosion of brass and copper plumbing materials [4]. While copper is an essential mineral for human health, excessive exposure beyond acceptable limits can lead to various serious health issues, including gastrointestinal, neurological, and cardiovascular disorders, as well as liver damage, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhoea [5,6]. Lead contamination in wastewater primarily results from the corrosion of lead-based plumbing systems, as well as activities such as electroplating, battery production, and metal smelting. The use of lead-contaminated drinking water severely affects multiple body systems, specifically the brain, liver, nervous system, kidney, bones, and teeth. It is specifically toxic to pregnant ladies and young children [7,8]. Various human activities contribute to the release of heavy metals into the environment. These include mining, the use of fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides in agriculture, as well as the discharge of inadequately treated or untreated industrial effluents and sewage water [9–11]. For instance, mercury enters aquatic systems through industrial processes such as coal combustion, chlor-alkali production, gold mining, pharmaceutical manufacturing, and the improper disposal of mercury-containing items like electronic waste and fluorescent bulbs [12,13]. Similarly, cadmium pollution in the environment is largely driven by its use in battery manufacturing, pigments, metal plating, and textile production [14]. Polymer hydrogels are widely employed as efficient adsorbents for heavy metals due to the presence of amino and hydroxyl groups, which enable strong binding interactions with metal ions [15]. Zeolites are also utilized to adsorb heavy metals such as mercury (Hg), cadmium (Cd), and lead (Pb). Activated carbon serves as an effective adsorbent for removing metals like copper (Cu), chromium (Cr), lead (Pb), zinc (Zn), and cadmium (Cd) [16]. Other frequently used adsorbents include carbon-based substances such as graphene and carbon nanotubes, as well as clay materials like montmorillonite (MMT), bentonite, and kaolinite [17,18]. Common bioadsorbents include chitosan, red mud, agricultural residues (e.g., rice husk, sugarcane bagasse, wheat straw), plant biomass, and algal biomass [19]. The application of low-cost, eco-friendly sorbents for eliminating hazardous metals from contaminated water is now a promising global issue. Because of the demand of seafood throughout the world, the volume of shrimp shell waste gradually increases, which on degradation, results negative impact to human beings and the surrounding environment. The dried shrimp shell wastes contain about 40%–50% of chitin, which on deacetylation is converted into chitosan [20]. Chitosan and its composite materials are widely used in various sectors, specifically biomedical, tissue engineering, packaging, cosmetics, wound healing, drug delivery, textile miniaturing, and water treatment. The chitosan-based biomaterials possess the capability of remediating potentially toxic metals from wastewater through adsorption. The superior adsorption capability of chitosan-based materials is due to the presence of some active nitrogen sites in the chitosan molecule [21]. The mechanism and efficiency of adsorption of the biocomposite material depend on physical, bacteriological, and chemical parameters of the groundwater of the study area that include redox potential, pH, cations, anions of inorganic and organic materials, and kinds of other metal ions present. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) is a known synthetic polymer which is non-toxic, water-soluble, biodegradable, and biocompatible. PVA has drawn a lot of attention because of some of its unique properties, including cost-effective, non-toxic, biocompatible, highly durable, chemically stable, controlled drug delivery, and membrane preparations [22]. The large number of hydroxyl groups (-OH) present in PVA serves as the active site for blending the additive materials and facilitates the formation of the composite [23–25]. Kumar et al. in 2019 synthesized a nanocomposites film of chitosan/PVA/ZnO, which is used for the removal of organic dyes [26]. Wang et al. in 2025 developed a hydrogel based on PVA, chitosan and studied its application as flexible sensors [27]. Dewanjee et al. in 2025 developed a PVA/Chitosan based hydrogel reinforcing ZnO and cellulose and studied its biomedical applications [28]. Although numerous studies have been carried out based on PVA/chitosan composites, but the novelty of this research work is that the composite material [PVA/neem leaf extract/chitosan (PVA/NLE/CS)] developed is completely new, and two naturally obtainable materials (chitosan derived from shrimp shell and neem leaf extract) are used as reinforcing materials. The use of shrimp shell waste not only forms a new biomaterial but also reduces the pollution load of the environment [29]. The composite material reinforced with NLE demonstrates excellent antimicrobial properties, enhanced thermal stability, sufficient mechanical strength, and biodegradability [30]. The presence of bioactive compounds in NLE, such as nimbin and azadirachtin, contributes to its improved antimicrobial performance. As a result, the composite effectively inhibits the growth of fungi, bacteria, and other microorganisms, making it more resistant to contamination and spoilage. This makes the biocomposite particularly suitable for packaging applications, especially in food packaging, as it helps extend the shelf life of the packaged products.

Furthermore, an innovative new film was designed using these composite materials, and its efficiency in separating Pb2+ and Cu2+ ions from wastewater was studied by adopting suitable methodology. This study evaluated the impact of specific factors, including adsorbent dosage, pH, and contact time. Additionally, various isotherm models were utilized to compare the experimental results with the theoretical data derived from these models.

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) was purchased from Central Drug House Pvt. Ltd. Double-distilled water was prepared in the laboratory. Shrimp shells are collected from the local market, Burla. Neem leaves are collected from the neem trees of the local area. Copper nitrate and lead nitrate were purchased from Lab India, Bhubaneswar.

2.2 Preparation of Neem Leaf Extracts (NLE)

The collected neem leaves (Azadirachtaindica) were properly cleaned with distilled water and then with ethanol to remove dust particles and other contaminants. The leaves were oven-dried at 45°C for 5–6 h till they became brittle. After that, the dried neem leaves were crushed into fine powdered form with the help of a mechanical grinder. The neem powder was then kept in a muffle furnace for about 3–4 h at 250°C for complete drying. The neem leaves changed into a dark green colour and were utilized as filler in the development of the composite film [31].

2.3 Extraction of Chitosan from Shrimp Shells

The shrimp shells were collected and properly cleaned with pure water three times to eliminate the undesired salts, impurities, and surface stains. Then the shells were broken into small pieces by hand and then completely made dry at 60°C for about 48 h; after that, the dry mass of shrimp shells was sieved with a 30-mesh sieve. Chitosan was extracted from the shrimp shell by carrying out various steps such as demineralization, deproteinization, and deacetylation. The process of demineralization was carried out by the addition of 10 g of dried shrimp shell powder to 100 mL of dilute HCl (2 M) with continuous stirring for three hours at 25°C. The residue formed was washed using distilled water and then properly filtered using Whatman 42 filter paper. Then the residue obtained was added to 100 mL of 2.5 M NaOH for 5 h at 50°C. The protein present in the residue was removed through filtration and cleaned by washing three times with distilled water. After that, the residue was dehydrated twice with ethanol (95%) and dried overnight at 50°C using an air oven to get chitin. Then chitin obtained was subjected to alkaline deacetylation using a 40% (w/v) NaOH solution. Then the chitosan, which is a deacetylated form of chitin, was thoroughly filtered, clearly washed with distilled water, and then made dry to get pure chitosan. Fig. 1 represents the extraction of chitosan from shrimp shells [32]. The synthesis of chitosan from chitin is represented in Scheme 1.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram for Chitosan extraction from shrimp shells

Scheme 1: Deacetylation of chitin to form chitosan

2.4 Preparation of PVA/NLE/CS Composite Films

The solvent casting method was utilized to fabricate the composite film by incorporating NLE into the PVA/CS matrix for reinforcement. In this process, chitosan (0.5 g) was combined with 25 mL of a 2% (v/v) solution of CH3COOH and stirred continuously for about 1 h. Then 1.6 g of PVA and double-distilled (16 mL) water were added to the solution with continuous stirring for about 45 min. After that, both PVA and CS solutions were taken in the reaction vessel with continuous stirring for about 6 h at 60°C until a clear solution. Then 0.1 g of NLE was added to the PVA/CS solution mixture and continuously stirred for approximately eight hours. The solution was placed in a clean, uncontaminated Petri dish and dried at 45°C in a sealed oven to remove the excess solvent. Fig. 2 represents the synthesis pathway of the PVA/NLE/CS composite films [33].

Figure 2: Synthesis process of PVA/NLE/CS composite films

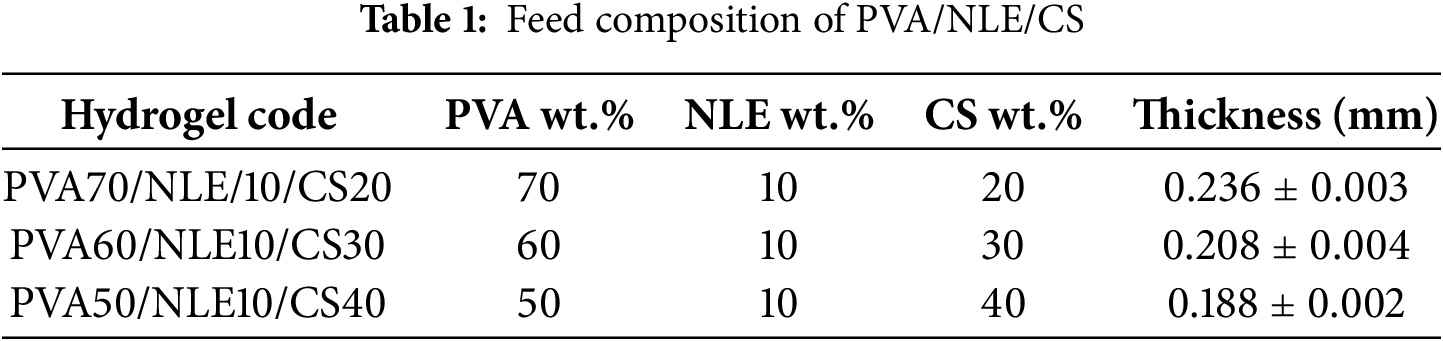

The higher the casting volume of the film-forming solution, the greater the thickness of the composite material after evaporation of the solvent. The higher casting volume increases the probability of homogeneous distribution of various components within the composite material [34]. The rate of drying of the composite material increases with an increase in exposed surface area because of an increase in the rate of evaporation of the solvent. The increase in surface area influences the morphology and increases the microstructure of the composite material. The drying condition depends on various factors such as temperature, humidity, duration of drying, and overall structure of the composite material [35]. The casting volume and thickness of PVA/NLE/CS composite with varying composition ratios are provided in Table 1.

2.5 Fourier Transform Infrared Analysis (FTIR)

The FTIR study of PVA/NLE/CS composite films was conducted using an FTIR spectrophotometer (Nicolet iS50) with a resolution range of 4000–400 cm−1 with 16 scans at 27°C temperature.

2.6 Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

The TGA analysis of the composite films was done using the instrument from Perkin Elmer, USA. An alumina crucible containing 6–10 mg of the sample was heated to 30°C–600°C, maintaining a flow rate of approximately 10 min/°C in an inert nitrogen atmosphere.

2.7 Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The morphological study of the extracted chitosan and composite films (before & after adsorption) was examined using SEM (SEM, Model: JSM-7600F, Jeol Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at a magnification of X500 and an operating voltage of 5 kV.

The XRD diffractograms for extracted CS, NLE, PVA, and composite film material were studied using XRD (Rigaku D/Max-IIA, Tokyo, Japan). The radiation was produced from a Cu Kα source operating at 30 kV and 20 mA, with measurements taken in the 2θ range of 10°–60°, scanning at a speed of 2°/min.

2.9 X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

The mechanism of adsorption of the PVA/NLE/CS composite films was analysed before and after the adsorption of Cu2+ and Pb2+ ions, and was measured through XPS (PHI-5000, Ulvac-Phi, Japan).

The dried mass of the material was converted into the required small pieces (15–20 mg) manually. The swelling properties of the synthesized PVA/NLE/CS composite films were evaluated by immersing the sample in distilled water. Each piece of the sample was immersed in 50 mL of distilled water, maintaining a constant temperature of 30°C. After the specified time, the sample pieces of the material were taken from the container, wiped using tissue paper, and then the sample was weighed using an electronic weighing balance. This process was repeated from 10 to 160 min till the equilibrium swelling point was achieved. Eq. (1) is used to calculate the degree of swelling [36].

where,

In the antibacterial study, the agar plate method was used to know about the in vitro antibacterial efficacy of PVA/NLE/CS films. The antibacterial properties of the films were tested against two distinct bacterial strains, such as Escherichia coli (g-positive) and Staphylococcus aureus (g-negative bacteria). The samples of material were seeded by Petri plates with agar medium, and the dishes were incubated for about five hours at 30°C. The film, having a 0.02 mg/mL concentration of composite material, was made by dissolving it in a solvent (DMSO). The solutions were then injected into 1 mm sterile discs, which were subsequently placed onto bacterial plates that had been inoculated. Streptomycin, a known antibacterial agent, was found for comparison. The plates designed were incubated at the optimum temperature of 37°C for bacterial growth and survival. Antibacterial activity was assessed by observing the inhibition zones nearby the wells, and the diameter of these zones was measured using a pachymeter. The mean and standard error of the calculated experimental data were noted, and all incubations were carried out in duplicate [37].

The batch adsorption experiments were performed by adjusting and optimizing physical parameters, including the contact time, dose response of adsorbent, and pH. In this study, the replicates used in each adsorption experiment are three. The hypothesis testing (t-test) is used to compare between the concentration of the metals before and after adsorption. The capability of adsorption depends on variation in conditions such as adsorption dosage, pH, and time interval. These experimental analyses were carried out under varying conditions, including contact times ranging from 5 to 250 min, pH between 2 and 8, and PVA/NLE/CS with dosages of 0.1–0.6 g/100 mL. A standard solution with a 0.02 g/100 mL concentration was used to maintain the adsorbent dose. Then 0.05 g of the developed PVA/NLE/CS films was submerged in a conical flask containing 100 mL of solution with the addition of 70 mg/L of metal nitrate salt, carefully in the same vessel to quantify the Cu2+ and Pb2+ concentration in the water samples. To attain the adsorption saturation of the metal ion (Cu2+ and Pb2+) of the prepared sample of water, the solution was thoroughly shaken for about 4 h at 25°C, and then kept still for 24 h. The metal ion concentrations were determined by AAS (ICE 3000 Series AA Spectrometer–Thermo Scientific) at a wavelength of 279 nm. Each experiment was conducted in two trials, and the mean value of the two trials was considered the optimum value. The efficiency of metal ion adsorption was estimated using Eq. (2), and the % of metal ion removal was calculated using Eq. (3).

where, q = Adsorption capacity (mg/g) at equilibrium (mg/g)

Ci = Initial concentration of metal ions (mg/L)

Cf = Final concentration of metal ions present in the water sample

V = Volume of the solution prepared water sample in mL

W = Dry weight of the synthesized film.

The buffer solution of different pH was formulated by the following methodology.

A solution with pH 2 was prepared by mixing 0.1 M HCl to a 0.1 M KCl solution. Buffer solutions having pH 3, 4, 5, and 6 were formed by combining 0.1 M citric acid with 0.1 M C6H9Na3O9. For pH 7 and 8, the required buffer solutions were made by adding 0.1 M HCl. 0.1 M Na2HPO4, and 0.1 M NaOH. The prepared buffer solutions were adjusted to 0.1 M, where citric acid serves as a suitable active site for metal ion absorption of the water sample without altering the properties of the water sample [38].

2.13 Competitive Adsorption of Metal Ions on PVA/NLE/CS Composite

The competitive adsorption behaviour of Cu2+ and Pb2+ ions were examined in an aqueous solution where both ions was present at an equal concentration of 70 mg/L. Under identical conditions, the adsorption capacity for each metal ion decreased compared to their individual adsorption scenarios. By comparing the separate adsorption capacities Cu2+ (61.5 mg/g) and Pb2+ (52.08 mg/g), the competitive adsorption capacities increased to 37.1 mg/g for Cu2+ and 31.35 mg/g for Pb2, reflecting a decrease of approximately 65%. This indicates that the presence of one metal ion significantly affects the adsorption behaviour of the other. Overall, the competitive adsorption affinity follows the order: Cu2+ > Pb2+. As shown in Fig. 3, the adsorption capacities of both metal ions under competitive and non-competitive conditions were depicted.

Figure 3: The adsorption capacities of Cu2+ and Pb2+ under competitive and non-competitive conditions

2.14 Effect of Coexisting Water Ions on Adsorption

The presence of excess ions in water leads to competition with the target ions (Cu2+ and Pb2+) for the same adsorption sites on the adsorbent surface. These coexisting ions notably affect the adsorption process by enhancing the adsorption capacity of the target ions. This effect is attributed to factors such as the availability of adsorption sites, a change in surface charge, and alterations in the solvation characteristics of both the adsorbent and the adsorbate.

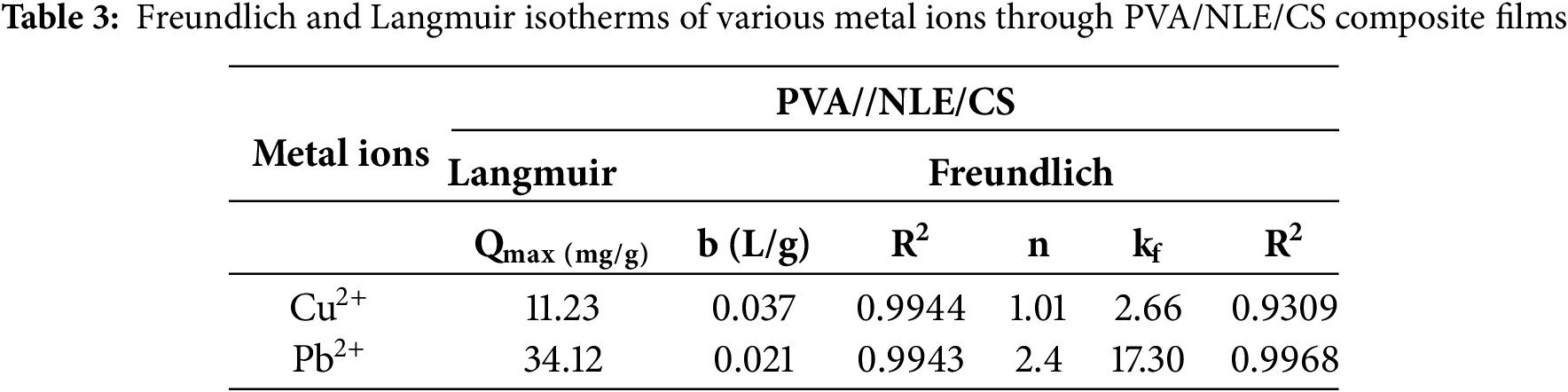

The experiments based on adsorption isotherm were done under similar conditions as the above-mentioned methodology, utilizing the Freundlich and Langmuir isotherm with a constant pH of 6 and maintaining a contact time of 3 h.

3.1 Cross-Linked Network of Hydrogel

Numerous techniques of crosslinking have been adopted for the formulation of composite materials through physical and chemical methods. In the chemical method, the polymer chain molecules are cross-linked by the creation of a covalent linkage between them, whereas in the physical method, the polymer chains are cross-linked by the physical interaction between the polymer molecules. The solubility of the material inhabited because of crosslinking in between the polymer chain molecules. Recently, the formation of hydrogel through physical crosslinking has been focused on, where the cross-linking drastically enhances the interaction between the polymer molecules, which facilitated the formation of hydrogel [39]. The hydrogel formed by physical crosslinking mainly depends on two conditions as follows:

• The intermolecular interaction between the polymer chains is so strong that it can create semi-permanent junctions.

• The structural features of the polymer chain must permit sufficient water to penetrate into the polymeric materials.

Fig. 4 illustrates the FTIR spectrum of the extracted chitosan, pure PVA, NLE, and the composite film. In the FTIR spectrum of chitosan, a distinct broad absorption peak appears at 3396 cm−1, corresponding to the stretching vibrations of -NH2 and -OH groups in the parent chain. Additionally, the spectrum reveals a broad and intense absorption peak at 3396 cm−1, because of the stretching vibrations of these functional groups [40]. The presence of amide groups I and III is confirmed by the peaks appearing at 1556 and 1427 cm−1, respectively. The -CH stretching vibration is responsible for the band at 2922 cm−1, while the -CH symmetrical deformation accounts for the band at 1380 cm−1. The glycosidic linkage observed in chitosan is responsible for the absorption peak at 1022 cm−1. The absorption peak at 1060 cm−1 may be due to the presence of the C–O stretching band. The stretching vibration of the -OH group is indicated by the distinctive strong broad absorbance band at 3432 cm−1 of pure polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), while the symmetric C–H from alkyl groups is represented at 2907 cm−1 [41]. The peaks at 1426 and 1093 cm−1 are related with the bending vibrations of -OH groups and the stretching vibrations of the C–O groups, respectively. The spectra obtained by the FTIR study of NLE show a stretching band at 3444 cm−1. This may be linked with the -OH stretching vibration of the phenolic group. The FTIR peak obtained due to the presence of NLE can be detected at the 2856 cm−1 wavenumber, which is primarily attributed to C–H stretching vibrations. Additionally, the peak at 1636 cm−1 corresponds to the C=O stretching of the -COOH group. The FTIR spectrum of the PVA/NLE/CS composite was established due to the shifting of the absorption peaks. From the FTIR spectrum of the PVA/NLE/CS composite, a peak was identified at 3340 cm−1 (decreased compared to the individual components). This indicates the reduction of –NH2 groups after the creation of the required composite material (PVA/NLE/CS). The –COOMe group of azadirachtin present in NLE binds with the -NH2 groups in chitosan, and this interaction results in the formation of the –NH-CO- bond. A broad and diffuse peak is observed due to the stretching vibration of methylene (-CH2) present in PVA, which is slightly lowered to 2866 cm−1, perhaps because of stretching vibrations caused by the -C–H bond present in the –CH3 group. A characteristic peak is recognized at 1552 cm−1, owing to the existence of an amine group in the chitosan molecules of the developed composite film. The peak obtained at 1728 cm−1 is due to the stretching vibration of the C=O group in the sample, which confirms the presence of NLE in the composite material. Additionally, a new peak is found at 1027 cm−1 (lower frequency), which may be due to the stretching vibration produced by the -C–O bond present in the chitosan and the acetyl group of PVA. This may result from a strong interaction between CS, NLE, and PVA.

Figure 4: FTIR spectra of PVA, CS, NLE and PVA/NLE/CS composite film

3.3 Thermogravimetric Analysis

The thermal degradation of the extracted chitosan and the synthesized composite film is illustrated in Fig. 5a,b. The TGA analysis of the extracted CS shows two stages of degradation. The first stage is called the weight loss zone, that appears between 50–180°C temperature range, which may be due to the moisture evaporation. The second stage of decomposition was identified between 180°C–490°C temperature ranges, resulting from the breakdown of glycosidic linkages. And the elimination of volatile compounds, also known as the products of combustion [42]. The PVA/NLE/CS composite film exhibits three-stage decomposition. In the first stage, weight loss was observed up to 150°C, which results from the loss of moisture. The second stage, which involves major weight loss that appears within a temperature range of 180°C–350°C, is associated with the deacetylation of chitosan, the degradation of the PVA backbone chain, and the degradation of the hemicellulose and cellulose constituents of NLE. The third and final stage of weight reduction occurs within the temperature range of 350°C–600°C, representing the breakdown of lignin components and the pyrogenic decomposition of unstable residues produced in the second stage, which continues throughout the entire temperature range. The DTG thermograms of the extracted CS and PVA/NLE/CS composite film show the maximum degradation, with the highest degradation occurring at 238°C and 251°C, respectively.

Figure 5: (a)TGA plot of CS and PVA/NLE/CS, (b) DTG plot of CS and PVA/NLE/CS composite film

The morphological structure and major elemental analysis of the extracted chitosan and PVA/NLE/CS composite film, before and after adsorption of Pb (II) and Cu (II) ions, were determined using SEM–EDX spectral analysis. The SEM images of chitosan illustrated in Fig. 6a indicate that the particles were scattered with a non-homogeneous distribution and porous cavities, exhibiting rough and uneven shapes and sizes. The elemental analysis of the extracted chitosan indicates the presence of C, O, and N, each with different intensities, that indicates a minimal quantity of protein remnants in the samples. The ‘N’ value is attributed to the amine (–NH2) group of chitosan. The morphological appearance of the film (Fig. 6b) shows roughness, irregularity, and unevenness of the surfaces of the film. Hence, the surface of the film appears heterogeneous, containing numerous cavities with an elliptical shape. This may enhance the aggregation of metal ions on the surface of the film. The higher percentage of swelling is due to the presence of these cavities, which are responsible for the hydrophilic nature of the synthesized film of composite material. The EDX analysis of the composite film identifies the elements C, N, and O along with trace amounts of Mg, P, S, K, and Ca, confirming the presence of NLE. After adsorption, the cavities are covered by novel particles (shining), which were not observed in the adsorbent prior to the loading of metals. This may be due to the adsorbate ions. The SEM image of the synthesized material distinctly shows the distribution of metal ions across the surface of the composite adsorbent. This occurs as a result of the development of a single layer of metal ions on the adsorbent surface. From the EDX analysis of these films after adsorption (Fig. 6c,d) of Cu2+ and Pb2+ ions under non-competitive conditions, it was observed that the elemental components detected in the composite film include C, O, N, Mg, P, S, K, Ca, Cu(II), and Pb(II), which indicate its phase purity and the increasing content of copper and lead. The EDX spectra clearly showed the characteristic peaks corresponding to the presence of metal ions, confirming their adsorption capability.

Figure 6: SEM-EDX of (a) extracted chitosan, (b) PVA/NLE/CS composite film before adsorption, (c) PVA/NLE/CS after Cu(II) adsorption, and (d) PVA/NLE/CS after Pb(II) ions adsorption

Fig. 7 highlights the XRD peaks of the extracted CS, PVA, NLE, and PVA/NLE/CS films. The XRD diffractogram of CS indicates major peaks at 2θ = 10.2° and 19.8°, which are attributed to its hydrated crystalline structure [43]. The XRD analysis of PVA evidenced a peak at 2θ = 19.2°, which may be due to the semi-crystalline structural aspects of PVA [26]. This occurs because strong hydrogen bonds are formed due to the hydroxyl groups present on the parent chain of the PVA moleculee. The amorphous phases in the PVA structure are suggested by the peak at 2θ = 40.2°. The XRD pattern of NLE showed 2θ peaks at 11°, 17°, 25°, 33°, 36°, and 45°. The NLE structure is crystalline in nature because of the presence of minerals based on metals, including Ca, Na, Mg, Fe, Cr, Cu, and Zn. A noticeable change was recorded in the XRD patterns, suggesting a noticeable modification in the PVA/NLE/CS films. The shift in 2θ values to 2θ = 16.2° and 2θ = 24.8° in PVA/NLE/CS, when compared to pure CS, NLE, and PVA, indicates structural changes. A significant decrease in intensity is also observed, which can be associated with the presence of broad amorphous peaks, which decrease and confirms molecular miscibility in the polymer matrix.

Figure 7: XRD pattern of Chitosan, NLE, PVA and PVA/NLE/CS composite films

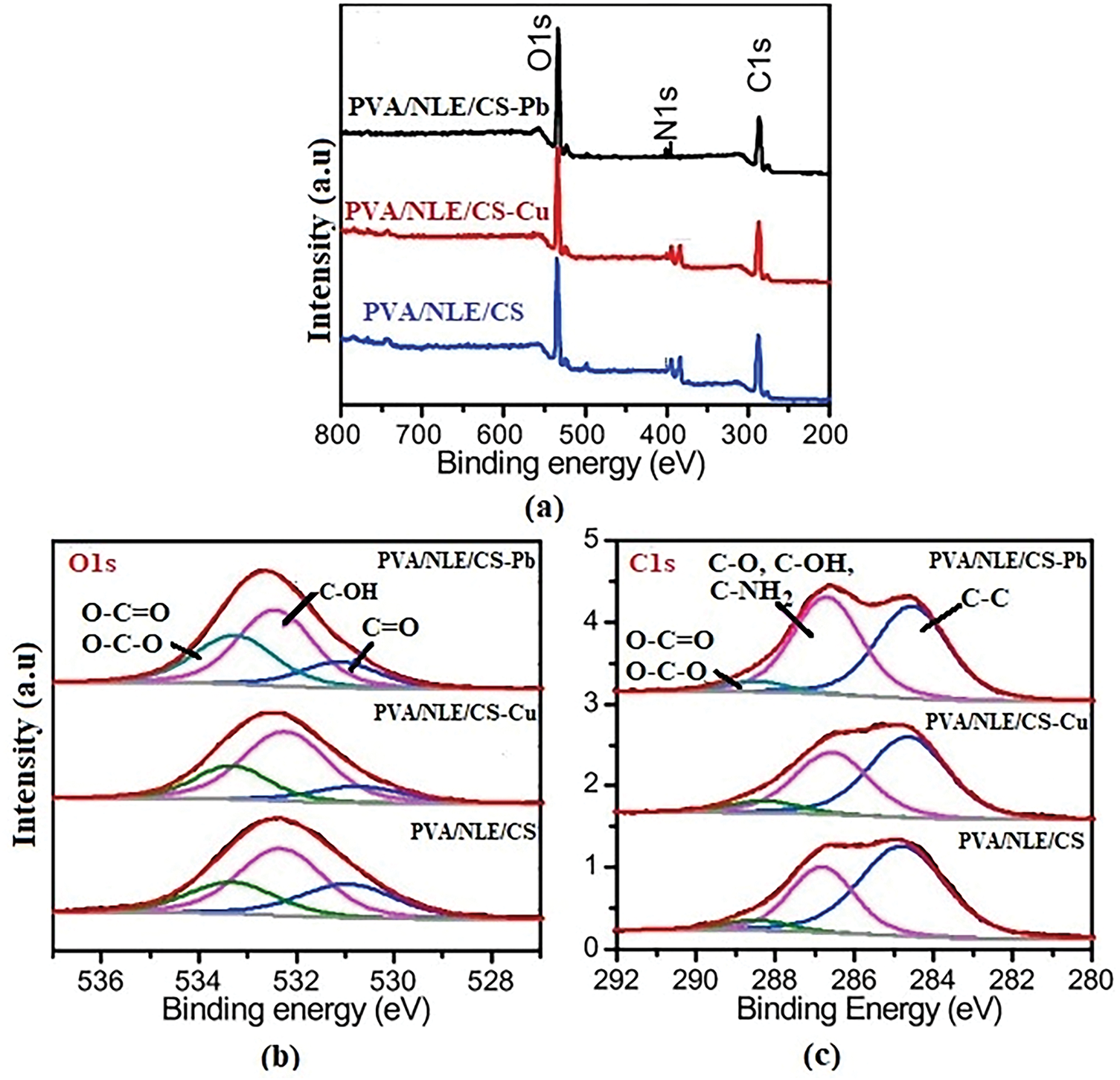

XPS provides the information regarding the chemical state and elemental composition with interaction between the functional groups of PVA, chitosan, and NLE. It confirms the successful adsorption of metals at the surface of the composite material. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was employed to analyze the interactions between the adsorbent and the adsorbate. Prominent peaks are observed at binding energies of 285, 400, and 531 eV, which correspond to C 1s, N 1s, and O 1s, respectively. As shown in the inset of Fig. 8a, the unmodified sample contains 69.57% carbon, 6.82% nitrogen, and 21.86% oxygen. Similarly, the high-resolution O1s spectrum (Fig. 8b) was divided into three peaks cantered at 533.4 eV (O–C=O and O–C–O), 531.9 eV (C–OH), and 531.2 eV (C=O). The high-resolution C1s spectrum (Fig. 8c) was categorized into three distinct peaks at 286.4 eV (representing C–O, C–OH, and C–NH2), 288.9 eV (corresponding to O–C=O and O–C–O), and 284.8 eV (associated with C–C/C=C/C–H). Due to adsorption, the oxygen content increases to 26.04%, while the carbon content decreased to 65.85%, indicating surface oxidation and the formation of oxygen-containing functional groups like hydroxyl and carboxyl. These groups enhance both adsorption capacity and catalytic performance. The nitrogen content remains stable at approximately 6.8%, suggesting the nitrogen functionalities are structurally stable and contribute to reactivity and adsorption. The integration of oxygen-rich groups facilitates electron transfer, which is essential for effective adsorption and degradation. Binding energy shifts observed after metal ion adsorption indicating that Cu2+ and Pb2+ ions attach to the hydrogel and composite surfaces. The slight shifts in peak positions further suggest electrostatic interactions between the metal ions in solution and the oxygen atoms in the composite [44].

Figure 8: XPS spectra of PVA/NLE/CS (a) survey spectrum before and after adsorption, (b) O 1 s spectrum, (c) C 1 s spectrum

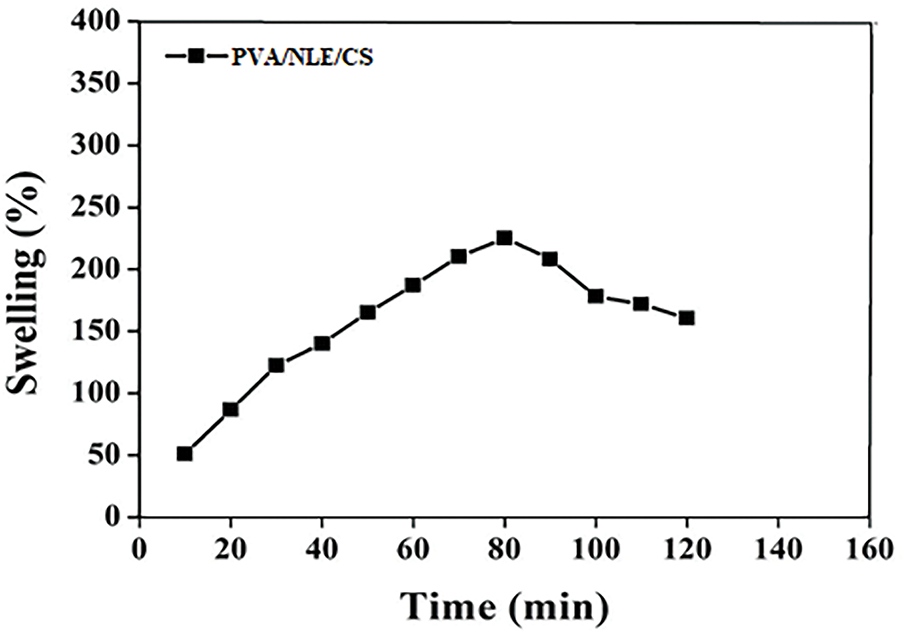

The synthesized composite material exhibits significant swelling behaviour due to the hydrophilic properties of PVA and the existence of numerous pores and voids on the surface layer, which result from the cross-linking of polymer chains of the synthesized composite material [45]. The swelling behaviour of the developed PVA/NLE/CS composite film was studied over different time intervals using distilled water. The hydrophobicity of the material appears due to the -OH groups present in carboxylic acids, which possess an exceptional capacity to form hydrogen bonds on interaction with molecules of water. This is the cause of increase in the capability of absorbing water. At the time of synthesis of the composite material, the formation of hydrogen bonds between the PVA and chitosan molecules increases the cross-linking; therefore, the penetration of water increases, resulting in the increase in swelling ratio. But after 80 min the NLE decreases the rate of water vapor transmission or film solubility. The decrease in solubility reduces the absorption of water by the composite film over time, resulting in the decrease in swelling ratio [46]. The developed novel composite film material possesses excellent water absorption capability and, therefore can be used successfully for cultivation and gardening in water-scarce or desert areas. Fig. 9 illustrates the swelling capability of the PVA/NLE/CS composite films.

Figure 9: Swelling graph of PVA/NLE/CS composite film

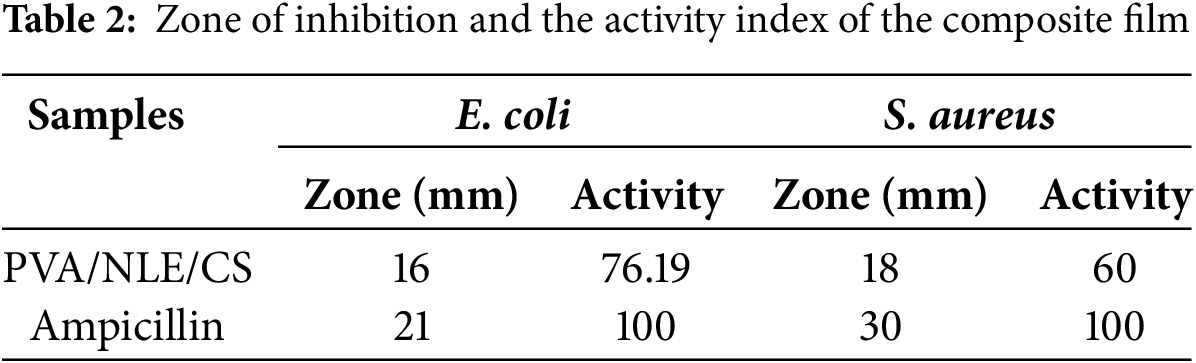

The bacteriological activity of the synthesized biomaterial film for both bacteria (E. coli and S. aureus) has been analyzed using the agar plate method. The results obtained revealed that PVA/NLE/CS possesses potential antibacterial activity against both bacteria. The antibacterial activity of PVA/NLE/CS is perhaps due to the biocidal action of each constituent. The antibacterial activity can be explained due to the presence of positively charged amino groups (-NH2) present in chitosan molecules. The phenolic -OH groups in PVA and NLE are directly linked with the phospholipid cell membrane [47]. This leads to seepage of intracellular constituents and destruction of bacterial cells. The calculated zone of inhibition and the activity index are illustrated in Table 2. Fig. 10 shows the antibacterial activity of PVA/NLE/CS composite films.

Figure 10: PVA/NLE/CS composite films in (a) E. coli bacteriostatic zone (b) S. aureus inhibition zone, (c) PVA/NLE/CS film inhibition zone in E. coli and (d) PVA/NLE/CS film inhibition zone in S. ureus

Fig. 11 illustrates the proposed mechanism for the adsorption of Cu2+ and Pb2+ onto the PVA/NLE/CS composite. The adsorption of these metal ions from aqueous solutions primarily occurs through interactions between the hydroxyl (-OH) and amino (-NH2) functional groups of chitosan present in the composite material. Following the adsorption of Cu2+ and Pb2+, a precipitate forms, and the metal ion concentration within this precipitate reflects the adsorption efficiency. More number of active sites specifically the hydroxyl and amino groups present on the surface of the composite material significantly enhances the adsorption process [48]. The adsorption process is facilitated by the combination of electrostatic attraction, chelation, and ion exchange technique. Due to the protonation and deprotonation of numerous amino groups on the surface of composite, strong binding created between the nitrogen atoms of the amino groups and the metal ions, increasing rate of adsorption. SEM images recorded before and after metal ion adsorption demonstrate the effectiveness of the composite. The microporous structure increases the accessibility of functional groups, providing a large number of active sites that promote the efficient chemisorption of Cu2+ and Pb2+ ions. Although electrostatic repulsion between Cu2+ and Pb2+ cations hinders the adsorption process, but its effect is minimal [49].

Figure 11: Schematic representation of mechanism of adsorption of Cu2+ and Pb2+ ions

The large number of functional groups [carboxyl (-COOH) and hydroxyl (-OH)] present in NLE serves as active binding sites for the removal of metal ions (Cu2+ and Pb2+). The mechanism of adsorption of toxic metals through the composite based on NLE basically involves physical adsorption at the surface because of the formation of a complex due to electrostatic interactions between the targeted metals and functional groups present in the composite material, and facilitates the removal of metals. The various factors that influence the rate of adsorption include the nature of the metals present in the water sample, pH, temperature, and surface of the composite material. The physical adsorption mainly occurs due to electrostatic interactions and van der Waals forces [50].

3.10 Adsorption–Desorption Cycle

NLE is used as a good biosorbent, which functions in adsorption–desorption cycles, and this shows the stability and reusability of the adsorbent material. It functions with long-term adsorption capability and recyclability for the removal of heavy metals and is used in multiple cycles. NLE establishes excellent reusability in adsorption–desorption cycles for removing the contaminants from wastewater and exhibits capacity retention over multiple cycles, but a gradual decrease in efficiency is observed. The capacity retention mainly depends on the kinds of heavy metals present in the water sample and the conditions of the desorption method used. NLE maintains structural stability because of its porous structural network and permits the adsorption of Cu2+ and Pb2+ with high removal efficiency. NLE serves as an excellent biosorbent, reusable in a number of adsorption-desorption cycles, but the leaching is restricted. Since leaching is less, therefore deactivation of the number of active sites during adsorption in each cycle is less, which results in long-term reusability of NLE [51,52].

3.11 Results of Elimination of Metal Ions

The adsorption parameters of Cu2+ and Pb2+ and their corresponding ions can be effectively optimized by considering parameters obtained from experiments, including contact time, pH before and adsorption, the initial concentration of the adsorbent, and the temperature of the experimental conditions. The pathway of adsorption was studied using a suitable methodology.

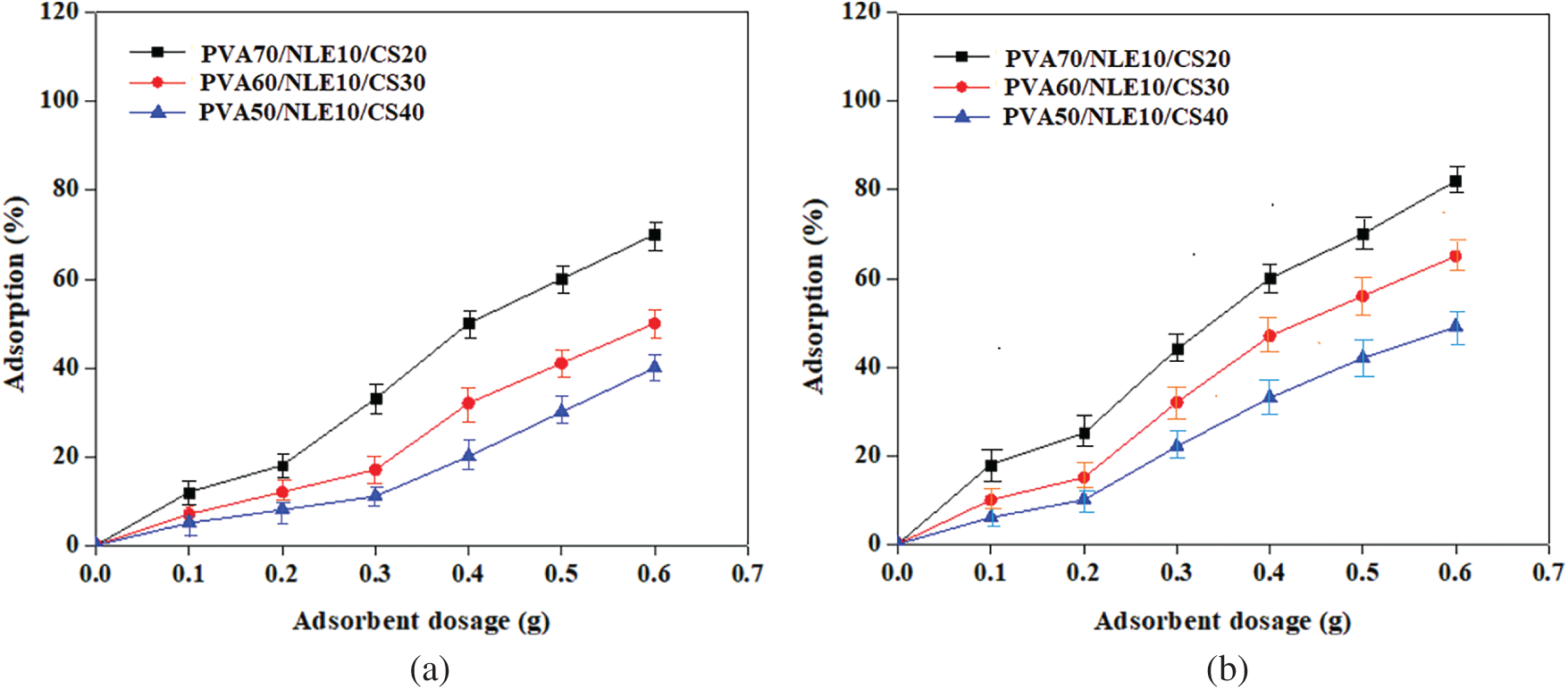

3.11.1 Effect of Adsorbent Dosage

The impact of adsorbent dosage on the adsorption of Cu2+ and Pb2+ ions onto the adsorbent surface at a specific pH (pH 6) and temperature (27°C) was evaluated using varying amounts of PVA/NLE/CS composite films. The range of the adsorbent dosage selected was 0.1–0.6 g, and the percentage of adsorption of the metal ion was noted. This could be attributed to a greater number of binding sites and an expanded surface area of the adsorbent, leading to enhanced ion removal from the solution. Over time, the adsorption rate declined as the adsorbent material reached saturation due to the addition of an optimal amount of adsorbent. The adsorption percentages varied with different adsorbent dosages, demonstrating that the adsorption tendency of PVA/NLE/CS films improves with an increase in adsorbent dosage, following the trend Cu2+ > Pb2+. Fig. 12a,b depicts the effect of varying adsorbent dosage on the adsorption efficiency of the PVA/NLE/CS films for metal ions.

Figure 12: (a) Effect of adsorbent dosage on Cu2+ adsorption. (b) Effect of adsorbent dosage on Pb2+ adsorption

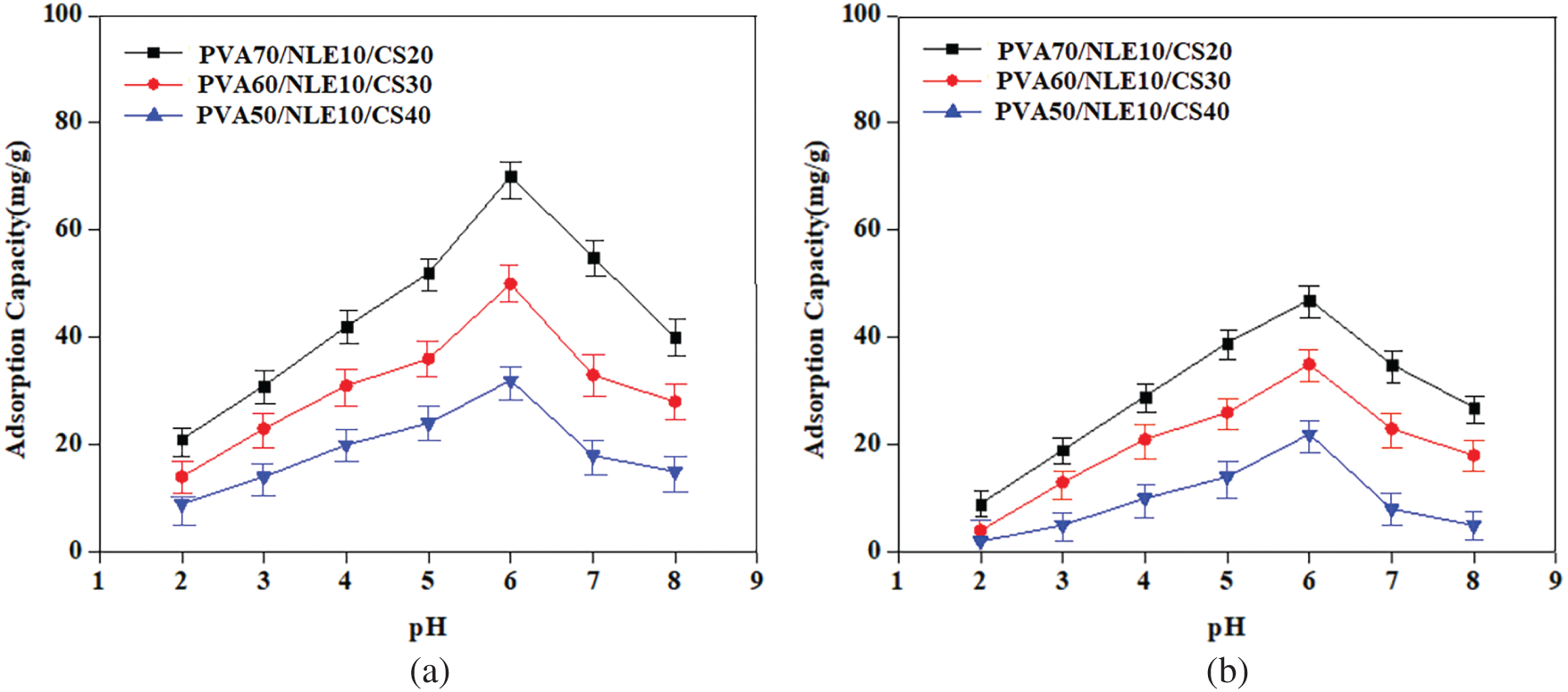

3.11.2 Effect of pH on Adsorption

Each adsorption method is affected by pH, similar to the interaction between various metal ions and adsorbent sites. The results indicate that the adsorption efficiency depends on both pH and temperature. In this study, 0.1 g of the synthesized composite material was introduced into a 70 mg/L solution of toxic metal ions, with the pH maintained between 2 and 8. At lower pH levels, the capability of adsorption of metal ions (Cu2+ and Pb2+) is reduced because the –NH2 amino groups in CS become protonated to –NH3+, which repels other positively charged ions like Cu2+ and Pb2+, thereby lowering the adsorption rate [53]. However, adsorption capacity improves as pH increases within 3 to 6.

The presence of the functional groups such as carboxyl (-COOH) and hydroxyl (-OH) groups present in the composite material act as the primary adsorption sites for metal ions, even in an acidic medium. Under low pH, many active functional groups undergo protonation, with the rate increasing up to pH 6 before decreasing due to competitive adsorption. At pH levels above 6, the adsorbent surface gains more negative charge due to deprotonation, reducing competition with metal ions for binding sites and increases the adsorption capacity. Fig. 13a,b illustrates the impact of pH on the adsorption rate.

Figure 13: (a) Plot of effect of pH on adsorption of Cu2+ ions; (b) Plot of effect of pH on adsorption of Pb2+ ions

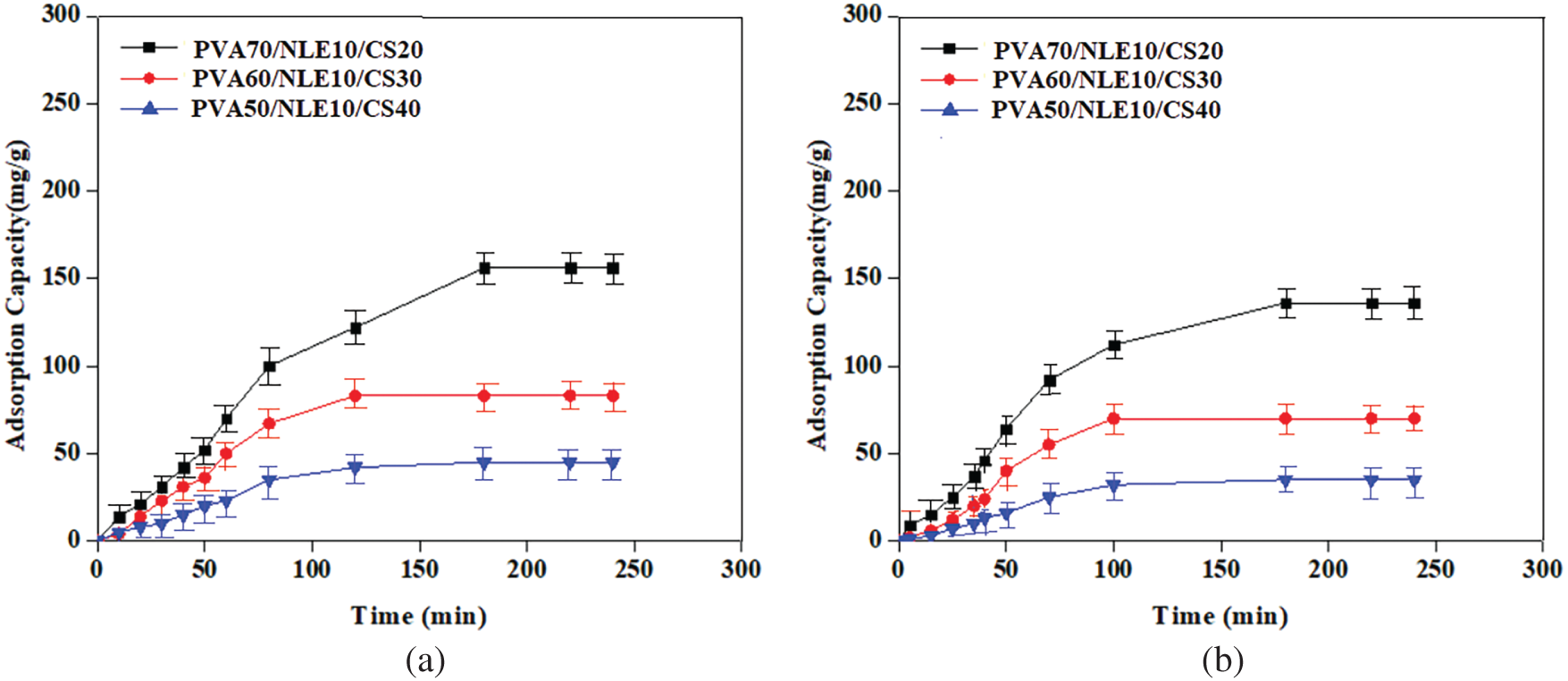

The impact of contact time on the uptake of metal ions depends on the concentration of the ions and the properties of the synthesized composite film. Fig. 14a,b represents the effect of contact time on the adsorption capability of Pb2+ and Cu2+ ions. The experimental results indicate that the adsorption capability progressively improves with increase in contact time and reaches maximum at 180 min. After that, it stabilizes, and equilibrium is attained for both targeted metal ions. The adsorption capability follows the order Cu2+ > Pb2+, and after a certain period of contact, the adsorption efficiency remains constant. The higher adsorption rate at the initial stage is perhaps owing to the formation of more unoccupied active sites on the adsorbent (composite) surface, with time these sites gradually decrease [54]. The adsorption equilibrium might be observed due to Pb2+ and Cu2+ ions occupying the vacant sites on the adsorbent surface, which restricts the mass transfer of metal ions from the aqueous solution to the outer surface of the adsorbent.

Figure 14: (a) Effect of contact time on Cu2+ ions adsorption; (b) Effect of contact time on Pb2+ ions adsorption

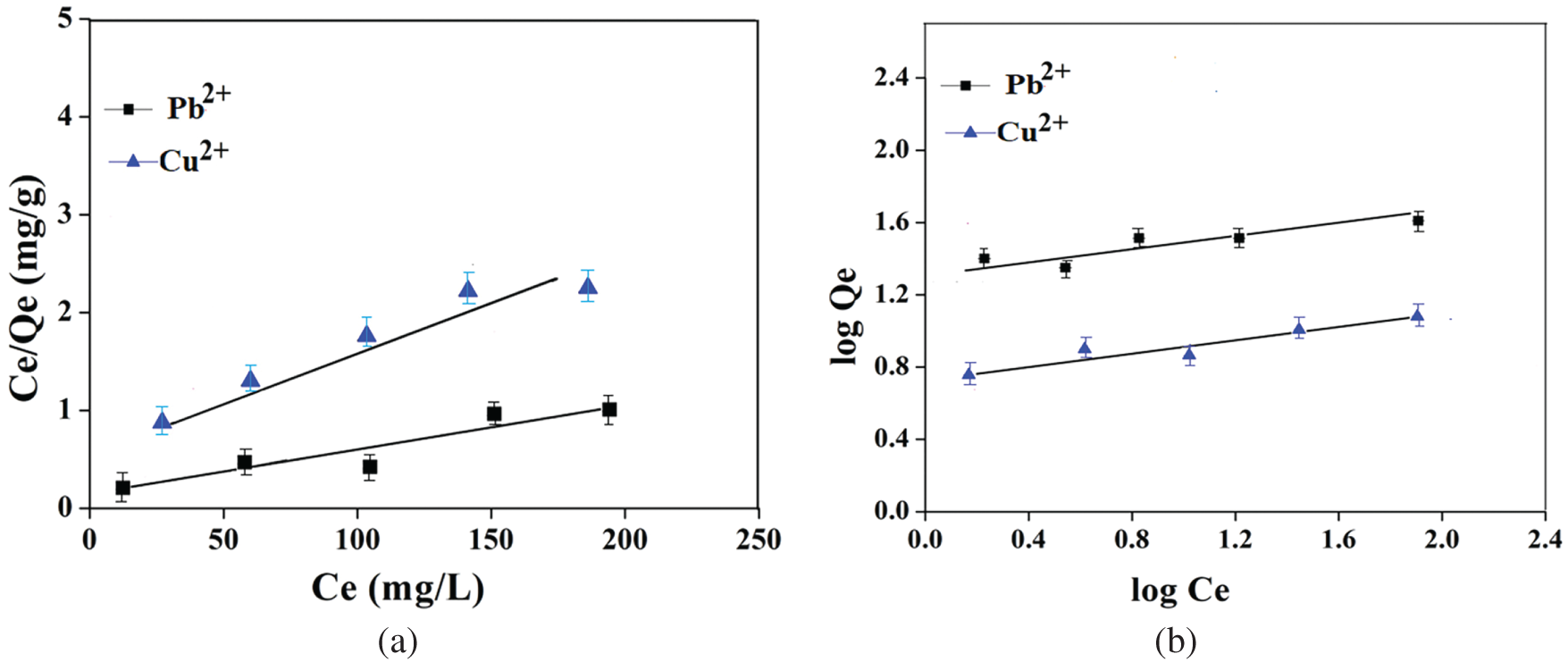

The adsorption isotherm illustrates the interaction of different metal ions attached to the adsorbent material, which is still present in the aqueous solution. This is a crucial parameter required for the process of adsorption. In this research work, the Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm models were both applied for analysing the experimental result and designed a theoretical adsorption system for removing metal ions from the solution. Among these, the Langmuir monolayer adsorption model is better and most extensively applied isotherm and is expressed using Eq. (4).

In the given expression, “b” indicates the adsorption free energy (L/mg), while Qmax represents the highest monolayer adsorption capability according to the Langmuir model, measured in mg/g. Ce indicates the initial concentration (mg/L), and Qe refers to the adsorption capacity (mg/g). The values of “b” and Qmax are measured using the intercept and slope of the Langmuir adsorption plot, where Ce is plotted against Ce/Qe. Furthermore, RL is a crucial parameter in the Langmuir isotherm [55]. It is defined and interpreted using Eq. (5).

C0 (mg/L) represents the concentration of metal ions prior to adsorption, whereas the value of RL reflects the viability of the isotherm. An RL value ranging from 0 to 1 confirms favourable and viable adsorption, whereas RL = 1 shows unfavourable adsorption with linear adsorption behaviour. The plots based on the linear isotherm based on the Langmuir model of PVA/NLE/CS are presented in Fig. 15a. The adsorption ability of Pb2+ and Cu2+ metal ions onto PVA/NLE/CS was closely aligned with the Langmuir equation (RL = 0.9), signifying the creation of a single molecular layer of metal ions on the surface of the adsorbent at saturation stage.

Figure 15: (a) The linear isotherms plot of Langmuir model PVA/NLE/CS. (b) The linear isotherms plot of Freundlich model PVA/NLE/CS

The Freundlich model explains heterogeneous nature of adsorption by considering the various sites for adsorption found in the material (hydrogel) and the diversity of metal ions undergoing adsorption. The heterogeneity factor (1/n) characterizes the behaviour of hydrolysed or free species. The linear state of the Freundlich equation is represented in Eq. (6).

Ce refers to the equilibrium concentration in mg/L, while kf plays an approximate indicator based on capacity (Freundlich isotherm). The parameter ‘n’ denotes the number of functional active sites in the composite material, which is accountable for the adsorption of metal ions [56].

The study revealed that the Freundlich isotherm model had achieved the highest R2 value, indicating a superior fit for the adsorption data. 1/n < 1, indicates favourable and heterogeneous adsorption. Accordingly, the 1/n values demonstrated the favourability of metal ion adsorption onto the surface of the PVA/NLE/CS composite film. This study revealed that Pb2+ exhibited a relatively lower adsorption capacity than Cu2+. The ‘n’ value for each kind of metal ion is found to be greater than one, indicating effective adsorption of metal ions, which is validated by the correlation coefficient (R2), where R2 > 0.99 (Fig. 15b).

Since R2 > 0.99 (Table 3), it demonstrated that both the metal ions are effectively adsorbed by the composite film. This experimental data is compared with the results of the Freundlich and Langmuir isotherms. But from these two models, the Langmuir isotherm kinetic model is more effective as compared to the Freundlich isotherm. It is suggested that the Langmuir isotherm model more accurately predicts the adsorption of Cu2+ and Pb2+ metal ions from solution.

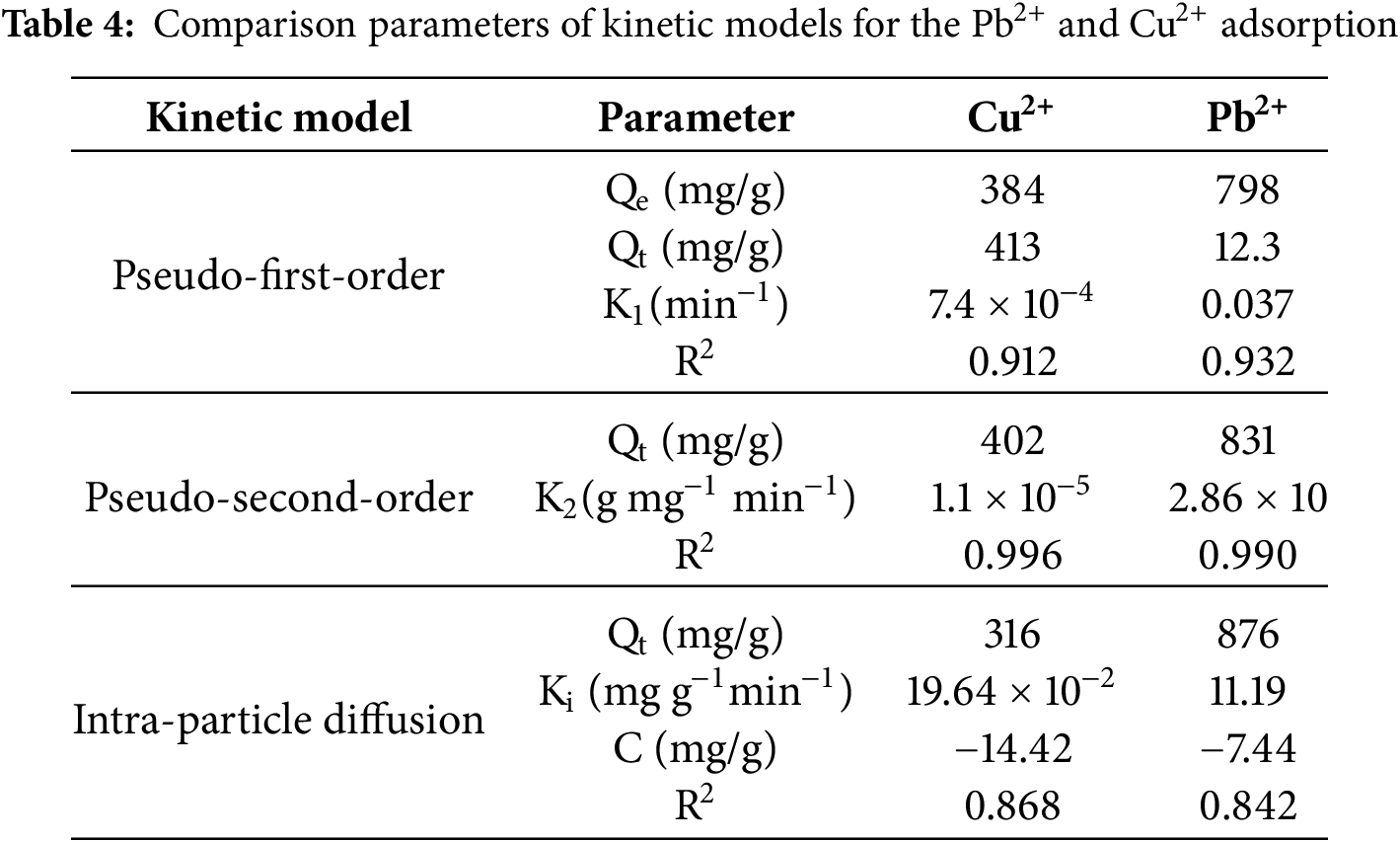

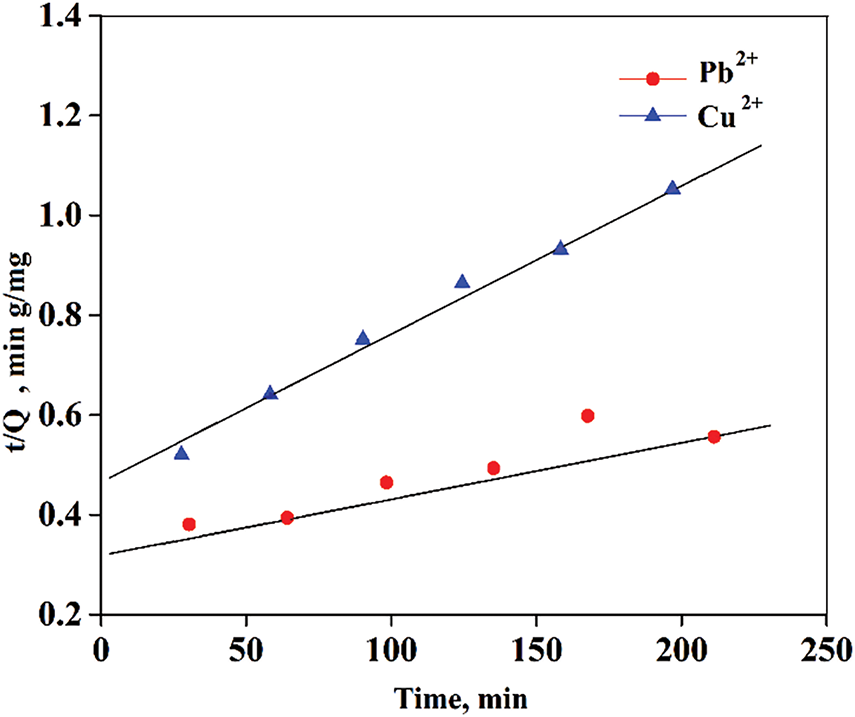

Hence, adsorption kinetics is essential for determining the time required for the uptake of Cu2+ ions on the adsorbent surface and for interpreting the transport mechanism. The adsorption kinetics behaviour of both metal ions was assessed using typical theoretical models, which provide useful information for modelling. The adsorption kinetics of the result was studied based on pseudo-second-order and pseudo-first-order kinetic models. Furthermore, the intra-particle diffusion kinetics model was employed to examine diffusion mechanisms [50–52]. The mathematical formulas for these three kinetic models, i.e., pseudo first-order, pseudo second-order, and intra-particle diffusion kinetics model, are represented in Eqs. (7)–(9), respectively.

Qe and Qt represent the amounts of ions adsorbed onto the adsorbents (mg g−1) at the stage of equilibrium and at a given time in min. For pseudo-first-order adsorption kinetics the rate constant is k1 (min−1), whereas for pseudo-second-order adsorption kinetics, the rate constant is k2 (g mg−1 min−1). The rate constant for intra-particle diffusion adsorption kinetics is represented by ki (mol g−1 min−1/2), while C is a constant expressed in moles per gram (mol/g). Table 4 illustrates the kinetic models based on intra-particle diffusion, pseudo-first-order, and pseudo-second-order adsorption.

The analysis of this model revealed that the pseudo-first-order kinetic model is not appropriate for defining the adsorption of Cu2+ and Pb2+ on the surface of the composite, as evidenced by its low correlation coefficient. In contrast, the pseudo-second-order kinetic model shows comparatively more accuracy of the adsorption kinetics of the specific metal ions (Fig. 16). The adsorption capacity (Qe) predicted by this model closely aligns with the experimentally determined values (Qt). Furthermore, the intra-particle diffusion model exhibits a lower correlation coefficient compared to both the pseudo-first-order kinetic model and pseudo-second-order kinetic models, suggesting that it is not an appropriate model for describing the adsorption process of Pb2+ and Cu2+ onto the surface of the composite.

Figure 16: Kinetic plot of adsorption for Cu2+ and Pb2+ by pseudo-second-order model

This study highlights the development of an innovative PVA/NLE/CS composite films synthesized under optimal conditions using a sustainable, cost-effective solvent casting method. The fabricated composite films were analyzed using FTIR, TGA-DTG, SEM-EDX, and XRD techniques. FTIR analysis confirmed the formation of strong bonds among CS, PVA, and NLE components. Morphological study indicates that the composite possesses numerous active sites, attributed to the presence of hydroxyl (-OH) and amino (-NH2) groups, which are responsible for an increase in the capability of adsorption of Cu2+ and Pb2+ ions. Antibacterial study demonstrated that the composite film creates inhibition zones against both E. coli and S. aureus, bacteria, indicating its potential to prevent bacterial penetration. At pH 6, the adsorption capacity of the composite material increases steadily with higher adsorbent dosage, reaching its peak at 0.6 g. Maximum adsorption efficiency is observed at 180 min. Competitive adsorption studies revealed that the individual adsorption capacities for Cu2+ (61.5 mg/g) and Pb2+ (52.08 mg/g) are higher compared to their capacities under competitive conditions (Cu2+ at 37.1 mg/g mg/g and Pb2+ at 31.35 mg/g). Computational modelling and machine learning technique can assist in tailoring and designing that improves the performance of adsorption and practical application. These findings underscore the strong potential of the composite material for removing toxic metals from contaminated water, which is suitable for wastewater treatment. However, challenges such as material loss during adsorption, limited adsorption capacity, low selectivity, and difficulties in regeneration and reuse remain key limitations for this material.

Acknowledgement: We are highly acknowledged to the Department of Chemistry, VSSUT, Burla for providing support to complete this work.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Deepti Rekha Sahoo: Writing—original draft, Visualization, Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Software, Methodology, Conceptualization, Software. Trinath Biswal: Review & editing, Supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Barakat MA. New trends in removing heavy metals from industrial wastewater. Arab J Chem. 2011;4(4):361–77. doi:10.1016/j.arabjc.2010.07.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Qasem NAA, Mohammed RH, Lawal DU. Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewater: a comprehensive and critical review. npj Clean Water. 2021;4(1):36. doi:10.1038/s41545-021-00127-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Shrestha R, Ban S, Devkota S, Sharma S, Joshi R, Tiwari AP, et al. Technological trends in heavy metals removal from industrial wastewater: a review. J Environ Chem Eng. 2021;9(4):105688. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2021.105688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Northey S, Mohr S, Mudd GM, Weng Z, Giurco D. Modelling future copper ore grade decline based on a detailed assessment of copper resources and mining. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2014;83:190–201. [Google Scholar]

5. Charkiewicz AE. Is copper still safe for us? what do we know and what are the latest literature statements? Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2024;46(8):8441–63. doi:10.3390/cimb46080498. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Stern BR. Essentiality and toxicity in copper health risk assessment: overview, update and regulatory considerations. J Toxicol Environ Health Part A. 2010;73(2–3):114–27. doi:10.1080/15287390903337100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Naranjo VI, Hendricks M, Jones KS. Lead toxicity in children: an unremitting public health problem. Pediatr Neurol. 2020;113(1):51–5. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2020.08.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Wani AL, Ara A, Ahmad Usmani J. Lead toxicity: a review. Interdiscip Toxicol. 2015;8(2):55–64. doi:10.1515/intox-2015-0009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Timothy N, Tagui Williams E. Environmental pollution by heavy metal: an overview. Int J Environ Chem. 2019;3(2):72. doi:10.11648/j.ijec.20190302.14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Alengebawy A, Abdelkhalek ST, Qureshi SR, Wang MQ. Heavy metals and pesticides toxicity in agricultural soil and plants: ecological risks and human health implications. Toxics. 2021;9(3). doi:10.3390/toxics9030042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Daripa A, Malav LC, Yadav DK, Chattaraj S. Metal contamination in water resources due to various anthropogenic activities. In: Metals in water. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2023. p. 111–27. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-95919-3.00022-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Basu M. Impact of mercury and its toxicity on health and environment: a general perspective. In: Mercury toxicity. Singapore: Springer; 2023. p. 95–139. doi:10.1007/978-981-99-7719-2_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kumari K, Chand GB. Effects of mercury: neurological and cellular perspective. In: Mercury toxicity. Singapore: Springer; 2023. p. 141–62. doi:10.1007/978-981-99-7719-2_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Turner A. Cadmium pigments in consumer products and their health risks. Sci Total Environ. 2019;657(12):1409–18. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.096. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Darban Z, Shahabuddin S, Gaur R, Ahmad I, Sridewi N. Hydrogel-based adsorbent material for the effective removal of heavy metals from wastewater: a comprehensive review. Gels. 2022;8(5):263. doi:10.3390/gels8050263. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Qiu L, Suo C, Zhang N, Yuan R, Chen H, Zhou B. Adsorption of heavy metals by activated carbon: effect of natural organic matter and regeneration methods of the adsorbent. Desalination Water Treat. 2022;252:148–66. doi:10.5004/dwt.2022.28160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Kinoti IK, Karanja EM, Nthiga EW, M’Thiruaine CM, Marangu JM. Review of clay-based nanocomposites as adsorbents for the removal of heavy metals. J Chem. 2022;2022(2):7504626. doi:10.1155/2022/7504626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ashiq A, Vithanage M, Sarkar B, Kumar M, Bhatnagar A, Khan E, et al. Carbon-based adsorbents for fluoroquinolone removal from water and wastewater: a critical review. Environ Res. 2021;197:111091. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2021.111091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Gupta VK, Nayak A, Agarwal S. Bioadsorbents for remediation of heavy metals: current status and their future prospects. Environ Eng Res. 2015;20(1):1–18. doi:10.4491/eer.2015.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Radwan MA, Farrag SAA, Abu-Elamayem MM, Ahmed NS. Extraction, characterization, and nematicidal activity of chitin and chitosan derived from shrimp shell wastes. Biol Fertil Soils. 2012;48(4):463–8. doi:10.1007/s00374-011-0632-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Ahmed MJ, Hameed BH, Hummadi EH. Review on recent progress in chitosan/chitin-carbonaceous material composites for the adsorption of water pollutants. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;247:116690. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116690. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Kumar S, Sarita, Nehra M, Dilbaghi N, Tankeshwar K, Kim KH. Recent advances and remaining challenges for polymeric nanocomposites in healthcare applications. Prog Polym Sci. 2018;80(74):1–38. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2018.03.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Lee EJ, Huh BK, Kim SN, Lee JY, Park CG, Mikos AG, et al. Application of materials as medical devices with localized drug delivery capabilities for enhanced wound repair. Prog Mater Sci. 2017;89:392–410. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2017.06.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Elashmawi IS, Menazea AA. Different time’s Nd: YAG laser-irradiated PVA/Ag nanocomposites: structural, optical, and electrical characterization. J Mater Res Technol. 2019;8(2):1944–51. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2019.01.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Silva E, Barreiros L, Segundo MA, Costa Lima SA, Reis S. Cellular interactions of a lipid-based nanocarrier model with human keratinocytes: unravelling transport mechanisms. Acta Biomater. 2017;53(17):439–49. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2017.01.057. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Kumar S, Krishnakumar B, Sobral AJFN, Koh J. Bio-based (chitosan/PVA/ZnO) nanocomposites film: thermally stable and photoluminescence material for removal of organic dye. Carbohydr Polym. 2019;205(3):559–64. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.10.108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Wang T, Xu B, Yu T, Yu Y, Fu J, Wang Y, et al. PVA/chitosan-based multifunctional hydrogels constructed through multi-bonding synergies and their application in flexible sensors. Carbohydr Polym. 2025;350(26):123034. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2024.123034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Dewanjee S, Ahmed H, Tanvir MA, Ali MB, Dipa SA, Al Imran MI. Development of chitosan-based hydrogel containing polyvinyl alcohol, cellulose and ZnO nanoparticles for potential biomedical applications. Dhaka Univ J Sci. 2025;1(1):43–9. doi:10.3329/dujs.v73i1.81284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Topić Popović N, Lorencin V, Strunjak-Perović I, Čož-Rakovac R. Shell waste management and utilization: mitigating organic pollution and enhancing sustainability. Appl Sci. 2023;13(3):623. doi:10.3390/app13010623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Alarifi IM. Fabrication and characterization of neem leaves waste material reinforced composites. Mater Today Proc. 2021;47(1):5946–54. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2021.04.488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Sunthar TP, Marin E, Boschetto F, Zanocco M, Sunahara H, Ramful R, et al. Antibacterial and antifungal properties of composite polyethylene materials reinforced with neem and turmeric. Antibiotics. 2020;9(12):857. doi:10.3390/antibiotics9120857. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Suneeta K, Rath P, Sri HKA. Chitosan from shrimp shell (Crangon crangon) and fish scales (Labeorohitaextraction and characterization. Afr J Biotechnol. 2016;15(24):1258–68. doi:10.5897/ajb2015.15138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ali A, Shahid MA, Hossain MD, Islam MN. Antibacterial bi-layered polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)-chitosan blend nanofibrous mat loaded with Azadirachta indica (neem) extract. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;138(10):13–20. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.07.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Saravana Kumar M, Pruncu CI, Harikrishnan P, Rashia Begum S, Vasumathi M. Experimental investigation of in-homogeneity in particle distribution during the processing of metal matrix composites. Silicon. 2022;14(2):629–41. doi:10.1007/s12633-020-00886-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Romagnoli M, Gualtieri ML, Hanuskova M, Rattazzi A, Polidoro C. Effect of drying method on the specific surface area of hydrated lime: a statistical approach. Powder Technol. 2013;246:504–10. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2013.06.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Sahoo DR, Biswal T. Complex catalyzed synthesis and prediction of properties of poly(acrylonitrile-co-acrylamide)/crab shell powder composites by using artificial neural network. Polym Compos. 2023;44(7):4178–89. doi:10.1002/pc.27389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Sahoo DR, Biswal T. Study of antibacterial and mechanical properties of poly(methyl methacrylate-co-acrylic acid)/hydroxyapatite biocomposite by using artificial neural network approach. SPE Polym. 2024;5(2):169–81. doi:10.1002/pls2.10117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Rani Sethy T, Biswal T, Kumar Sahoo P. An indigenous tool for the adsorption of rare earth metal ions from the spent magnet e-waste: an eco-friendly chitosan biopolymer nanocomposite hydrogel. Sep Purif Technol. 2023;309(2):122935. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2022.122935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Chen Q, Zhu L, Huang L, Chen H, Xu K, Tan Y, et al. Fracture of the physically cross-linked first network in hybrid double network hydrogels. Macromolecules. 2014;47(6):2140–8. doi:10.1021/ma402542r. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Chen G, Mi J, Wu X, Luo C, Li J, Tang Y, et al. Structural features and bioactivities of the chitosan. Int J Biol Macromol. 2011;49(4):543–7. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2011.06.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. El-Hefian EA, Nasef MM, Yahaya AH. The preparation and characterization of chitosan/poly (vinyl alcohol) blended films. J Chem. 2010;7(4):1212–9. doi:10.1155/2010/626235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Ahyat NM, Mohamad F, Ahmad A, Azmi AA. Chitin and chitosan extraction from Portunuspelagicus. Malays J Anal Sci. 2017;21(4):770–77. doi:10.17576/mjas-2017-2104-02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Qin C, Zhou B, Zeng L, Zhang Z, Liu Y, Du Y, et al. The physicochemical properties and antitumor activity of cellulase-treated chitosan. Food Chem. 2004;84(1):107–15. doi:10.1016/S0308-8146(03)00181-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Karim MAH, Hama Aziz KH. Pristine almond-pomace derived biochar as a low-cost and sustainable peroxydisulfate activator for efficient removal of rhodamine B from water. J Water Process Eng. 2025;75(2):108014. doi:10.1016/j.jwpe.2025.108014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Peng F, Jiang Z, Hoek EMV. Tuning the molecular structure, separation performance and interfacial properties of poly(vinyl alcohol)-polysulfone interfacial composite membranes. J Membr Sci. 2011;368(1–2):26–33. doi:10.1016/j.memsci.2010.10.056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Al-Maharma A, Al-Huniti N. Critical review of the parameters affecting the effectiveness of moisture absorption treatments used for natural composites. J Compos Sci. 2019;3(1):27. doi:10.3390/jcs3010027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Vilela PB, Matias CA, Dalalibera A, Becegato VA, Paulino AT. Polyacrylic acid-based and chitosan-based hydrogels for adsorption of cadmium: equilibrium isotherm, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. J Environ Chem Eng. 2019;7(5):103327. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2019.103327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Elbarbary AM, Ghobashy MM. Phosphorylation of chitosan/HEMA interpenetrating polymer network prepared by γ-radiation for metal ions removal from aqueous solutions. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;162:16–27. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.01.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Wang Q, Zheng C, Cui W, He F, Zhang J, Zhang TC, et al. Adsorption of Pb2+ and Cu2+ ions on the CS2-modified alkaline lignin. Chem Eng J. 2020;391:123581. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2019.123581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Kumar N, Jyoti J, Aggarwal N, Kaur A, Patial P, Kaur K, et al. Adsorption of Pb2+ using biosynthesized ZnO nanoparticles derived using Azadirachta indica (neem) leaf extract. Biomass Convers Biorefinery. 2024;14(23):30601–11. doi:10.1007/s13399-024-05419-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Patel PK, Pandey LM, Uppaluri RVS. Cyclic desorption based efficacy of polyvinyl alcohol-chitosan variant resins for multi heavy-metal removal. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;242:124812. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.124812. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Khulbe KC, Matsuura T. Removal of heavy metals and pollutants by membrane adsorption techniques. Appl Water Sci. 2018;8(1):19. doi:10.1007/s13201-018-0661-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Abdul Hameed MM, Al-Aizari FA, Thamer BM. Synthesis of a novel clay/polyacrylic acid-tannic acid hydrogel composite for efficient removal of crystal violet dye with low swelling and high adsorption performance. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2024;684(640–641):133130. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2023.133130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Kong A, Ji Y, Ma H, Song Y, He B, Li J. A novel route for the removal of Cu(II) and Ni(II) ions via homogeneous adsorption by chitosan solution. J Clean Prod. 2018;192(11):801–8. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.04.271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Al-Senani GM, Al-Fawzan FF. Adsorption study of heavy metal ions from aqueous solution by nanoparticle of wild herbs. Egypt J Aquat Res. 2018;44(3):187–94. doi:10.1016/j.ejar.2018.07.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Naseem K, Farooqi ZH, Begum R, Ghufran M, Rehman MZU, Najeeb J, et al. Poly(N-isopropylmethacrylamide-acrylic acid) microgels as adsorbent for removal of toxic dyes from aqueous medium. J Mol Liq. 2018;268:229–38. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2018.07.039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools